The author makes his first pilgrimage to Burma's Mogok Stone Tract.

May 1996 – All across SE Asia, the monsoon is cause for celebration, for the great rains that sweep out of the South China Sea each May nurtures their livelihood – rice. In Burma's remote Mogok Stone Tract, water nurtures an entirely different crop – pigeon's blood rubies – the finest in the world. And this year, the monsoon started early. Rain is falling and the population is smiling. But today's smiles are brighter than before. Today, the people of Mogok smile because, for the first time in decades, tomorrow looks better than today.

A young boy frolicking in the water near Mogok's Ho Mine, famous for producing some of the world's finest rubies. Water in Burma's Mogok Stone Tract brings smiles to all. Not only does the area's heavy rain (over 150 inches yearly) play a vital role in freeing rubies and other gems from their mountain birthplaces, but water is also a necessary element of the area's mining industry. Photo: R.W. Hughes

A young boy frolicking in the water near Mogok's Ho Mine, famous for producing some of the world's finest rubies. Water in Burma's Mogok Stone Tract brings smiles to all. Not only does the area's heavy rain (over 150 inches yearly) play a vital role in freeing rubies and other gems from their mountain birthplaces, but water is also a necessary element of the area's mining industry. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Mogok: Valley of Rubies

The exact date when rubies were first discovered at Mogok is unknown. No doubt the first humans to settle the area found rubies and spinels in the rivers and streams. But according to local legend, the origins of the ruby mines were as follows:

Long before the Buddha walked the earth, the northern part of Burma was said to be inhabited only by wild animals and birds of prey. One day the biggest and oldest eagle in creation flew over a valley. On a hillside shone an enormous morsel of fresh meat, bright red in color. The eagle attempted to pick it up, but its claws could not penetrate the blood-red substance. Try as he may, he could not grasp it. After many attempts, at last he understood. It was not a piece of meat, but a sacred and peerless stone, made from the fire and blood of the earth itself. The stone was the first ruby on earth and the valley was Mogok.

This is the legendary Valley of Rubies, impenetrable due to the deadly serpents which covered its floor. To retrieve rubies, men would cast lumps of meat into the valley via catapults. Rubies would become attached to the meat, which was then carried out of the valley by large birds of prey. After the birds had sated their appetites, men would climb into their nests and retrieve the rubies from their droppings.

An Oriental miniature dated 1582, representing the Valley of Serpents, guarded by snakes. Eagles carry in their beaks pieces of meat in which gems are embedded, illustrating an Indian legend that appears in the tale of Sinbad the Sailor in the Thousand and One Arabian Nights. Illustration courtesy of the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

An Oriental miniature dated 1582, representing the Valley of Serpents, guarded by snakes. Eagles carry in their beaks pieces of meat in which gems are embedded, illustrating an Indian legend that appears in the tale of Sinbad the Sailor in the Thousand and One Arabian Nights. Illustration courtesy of the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

A City Built on Rubies

While rubies have been scraped out of the dirt at Mogok since prehistoric times, this underground wealth has not always enriched those living directly above. As knowledge of the crimson stones spread, more powerful rulers from outside the area levied tribute, payable in rubies. By the sixth century, local inhabitants were paying two viss (about 3.2 kg) of stones yearly to the central government.

By the time the first Europeans visited Burma in the fifteenth century, the gem wealth of the country was well known. In 1597 AD, when the Burmese monarch, Nuha-Thura Maha Dhama-Yaza tired of getting his rubies second-hand, he simply annexed the district, exchanging a small piece of his territory to the hapless Shan saopha (prince), who was powerless to stop him. Even today, a look at a map of Burma illustrates the remnants of this one-sided deal. The border separating Sagaing Division from the Shan State makes a sudden jog to enclose the area at Mogok.

After 1597 AD, the Mogok Stone Tract was operated as the private province of whoever had the strongest army. Mostly, this was the Burmese kings, who decreed that all stones above the value of Rs2000 were property of the crown. Concealing them was punishable by torture and death. So harsh was this rule that, by the time of the British annexation of Upper Burma in 1885, much of the local population had fled.

Miners at Inn Chauk, just north of Mogok, are dwarfed by massive limestone boulders as they hunt for rubies. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Miners at Inn Chauk, just north of Mogok, are dwarfed by massive limestone boulders as they hunt for rubies. Photo: R.W. Hughes

The brief period between the annexation and arrival of British troops represented the first time in centuries that miners were able to operate independent of state control. It was also to be the last. During the colonial period, Britain leased out the mines to an ill-fated London syndicate (the Burma Ruby Mines Ltd.); since independence in 1948, the Burmese government has kept a tight rein on the mines. From 1962 onwards, the country embarked on the "Burmese Road to Socialism," which brought further restrictions on gem mining and trading. The industry's nadir was reached in 1969, when the Ministry of Mines banned private exploration and mining of gems, effectively nationalizing the entire trade in precious stones.

In the past few years, trading in Burma has undergone a quiet revolution. Just four years ago, private gem trading was illegal; today, both rough and cut stones can be freely purchased by foreigners with dollars from licensed traders, with only a 10% export tax to be paid. Thus, for the first time in over 30 years, private trading and export of gems is both simple and legal. Keep in mind, though, that the purchase of gems in source countries such as Burma or Sri Lanka is strictly for professionals. Good stones are rare, even in Burma and synthetics and imitations abound. In short, if you're not an expert, stay away.

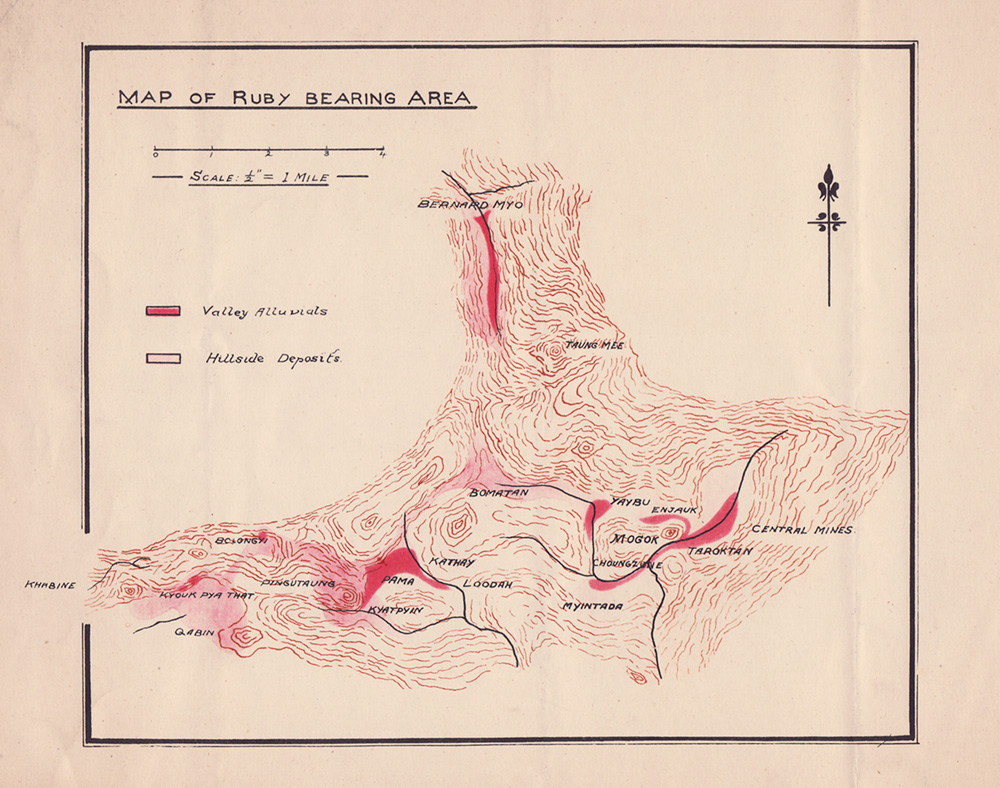

Rare map of Myanmar's Mogok Stone Tract. From The Burma Ruby Mines by Atlay & Morgan (1905)

Rare map of Myanmar's Mogok Stone Tract. From The Burma Ruby Mines by Atlay & Morgan (1905)

Pilgrimage to Mogok

I first began traveling the world as a teenager, and those travels eventually brought me to Burma, at age 19. It was there that I saw my first Burmese ruby. I was immediately hooked, head-over-heels in love with a pebble dug out of the ground in a remote Burmese valley. It wasn't simply the value which drew me to ruby. If it was value, I would just go out and get a few kilos of gold. No, it was something else entirely, something I couldn't quite put my finger on.

My love for rubies eventually developed into a desire to visit their source. Everyone has their own pilgrimage to make, their own personal Mecca. My Mecca was Mogok. But the area had been strictly off-limits to foreigners since 1962. Finally, in April of 1996, it happened. The Mogok door cracked open. This is what I found.

Mogok (1500 m) is located some 210 km and seven hours by road northeast of Mandalay. Consisting of heavily-jungled hills rising to a height of 2347 m above sea level, the Stone Tract covers about 1000 sq km, although only a portion (180 sq km) is gem bearing. Considered one of the most scenic areas in Burma, it is home to a number of colorful ethnic groups, as well as a variety of wildlife, including elephants, tiger, bear and leopard.

The town itself is today a bustling city; the entire district probably contains 300,000–500,000 inhabitants. These consist of Burmese and Shan (Buddhist), Nepalese Gurkhas (Hindu), Lisu (Christian and Animist), along with a smattering of Muslims, Sikhs and those of Eurasian origin. The region's population has swelled tremendously in recent years, following the Burmese government's liberalization of the gem trade.

A Kokang Chinese miner emerges from a lu-dwin at Kyauk Saung, near Mogok. Photo: R.W. Hughes

A Kokang Chinese miner emerges from a lu-dwin at Kyauk Saung, near Mogok. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Occurrence of Ruby & Mining Methods

Mogok's rubies occur in a crystalline limestone (marble). Bit by bit, millions of years of weathering freed the rubies from their marble womb, carrying them down from the hills to the valley floors, where they have settled in the bottom of the streams and rivers. It is from these ancient river gravels (locally termed byon) that the majority of stones have been recovered.

Five traditional types of mines exist in Mogok:

- The pit method for mining the valley alluvials. Small circular pits are termed twin-lon ('twin'), with larger pits known variously as lebin, kobin and inbye. The twin-lon was once the most common type of mining, but today it is rarely seen. More common are the lebin and kobin.

- The hmyaw-dwin ('hmyaw') or open-trench method, for excavating hillside deposits. Since the easily reached valley alluvials are now largely exhausted, hmyaw mining has largely replaced the twin-lon.

- The lu-dwin ('lu'), where gem-bearing materials are extracted from limestone caves and fissures.

- Quarrying (tunneling) directly into the host rock to extract rubies and sapphires.

- Open cast, which has been performed since the time of the British Burma Ruby Mines Ltd.

Some of the richest ruby finds have been made within lu-dwin caverns and crevices. One cavern proved so vast in size and the depth of the byon so great, that hmyaw-dwin and twin-lon were set up inside the cavern itself. Unfortunately the roof caved in, putting an ignoble halt to the proceedings. I was told of a cave near Yadana Kaday-kadar with a room the size of a football field, while another lu-dwin near Chaunggyi was said to be 2.4 km long.

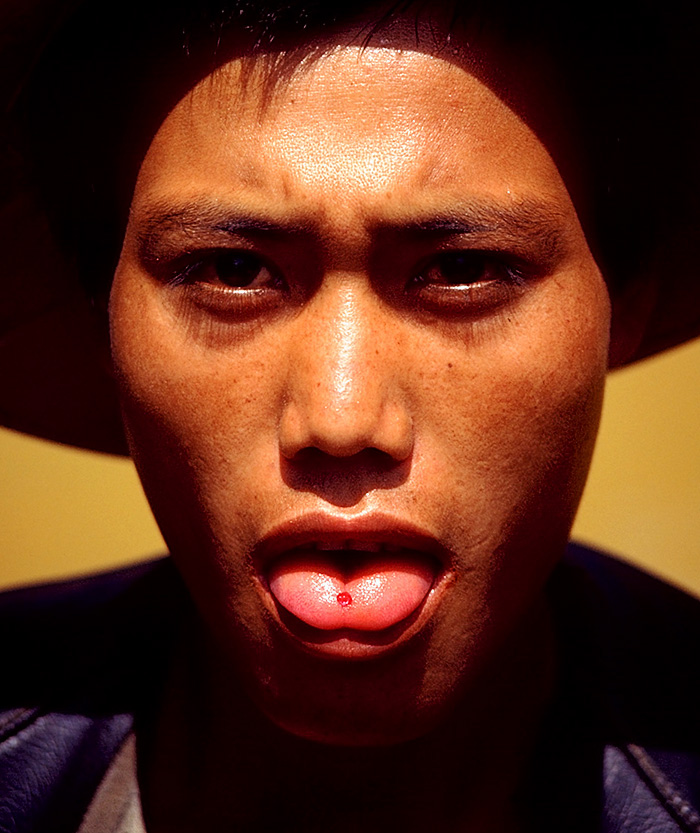

Important goods are kept close at hand. In the photo above, a miner at Mogok's Padan Sho mine shows off his latest find. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Important goods are kept close at hand. In the photo above, a miner at Mogok's Padan Sho mine shows off his latest find. Photo: R.W. Hughes

The lu-dwin is by far the most dangerous type of mining, since it generally involves climbing down into narrow cracks and crevices which may be several kilometers in length and over a kilometer deep. In 1992, several miners died in a cave-in at a lu-dwin at Than Ta Yar.

One particularly rich lu-dwin near Bawpadan was termed the "Royal Lu" because, during the time of the Burmese monarchy, gems found there were of such high quality that they had to be turned over to the king. During my second visit to Mogok (May, 1996), I spent an entirely enjoyable afternoon scurrying through the long-abandoned crevices of Bawpadan's Royal Lu.

Richard Hughes exploring the Royal Lu near Bawpadan in Myanmar's Mogok Stone Tract. Photo: Olivier Galibert

Richard Hughes exploring the Royal Lu near Bawpadan in Myanmar's Mogok Stone Tract. Photo: Olivier Galibert

Washing the Byon

Once sufficient byon is obtained, it is transported to the washing area, where, in a process similar to panning for gold, the heavier ruby is separated from the lighter waste.

Output from mechanized mines goes to a washing plant, to be separated by machine. Today, the government operates a central washing plant, but most mechanized mines have their own washing plants.

The Kanasé Custom

Almost inevitably, some gems escape capture and are carried away to the tailings. According to local custom, tailings may be searched by anyone, with all stones found becoming property of the finder. Under the British Company, however, this was later restricted to women only; any man who so much as bent down to touch a stone on the ground, unless a worker or license holder, was subject to imprisonment. Thus, today is largely women and children who mine in this way. They are termed kanasé ma (tailings women).

This custom has resulted in the wholesale theft of large numbers of stones, as well as providing a convenient method for the disposal of stolen goods. The way it works is thus: a dishonest workman may catch sight of a stone. He then passes it secretly to a nearby kanasé woman or tells her where to search for it. Moments later, there is a shout of joy as the woman has just "uncovered" a stone which, by custom, is hers to keep. The British Company went to great lengths to prevent the theft of stones, enclosing the sorting areas, requiring workers to wear steel masks so that stones could not be swallowed, etc. However, all this was to no avail because of the kanasé custom.

A young kanasé ma breaks marble in search of rubies at Kyauk Saung, in Myanmar's Mogok Stone Tract. She told the author it was her summer holiday, and that she would be back in school in a few days. Photo: R.W. Hughes

A young kanasé ma breaks marble in search of rubies at Kyauk Saung, in Myanmar's Mogok Stone Tract. She told the author it was her summer holiday, and that she would be back in school in a few days. Photo: R.W. Hughes

|

The Nga Mauk Ruby Although the Burmese monarchs laid claim to all rubies worth over Rs2000, the case of the Nga Mauk Ruby illustrates that many of the large crimson gems slipped through their hands. Nga Mauk, a poor miner, uncovered a fine ruby weighing about 560 ct during the reign of one of the Burmese monarchs. Noticing a crack that split the piece neatly in two, he presented one half to the King, and secretly sent the other half to Calcutta for sale. But the king learned of the fraud. As a warning to others, he ordered all the inhabitants of Nga Mauk's village to be burned alive. The remains of this horrible cremation can be seen at a place called Laungzin, which means "fiery platform." Nga Mauk's wife, Daw Nann, apparently escaped, for she is said to have watched his blazing death from atop a hill near Kyatpyin. Today, this hill is called Daw Nann Gyi Taung ('the hill where Daw Nann looked down'). As for the Nga Mauk Ruby, the second half was eventually purchased and returned to Burma. The two pieces were cut in Mandalay, one forming a grand stone weighing 98 ct called the Nga Mauk Ruby, the other weighing 74 ct, and called Kallahpyan ('returned from India'). Both pieces disappeared when the British annexed upper Burma in 1885. |

Brokers

The role of brokers is important, both at Mogok and further north at the Hpakan jade mines. Each dealer employs them to act as his eyes and ears.

Brokers not only assist in valuations and sales, but also obtain intelligence about what valuable stones have been recently mined, who the owners are, and, just as importantly, who the stones are being offered to and the prices bid. Owners of valuable stones do their best to keep details secret, for if a piece is bid upon, when the spies of other dealers learn of the bid, no one will offer more. In other words, if one dealer believes it is worth only 50,000 Kyat, then why offer more?

This situation results in purchases taking place in a cloak-and-dagger atmosphere as both buyer and seller seek to conceal their activities. Stolen stones in particular may be offered at remote jungle rendezvous', sometimes in the dead of the night with only a hand torch as illumination. Legitimate goods may also be offered in this way, being represented as stolen in the hope that this would increase the buyer's feeling that he is getting a steal of a deal.

Pigeon's blood rubies and spinels straight from the mine. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Pigeon's blood rubies and spinels straight from the mine. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Mogok's Gem Markets

A number of gem markets operate in the Mogok area, each specializing in a particular type of stone. One of the most interesting is the late-afternoon market at Myintada, where colorfully-clad women can be seen haggling over all kinds of small rough rubies. Each broker is equipped with the tools of the trade – a wide-brimmed hat to keep the sun off, a small brass plate upon which the stones are placed, and, most importantly, a keen eye.

Examining rubies in one of Mogok's many markets. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Examining rubies in one of Mogok's many markets. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Burmese Rubies Compared

Until the discoveries in Vietnam in the late 1980's, Burmese rubies were without peer. Other sources, such as Kenya and Afghanistan, produced the occasional stone which could stand with Burma's best, but these were exceptions. In historic terms, Mogok rubies are in a class by themselves.

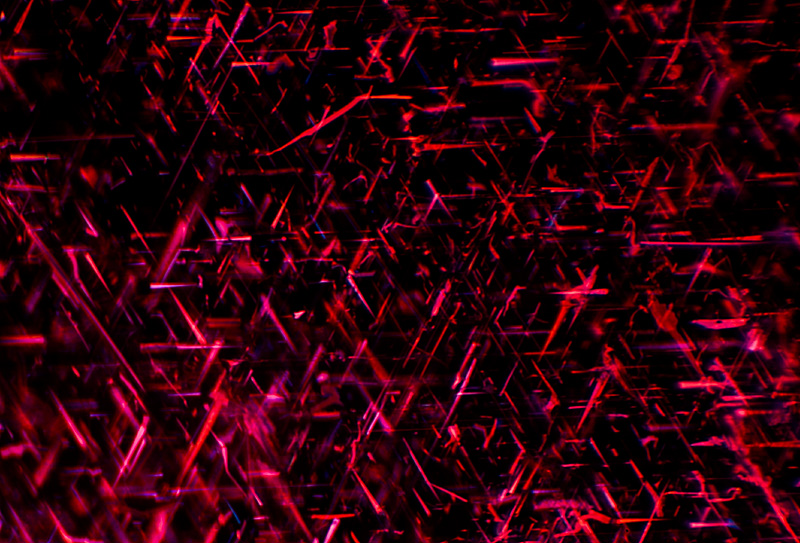

Smooth as silk

The color of a fine Mogok ruby is due to a combination of two factors. First is something gemologists call "silk." Silk refers to tiny needle inclusions which scatter light onto facets that would otherwise be extinct. This gives the color a velvety softness, as well as spreading it across a greater part of the gem's face. Thai/Cambodian rubies contain no rutile silk, and thus possess more extinction. But too much silk is not a good thing. The best rubies have just a trace of extremely fine silk scattered throughout.

Rutile silk in a Burmese ruby. These inclusions scatter light, helping to reduce extinction. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Rutile silk in a Burmese ruby. These inclusions scatter light, helping to reduce extinction. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Let it glow

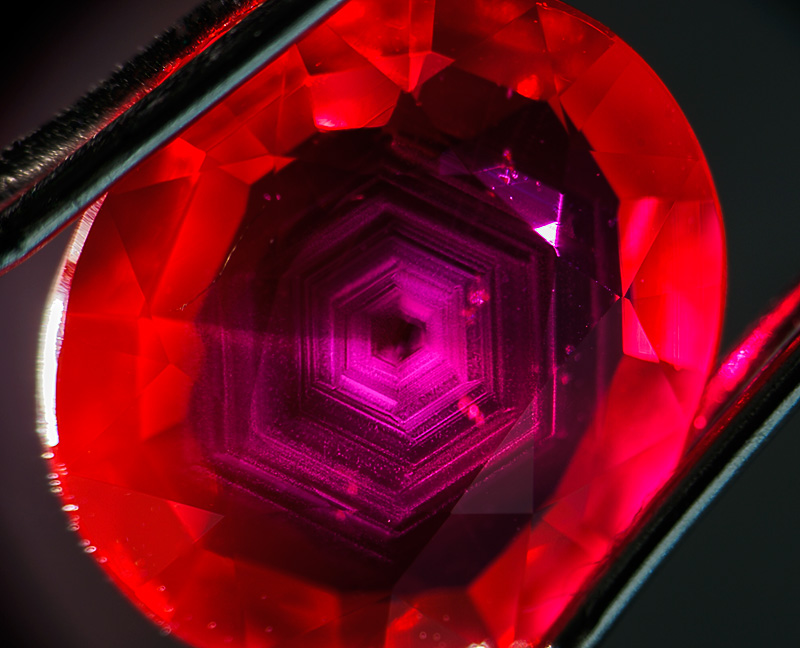

Second, the best stones have high color intensity. This results from a mixture of the slightly bluish red body color and the purer red fluorescent emission.

Due to one of those glorious accidents of nature, ruby has both a red body color and red fluorescence. Furthermore, most rubies will actually fluoresce to visible light. This red fluorescence is one of the keys to a fine ruby's appearance, for it covers up the dark areas of the stone caused by extinction from cutting. Thai/Cambodian rubies possess a purer red body color, [1] but lack the strong fluorescence. In Thai/Cambodian rubies, where light is properly reflected off pavilion facets (brilliance), the color is good. However, where facets are cut too steep, light exits through the side instead of returning to the eye, creating darker areas (extinction). All stones possess this extinction to a certain degree, but in fine Burmese rubies, the strong crimson fluorescence masks it. The best Mogok stones actually glow red and appear as though Mother Nature brushed a broad swath of fluorescent red paint across the face of the stone. This is the carbuncle of the ancients, a term derived from the glowing embers of a fire.

Silk plus fluorescence is a winning combination in ruby. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Silk plus fluorescence is a winning combination in ruby. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

In actuality, rubies from most sources possess strong red fluorescence and silk similar to those from Burma, with the Thai/Cambodian rubies being the exception. However, those from Sri Lanka are generally too pale in color, while with other sources, such as Kenya, Pakistan and Afghanistan, material clean enough for faceting is rare. Thus the combination of fine color (body color plus fluorescence) and facetable material (i.e., internally clean) has put the Burmese ruby squarely atop the crimson mountain. Some old-timers consider Burma to be not just the best source, but the only source of stones fit to be called ruby. When one considers that today probably 90% or more of newly-mined rubies owe a good measure of their clarity and color to heat treatment, this statement does not seem so outlandish (unfortunately, most Burmese rubies are today also heat treated).

|

For the love of a brother Brotherly love knows no bounds, as the following tale shows. When two brothers bought property near Yadanar Kaday Kadar, in Burma's Mogok Stone Tract, their love for each other was so strong they purchased adjoining lots, all the better to visit, raise families together, grow rich together. Alas, Lady Luck doesn't kiss all the boys. While the eldest brother found many fine gems, Brother No. 2, mining just beside him, found nothing. But brotherly love is stronger than any artificial line in the dirt. Seeing his younger brother had found nothing, the properties were exchanged and mining continued. Alas, Lady Luck doesn't kiss all the boys. For the eldest brother, every spade brought forth gems. But his younger brother, mining the same property that had recently yielded such riches, again found nothing. Brotherly sorrow also knows no bounds. Thus Brother No. 1 made the ultimate sacrifice. Not content to merely trade plots., he allowed his brother to mine both pieces of land. Again, his brother found nothing. Lady Luck doesn't kiss all the boys. |

Pigeon's Blood: Chasing the elusive Burmese bird

The Burmese term for ruby is padamya ('plenty of mercury'). Other terms for ruby are derived from the word for the seeds of the pomegranate fruit. [2]

Traditionally, the Burmese have referred to the finest hue of ruby as "pigeon's blood" (ko-twe), a term which may be of Chinese or Arab origin. Witness the following from the Arab, al-Akfani, who described thus the top variety of ruby:

Rummani has the colour of the fresh seed of pomegranate or of a drop of blood (drawn from an artery) on a highly polished silver plate.

— al-Akfani, ca. 1348 AD

Some have compared this color to the center of a live pigeon's eye. Halford-Watkins described it as a rich crimson without trace of blue overtones. Others have defined this still further as the color of the first two drops of blood from the nose of a freshly slain Burmese pigeon. But the pièce de résistance of pigeon's-blood research has to be that of James Nelson, who finally put the question to rest:

In an attempt to seek a more quantitative description for this mysterious red colour known only to hunters and the few fortunate owners of the best Burmese rubies, the author sought the help of the London Zoo. Their Research Department were quick to oblige and sent a specimen of fresh, lysed, aerated, pigeon's blood. A sample was promptly spectrophotometered…. The Burmese bird can at last be safely removed from the realms of gemmology and consigned back to ornithology.

— James B. Nelson, 1985, Journal of Gemmology

After that, the only question remaining is whether or not "spectrophotometered" is a genuine English verb.

Color preferences do change with time. The preferred color today is not necessarily that of a hundred, or even fifty years ago. In my experience, the color most coveted today is that akin to a red traffic signal or stoplight. It is a glowing red color, due to the strong red fluorescence of Burmese rubies, and is unequalled elsewhere in the world of gemstones. Thai/Cambodian rubies may possess a purer red body color, but the lack of red fluorescence and silk leaves them dull by comparison. It must be stressed that the true pigeon's-blood red is extremely rare, more a color of the mind than the material world. One Burmese trader expressed it best when he said: "…asking to see the pigeon's blood is like asking to see the face of God."

The second-best color in Burma is termed "rabbit's blood," or yeong-twe. It is a slightly darker, more bluish red. Third best is a deep hot pink termed bho-kyaik. This was the favorite color of the famous Mogok gem dealer, A.C.D. Pain. The literal meaning of bho-kyaik is "preference of the British."

Fourth-best is a light pink color termed leh-kow-seet (literally 'bracelet-quality' ruby). At the bottom of the ruby scale is the dark red color termed ka-la-ngoh. This has an interesting derivation for it means literally either "crying-Indian quality" or "even an Indian would cry," so termed because it was even darker than an Indian's skin. Most dark rubies were sold in Bombay or Madras, India. Ka-la-ngoh stones were said to be so dark that even Indians would cry out in despair when confronted with this quality.

Pondering ruby in the Mogok Stone Tract's Kyatpyin valley. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Pondering ruby in the Mogok Stone Tract's Kyatpyin valley. Photo: R.W. Hughes

Mogok: Looking ahead

What is it that draws us to ruby? Daw Nann Gyi Taung, above Burma's valley of rubies, is perhaps a fitting place to sit and ponder that question. For hundreds of years, the finest rubies the earth has ever seen have been taken from the soil beneath this mountain. Countless fortunes have been made, but for some, the crimson stones have brought only grief.

In upcountry Burma, tin roofs are a sign of prosperity. Below Daw Nann Gyi Taung, a veritable carpet of tin sprawls across the valley. As I gaze into that valley, and across the jungled hills of the Shan State, thunderheads build on the horizon, signaling the beginning of yet another storm. Before long, the heavens are hammering out a steady rat-a-tat-tat drumbeat on the valley's tin roofs. Once again, it is raining in Rubyland. And everything is fine. For the first time in many decades, tomorrow looks better than today.

What is it that draws us to ruby? Like so many others seekers before me, I had come to this remote valley looking for the red stone, trying to get a little closer to this magnificent gem, perhaps to find an answer to that question. And it was this that was on my mind as the rain pounded down around me and I climbed down off Daw Nann Gyi Taung, deep in thought. Then, something caught my eye. The rain had just uncovered a flash of crimson. And in that one instant I found my answer. There on the ground before me lay a tiny fragment – all of creation bundled up into one tiny pebble. I was home. My pilgrimage was at an end. I had just seen the face of God.

About the author

Richard W. Hughes is one of the world’s foremost experts on ruby and sapphire. The author of many books and over 170 articles, his writings and photographs have appeared in a diverse range of publications, and he has received numerous industry awards. Co-winner of the 2004 Edward J. Gübelin Most Valuable Article Award from Gems & Gemology magazine, the following year he was awarded a Richard T. Liddicoat Journalism Award from the American Gem Society. In 2010, he received the Antonio C. Bonanno Award for Excellence in Gemology from the Accredited Gemologists Association. The Association Française de Gemmologie (AFG) in 2013 named Richard as one of the Fifty most important figures that have shaped the history of gems since antiquity. In 2016, Richard was awarded a visiting professorship at Shanghai's Tongji University. 2017 saw the publication of Richard and his wife and daughter's Ruby & Sapphire • A Gemologist's Guide, arguably the most complete book ever published on a single gem species and the culmination of four decades of work in gemology. In 2018, Richard was named Photographer of the Year by the Gem-A, recognizing his photo of a jade-trading market in China, while in 2020, he was elected to the board of directors of the Accredited Gemologists Association and was appointed to the editorial review board of Gems & Gemology and The Australian Gemmologist magazine. In 2022, Richard published Jade • A Gemologist's Guide, while 2024 brought Broken Bangle • The Blunder-Besmirched History of Jade Nomenclature. His jade trilogy was completed in 2025 with his translation of Heinrich Fischer's Nephrite and Jadeite.

Footnotes

1 Purer in the sense that the hue position is closer to the center of the red (relative to purple and orange). [return to article]

2 The Thai word for ruby, taubptim, also means pomegranate. [return to article]

Further reading

- Burmese Sapphire Giants

- Where the Twain Do Meet: Thailand's Border Towns

- Ruby & Sapphire –The Book: World Sources – Burma

Note

After dreaming about it for years, in April 1996 I finally made it to Mogok and this piece was the result. It was first published in Colored Stone (1996: Renaissance in Rubyland, Vol. 9, No. 6, Nov.-Dec., pp. 29–33) and Momentum magazines (1996, Vol. 4, No. 13, Dec. 1996–Feb. 1997, pp. 18–21). Additional illustrations have been added to this web version.

References

- Akfani (1908) [Treatise on precious stones], translated by P.L. Cheikho. Al-Machriq, Vol. 11, pp. 751–765.

- Atlay, F. and Morgan, A.H. (1905) The Burma Ruby Mines. London, The Burma Ruby Mines, Limited, pamphlet with map and photos.

- Halford-Watkins, J.F. (2012) The Book of Ruby and Sapphire. Hong Kong, RWH Publishing, [from a 1934 manuscript], 434 pp.

- Nelson, J.B. (1986) The colour bar in the gemstone industry. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 20, No. 4, Oct., pp. 217–237.