The Thai city of Chanthaburi (จันทบุรี) may be small, but it has played an important role in both the history of Thailand and the gem trade. Taking its name from the Sanskrit word for moon ('chan'), this petite town is among the most charming in the Land of Smiles.

Introduction

In ancient times, Chanthaburi had no gems. Suddenly during a dark night, villagers saw a light glittering in the sky and then watched it drop in the area of Khao Ploi Waen. People ran after the light and saw green rays coming out of a hole and there, they found mae ploi (the mother of gems) and started worshipping the rock. When they tried to touch it, however, the mae ploi flew away and following her were louk ploi or baby gems. Thousand or tens of thousands of louk ploi escaped with her and those that could not follow scattered around the area of Chanthaburi. Krissna Chang-Glom, Chanthaburi, 1988

Thailand (Prathet Thai; ประเทศไทย) was known throughout most of its existence as Siam. Located in the center of mainland Southeast Asia, today it shares borders with Burma, Laos, Malaysia and Cambodia. Among the aforementioned countries, Thailand was the only one to escape European colonization. The Thai, who are ethnically related to the Shan of Burma, the Lao of Laos, and the Tai of Vietnam and southern China, established their first kingdom at Sukhothai early in the 13th century. The present capital of Bangkok (Krung Thep; กรุงเทพฯ) was established in 1782, several years after the previous capital at Ayutthaya was sacked by Burmese invaders. Large-scale immigration from China occurred in the late nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries and today most business, including that of gems, is in the hands of Chinese.

Present-day Cambodia (Kampuchea) traces its history back over 2000 years. The great kingdom of Angkor (of Angkor Wat fame) rose in the ninth century and at one time ruled an empire stretching from the Burmese border to the South China Sea. In the 15th century, in decline, it was pressed on each side by Thais and Vietnamese. Eventually, in 1863, the French moved in and added the territory to their Indochina empire. Cambodia achieved independence from French rule in 1953.

Early History of Chanthaburi

The traditional center of gem mining and trading in Thailand and Cambodia is the town of Chanthaburi. Historical accounts put the founding of Chanthaburi by the Chong ('Xong'), a Mon-Khmer tribe, in the 12th century AD. But 2,000 year-old stone tools found in the area suggest humans have long inhabited the region.

King Taksin the Great

Chanthaburi's history is intimately tied to one of Thailand's greatest kings, King Taksin. Taksin was born in 1733 to a Thai mother and Chinese father and was originally called Sin. Entering government service, he was eventually appointed governor (Phraya) of Tak Province. Thus he became known as Phraya Tak Sin (Taksin).

Following the destruction of Thailand's Ayutthaya Kingdom in 1767 by the invading Burmese army, Taksin and his 500-man army occupied Chanthaburi for five months. Legend has it that many of his soldiers were Chinese, so he retreated to the place with the largest Chinese population (Chanthaburi). But even this retreat was made difficult. The governor of Chanthaburi did not welcome him, and thus Taksin and his troops had to fight to subdue both Chanthaburi and Trat. The location of Taksin's camp was at Khai Nern Wong ('camp on a small hill'), just outside Chanthaburi. The fort Taksin occupied at Khai Nern Wong is still standing today, just a few kilometers from the center of town.

British cannon at Noen Wong Fort at Khai Nern Wong, just outside of Chanthaburi. It was here that Taksin marshalled his forces prior to running the Burmese invaders out of Thailand. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

British cannon at Noen Wong Fort at Khai Nern Wong, just outside of Chanthaburi. It was here that Taksin marshalled his forces prior to running the Burmese invaders out of Thailand. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

After subduing Chanthaburi and Trat, he again turned his attention to the Burmese. In 1768, Taksin and his now 5,000-strong army drove the Burmese out of Thai territory and reunified the country. His first capital was at Thonburi, and it was during his 15-year reign that his general, Chao Phraya Chakri, captured the Emerald Buddha in Laos and brought it to Thonburi.

In 1781, there was a rebellion against King Taksin and he was executed in 1782. The method of execution at that time for nobility was to be put inside a silk sack and be beaten to death with a sandalwood club, since royal blood was not allowed to touch the ground. It has long been rumored that someone else was put in the sack and that Taksin escaped to the South for his final years. This appears unlikely as in those days it was common to also kill all of the ruler's heirs so as to remove the possibility of future claims on the throne.

The new Thai king, Chao Phraya Chakri founded the current Chakri Dynasty. In 1784, Rama I made the decision to move the capital to the opposite bank of Chao Phraya river. On March 22, 1784, King Rama I installed the Emerald Buddha at its present location at Wat Phra Kaew. The city he founded is known to Thais as Krung Thep ('City of Angels') and to the outside world as Bangkok. While he was eventually overthrown, King Taksin is remembered fondly by Thais for recapturing Thailand from the Burmese and unifying the country. Indeed, in 1981, the Thai government passed a resolution to honor him as "King Taksin the Great."

|

A rabbit on the moon? Squinting up at the moon, one can discern a variety of patterns and shapes. While Western cultures conjured up a man on the moon, for the Chinese, it was a rabbit. This ancient Chinese belief dates back as far as 2200 years. According to legend, there is a jade rabbit on the moon who constantly pounds herbs for the immortals. The idea of a rabbit on the moon was not something unique to the Chinese. The same belief was found in Buddhist folklore and even halfway across the globe among the Aztecs of Mesoamerica. Still today, we find traces of the moon rabbit in popular culture. The title character of Sailor Moon, whose name is Usagi Tsukino, is actually a Japanese pun on the words "rabbit of the moon." In Thailand's "City of the Moon", the custom is found in the city seal, a rabbit silhouetted against a full moon surrounded by an aura.

I'll never forget the first time I encountered this notion. The year was 1996 and my friends and I were seriously engaged in a struggle to visit Burma's jade mines. Having spent two days slogging through incredible monsoon mud, on the morn of the third day, we resupplied in the Hweka market. Later, while laughing about our "Superdog" socks and "Moon Rabbit" batteries, our Burmese friend remarked that it was a common belief that there is a rabbit on the moon. We never did find out the origin of Superdog. |

The Chanthaburi melting pot

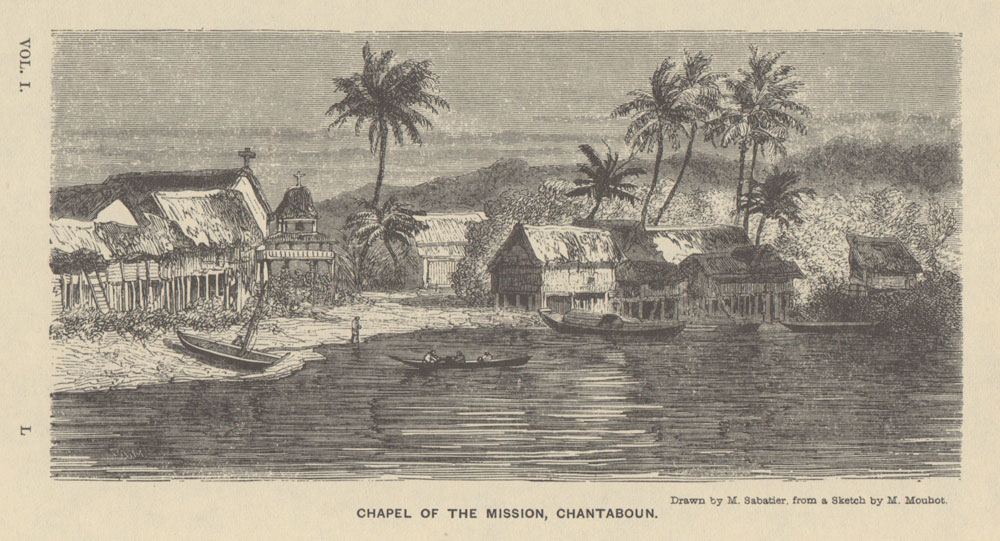

Despite its small size, Chanthaburi is an incredibly cosmopolitan place. In addition to the significant Thai and Chinese populations, Chanthaburi also has a large Vietnamese population. The French-built Catholic Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception was built in 1880 and is said to be the largest Christian church in Thailand. It was built to serve the large number of Vietnamese Catholics who form a significant minority in Chanthaburi.

Yet another major minority in Chanthaburi are the Shan. Known locally as Gula (กุลา; sometimes spelled Kula), they were already familiar with Burma's gems when they passed through the area in the mid-19th century. The Shan quickly recognized the gem potential, which prior to their arrival had been little exploited. Soon these Gula miners and traders had transformed the business and their descendants can be found to this day. Indeed, if one visits Pailin's Phnom Yat temple, the Burmese influence is unmistakable.

French occupation

The French arrived after the Shan. French colonialist troops occupied Chanthaburi for 11 years, starting in 1893, following the Paknam crisis. In 1905, Chanthaburi was returned to Thailand, who in turn was forced to give up ownership of a portion of western Cambodia, including Pailin.

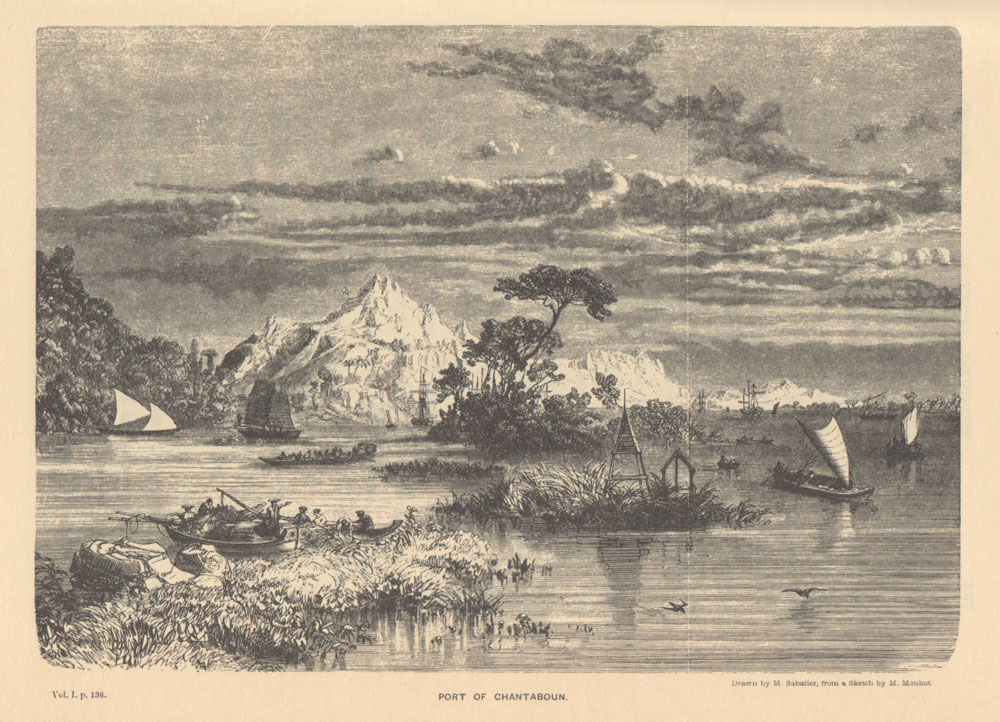

Mid 19th century view of the "Port of Chantaboun." From Mouhot (1864) Travels in the Central Parts of Indo-China (Siam), Cambodia, and Laos, during the Years 1858, 1859, and 1860.

Mid 19th century view of the "Port of Chantaboun." From Mouhot (1864) Travels in the Central Parts of Indo-China (Siam), Cambodia, and Laos, during the Years 1858, 1859, and 1860.

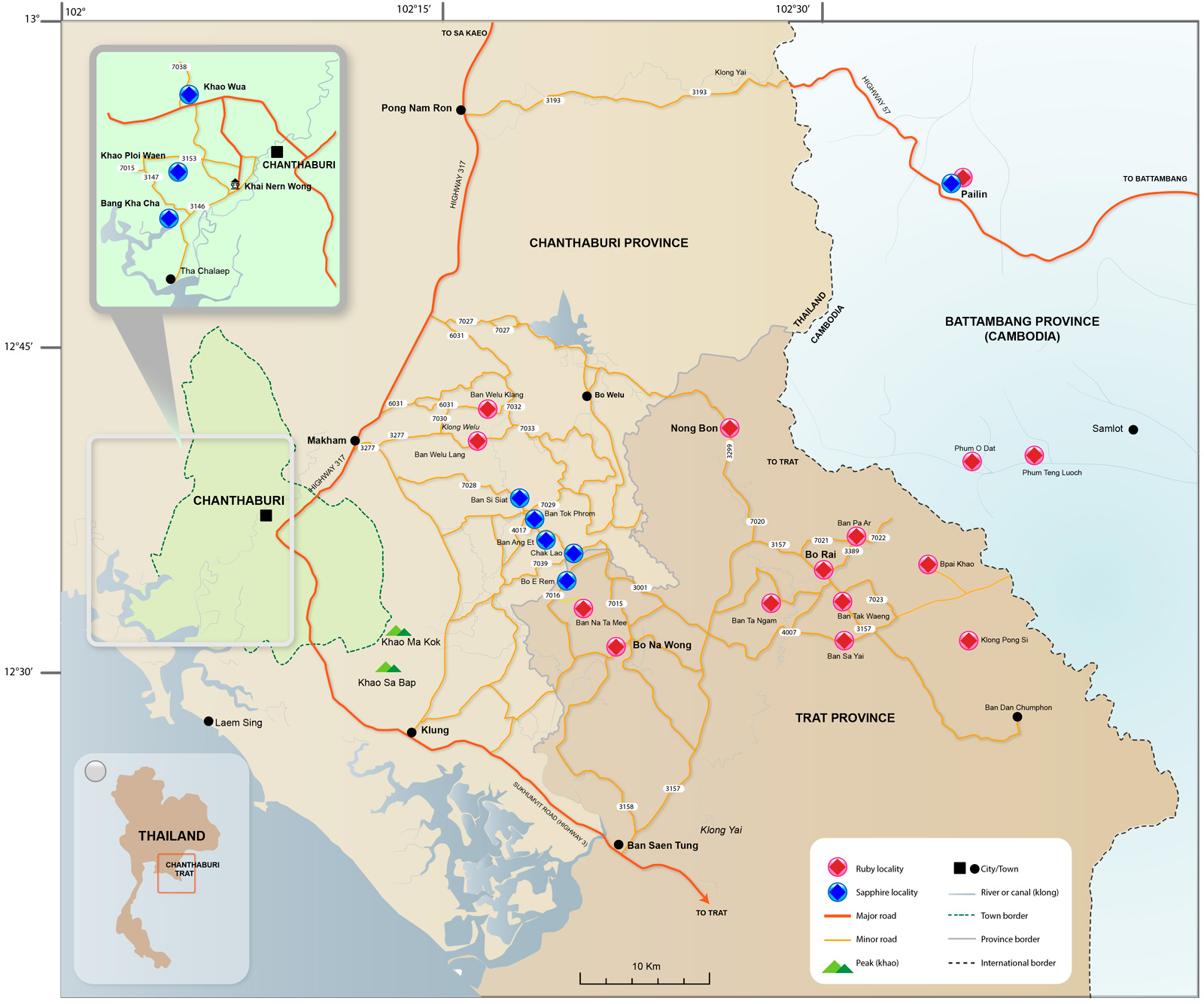

The rubies and sapphires of this region are principally derived from the Thai-Cambodian border region, with mines lying on both sides of the frontier. For this reason, the deposits of both countries will be discussed together. References to the mines in eastern Thailand should also be understood to include those across the border in Cambodia.

Map of Chanthaburi, Trat and western Cambodia, showing the location of the gem mines. Click on the map for a larger image. Map © Richard Hughes.

Map of Chanthaburi, Trat and western Cambodia, showing the location of the gem mines. Click on the map for a larger image. Map © Richard Hughes.

If you have two coins to spend, use the first for food and the other for flowers, for, while the former will keep you alive, the second will give you the reason to live. Chinese proverb

History

The earliest reference to the gems of Siam (Thailand) was that of the Chinese traveler, Ma Huan, in 1408 AD (Phillips, 1887; Gühler, 1947):

A hundred li (twenty miles) to the S.W. of this Kingdom there is a trading place Shang-Shui, which is on the road to Yun-hou-mên, [possibly a canal between Chanthaburi and Trat Provinces in eastern Thailand]. In this place there are five or six hundred foreign families, who sell all kinds of foreign goods; many Hung-ma-sze-kên-ti stones are sold there. This stone is an inferior kind of ruby, bright and clear like the seeds of the pomegranate.

In Manual de Faria’s (1617 to 1640 AD) description of Portuguese Asia it is stated that Siam has “mines of sapphires and rubies” (Ball, 1931). Nicolas Gervaise, writing in 1688, also mentions what may have been an occurrence of sapphire in Siam:

…there are blue stones found in certain parts of the jungle in the uplands. This stone resembles the Lapis which is usually found in gold mines.

Gervaise, however, seemed interested more in gold than precious stones, for this is his only reference to gems (Gervaise, 1688).

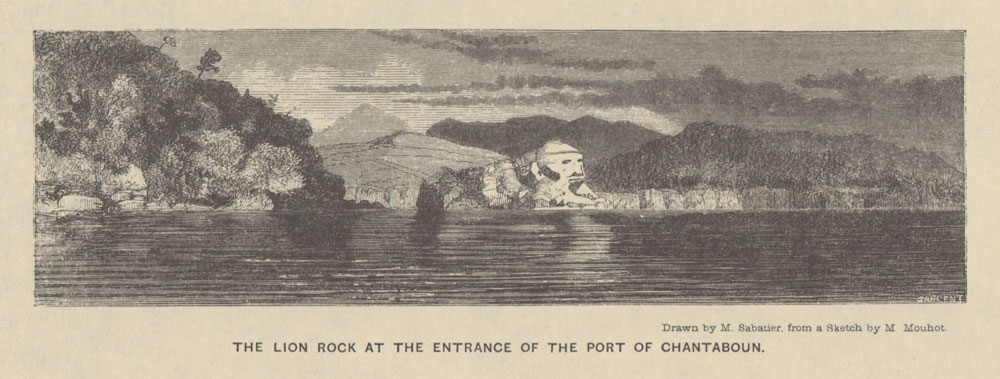

Laem Sing (Lion Rock). From Mouhot (1864) Travels in the Central Parts of Indo-China (Siam), Cambodia, and Laos, during the Years 1858, 1859, and 1860.

Laem Sing (Lion Rock). From Mouhot (1864) Travels in the Central Parts of Indo-China (Siam), Cambodia, and Laos, during the Years 1858, 1859, and 1860.

Laem Sing (Lion Rock) today. Photo © Richard W. Hughes.

Laem Sing (Lion Rock) today. Photo © Richard W. Hughes.

Ulrich Gühler (1947) has given us an authoritative account of the history of gems in Thailand, unfortunately in an obscure Thai journal, beginning with Ma Huan. From the fifteenth century onwards, various travelers to Thailand mention, in passing, that rubies and sapphires are found near Chanthaburi. Also included are the sometimes humorous descriptions of the gems, as well as the local people and their customs. Witness the statements of early French missionaries to Thailand (Cartwright, 1908) from before 1770 on the former Thai province of Laos:

In the province of Laos from whence the kingdom takes its name, there is a deep mine whence rubies and emeralds are extracted. The King possesses an emerald of the size of an ordinary orange.

De la Loubère (1693), French envoy to Siam in 1687, described Thailand as “abounding in mines of rubies and sapphires.” He added that the stones usually found their way into the possession of monks, who were secretive as to the gems’ origin, and who employed them as charms.

Rough gems from Khao Ploi Waen, along with one 12-rayed black star sapphire cabochon. The deep red stones are zircon; the rest are sapphire. Photo © Wimon Manorotkul.

Rough gems from Khao Ploi Waen, along with one 12-rayed black star sapphire cabochon. The deep red stones are zircon; the rest are sapphire. Photo © Wimon Manorotkul.

The nineteenth century

John Crawfurd, British envoy to Siam and Cochin China (1828) provides greater detail, much of it accurate:

The only gems which are ascertained to be minerals of Siam, are the sapphire, the Oriental ruby, and the Oriental topaz [yellow sapphire]. These are all found in the hills of Chan-ta-bun [Chanthaburi], about the latitude of 12 degrees, and on the eastern side of the Gulf. The gems, from what we could learn, are obtained by digging up the alluvial soil at the bottom of the hills, and washing it. The gravel obtained after this operation is brought to the capital for examination. Both the ruby and sapphire of Siam are greatly inferior in quality to those of Ava [former capital of Burma]. Several specimens were shown to us during our stay, but none of them of any value. The mines of Chan-ta-bun, not with-standing this, are a rigidly guarded monopoly on the part of the King.

John Crawfurd, 1828

Pallegoix (1854) also gave an account of the mines:

Precious stones are found without doubt at several places in the Kingdom of Siam, as, when travelling, I often came across them in the beds of streams and amongst the gravels of rivers, but nowhere are there so many as in the province of Chanthaburi. The Chinese, who plant pepper all around the large mountain of Sa-bab collect them in quantities. In the high mountains, which surround the habitations of the Xong tribe, and in the six hills west of the town these stones are hidden in such quantities that the planters of tobacco and of sugarcane, who have established themselves at the foot of these hills, sell them by the pound: those of the smallest size cost 16 francs per pound, those of medium size 30 francs and those of the largest size 60 francs. The principal stones, which the Governor of Chanthaburi has shown me, are the following: large and perfect rock crystals, cat’s eyes the size of a small nut, topazes, hyacinths, garnets, sapphires of a deep blue and rubies of various tints. One day I went with a number of our Christians for a walk through the hills in the neighborhood of Chanthaburi and I found scattered over them black and greenish stones, semi-transparent (corundum), amongst which were garnets and rubies; within one hour we had collected two handfuls of them. As there are no lapidaries in the country, the inhabitants, who have collected some precious stones while planting their tobacco or sugarcane, do not know what to do with them and sell them at a low price to Chinese travelling traders, who forward them on to China. Yet, it must be noted that the King of Siam has reserved for himself certain localities where the best stones occur in greatest abundance; the Governor of Chanthaburi is charged with the exploitation and sees to it that the stones reach the palace, where some second-rate Malay lapidaries polish them and cut them into brilliants.

Mgr. Pallegoix, 1854 (modified from Gühler’s translation)

Na Wong village. From Smyth (1898) Five Years in Siam—From 1891 to 1896.

Na Wong village. From Smyth (1898) Five Years in Siam—From 1891 to 1896.

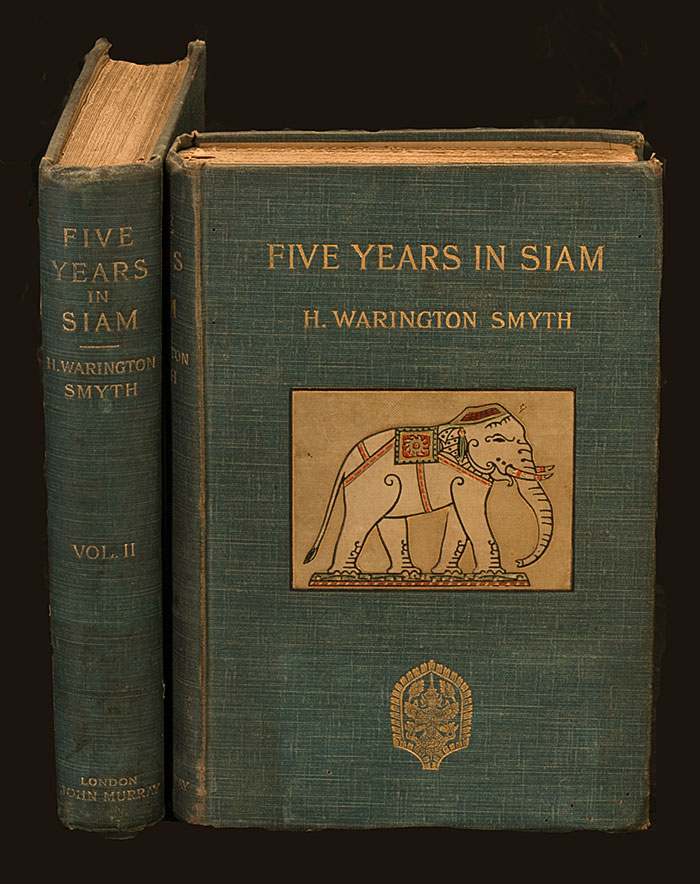

Pallegoix’s description accurately summed up the situation during the first half of the nineteenth century. Henry Louis (1894) visited the mines in 1892, but the most authoritative accounts of nineteenth-century Chanthaburi are those of H. Warington Smyth (1898, 1934), an Englishman employed by the Department of Mines of Siam from 1891–1896. Much of the following is based on his accounts.

About 1857, Shan traders from Mogok (Burma) rediscovered Chanthaburi’s mines, starting a gem rush which still continues. The rush supposedly began after a certain Nai Wong went fishing. Instead of prawns and fish, his net brought up gravel containing rubies. He exchanged these for clothes from Shan (Gula or Kula; กุลา) traders and the rush was on (Gühler, 1947). Thousands of Burmese Shans, who are ethnically related to the Thais of Siam, made their way to Chanthaburi, Trat and Pailin. These Shans developed the mines and their descendants hold prominent positions in Chanthaburi’s gem trade even today.

In 1857, Shan speculators leased the mines from the government and brought in their own men from Burma. However, there was little success until the appearance in 1880 of a financial genius named Mong Keng. Gathering all the mines into his hands and gaining control of the opium and gambling monopolies, too, he worked the mines profitably for many years, eventually becoming known as the "King of Precious Stones." With his fame also spread the fame of Pailin’s blue sapphires, not only in Siam, but also to India and Europe. In the early 1890s, however, the Government made a concession of parts of the district to a British firm, turning the Sapphire King into a serf almost overnight. Later, in 1895, another British firm, Siam Exploring Co., Ltd., received from the King of Siam the exclusive right to work the Pailin mines. They later also bought out the claims of the previous British company (Black, 1896).

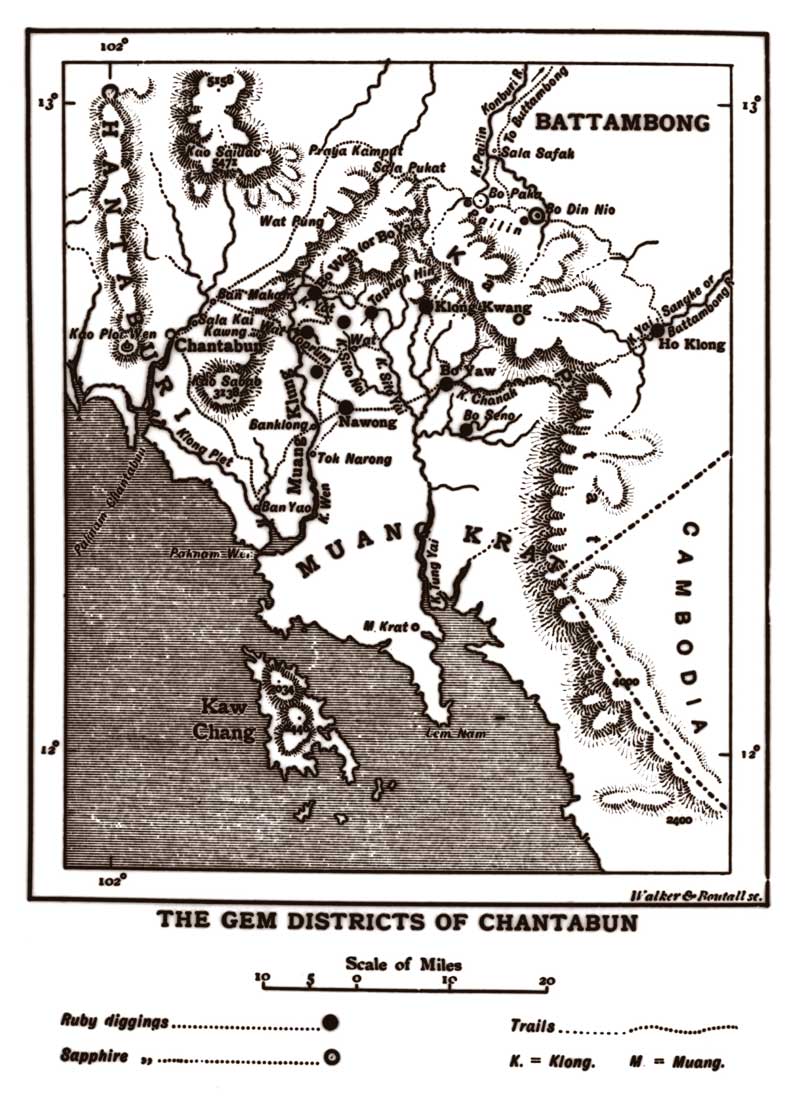

Map of Chantabun (Chanthaburi). From Smyth (1898) Five Years in Siam—From 1891 to 1896.

Map of Chantabun (Chanthaburi). From Smyth (1898) Five Years in Siam—From 1891 to 1896.

Nineteenth century mining and trading

Smyth (1898) has provided us with a fascinating picture of mining in Chanthaburi and Pailin during this period:

The Shân seems by nature designed for the pursuit of gems. He is bitten with the roving spirit, and in addition he has the true instinct of the miner, to whom the mineral he lives to pursue possesses a subtle charm, which constrains him never to rest or weary of its search against all odds. The sentiment is quite different to the avarice of the victims of a gold mania. The skill of the Gula [Shan] is no less than his energy. He detects color and recognizes quality with a rapidity and accuracy to which few attain. No Siamese, no Lao, no Chinaman can compete with him. The Burman is about his equal, but has not his industry or constitution, and is therefore chiefly found in the capacity of middleman, buying and exporting.

At first whole parties were decimated by the fever. Not one in thirty returned to the sea alive. But there were others to take their place, and gradually the clearing of the jungle, the improvement of communications, the superior shelter, and the comforts which were introduced had their effect; and although the mines still have an evil name, and the opening up of each new district calls for further sacrifices, the rate of mortality among the Shans is now comparatively moderate….

Should the Shâns therefore leave for any reason, there is no other force which can be utilized to do the necessary work. The departure of these people would doom the mines. They are necessary, if only to bury the others….

The Gula digger is proud and independent. He cherishes the freedom of his life, and he brooks not much official interference. Restraints which may be applied to the African negro will not do for him. When the [Siam Exploring] Company came to Nawong, diggers were notified (inter alia ) that if they worked on the company’s territory they must sell stones to its agents, at prices to be settled by the latter. This was felt to be an infringement of the right to sell in the open market, and was resented. Thereafter the company attempted to enforce the right of search on the persons and belongings of the diggers. Rather than submit they left en masse, some for the Pailin mines, others for their homes in Burma. The result was that, out of two thousand eight hundred diggers whom the company found in and about Nawong, a couple hundred were left when we visited the place; and at Bo Yaw, instead of twelve to fifteen hundred men, there were fifty-four at our visit.

Thus the Gula will be seen to be an individual whose susceptibilities must be taken into some consideration.

H. Warington Smyth, 1898, Five Years in Siam

Cover of H. Warington Smyth's Five Years in Siam—From 1891 to 1896. This is the most difinitive account of ruby and sapphire mining in Siam in the 19th century. From the William Larson Collection. Photo: Mix Dixon

Cover of H. Warington Smyth's Five Years in Siam—From 1891 to 1896. This is the most difinitive account of ruby and sapphire mining in Siam in the 19th century. From the William Larson Collection. Photo: Mix Dixon

Smyth also discusses the mining methods in some detail, as well as providing a fascinating account of the buying of gemstones:

In buying stones, it is well to remember you are entering the arena to pit your knowledge against the other man’s. He regards it as a sporting contest, and he would fleece or ruin his dearest friend as part of the game, if his dearest friend were fool enough to let him do it. The moment you bargain about a stone, a trial of strength (or knowledge) has begun between you, as much as if you were boxing or fencing. Everything is forgotten but the object in view, to protect yourself and get home on the person of your opponent.

Your eye must be in training too, and if you have not looked at a stone for six months, get some one else to do your buying for you, or you will be badly hit.

H. Warington Smyth, 1898, Five Years in Siam

The above is one of the best descriptions of the bargaining process, and is typical of the accurate and informative commentary provided in the writings of Smyth.

Chapel of the Mission, Chantaboun (Chanthaburi). Lying beside the Chanthaburi river, this small chapel, founded in 1707 A.D., has grown into the largest Catholic church in Thailand. Today the impressive Gothic structure is known as the Mary Immaculate Conception Cathedral. From Mouhot (1864) Travels in the Central Parts of Indo-China (Siam), Cambodia, and Laos, during the Years 1858, 1859, and 1860.

Chapel of the Mission, Chantaboun (Chanthaburi). Lying beside the Chanthaburi river, this small chapel, founded in 1707 A.D., has grown into the largest Catholic church in Thailand. Today the impressive Gothic structure is known as the Mary Immaculate Conception Cathedral. From Mouhot (1864) Travels in the Central Parts of Indo-China (Siam), Cambodia, and Laos, during the Years 1858, 1859, and 1860.

The twentieth century

In 1907, Battambang Province, containing the valuable Pailin mines, was returned to the French in Cambodia. Up until that time, Pailin supplied as much as 90% of the world’s fine sapphires. Although production continued to pass through Chanthaburi and Bangkok, after 1907 Thailand’s production of sapphires dropped dramatically from the loss of Pailin. Discovery of new sapphire mines in Kanchanaburi and Phrae helped somewhat, but with the loss of Pailin, Thailand lost a major portion of its sapphire mining potential.

In 2009, the Mary Immaculate Conception Cathedral in Chanthaburi was refurbished. It now includes this 1.3 m icon of Mary, inlaid with over 20,000 carats of sapphire and other gems. Photo © Richard W. Hughes.

In 2009, the Mary Immaculate Conception Cathedral in Chanthaburi was refurbished. It now includes this 1.3 m icon of Mary, inlaid with over 20,000 carats of sapphire and other gems. Photo © Richard W. Hughes.

Things went better for ruby. In 1962, a military coup slammed the door shut on the world's most famous ruby mines. Almost overnight, the only ruby available was stones from the Thai-Cambodian borer. This brought a renaissance in Thailand's gem trade, as many dealers and cutters left Burma for Thailand. Suddenly Thailand's star was rising.

But ruby wasn't the only game in town. Chanthaburi traders had long been venturing to Australia for sapphire and in the mid-1970s, they discovered a method of heated geuda sapphire from Sri Lanka. This further cemented Chanthaburi's position as the world center for rubies and sapphires.

By the late 1990s, most of the Thai and Cambodian mines were exhausted. But rather than mourn the passing, Chanthaburi's resourceful gem hunters began roaming the world. From Sri Lanka to East Africa to Madagascar, wherever gems were found, Chanthaburi people were on the scene. Because of this, gem dealers from around the globe now come to Chanthaburi to offer gems of both the precious and semi-precious variety. Chanthaburi is no longer just about ruby and sapphire, but has truly become the Colored Gem Capital of the globe.

Foreign buyers in Chanthaburi's weekend gem market. Once only the province of ruby and sapphire, today Chanthaburi's market is home to a variety of gems from around the world. Photo © Richard W. Hughes.

Foreign buyers in Chanthaburi's weekend gem market. Once only the province of ruby and sapphire, today Chanthaburi's market is home to a variety of gems from around the world. Photo © Richard W. Hughes.

Mining areas in Chanthaburi, Trat and Pailin

Khao Ploi Waen & Bang Kha Cha

At Khao Ploi Waen (เขาพลอยแหวน; literally ‘Hill of Gems’) and Bang Kha Cha (บางกะจะ), blue, green, yellow and black-star sapphires are found in small amounts. Ruby is entirely absent. Khao Ploi Waen is located just 6.5 km west of Chanthaburi and consists of placers derived from an isolated butte some 70 meters above the surrounding plains. This is said to have been the first place in Thailand where corundum was found. The hill consists of a volcanic plug and sapphires are mined from placers derived from the lava. Mines are scattered all around the base of the hill. Formerly they consisted of simple pit mines, but today mechanized mines have replaced them. This is the last area in Chanthaburi and Trat that is still being mined, the other deposits having been completely depleted.

The blue sapphires found here are of a pure blue color, but suffer from being too dark. Good black-star and green sapphires are found, but the mine is most famous for producing yellow sapphires of a characteristic Mekong Whisky golden-yellow to orange color. This color is much in demand in the local market and fine stones sell for as much as US$500–1000/ct or more. The rare “golden-star” black-star sapphires are also found here and fetch good prices locally. A golden-star black-star sapphire results from hematite silk unmixing in an otherwise yellow sapphire. The more common, white-rayed black-star sapphires contain hematite silk in blue or green sapphires. Twelve-rayed black-star sapphires are common, and result from both hematite and rutile silk in the same stone.

Highly sought-after "Mekong Whiskey" yellow sapphires from Bang Kha Cha near Chanthaburi. Such stones are increasingly scarce as the mines are nearly depleted. Photo © Richard W. Hughes.

Highly sought-after "Mekong Whiskey" yellow sapphires from Bang Kha Cha near Chanthaburi. Such stones are increasingly scarce as the mines are nearly depleted. Photo © Richard W. Hughes.

The placers of Bang Kha Cha are located but a few kilometers from Khao Ploi Waen and produce an identical suite of colors. They are situated on a flat swampy plain on the Klong Hin River estuary, which is underlain by alluvium. Not only are the swamps mined, but also the river bottom. Zircon and pyrope garnets are also found at both localities.

One of the last remaining sapphire miners at Khao Ploi Waen examines a find. Photo © Richard W. Hughes.

One of the last remaining sapphire miners at Khao Ploi Waen examines a find. Photo © Richard W. Hughes.

Tok Phrom, etc.

The second major corundum zone is found behind the granite mountain of Khao Sabab, which dominates the view from Chanthaburi. These mines are right on the border between Chanthaburi and Trat Provinces, and include:

- Bo Waen (Bo Welu; บ่อเวฬุ)—ruby only

- Bo Na Wong (นาวง)—ruby only

- Tok Phrom (ตกพรม)—mainly blue sapphire

- Bo I Rem (บ่ออีเลม)—mainly blue sapphire

Although transportation to, and roads within, this area are poor, a number of large mechanized mines can be found. Mostly ruby is mined, with the exception of I Rem, where sapphires dominate. The sapphires are of a deep, pure blue color and resemble those from nearby Pailin. This material is good for cutting small sizes (one-half carat or less) because it holds the color well, but larger stones tend to be too dark. As with the other mines in Thailand, the deposits are alluvial or eluvial in nature. Output of ruby from this district forms a significant portion of Thailand’s ruby exports.

Bo Rai & Nong Bon

The third major area is further to the east, in Trat Province, and includes the large and well-known mechanized mines at Nong Bon (หนองบอน) and Bo Rai (บ่อไร่). These were the largest ruby mines in Thailand and are accessible by good roads. Only ruby was found here, with larger stones found at Nong Bon, but with finer colors coming from Bo Rai. The mines at Bo Rai and Nong Bon were mechanized, with bulldozers, earth movers and other heavy equipment in use; those across the border in Cambodia, however, were usually primitive pit mines only, due to the ongoing war.

In terms of stone sizes, Thai rubies, like all other rubies, are found in much smaller sizes than sapphires. With the onset of mechanized mining in the 1970's, larger gems were unearthed, including several of fine quality in the 10-ct plus range. The biggest ever found in the area was a 150-ct giant (in the rough) unearthed in 1985 in Trat Province. Due to the even coloration of Thai rubies, most cut gems above five carats tend to be overly dark.

Rough sapphire at Pailin, Cambodia. Photo © Richard W. Hughes.

Rough sapphire at Pailin, Cambodia. Photo © Richard W. Hughes.

Holding a gem is like holding a rainbow in your hand. Their beauty doesn't just bring happiness to the beholder, but also prosperity to those whose hands the gem has also passed through. Anonymous

Pailin, Cambodia

Further east, across the border in Cambodia, are the famous Pailin gem fields. The Cambodian city of Pailin (the ancient Khmer word for 'blue sapphire') is steeped in local folklore, particularly the temple at Pailin's Phnom Yat:

Phnom Yat figures strongly in Cambodian folklore. As the story goes, people were hunting animals in the forest around Pailin, where they encountered a magical old lady living as a hermit in the mountains, called Yiey (= grandma) Yat, who didn't like the people killing her animals. She told them that if they stopped killing the animals, she would reward them at a certain stream on Mount Yat. The people went there and saw an otter (= pey) playing (= leng) in the stream. The otter swam up to them and opened his mouth, which was full of gems. As a result, the area became known as the place of 'pey leng', which became corrupted by the Thai translation to Pailin. Fancy that! Nowadays, many people go to the magical shrine of Yiey Yat to ask her for riches. The shrine is located near the top of the hill, where there is a small statue of Yiey Yat. There is also a statue of the magic otter. In fact, there are lots of interesting statutes on Phnom Yat. For example, there are scenes from Buddhist hell, such as liars having their tongues pulled out, or adulterers impaled on a thorn tree.

There is an old stupa at the top behind everything else. This is the burial place of the ashes of Rattanak Sambat, the father of another Cambodian literary figure named Khun Niery. This true story was written up in a famous novel by Nheck Tem called Pailin Rose. In the story, Chao Chet, a poor orphan who came to work for Rattanak Sambat and fell in love with his daughter. But the father wanted her to marry the governor of Sanker District (east of Battambang), named Balatt, while Chao Chet became only the driver for Balatt. The car broke down on the way back to Pailin, and they were attacked by a robber. Balatt proved to be a coward and hid under the car, while Chao Chet was the hero who saved the day. As a result, Rattanak allowed Chao Chet to marry Khun Niery.

Andy Brouwer, Cambodia Tales

In Cambodia, the rise of the bloody Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia (Kampuchea) during the early 1970s halted for several years all mining activity. With the installation of the Vietnamese-sponsored government in 1979 mining was again started, but limited due to the raging guerrilla war.

The war in Cambodia inflicted tremendous suffering on civilians in Vietnam, with food and goods of all kinds being in short supply. This resulted in black humor among foreign aid personnel stationed there. The following is a sample, courtesy of Bangkok writer, John Hoskin:

Vietnamese cable to Moscow: Please send aid!

Soviet reply: Please tighten belts.

Vietnamese answer to Moscow: Please send belts.

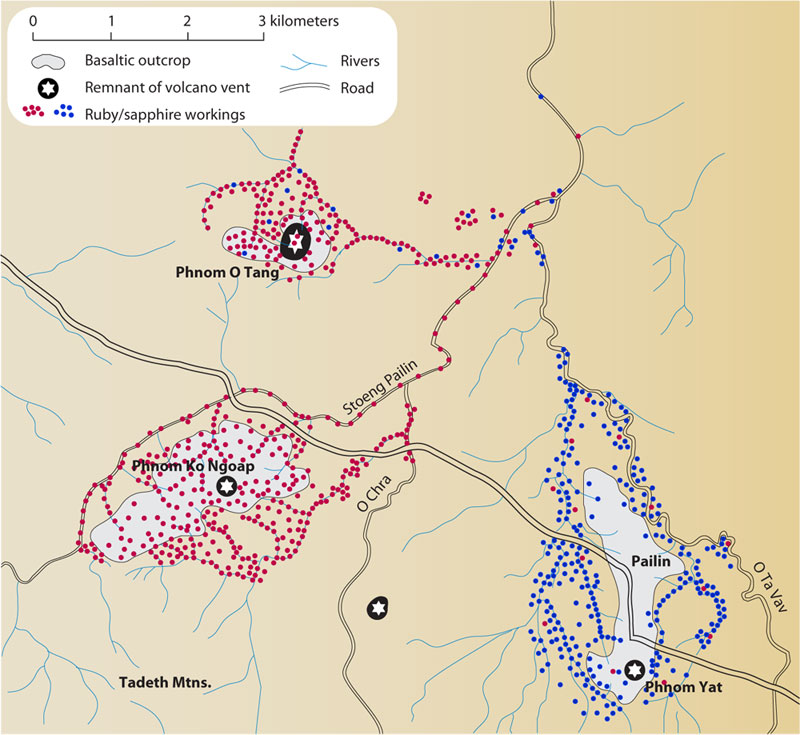

Map of Pailin's ruby & sapphire deposits. Map © Richard W. Hughes (after Jobbins and Berrangé, 1981).

Map of Pailin's ruby & sapphire deposits. Map © Richard W. Hughes (after Jobbins and Berrangé, 1981).

In 1991, a peace agreement was reached, resulting in the withdrawal of Vietnamese troops. Eventually the last remaining pockets of Khmer Rouge resistance were wiped out and by 1999, the country was largely at peace. The jungles surrounding Pailin were among the final bastions of the Khmer Rouge. In Pailin, the Khmer Rouge Brother No. 3, Ieng Sary, set himself up almost in the manner of a feudal dictator, selling the region's resources to the highest bidders. During the decade that followed the peace agreement, UN peacekeeping troops moved in, along with Thai miners (and loggers). As of this writing (2011), most of Pailin's mines are now also exhausted.

Qualities & varieties

Although the rubies from Pailin are of good quality after heat treatment (virtually identical to those from Thailand), it is the blue sapphires that are its major boast. In fact, the word for blue sapphire in the Thai language is pailin (ไพลิน), its name being taken from this important locality. Ranging in color from a medium to deep blue, the material is particularly fine in small sizes. Pailin sapphires strongly resemble those found at Bo I Rem in Thailand, except that the latter tend to be darker. This is also the major flaw with most Pailin stones; it does mean, however, that small stones (below 0.50 ct) hold their color well. Star sapphires have been found at Pailin but are rare. Zircon and pyrope garnets are found, in addition to corundum.

One interesting feature of the corundums from the Pailin area is the virtual absence of colorless, yellow and green sapphires. Local diggers only occasionally find a yellow stone; the other varieties are not found at all. Color-change sapphires are found with some frequency, as in Thailand, and can often be had for a song as they are mixed into parcels of inferior rubies. These stones appear a light to deep-greenish violet in daylight and change to a purplish pink in incandescent light, similar to those from Umba (Tanzania).

Lava flows at Pailin have formed four separate hills around which the mines are situated. Westernmost are those of Phnom O Tang and Phnom Ko Ngoap, rising about 40–60 m above the surrounding plain. These two areas produce primarily ruby, with small amounts of sapphire. The rubies here are identical to those found in nearby Thailand. To the east at Phnom Yat, near the small town of Pailin, the situation is reversed, with sapphires dominating. It is from this locality that most of the famous Pailin sapphires have been unearthed. The fourth lava outcrop, located in a coffee plantation, is only 200 meters in diameter and is thought to be a volcanic pipe.

One of Pailin's last ruby miners. Photo © Richard W. Hughes.

One of Pailin's last ruby miners. Photo © Richard W. Hughes.

References & further reading

- Bacon, G.B. (1893) Siam, the Land of the White Elephant, as it was and is. New York, Charles Scribner's Sons, 296 pp.

- Berrangé, J.P. and Jobbins, E.A. (1976) The geology, gemmology, mining methods and economic potential of the Pailin ruby and sapphire gem-field, Khmer Republic. Institute of Geological Sciences, Overseas Division, Report No. 35, 32 pp. + maps.

- Brown, G.F., Buravas, F. et al. (1951) Geological reconnaissance of the mineral deposits of Thailand. Bulletin, US Geological Survey, Vol. 984, 183 pp., 20 pls., 38 figs., 4 tables.

- Chang-Glom, K. (1988) Chanthaburi. [in Thai]. Sara-Kadee, Bangkok, 235 pp.

- Chonpairot, M., Photisane, S. et al. (2009) Guideline for conservation, revitalization and development of the identity and customs of the Kula ethnic group in northeast Thailand. The Social Sciences, Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 167–173.

- Coenraads, R.R., Vichit, P. et al. (1995) An unusual sapphire-zircon-magnetite xenolith from Chanthaburi gem province, Thailand. Mineralogical Magazine, Vol. 59, No. 3, pp. 467–481.

- Crawfurd, J. (1828) Journal of an Embassy to the Courts of Siam and Cochin China. London, Henry Colburn, reprinted 1967, Oxford University Press, London, see pp. 419–420.

- Gühler, U. (1947) Studies of precious stones in Siam. Siam Science Bulletin, Vol. 4, pp. 1–38.

- Hoskin, J. (1987) The Siamese Ruby. Bangkok, World Jewels Trade Center, 119 pp.

- Hughes, R.W. (1997) Death of the Thai ruby. AGA Cornerstone, Summer, pp. 1, 3–6.

- Hughes, R.W. (1997) Ruby & Sapphire. Boulder, CO, RWH Publishing, 512 pp.

- Hughes, R.W. (2009) Red sky at dusk: Hunting the last Siamese ruby miner. LotusGemology.com.

- Jobbins, E.A. and Berrangé, J.P. (1981) The Pailin ruby and sapphire gemfield, Cambodia. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 17, No. 8, Oct., pp. 555–567.

- Keller, P.C. (1982) The Chanthaburi-Trat gem field, Thailand. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 18, No. 4, Winter, pp. 186–196.

- Koizumi, J. (1990) Why the Kula wept: A report on the trade activities of the Kula in Isan at the end of the 19th Century. Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 28, No. 2, September, pp. 131–153.

- Loubère, S., de la (1693) A New Historical Relation of the Kingdom of Siam. London, reprinted by White Lotus, Bangkok, 1986, 286 pp.

- Louis, H. (1894) The ruby and sapphire deposits of Moung Klung, Siam. Mineralogical Magazine, Vol. 10, No. 48, pp. 267–272.

- Ma Huan (1970) Ying-Yai Sheng-Lan ‘The overall survey of the ocean’s shores’ [1433]. Cambridge, Hakluyt Society, Extra Series, No. 42, 393 pp.

- Mouhot, H. (1864) Travels in the Central Parts of Indo-China (Siam), Cambodia, and Laos, during the Years 1858, 1859, and 1860. London, John Murray, 2 Vols., xix, 303, viii, 301 pp.

- Mouhot, H. (1992) Travels in Siam, Cambodia, and Laos. Singapore, Oxford University Press, 2 vols. in one, reprint of the first English ed. (ca. 1860), xix, 303, viii, 301 pp.

- Pallegoix, M. (1854) Description du Royaume Thai ou Siam. Paris, see pp. 117–121.

- Pardieu, V. (2009) Pailin, Cambodia (Dec. 2008–Feb. 2009). Concise Field Report, Volume 1, GIA Laboratory, Bangkok,

- Phillips, G. (1887) The seaports of India and Ceylon [Ma Huan’s account of Ceylon and the Kingdom of Siam (Hsien-lo-Kwo), 1408]. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, China Branch, Vol. 20–21, pp. 209–226; 30–42.

- Smyth, H.W. (1895) Notes on the Geography of the Upper Mekong. Brisbane, Australian Association for the Advancement of Science, pp. 533–551.

- Smyth, H.W. (1895) Notes of a Journey on the Upper Mekong, Siam. London, Royal Geographical Society, reprinted 1998 by White Lotus, Bangkok as: Exploring for Gemstones on the Upper Mekong, 109 pp.

- Smyth, H.W. (1898) Five Years in Siam—From 1891 to 1896. New York, Scribner’s, 2 Vols., Reprinted 1994, White Lotus, Bangkok, 330, 337 pp.

- Smyth, H.W. (1926) Sea-Wake and Jungle Trail. New York, Frederick A. Stokes, 323 pp.

- Smyth, H.W. (1934) Chase and Chance in Indo-China. London, Blackwood, 379 pp.

- Suksamran, N. (2009) Staying true to their roots: Thai Catholics in Chanthaburi are mostly descended from Vietnamese immigrants. Bangkok Post, Bangkok, May 12.

- Vichit, P., Vudhichativanich, S. et al. (1978) The distribution and some characteristics of corundum-bearing basalts in Thailand. Journal of the Geological Society of Thailand, Vol. 3, pp. M4–1 to M4–38.

- Vichit, P. (1992) Gemstones in Thailand. Dept. of Mineral Resources, Bangkok, Thailand, Piancharoen, C., ed., In Proceedings of a National Conference on Geologic Resources of Thailand: Potential for Future Development, Bangkok, Supplementary Volume, pp. 124–150.

- Wikipedia. The Franco-Siamese War of 1893.

About the author

Richard W. Hughes is one of the world’s foremost experts on ruby and sapphire. The author of many books and over 170 articles, his writings and photographs have appeared in a diverse range of publications, and he has received numerous industry awards. Co-winner of the 2004 Edward J. Gübelin Most Valuable Article Award from Gems & Gemology magazine, the following year he was awarded a Richard T. Liddicoat Journalism Award from the American Gem Society. In 2010, he received the Antonio C. Bonanno Award for Excellence in Gemology from the Accredited Gemologists Association. The Association Française de Gemmologie (AFG) in 2013 named Richard as one of the Fifty most important figures that have shaped the history of gems since antiquity. In 2016, Richard was awarded a visiting professorship at Shanghai's Tongji University. 2017 saw the publication of Richard and his wife and daughter's Ruby & Sapphire • A Gemologist's Guide, arguably the most complete book ever published on a single gem species and the culmination of four decades of work in gemology. In 2018, Richard was named Photographer of the Year by the Gem-A, recognizing his photo of a jade-trading market in China, while in 2020, he was elected to the board of directors of the Accredited Gemologists Association and was appointed to the editorial review board of Gems & Gemology and The Australian Gemmologist magazine. In 2022, Richard published Jade • A Gemologist's Guide, while 2024 brought Broken Bangle • The Blunder-Besmirched History of Jade Nomenclature. His jade trilogy was completed in 2025 with his translation of Heinrich Fischer's Nephrite and Jadeite.