Why should Hugh Hefner be the only one to enjoy twins? This special Hyperion Inclusion Gallery features images from the Lotus Gemology Hyperion Inclusion Database, but are shown as pairs, all the better to compare one form of beauty with another.

It would be both an identical work of art only by virtue of its difference.

The same but different, he suggested, like twins.

Johnny Rich, The Human Script

Click on any photo for a larger image.

|

|

|

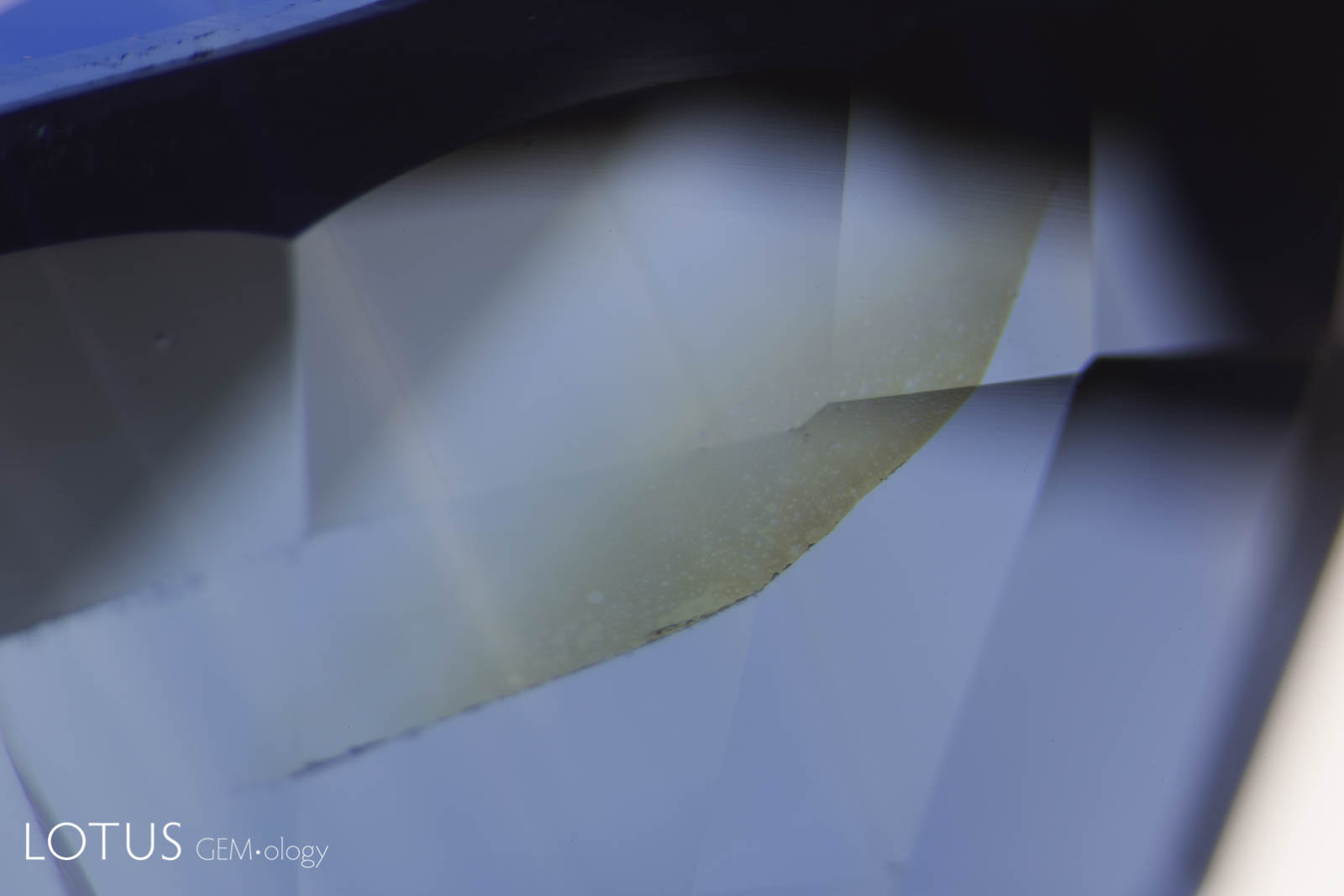

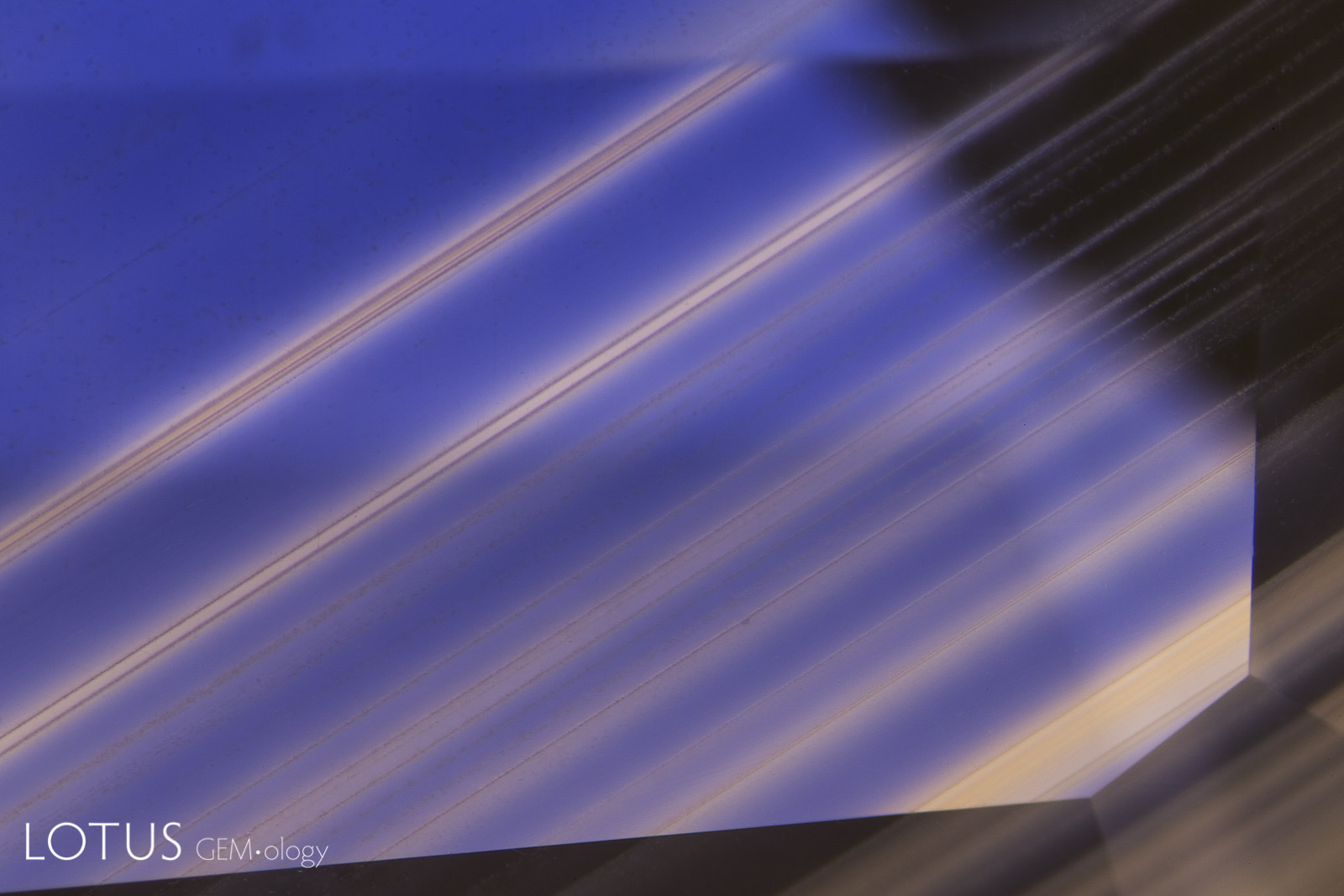

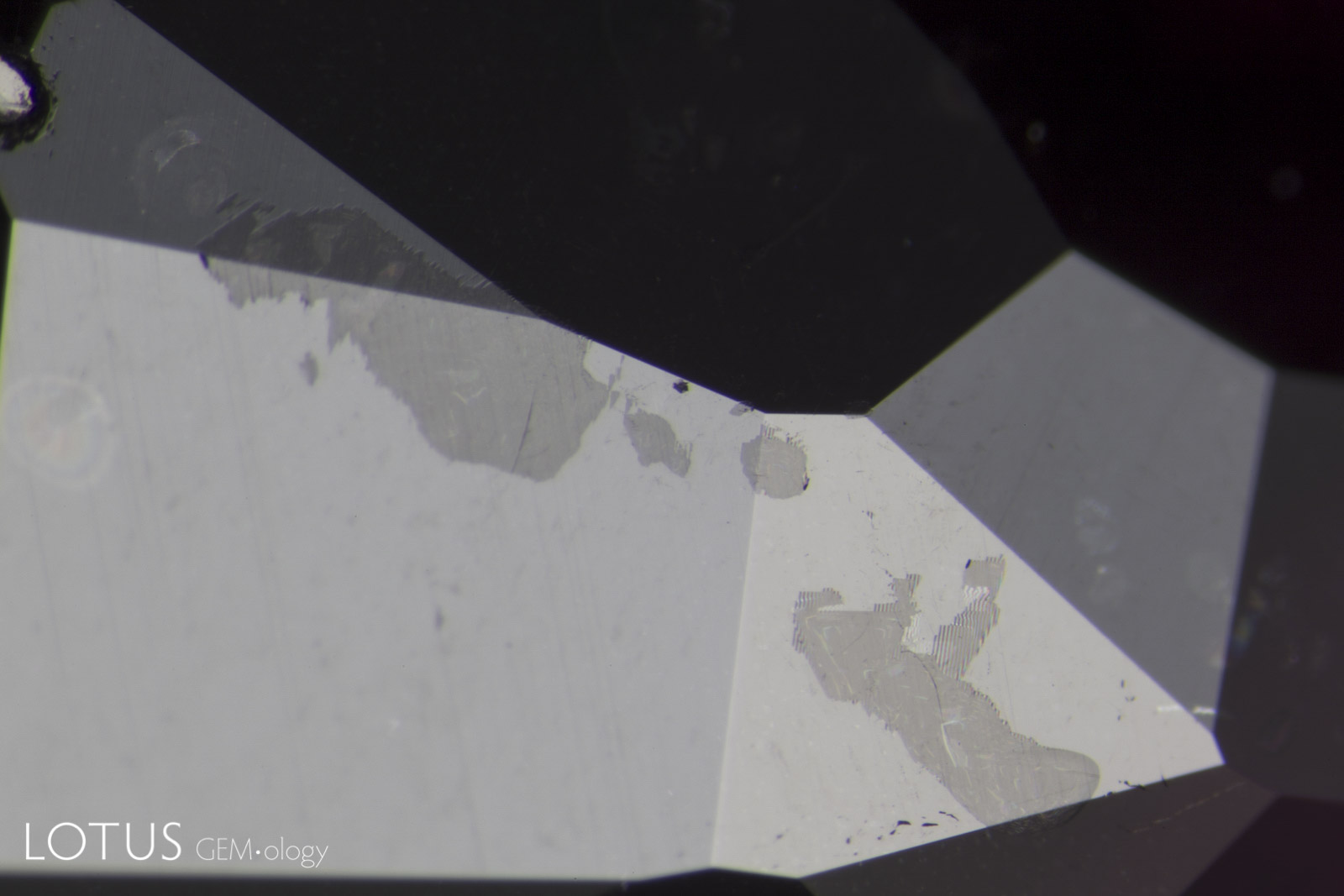

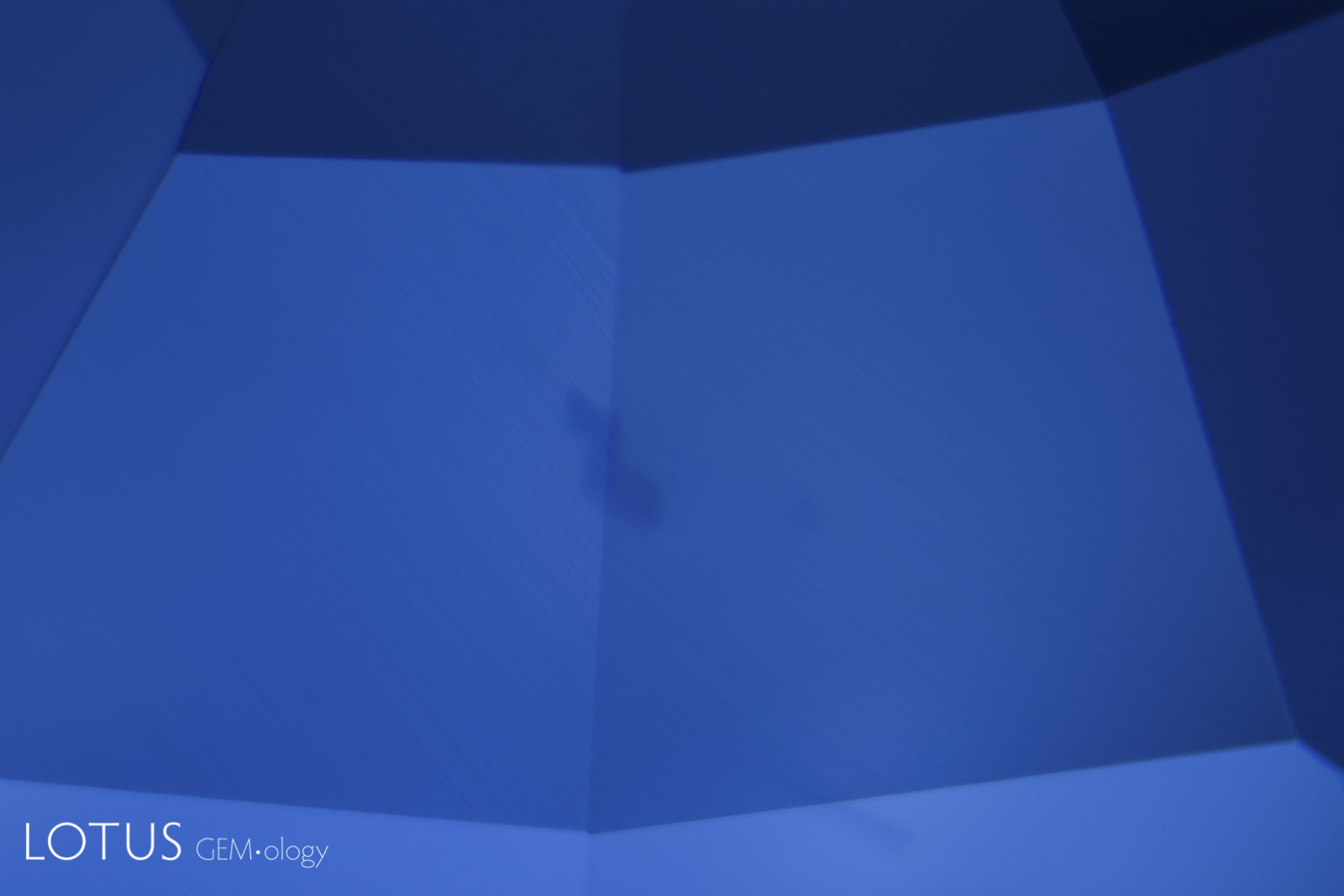

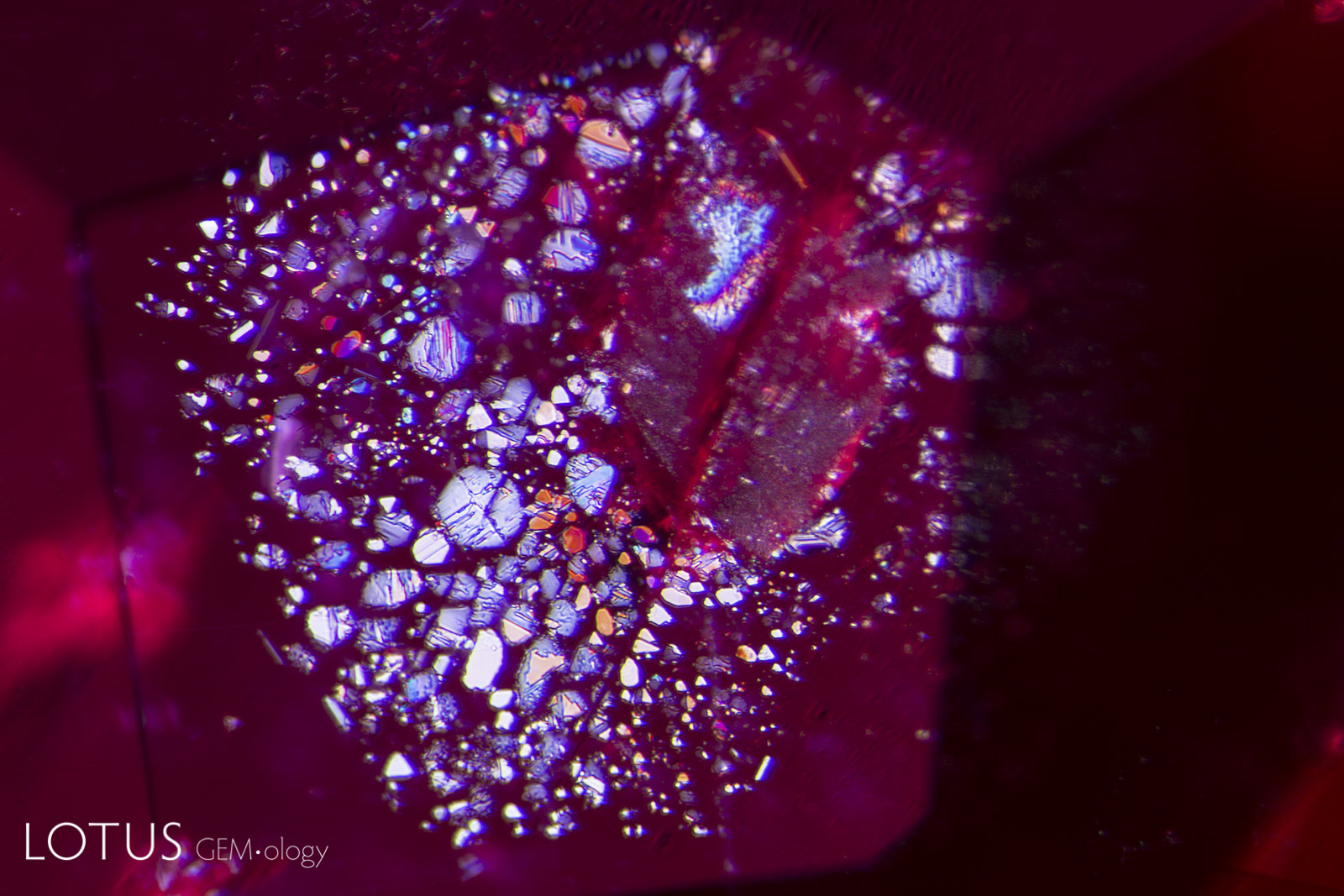

Left: The first step of preparing a piece of fei cui jade for polymer impregnation is to boil it in acid to remove any mineral impurities from the tiny fissures between the individual crystal grains that make up the jade rock. These fissures are then filled with a polymer. Thus the treatment removes brown discoloration and greatly improves the translucency. However the telltale micro-fissures from the bleaching process can still be seen by examining the surface with overhead light, as shown here. Polymer-impregnated jade is termed “B-jade” in the trade. Untreated jade is known as “A-jade,” while dyed jade is “C-jade.” If a dyed polymer is used, it is termed “B+C jade.” Field of View = 12 mm. |

|

|

|

|

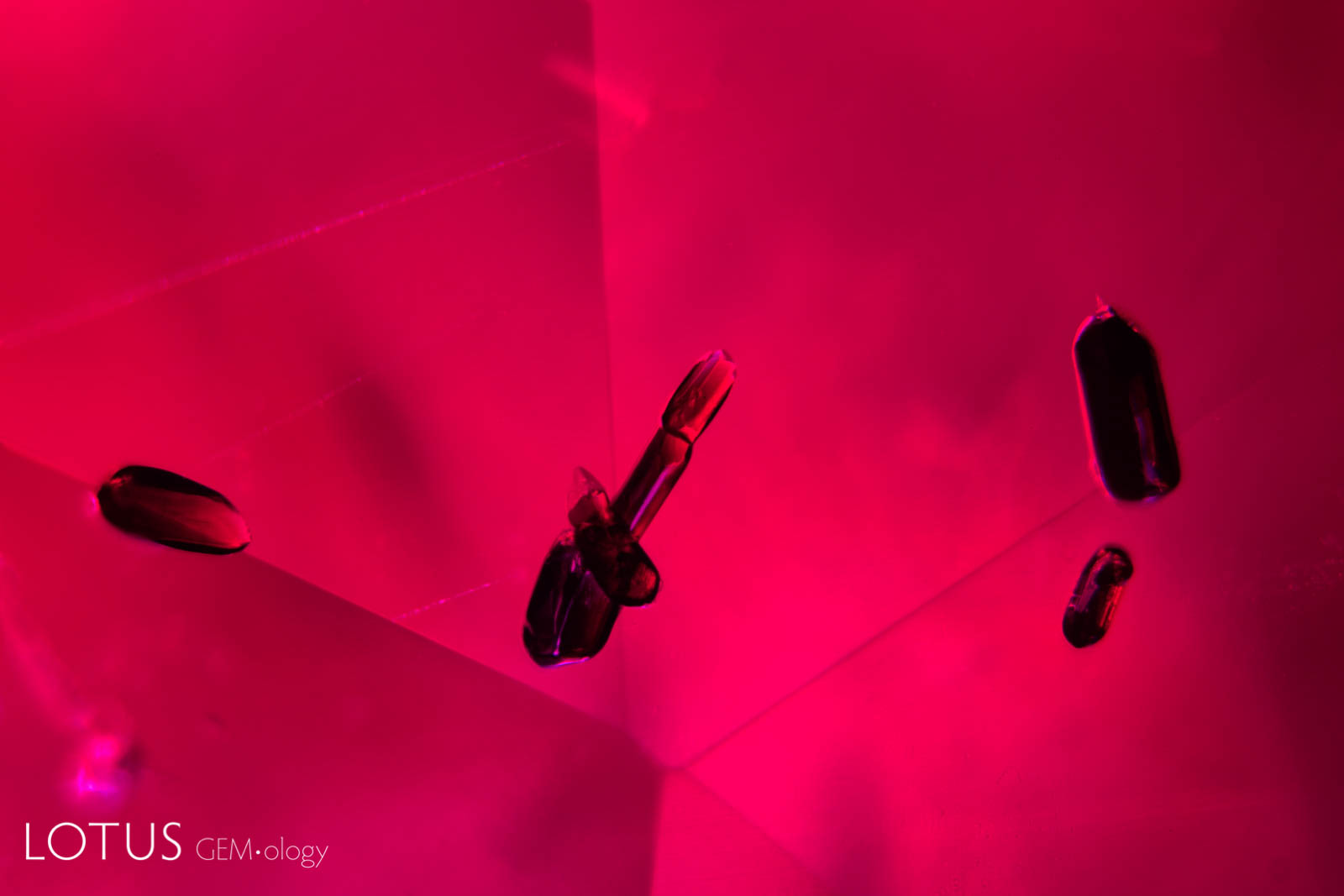

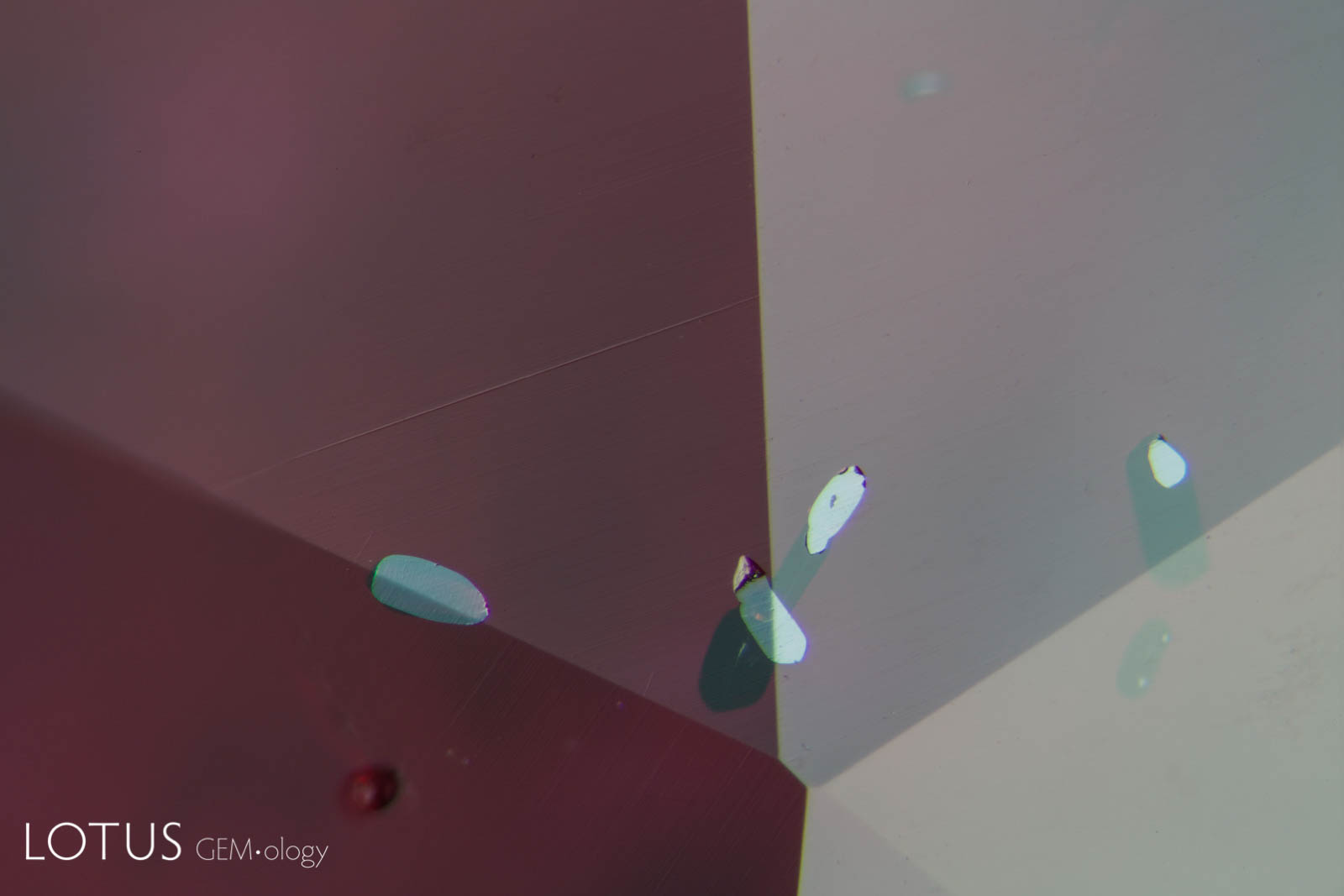

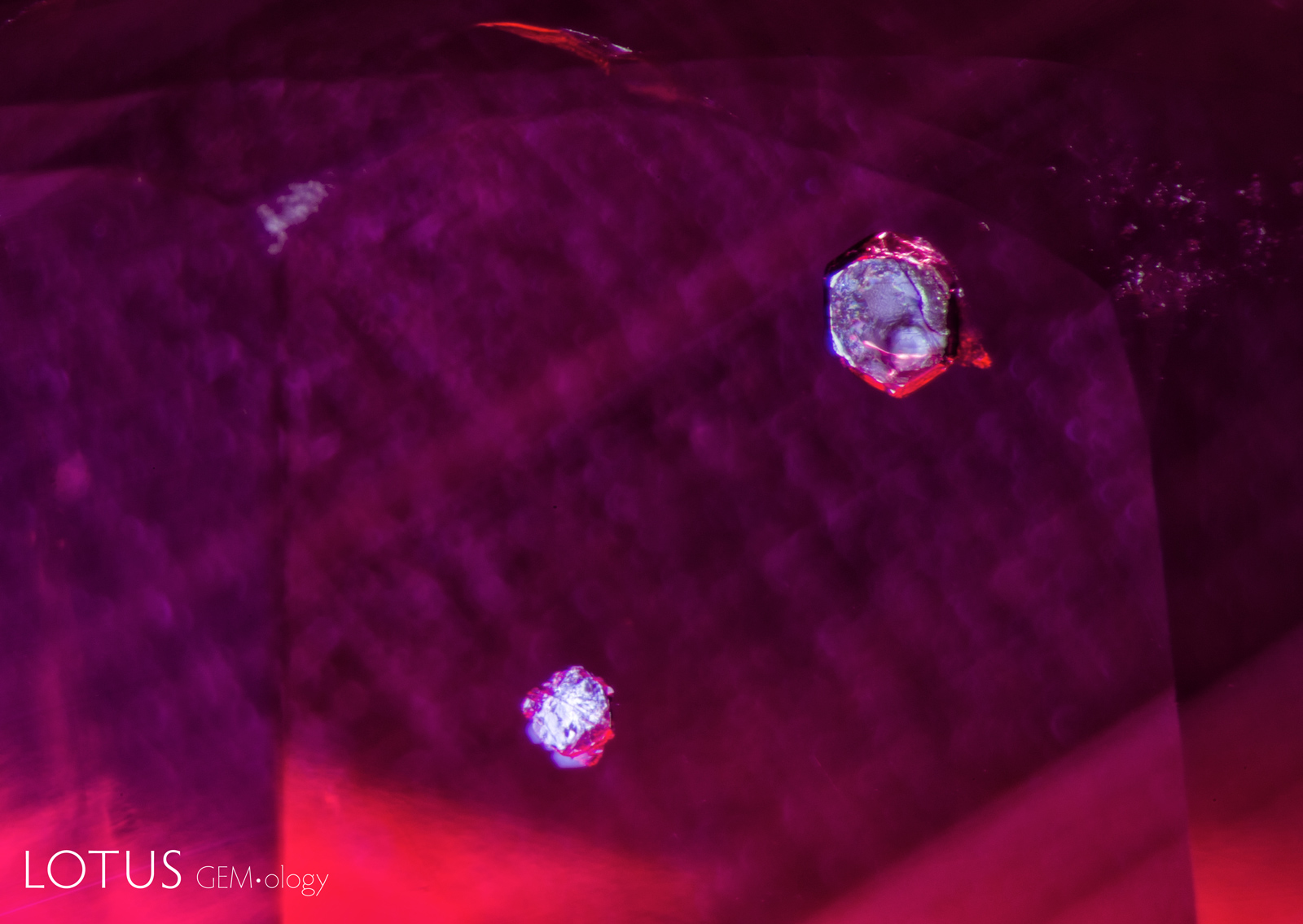

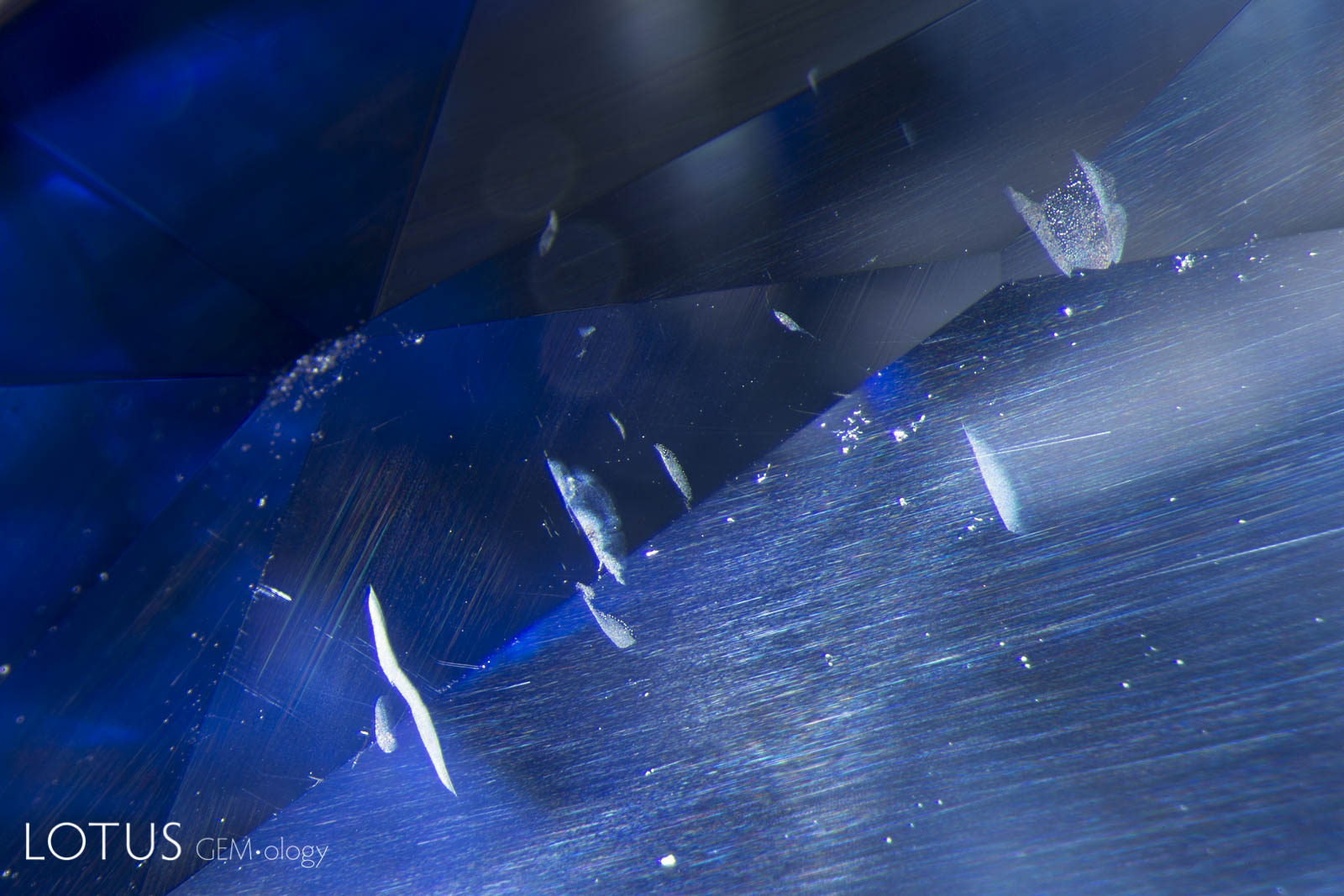

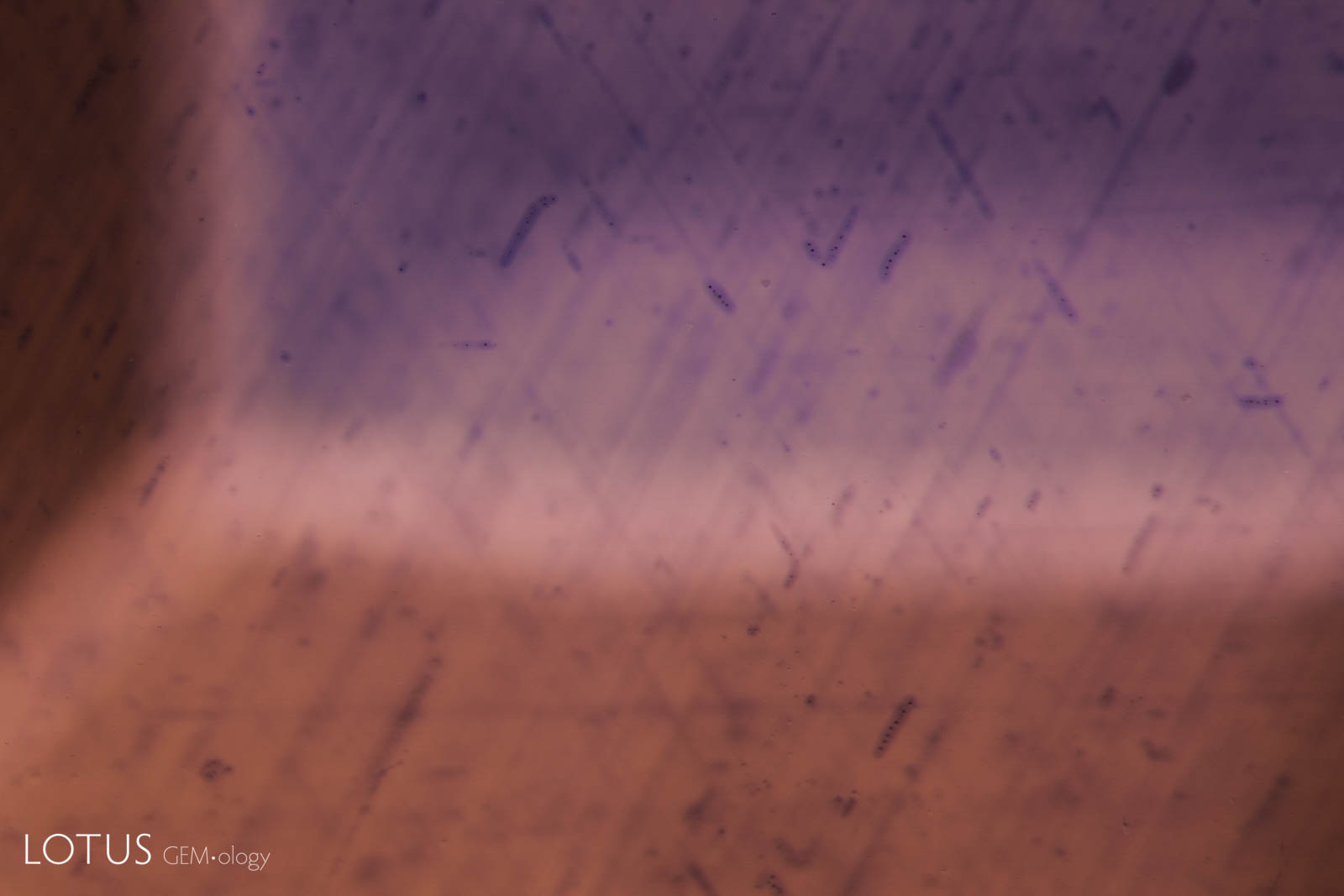

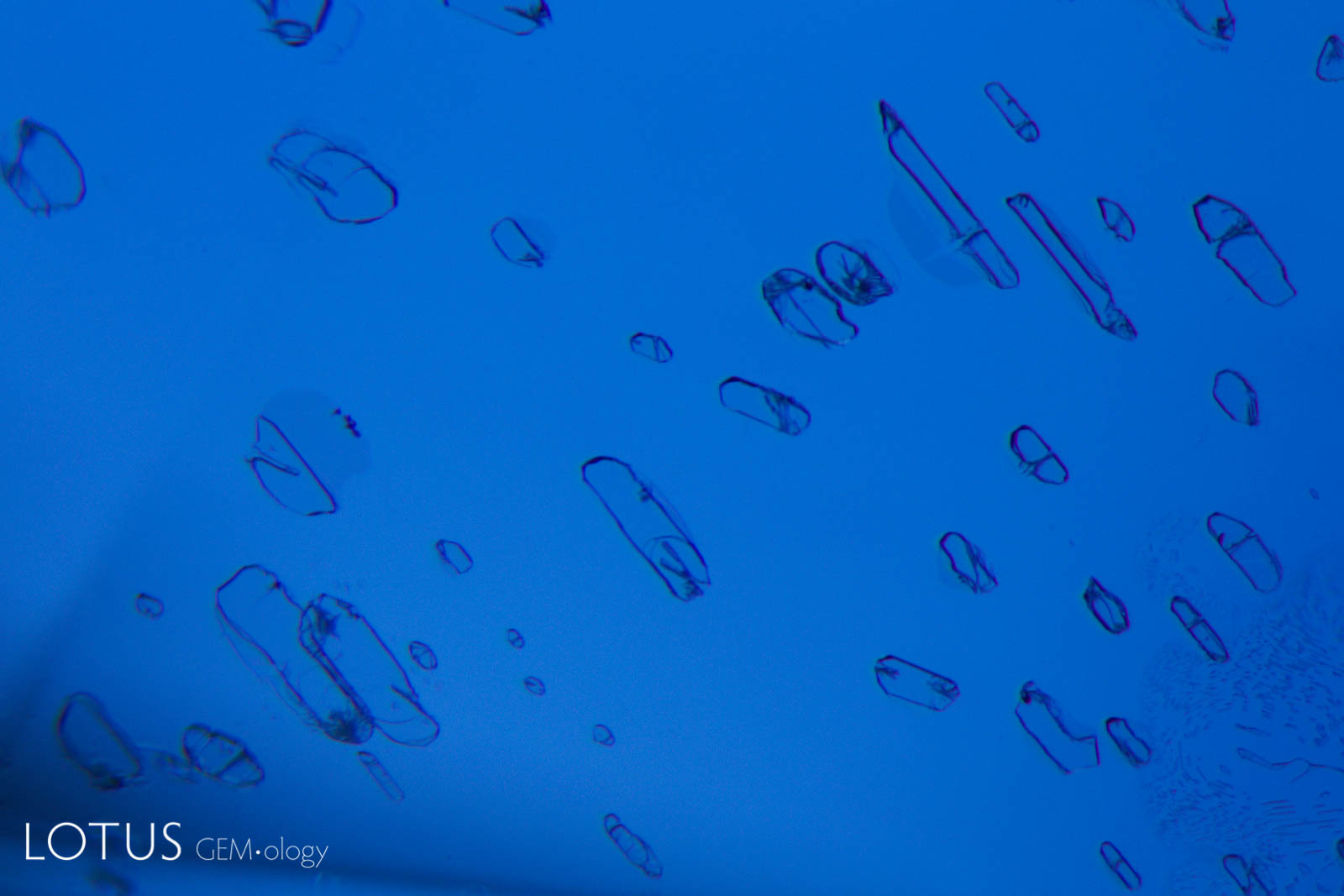

Left: These included hexagonal crystals in a Sri Lankan blue sapphire have inclusions of their own. These are actually sapphire crystals captured in a sapphire host, as shown by their extremely low relief. Because of the low relief, the outlines of the crystals are difficult to discern. |

|

|

|

|

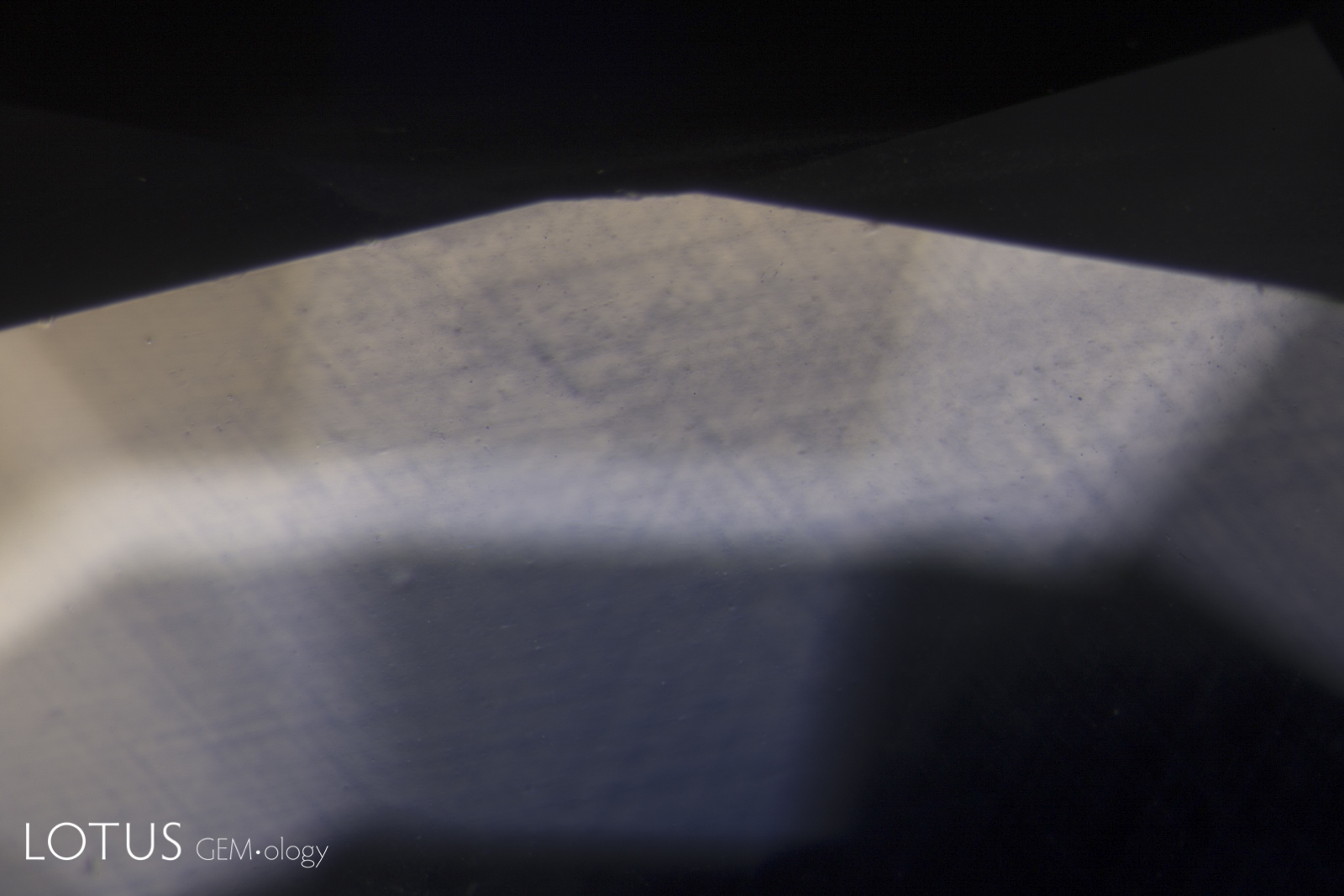

Left: Another example of sapphire crystal included in a Ceylon sapphire, this time a yellow sapphire. In darkfield the outline of the sapphire crystal is hard to discern. |

|

|

|

|

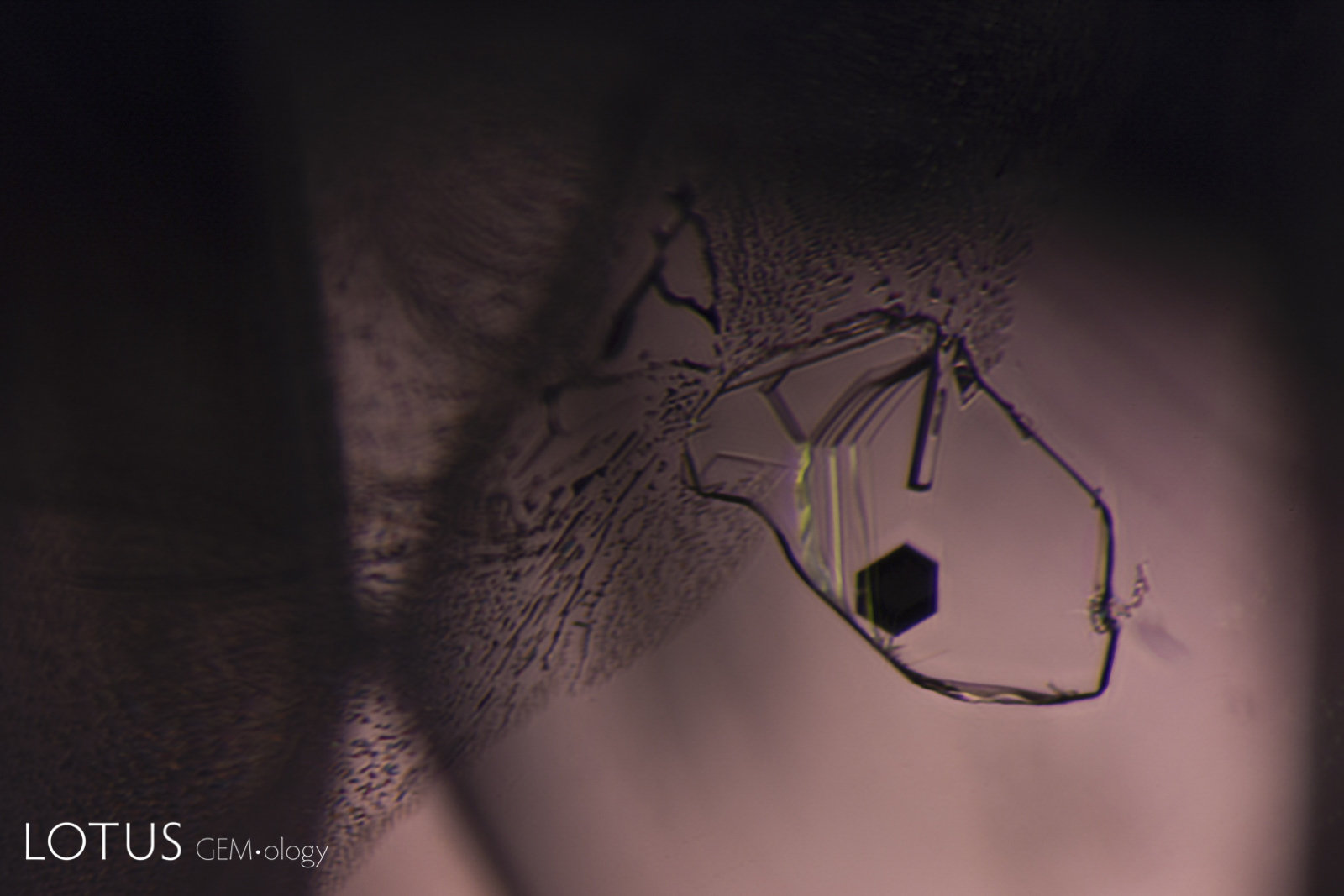

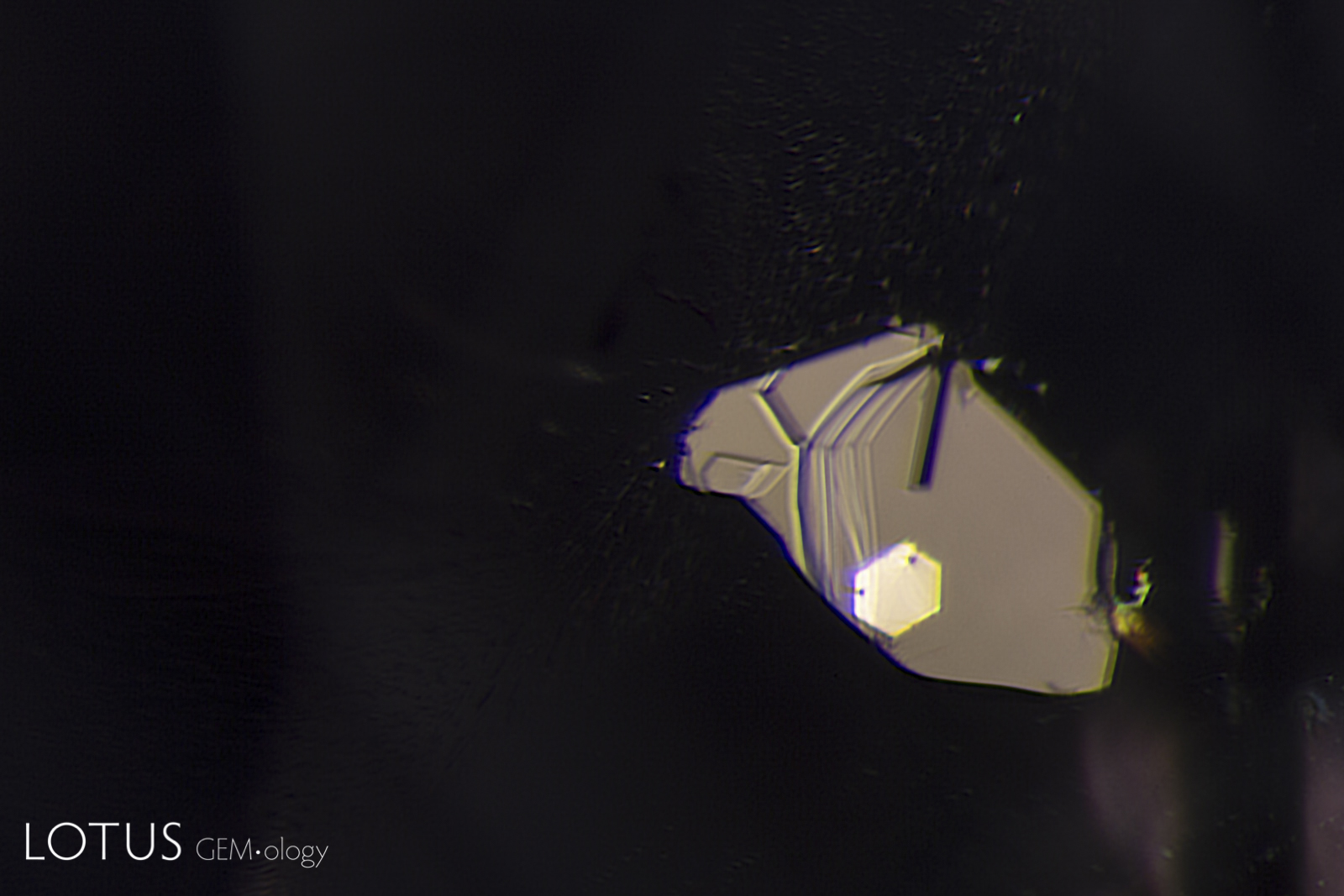

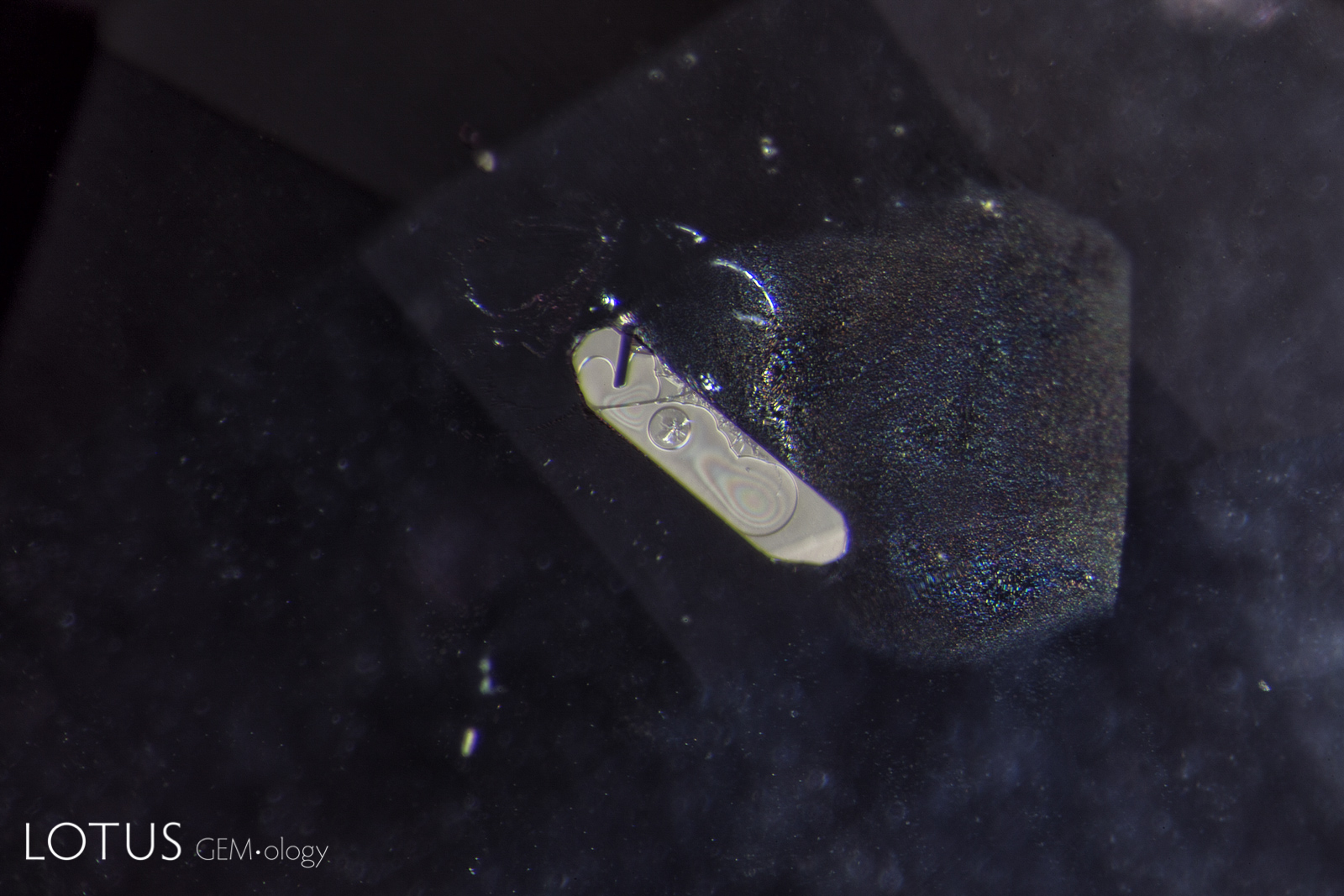

Left: When viewed in transmitted light, this negative crystal within an untreated Sri Lanka padparadscha displays a hexagonal plate of graphite, along with a needle of diaspore. The undamaged nature of the negative crystal and diaspore needle confirms that the gem has not been heat treated. |

|

|

|

|

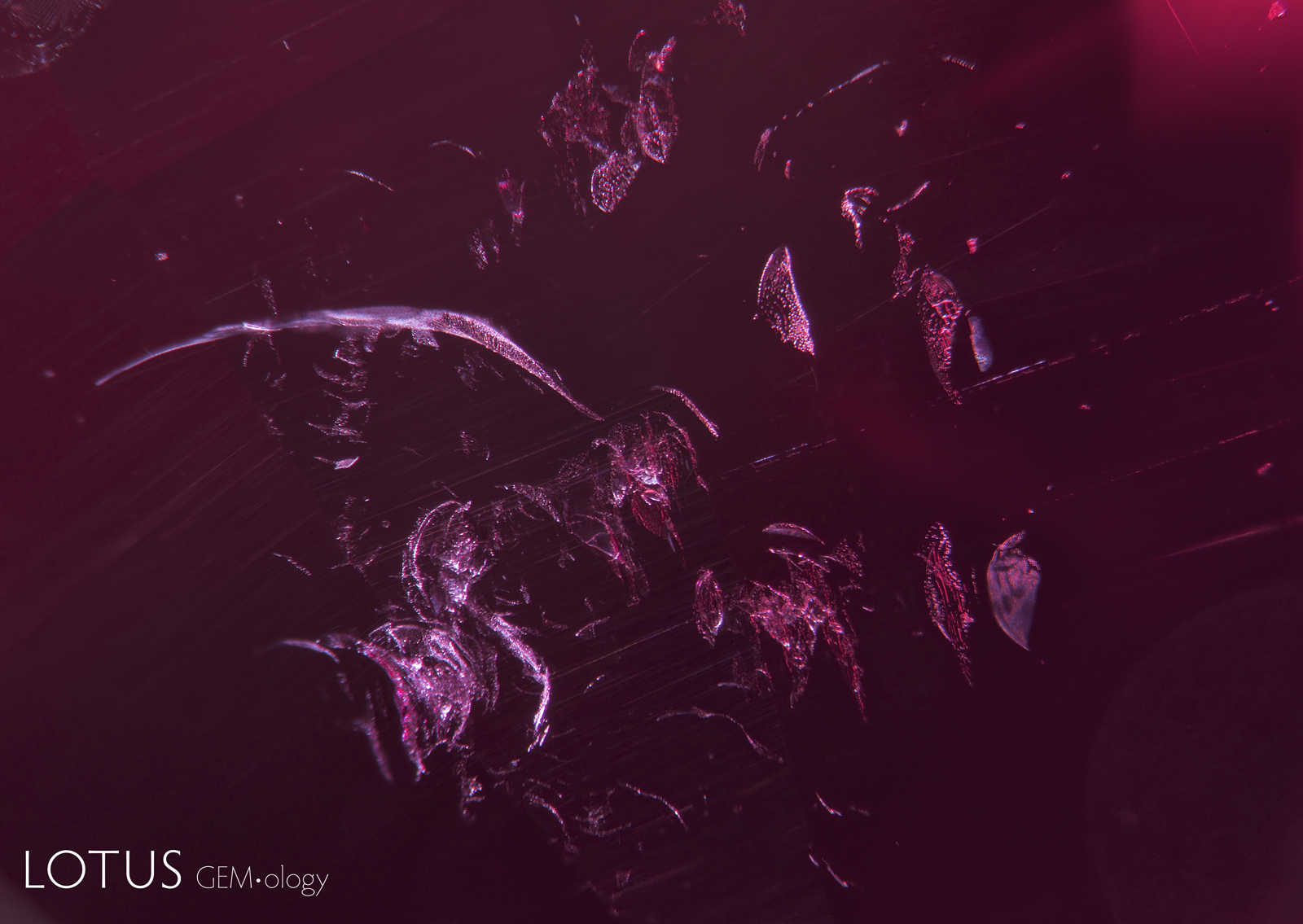

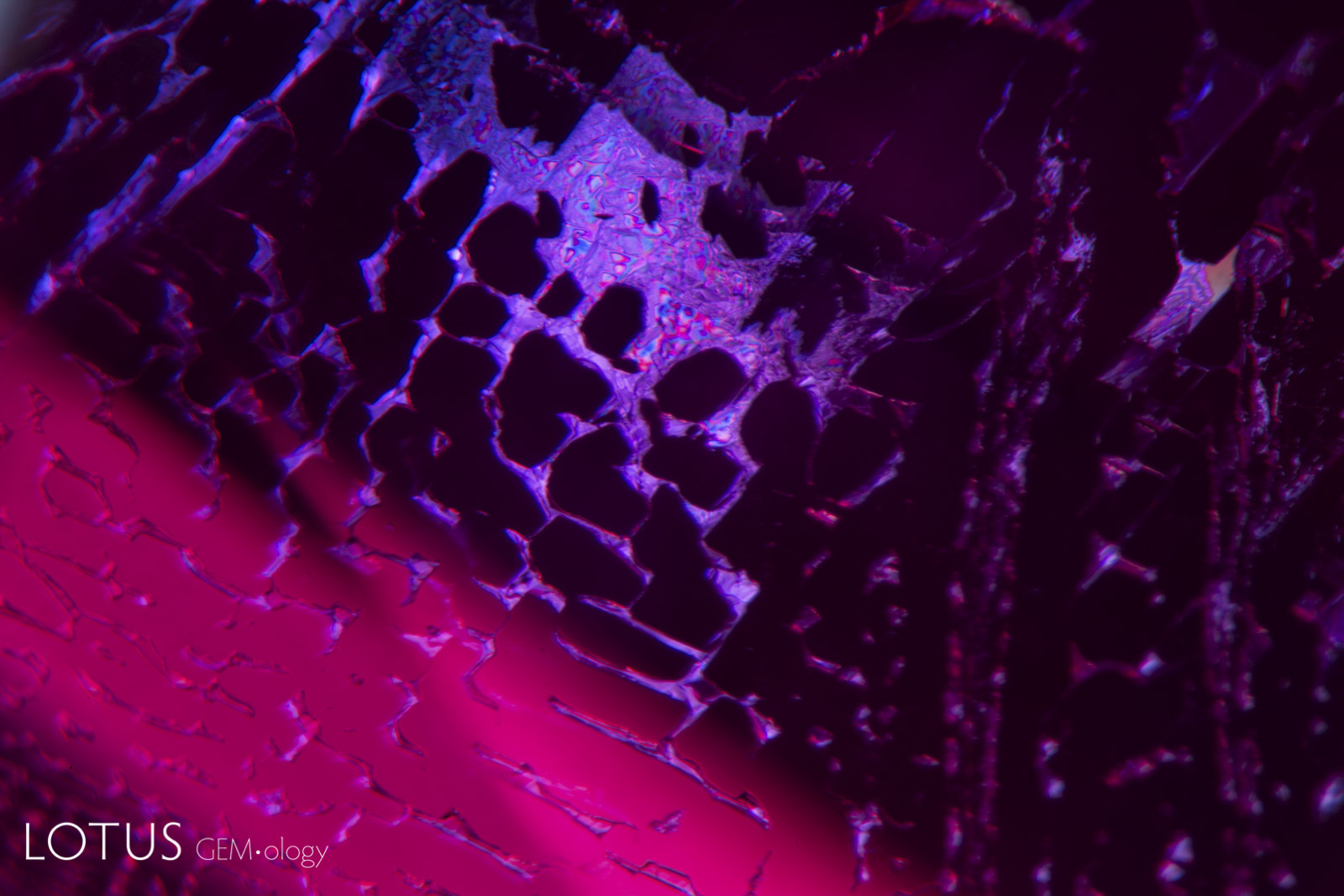

Left: This red spinel from Tanzania’s Mahenge mines showed an unusual orange coloration surrounding a fingerprint inclusion. |

|

|

|

|

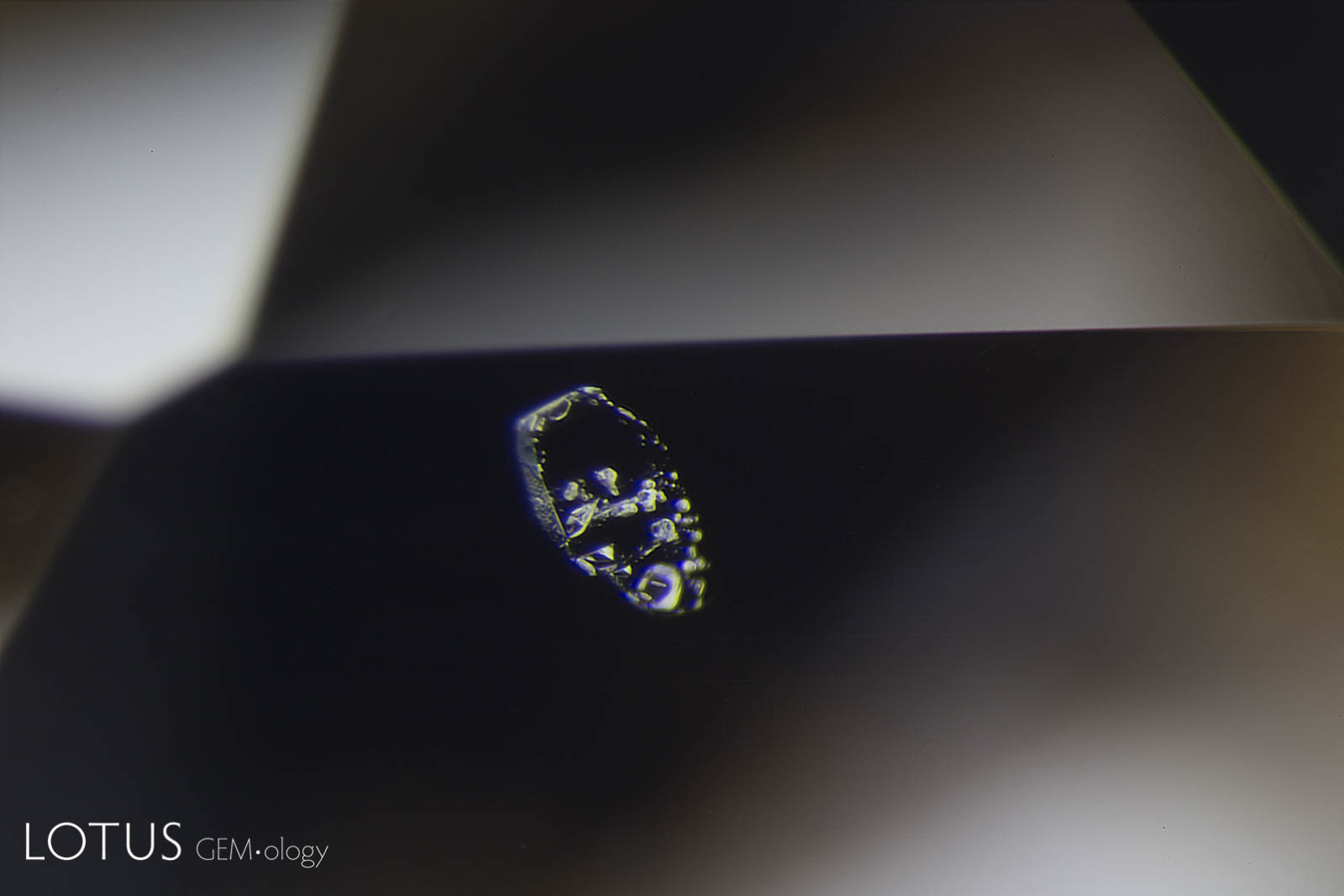

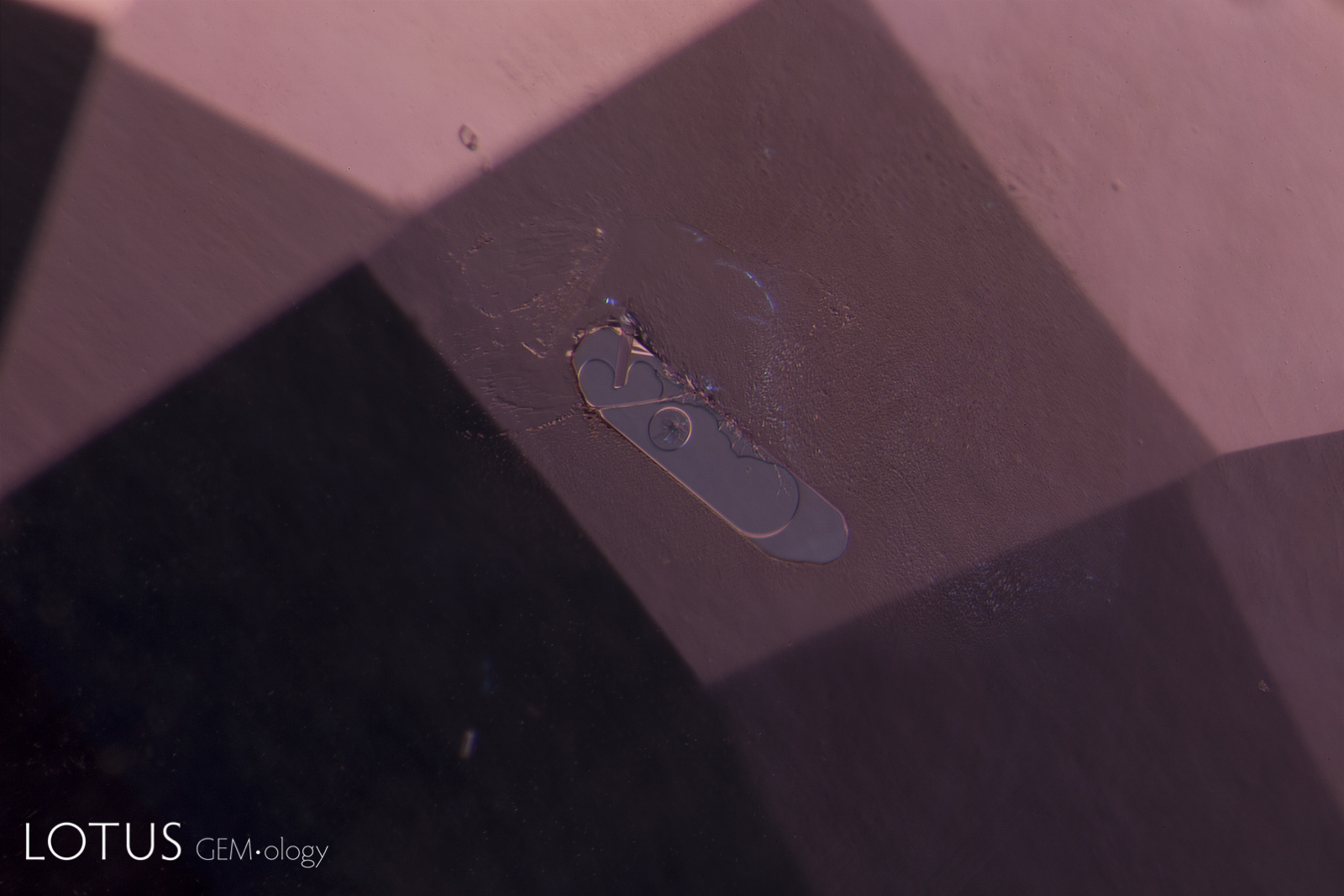

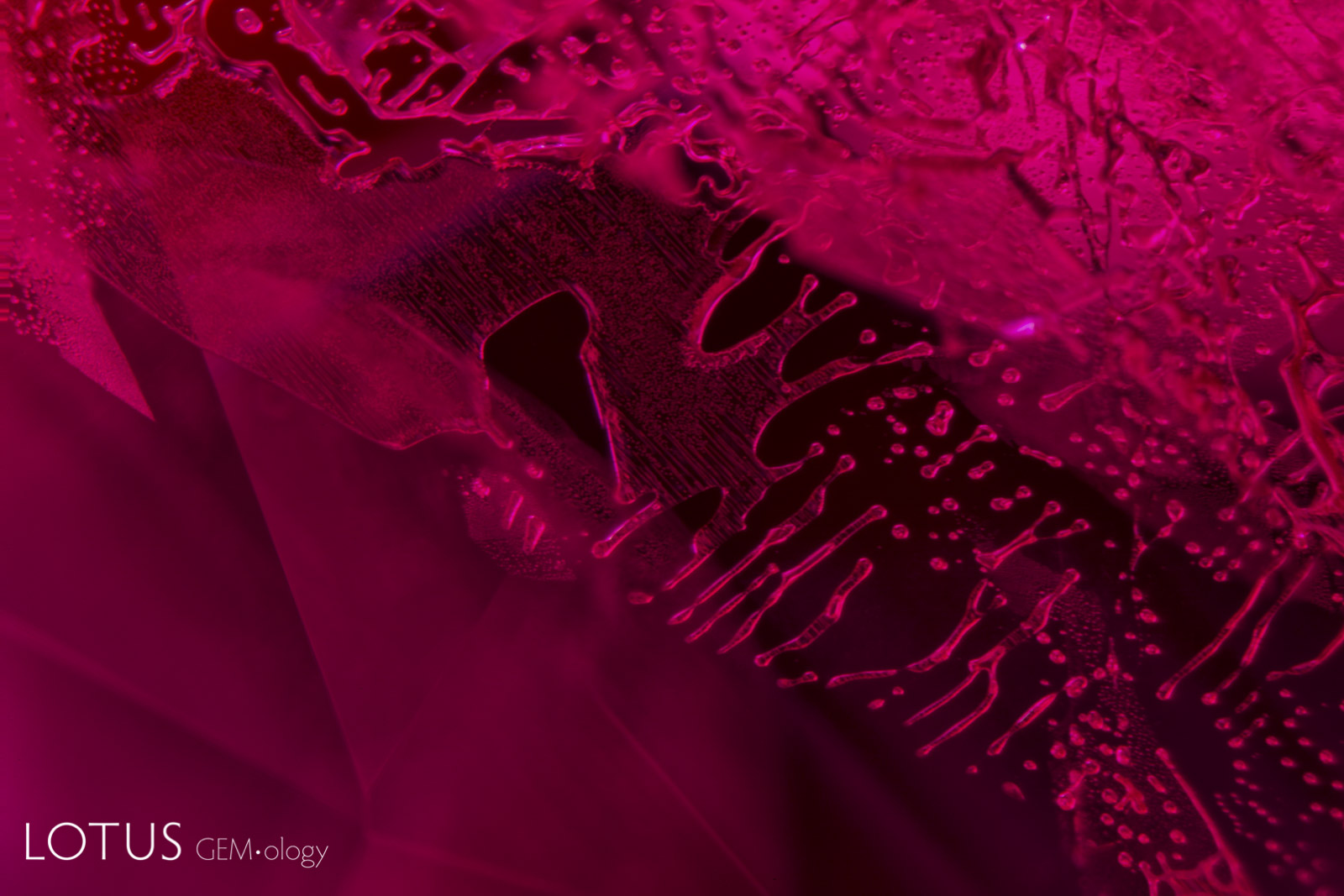

Left: In this heated and fissure-healed ruby from Myanmar, a surface cavity is filled with glass. The glass can be identified by the gas bubble at the lower part of the cavity. |

|

|

|

|

Left: Demonstrating that the inner world can be as captivating as that outside, this Madagascar sapphire displays a small fingerprint scar with a beguiling moiré pattern. The undamaged nature of this inclusion testifies to the natural, untreated origin of the gem. Photo: E. Billie Hughes |

|

|

|

|

Left: Many Mozambique rubies contain mica crystals, which are extremely heat sensitive and will be damaged by heat treatment, even at relatively low temperatures (800–1000°C). Unheated Mozambique ruby. |

|

|

|

|

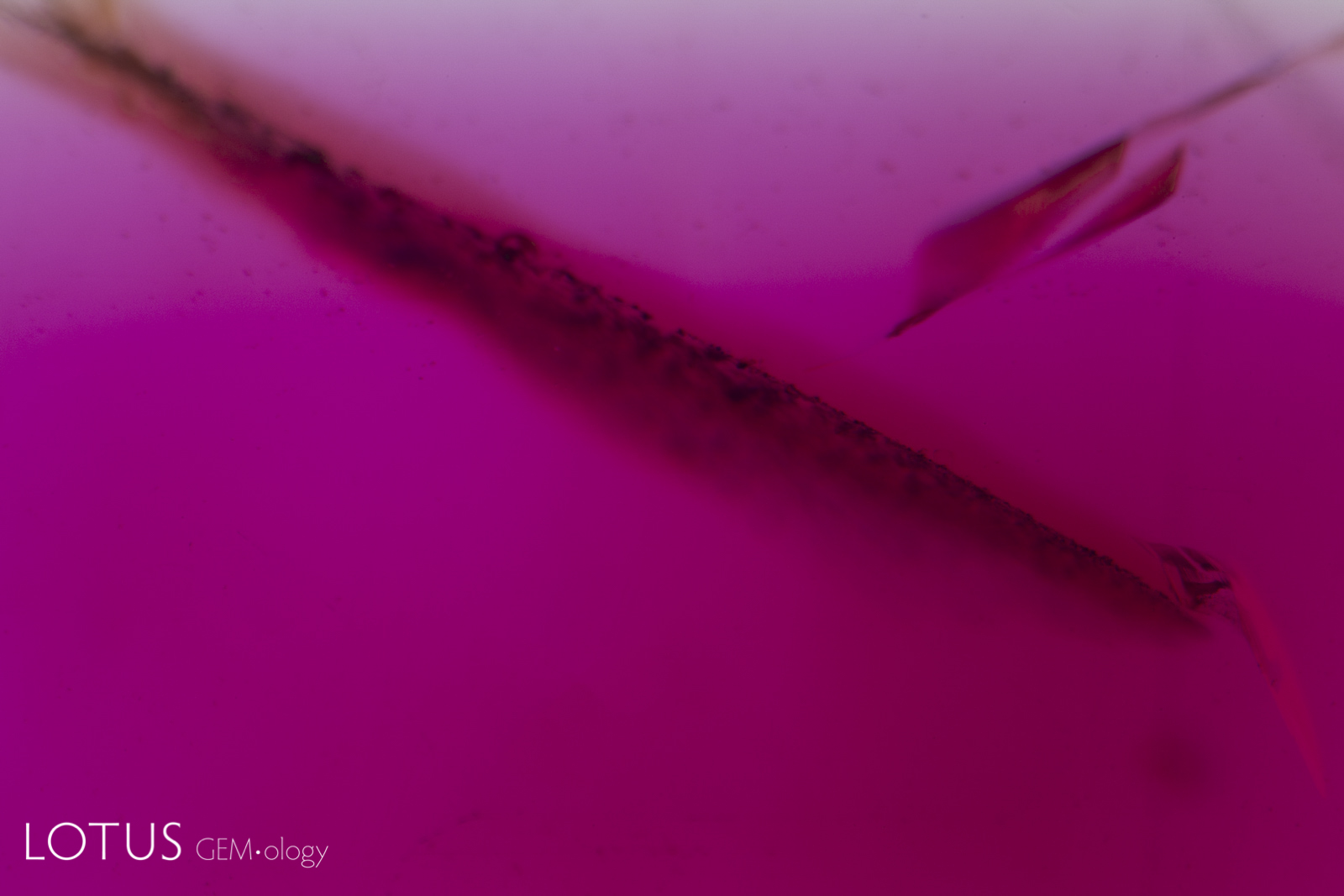

Left: Many crystals contain shallow fissures on their surfaces. In sapphires from Sri Lanka, Myanmar and Madagascar, these fissures often contain epigenetic yellow stains caused by deposits from Fe-rich fluids. |

|

|

|

|

Left: Many rubies and sapphires contain shallow fissures on their surfaces. These typically display yellow to orange epigenetic iron oxide stains, as shown here. Unheated Mozambique ruby. |

|

|

|

|

Left: This image clearly illustrates what master photomicrographer John Koivula has termed “chromophore cannibalization.” As titanium is drawn out of solid solution to form exsolved rutile silk, the area in the immediate vicinity is decolorized, losing its blue color. This is a natural process and is the reverse of “internal diffusion,” where heat treatment sends the titanium back into solution, creating blue clouds or “inkspots” around the rutile remnants. Photo: E. Billie Hughes |

|

|

|

|

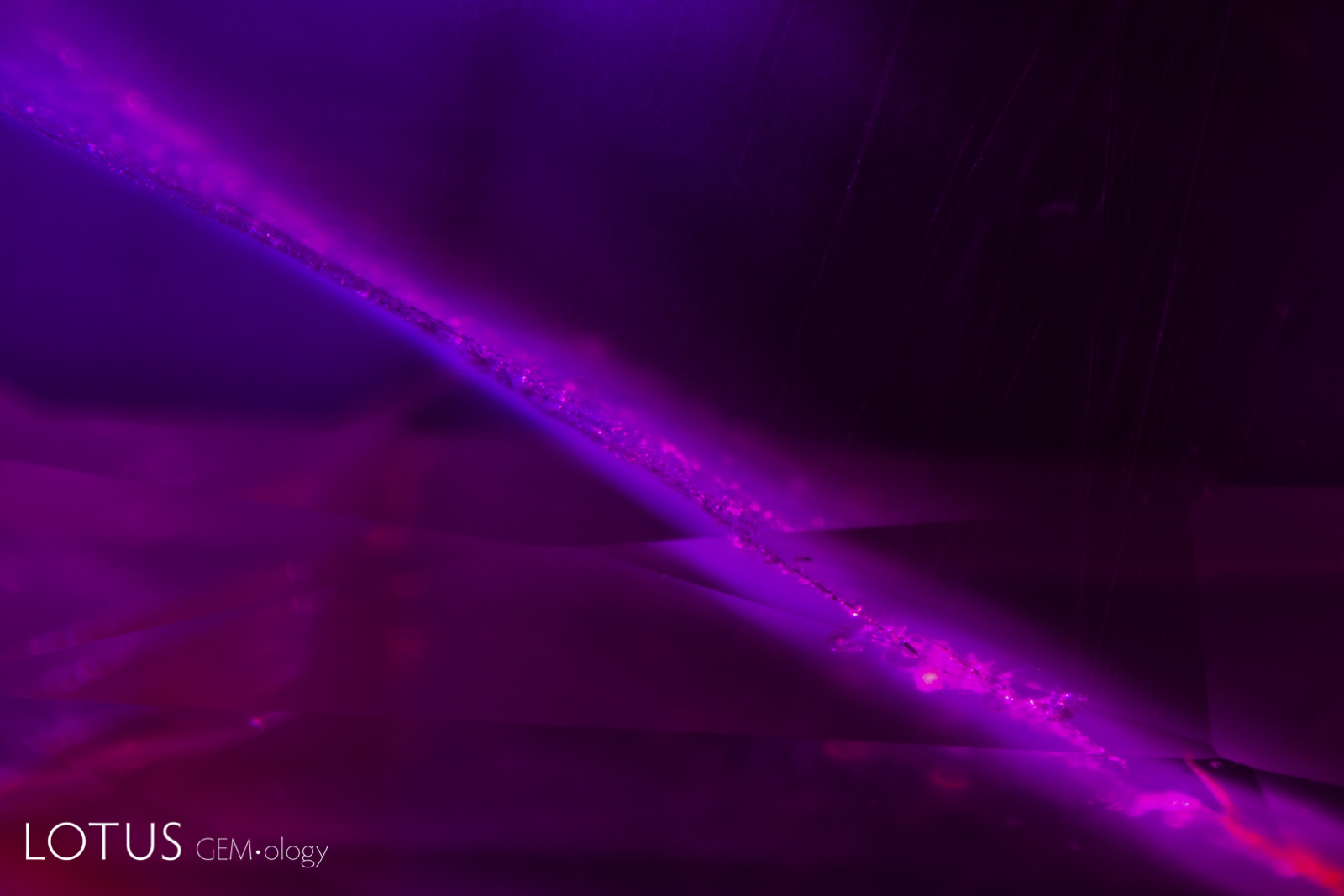

Left: In this heated sapphire, one can clearly see “ink spot” internal diffusion, caused when the heat treatment partially dissolves the rutile silk, sending titanium into solid solution. This is a sure sign of high-temperature heat treatment. Check the next photo for the appearance in short-wave ultraviolet light. Photo: Richard W. Hughes |

|

|

|

|

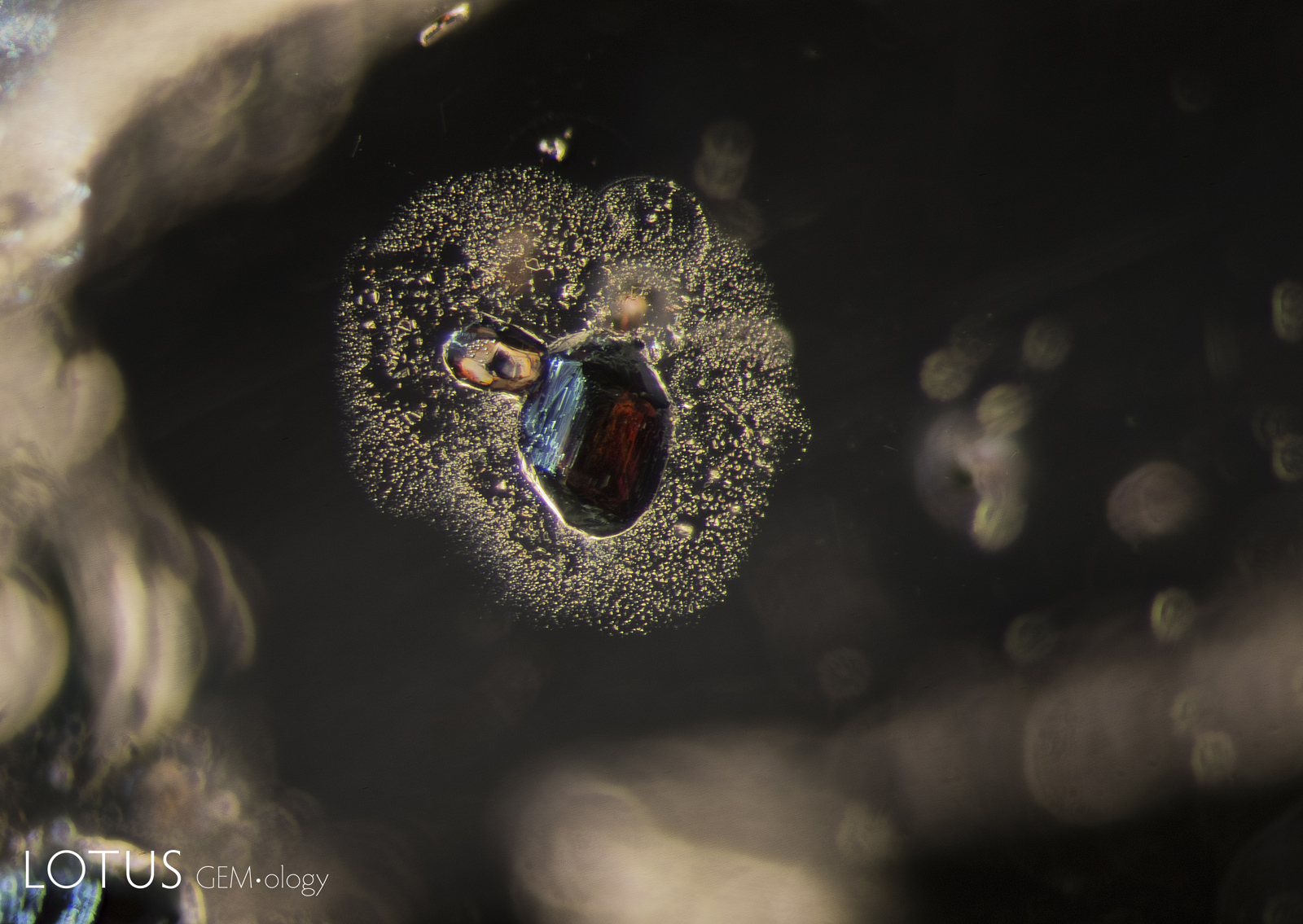

Left: Dark red, high relief crystal of primary rutile; surrounded by halo of fine particles; unheated sapphire, Songea, Tanzania; Darkfield + oblique fiber optic illumination. |

|

|

|

|

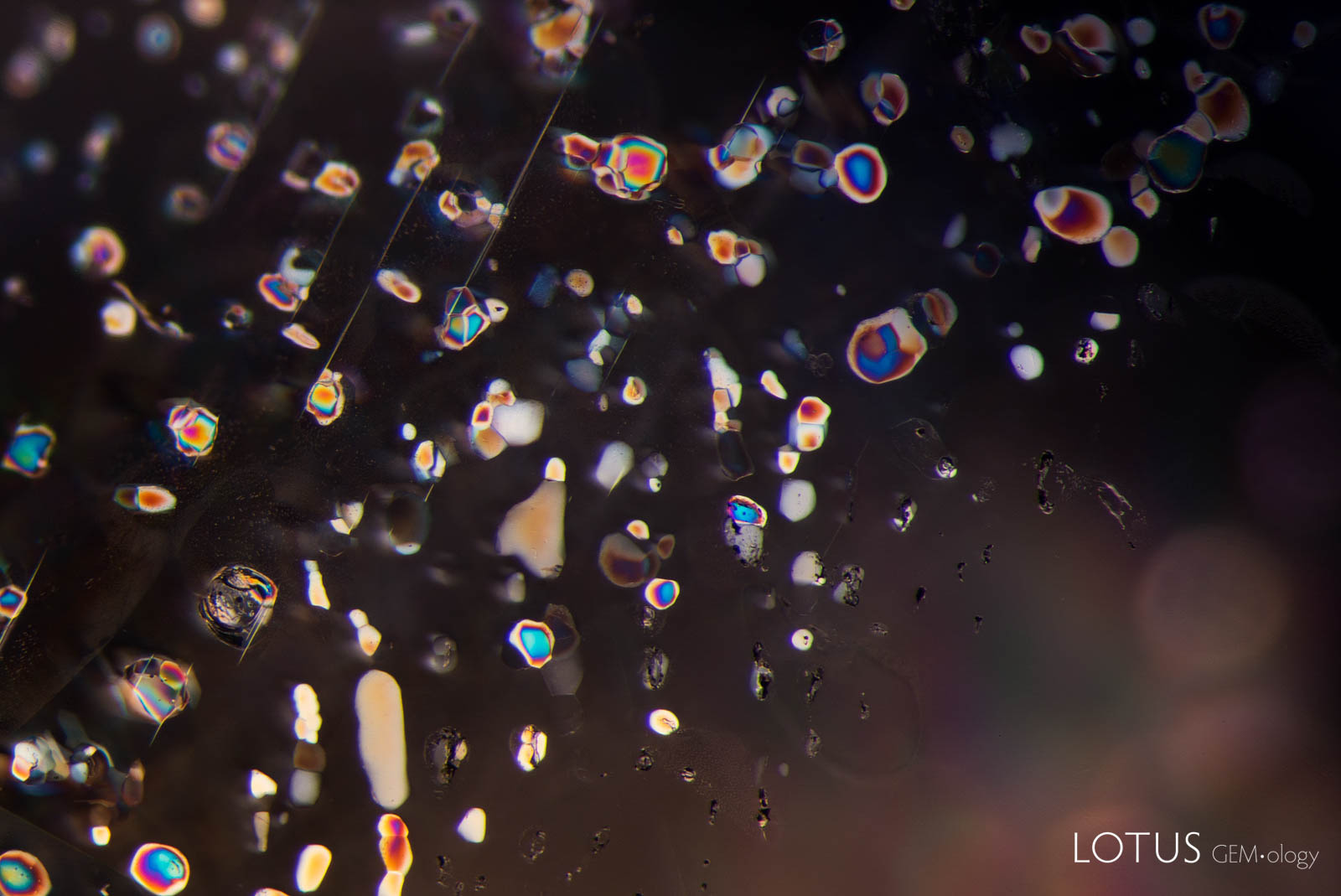

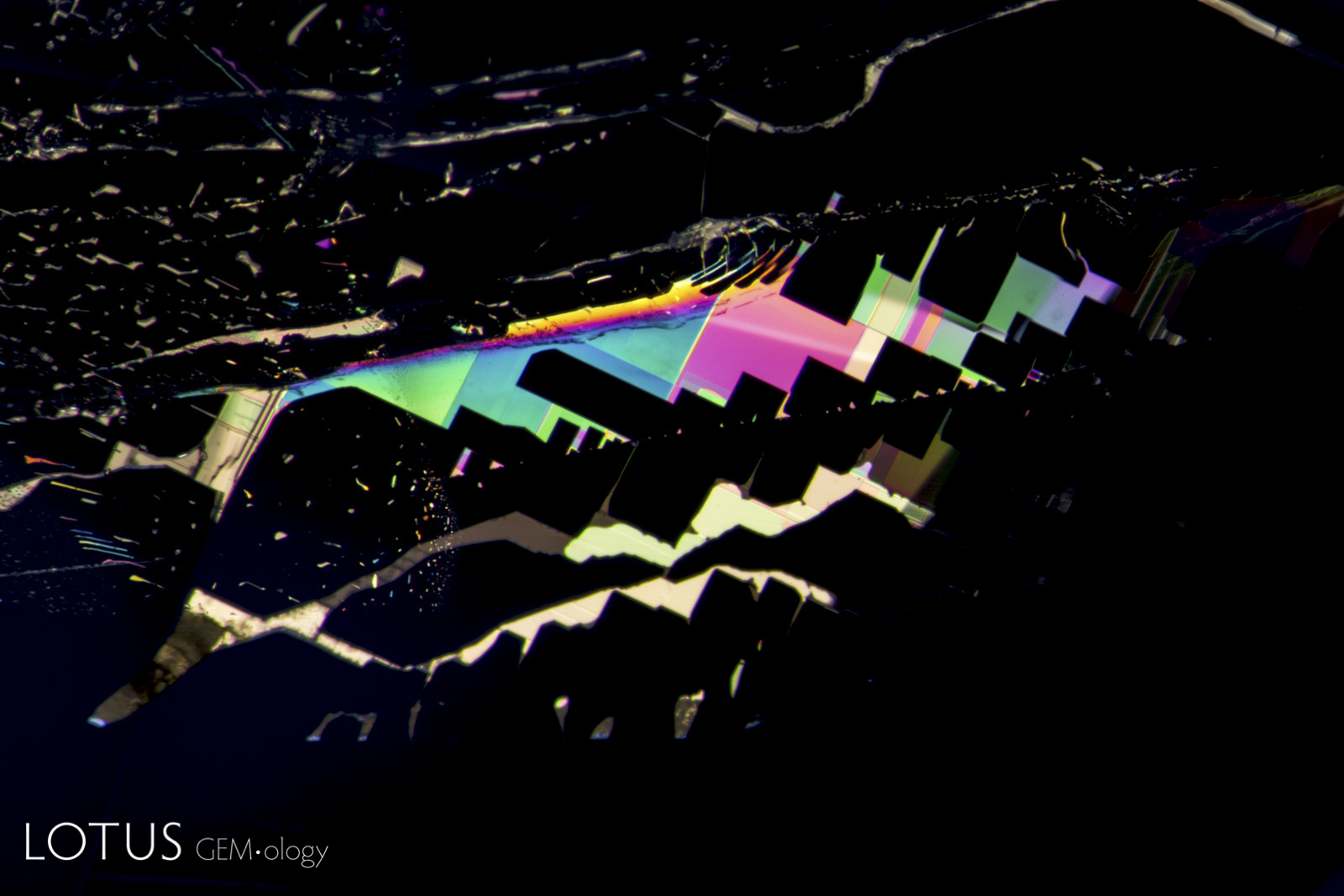

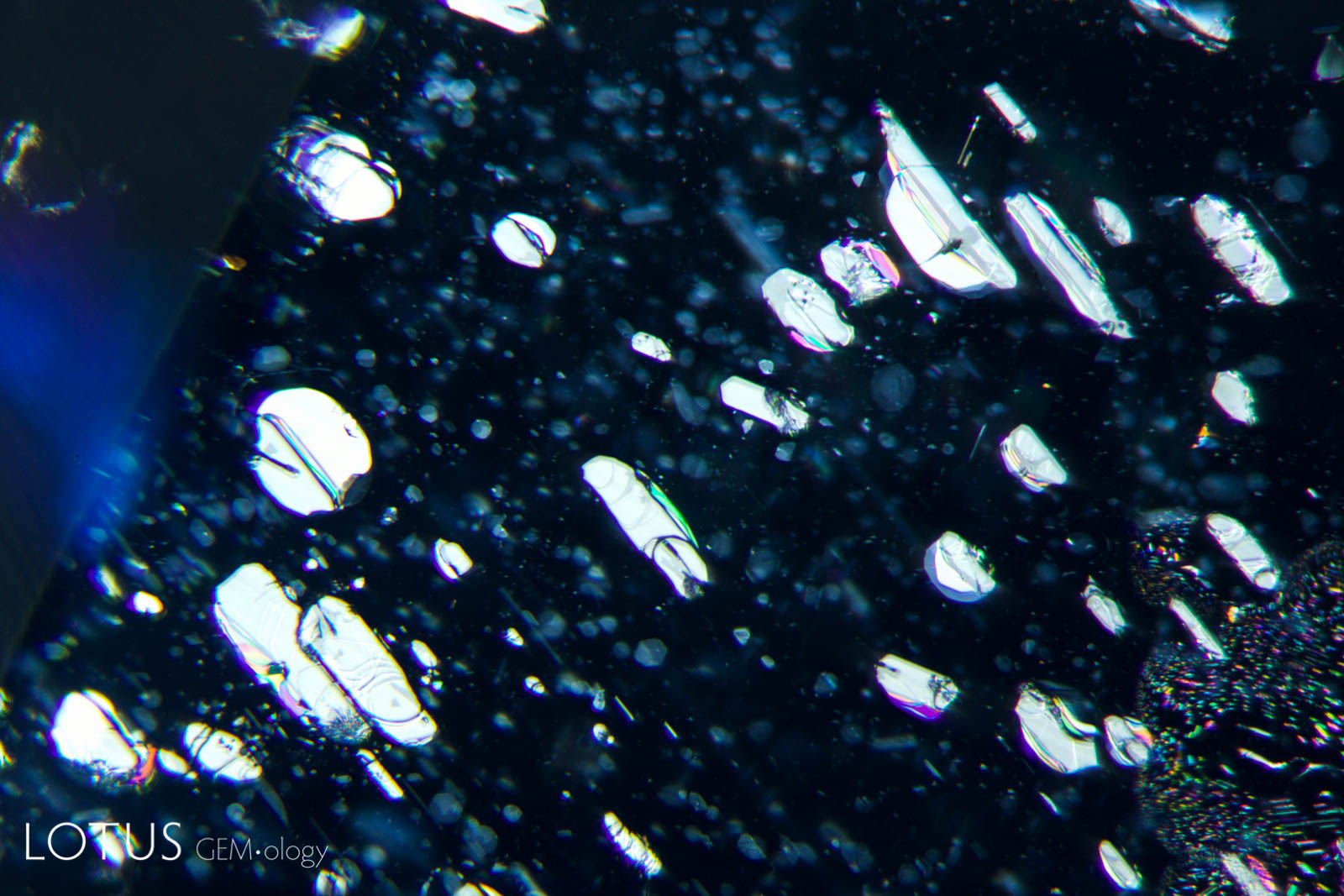

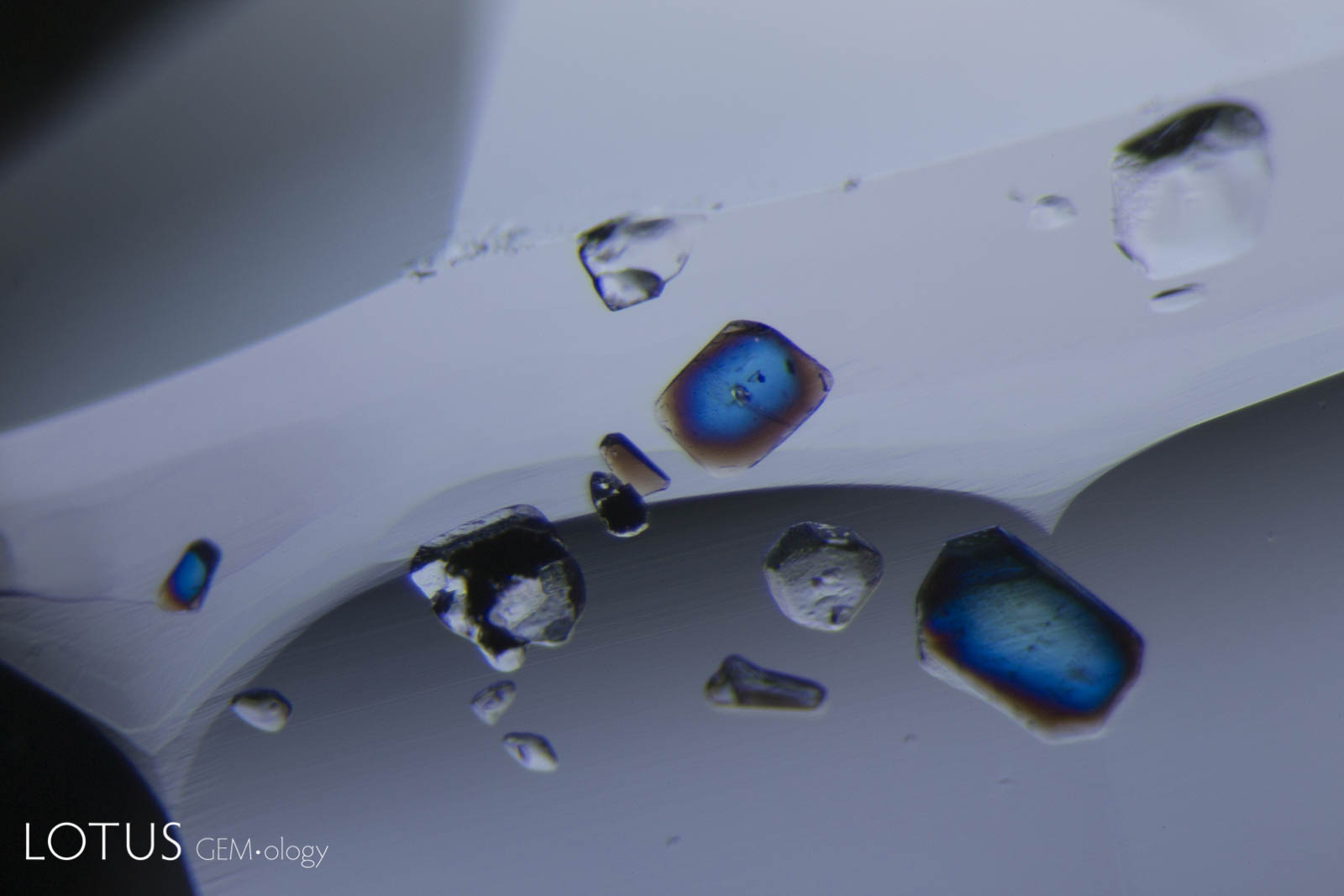

Left: Unusual birefringent crystals in a low-relief partially healed fissure in a sapphire treated with high-temperature heat plus modest pressure (HT+P). When tested with Lotus Gemology’s microraman, they proved to be corundum. It is thought that they crystallized during the treatment process. FOV 4 mm. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

From Top Left to Right: Secondary healed fissures in corundum are often filled with carbon dioxide, but usually in liquid form (solid carbon dioxide is what we know as “dry ice”). On occasion we see it in both liquid and gaseous form. This series of four images shows liquid carbon dioxide with a gas bubble (the yellow area). As the heat of the microscope warms the specimen, the gas bubble shrinks and eventually disappears. The critical temperature at which the phase changes is 31.2°C. The existence of carbon dioxide inclusions in sapphire was first noted by David Brewster in 1826. He also noted the explosive nature of such inclusions, which burst at temperatures generally between 250–400°C. Photos: Richard W. Hughes |

|

|

|

|

Left: Rosette inclusion surrounding a mica crystal in an unheated Mozambique ruby, seen in transmitted. |

|

|

|

|

Left: Overhead lighting was used to photograph this scene in a violet sapphire from Sri Lanka, which shows two large mica plates. The undamaged state of the mica reveals that this sapphire has not been subjected to heat treatment. |

|

|

|

|

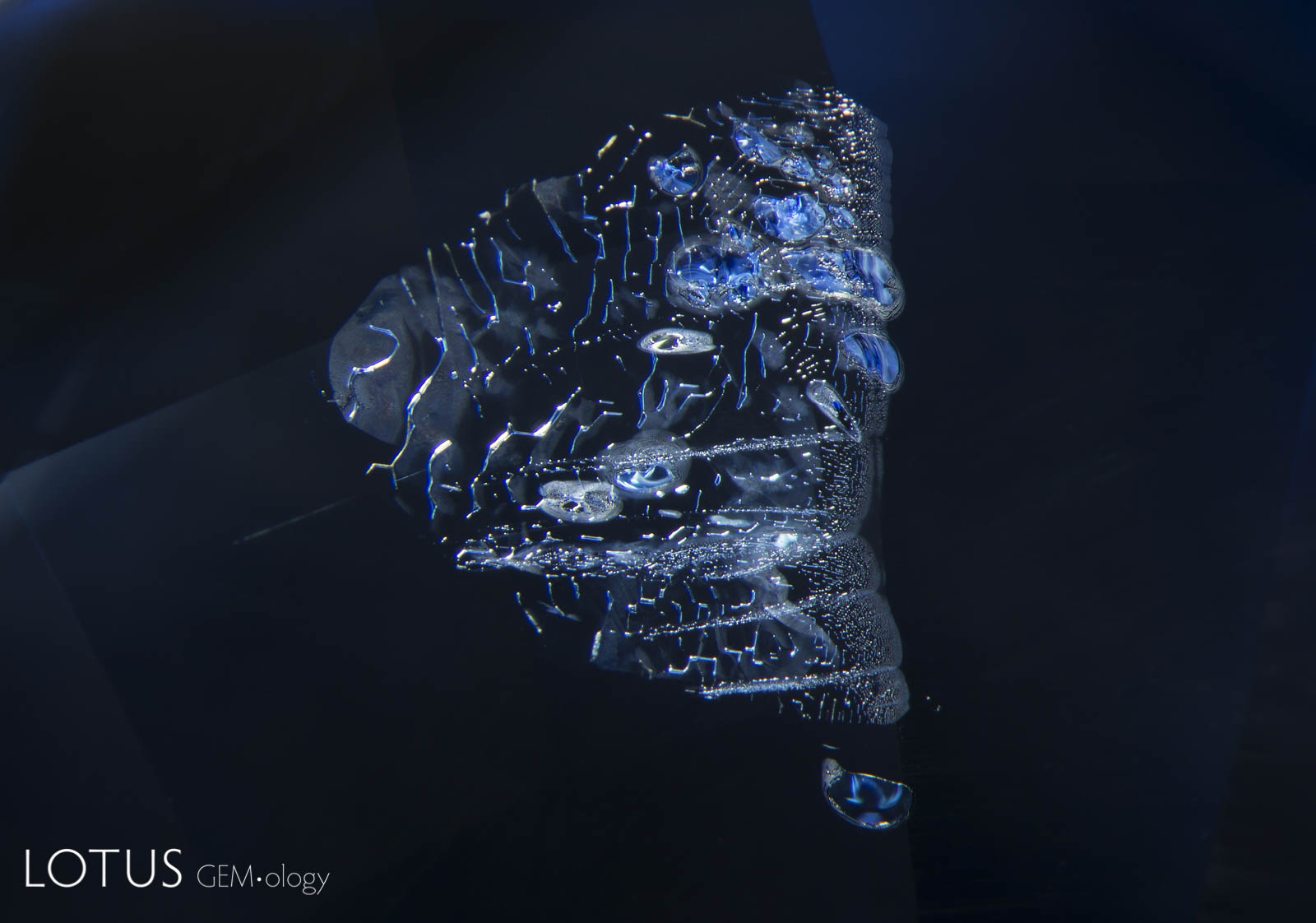

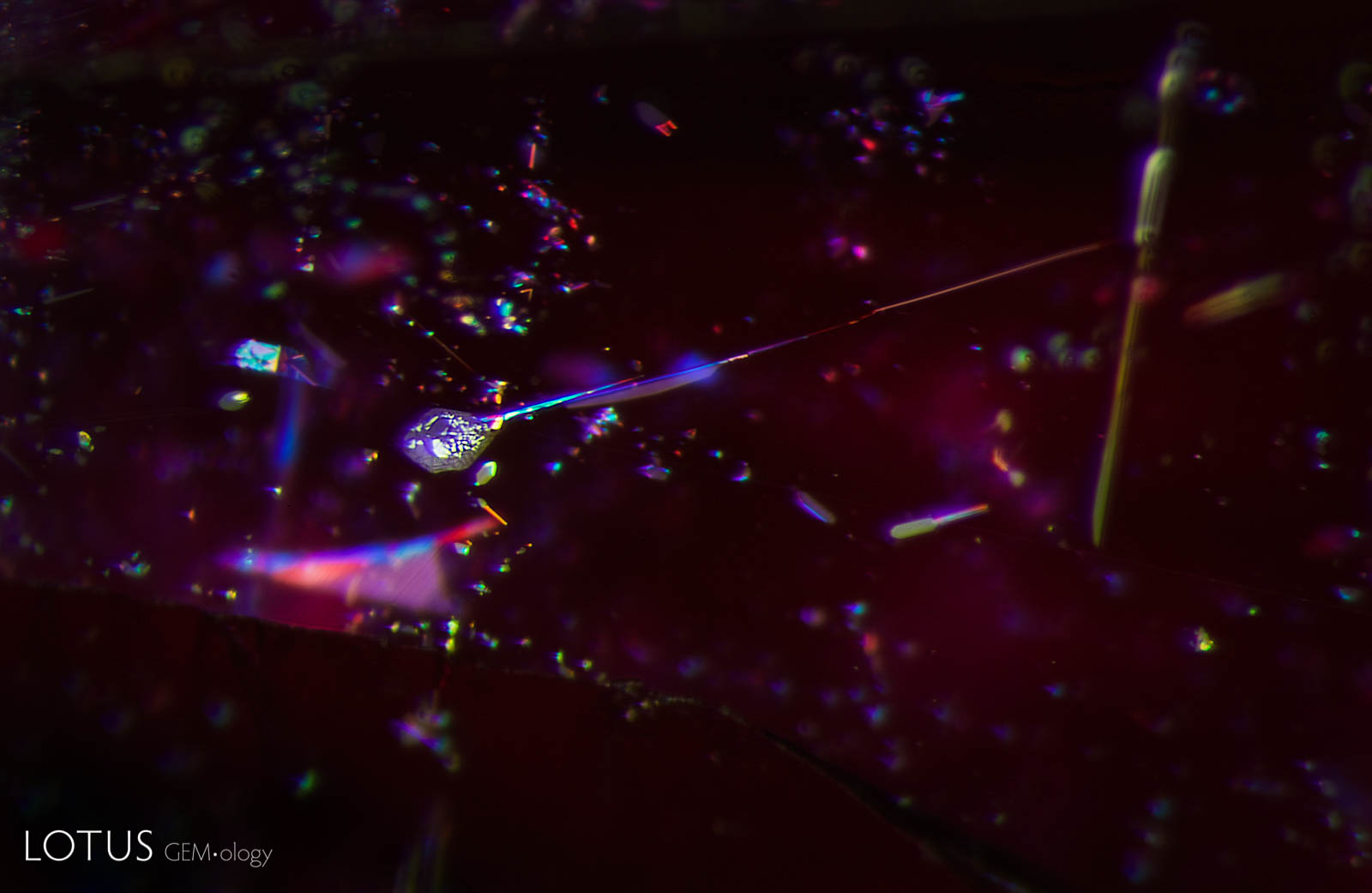

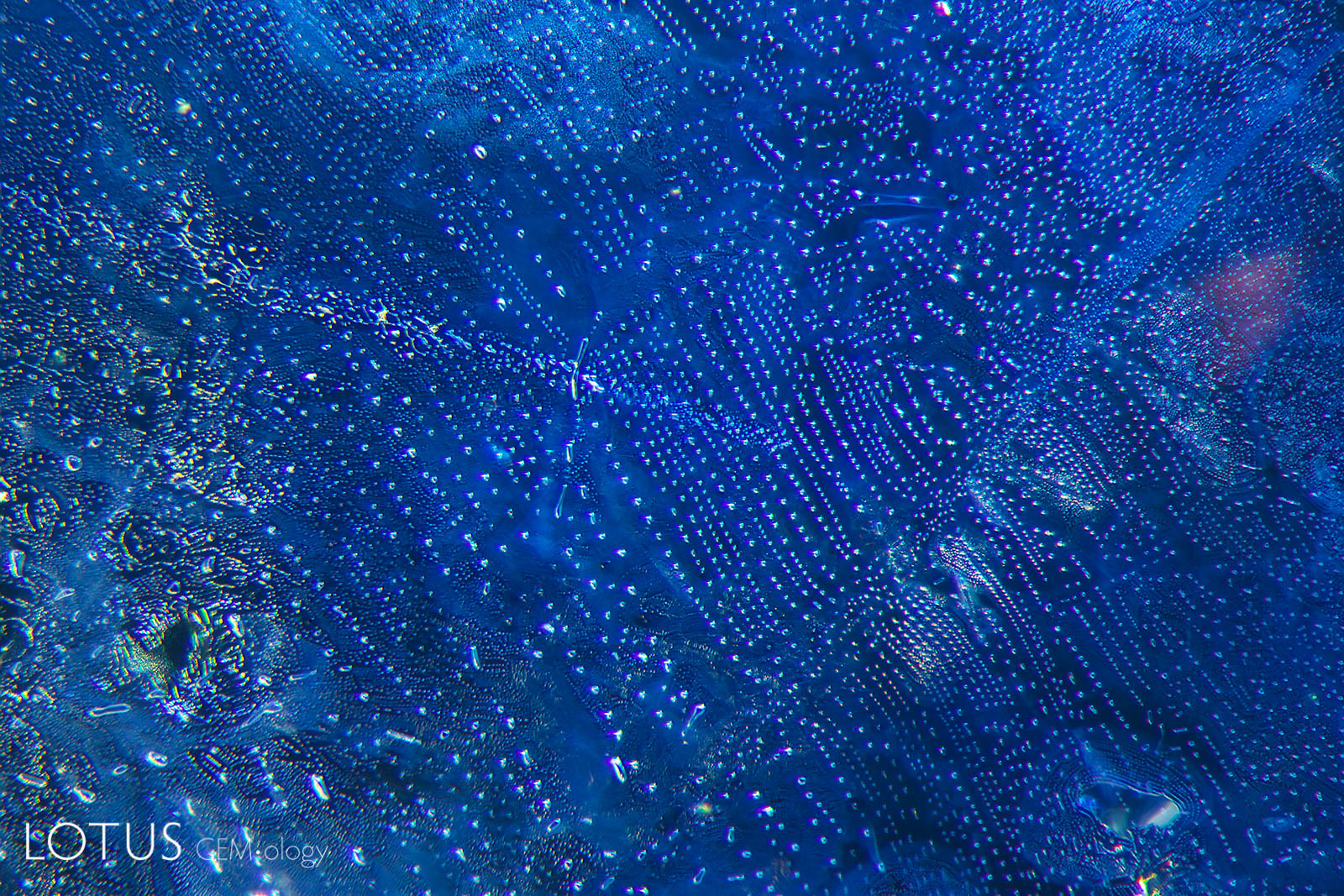

Left: In this flattened negative crystal in a Sri Lankan padparadscha sapphire, multiple phases can be found, including both liquid and gaseous carbon dioxide and a diaspore needle. Because diaspore’s refractive index (nα = 1.682–1.706; nβ = 1.705–1.725; nγ = 1.730–1.752) is so close to corundum (nω = 1.762; nε = 1.770) the diaspore needle almost disappears into the sapphire, appearing like a narrow indentation into the negative crystal. Liquid carbon dioxide becomes a gas at a fairly low temperature, with just the heat of the microscope causing the bubble to disappear. Intact negative crystals such as this are positive proof that the specimen has not been heat treated. |

|

|

|

|

Left: A fingerprint with many small negative crystal channels showing no signs of heat-induced damage in a sapphire from Madagascar. |

|

|

|

|

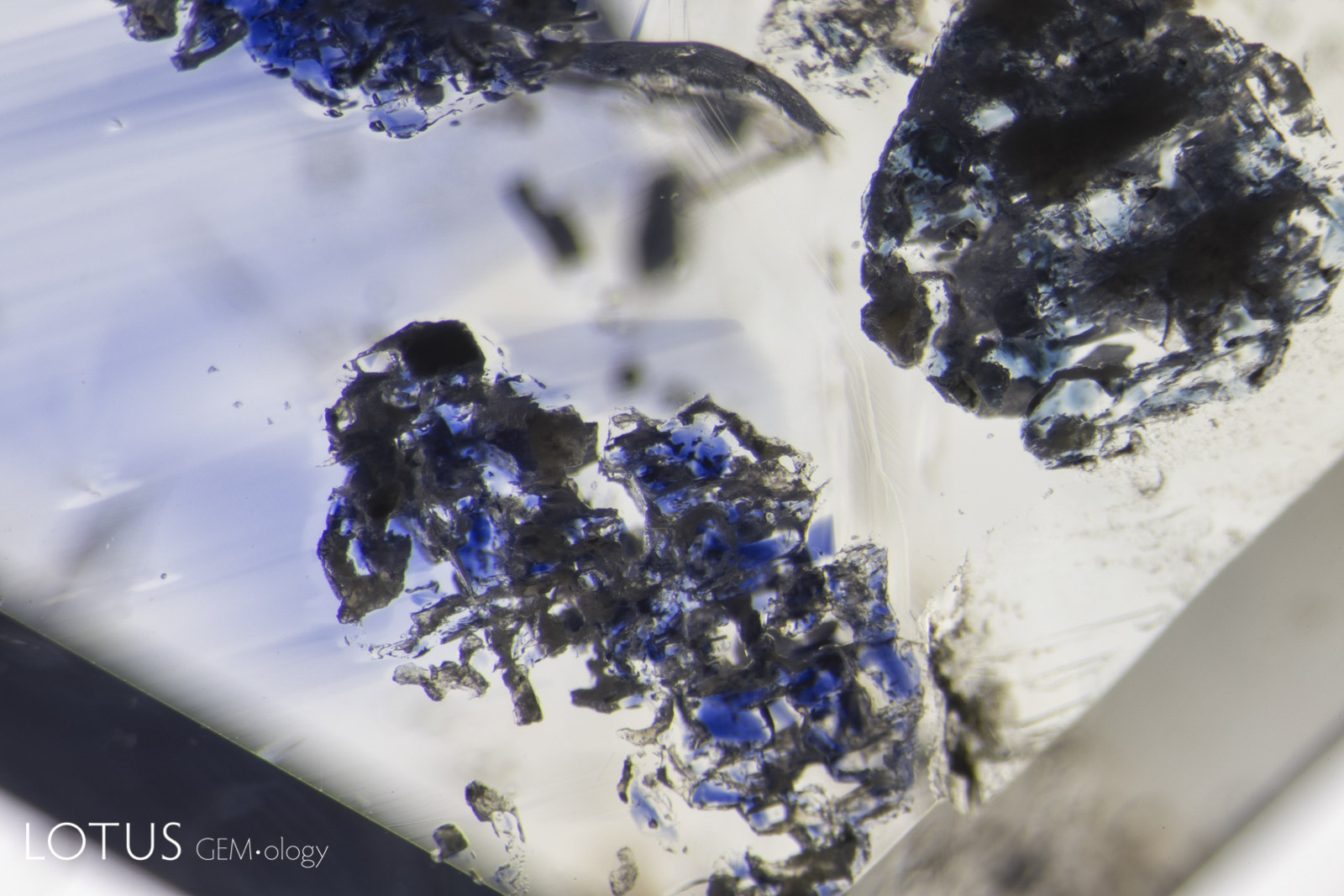

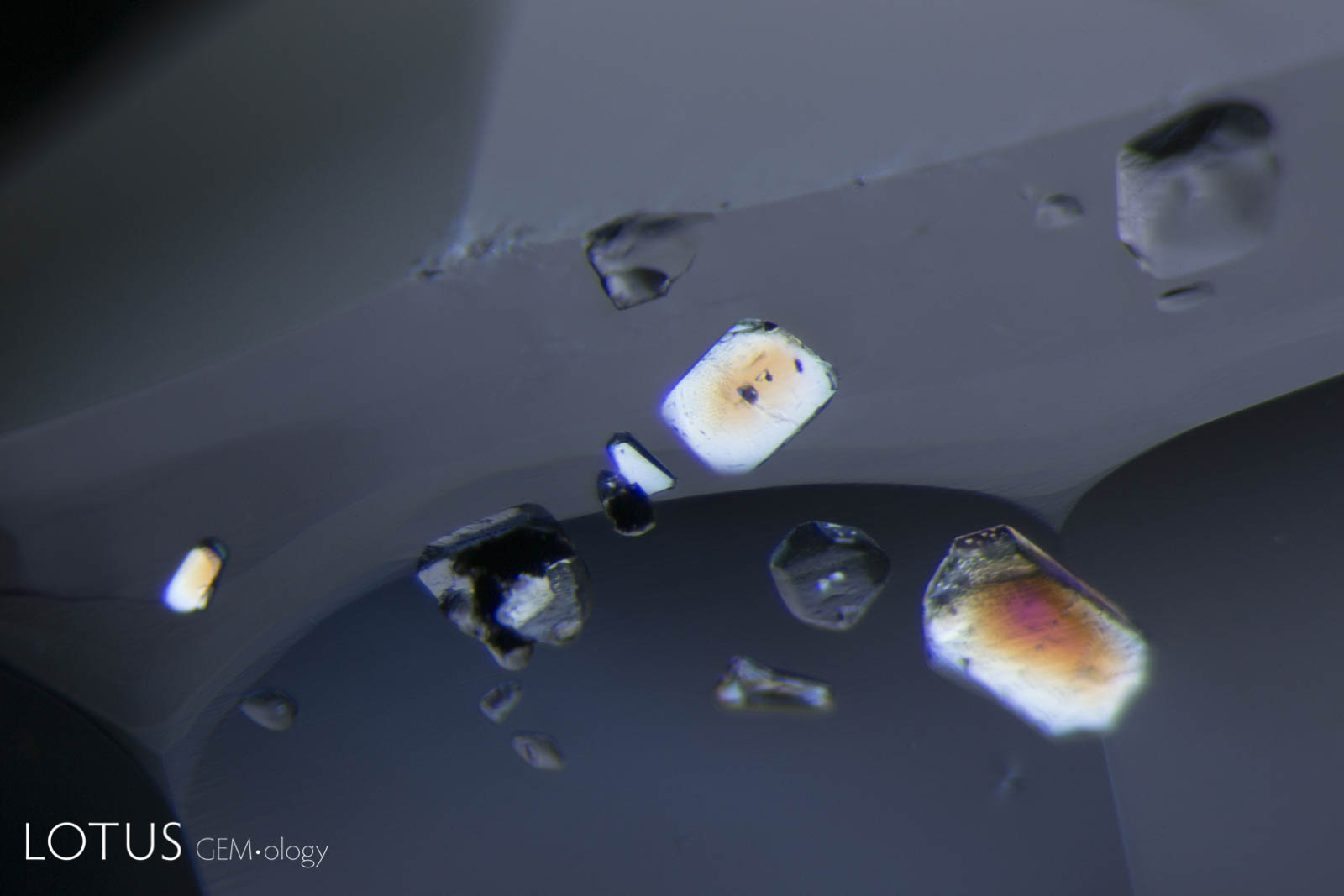

Left: Brown monazite crystals are sometimes found in sapphires from Madagascar’s Ilakaka region. In this gem one can see glassy tension halos around each, indicating that the gem was subjected to low temperature (less than 1400°C) heat treatment. |

|

|

|

|

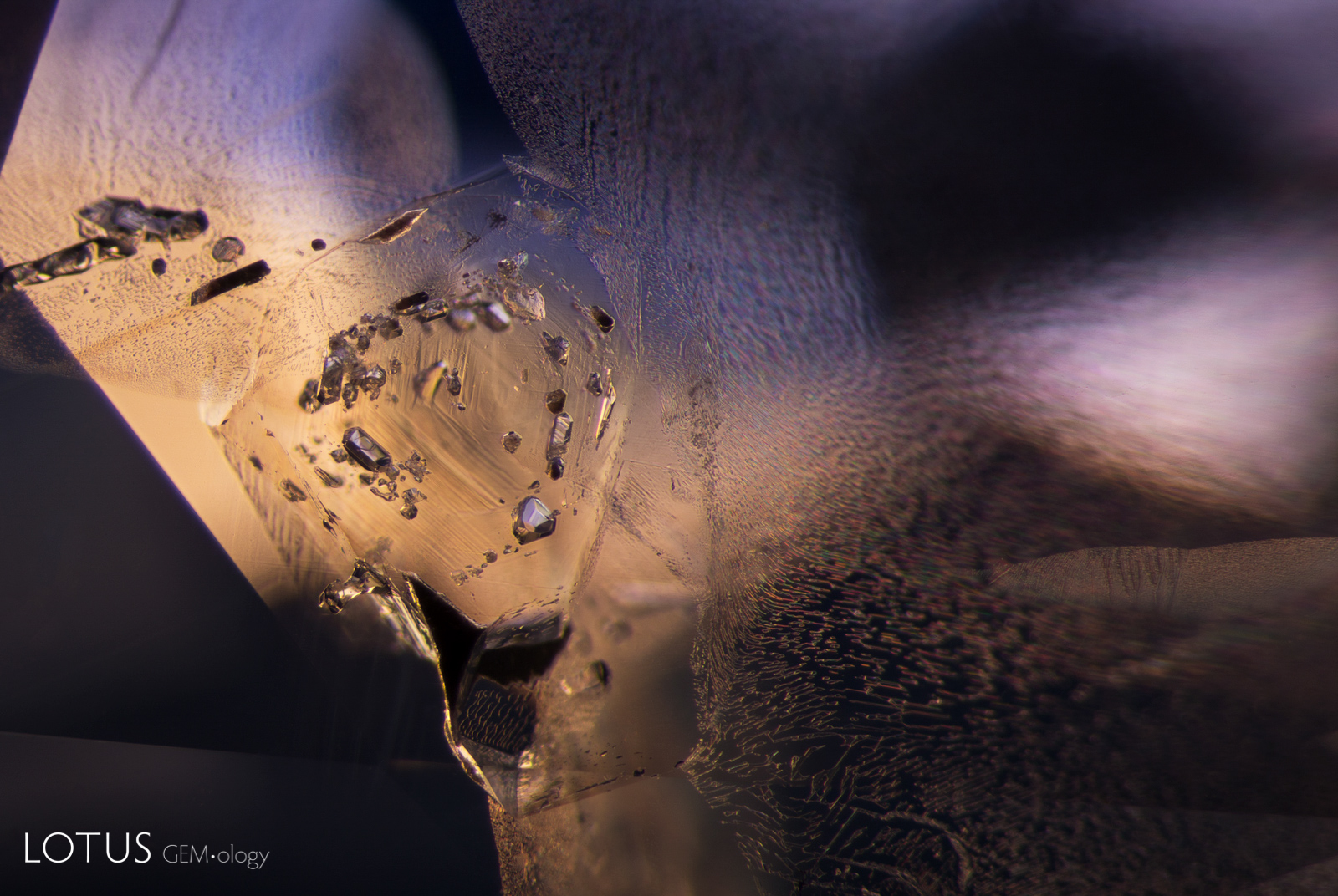

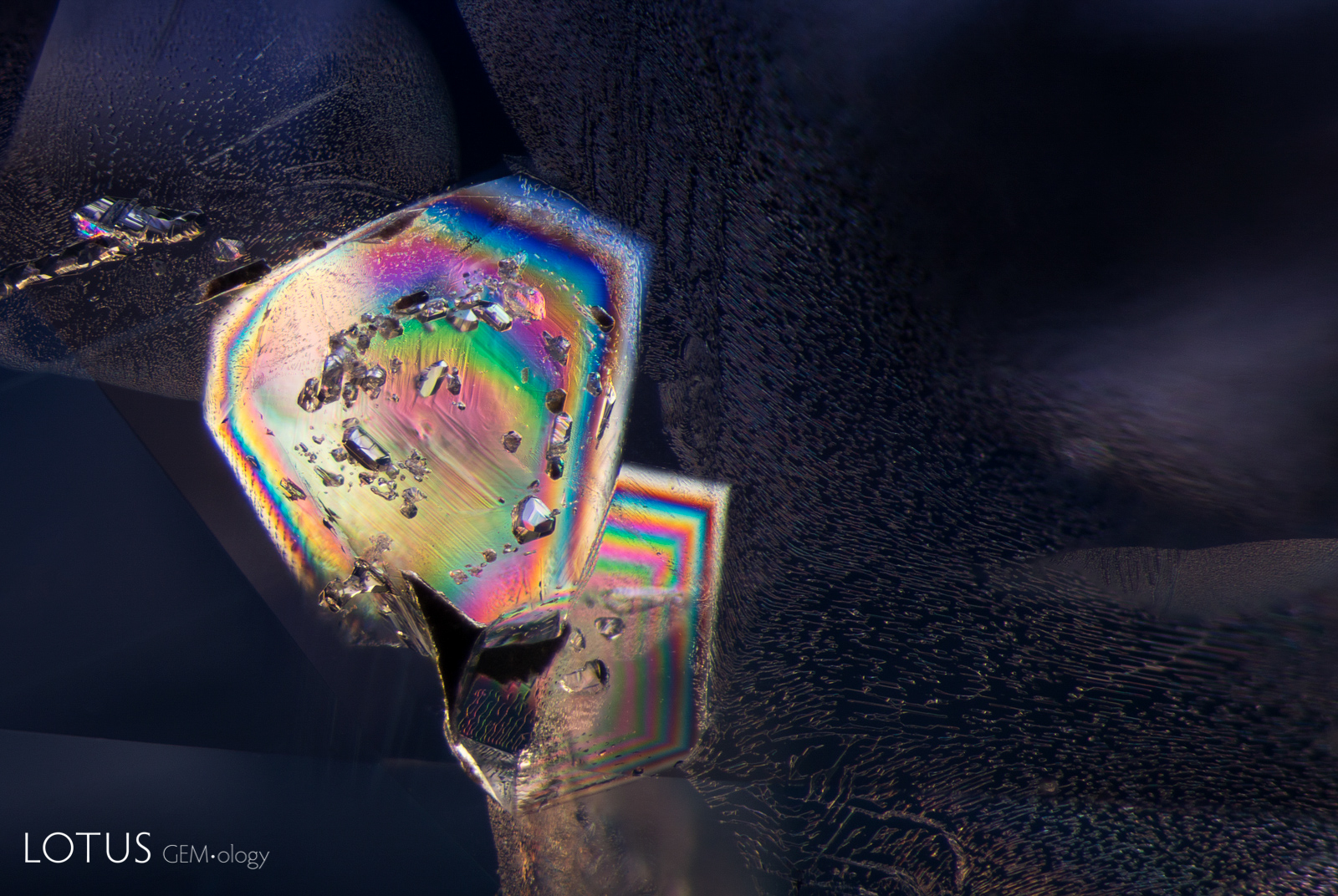

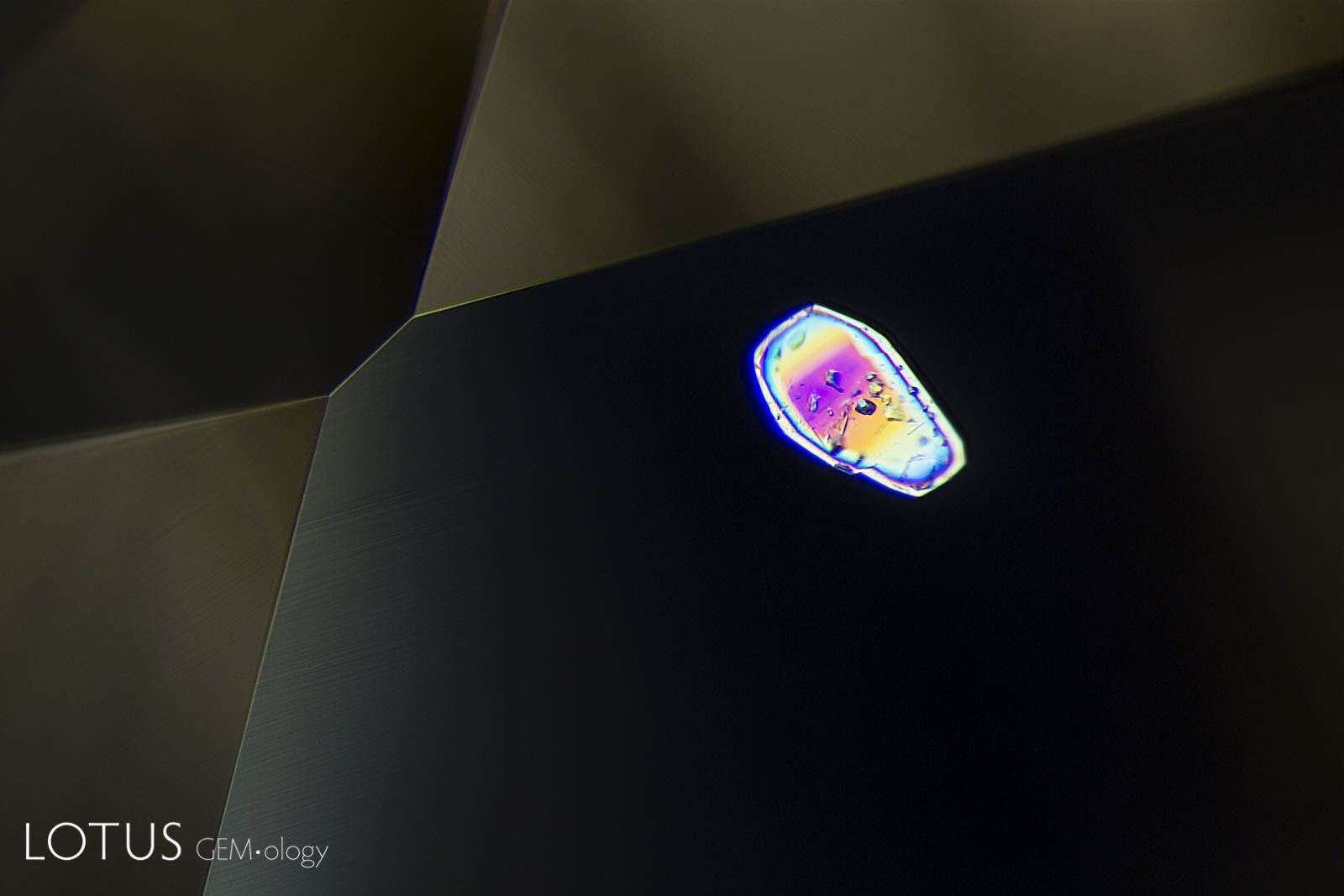

Left: A heat-altered crystal with an iridescent decrepitation halo, alongside a surface cavity filled with glass. |

|

|

|

|

Left: When a crystal is heated (either by a magma or artificially by human intervention), it expands. Tension is often relieved by a fissure in the weakest direction, which in corundum is in the basal plane. Such fissures are difficult to see in dark-field illumination. |

|

|

|

|

Left: Kashmir sapphires are unique in that the skin of many crystals feature deep blue spots of color, like spots on a leopard’s back. |

|

|

|

|

Left: Secondary "fingerprint" in a Mong Hsu (Myanmar) ruby before heating. Note the angular nature of the negative crystal channels. |

|

|

|

|

Left: A lovely rosette inclusion surrounds a mica crystal in this ruby from Mozambique’s Montepuez region. This “rosette” actually consists of negative crystals flattened in the plane of basal pinacoid (perpendicular to the c axis). Oblique fiber-optic lighting. |

|

|

|

|

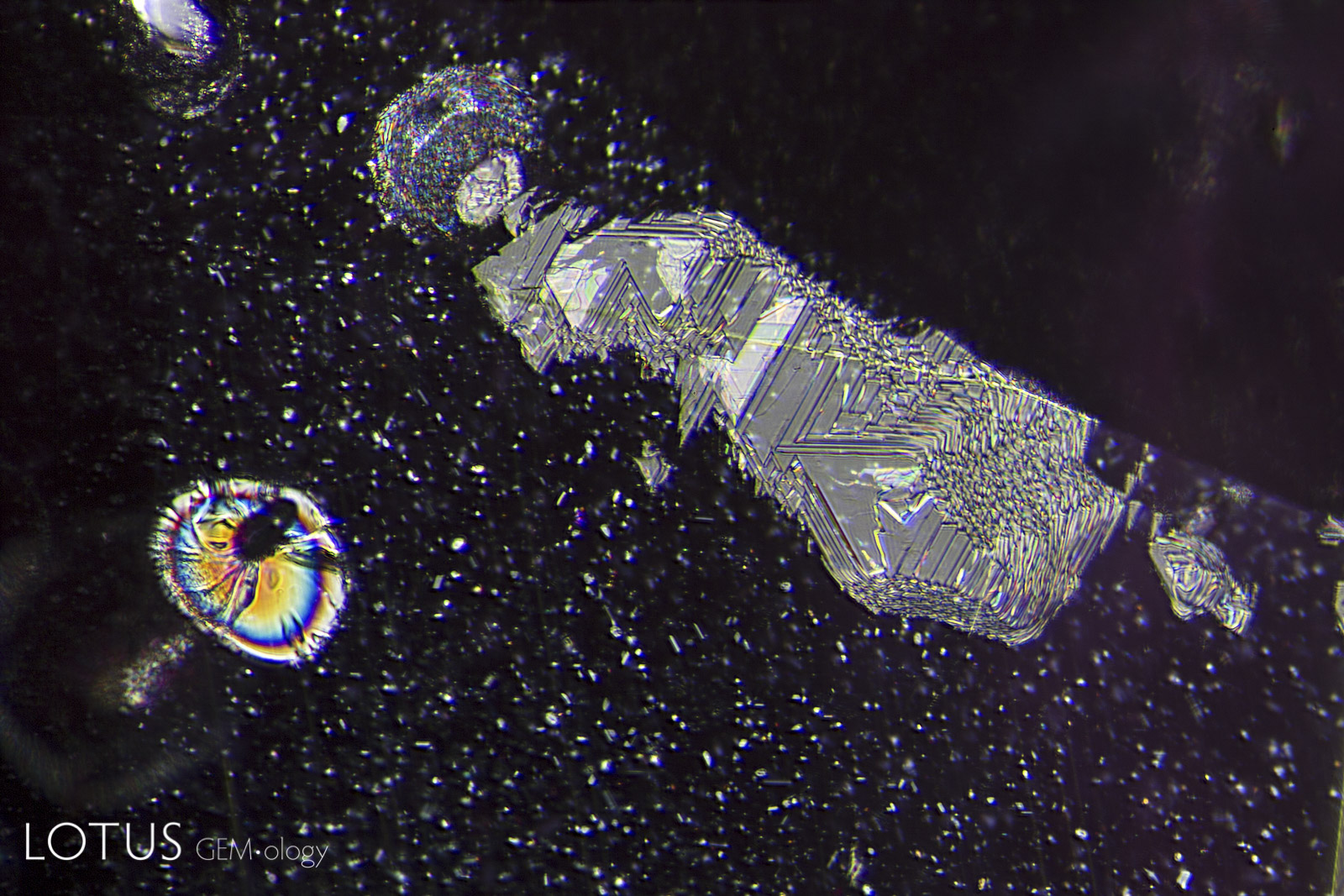

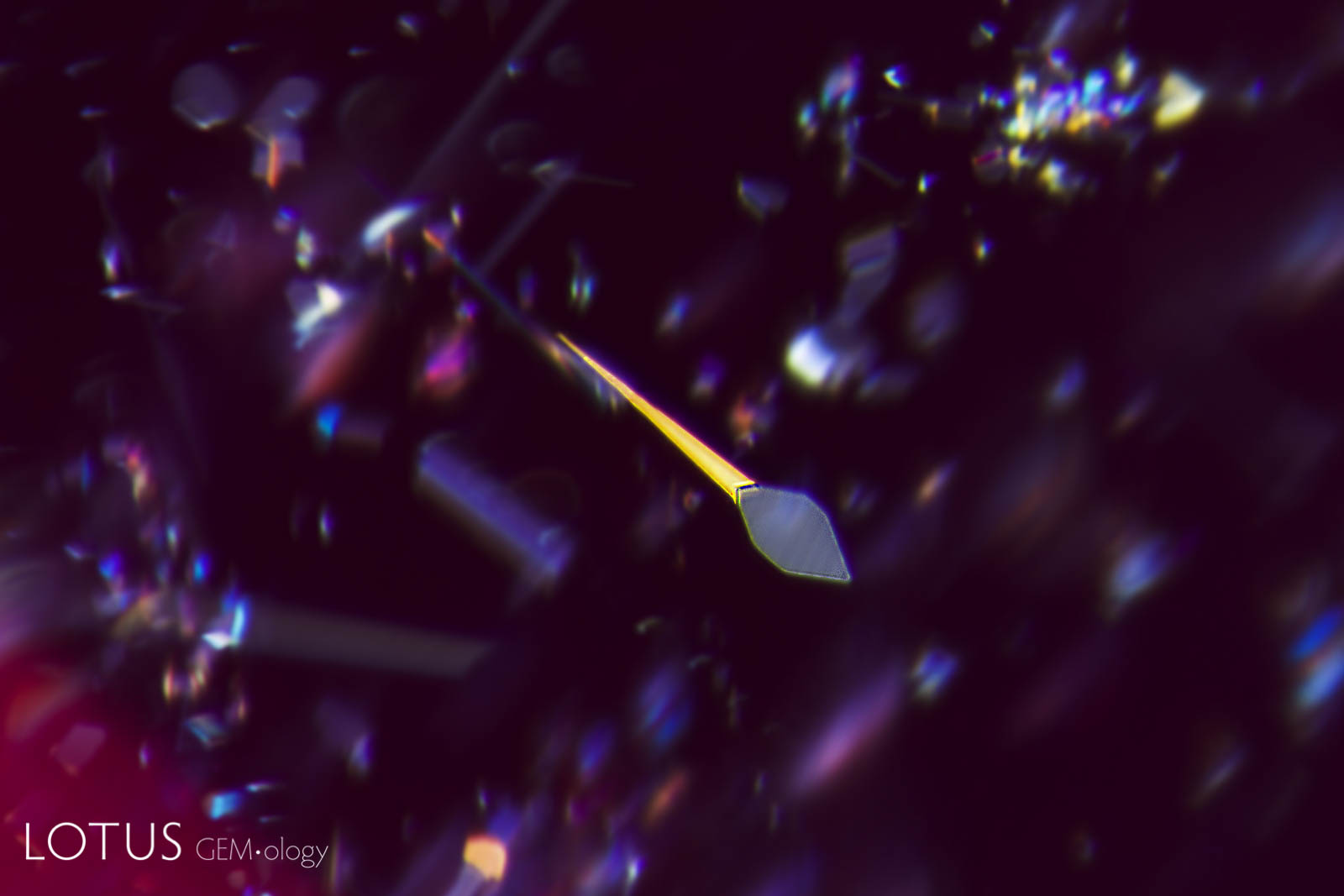

Left: Mozambique silk before heating shows a high luster rutile needle and an attached lower luster daughter crystal. |

|

|

|

|

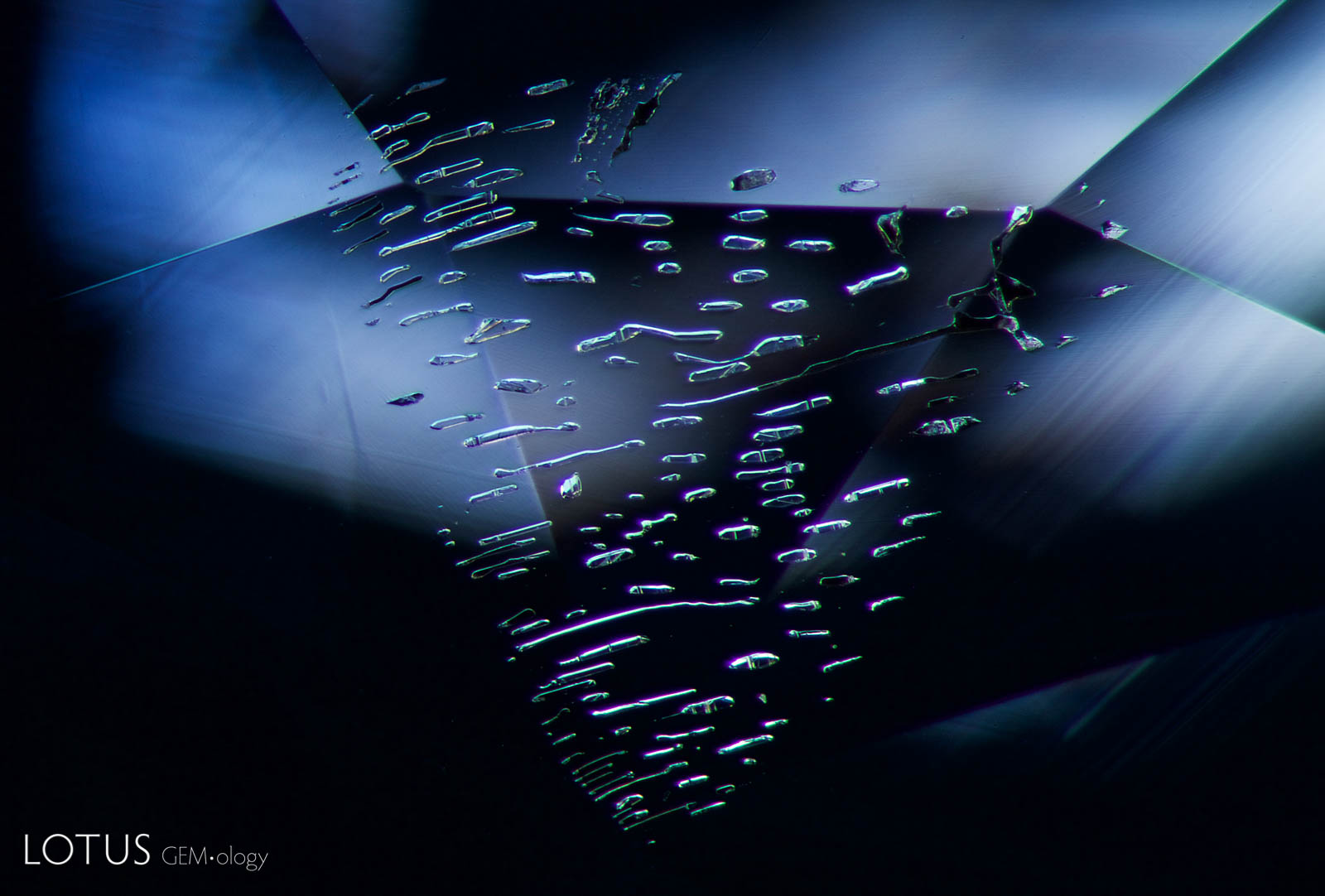

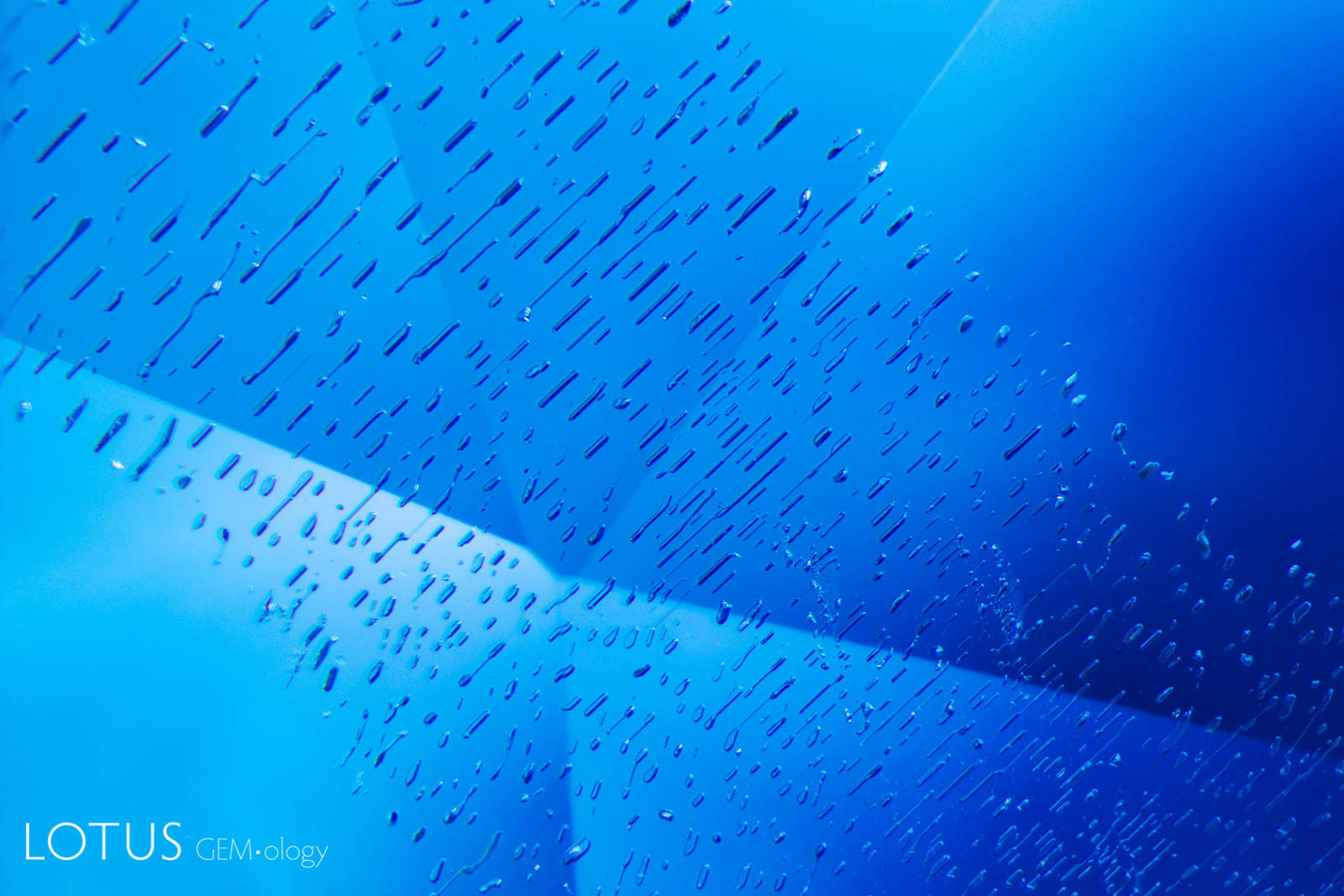

Left: Undissolved rutile silk in sapphire. This forms along three directions, intersecting at 60/120° in the plane of the basal pinacoid (perpendicular to the c axis). |

|

|

|

|

Left: Negative crystals in an untreated Mogok, Myanmar (Burma) sapphire in transmitted light. |

|

|

|

|

Left: Transparent crystals, seen at left in transmitted light, can be hard to distinguish from negative crystals. |

|

|

|

|

Left: This ruby from Madagascar contains a large cavity with a mobile CO2 bubble. |

|

|

|

|

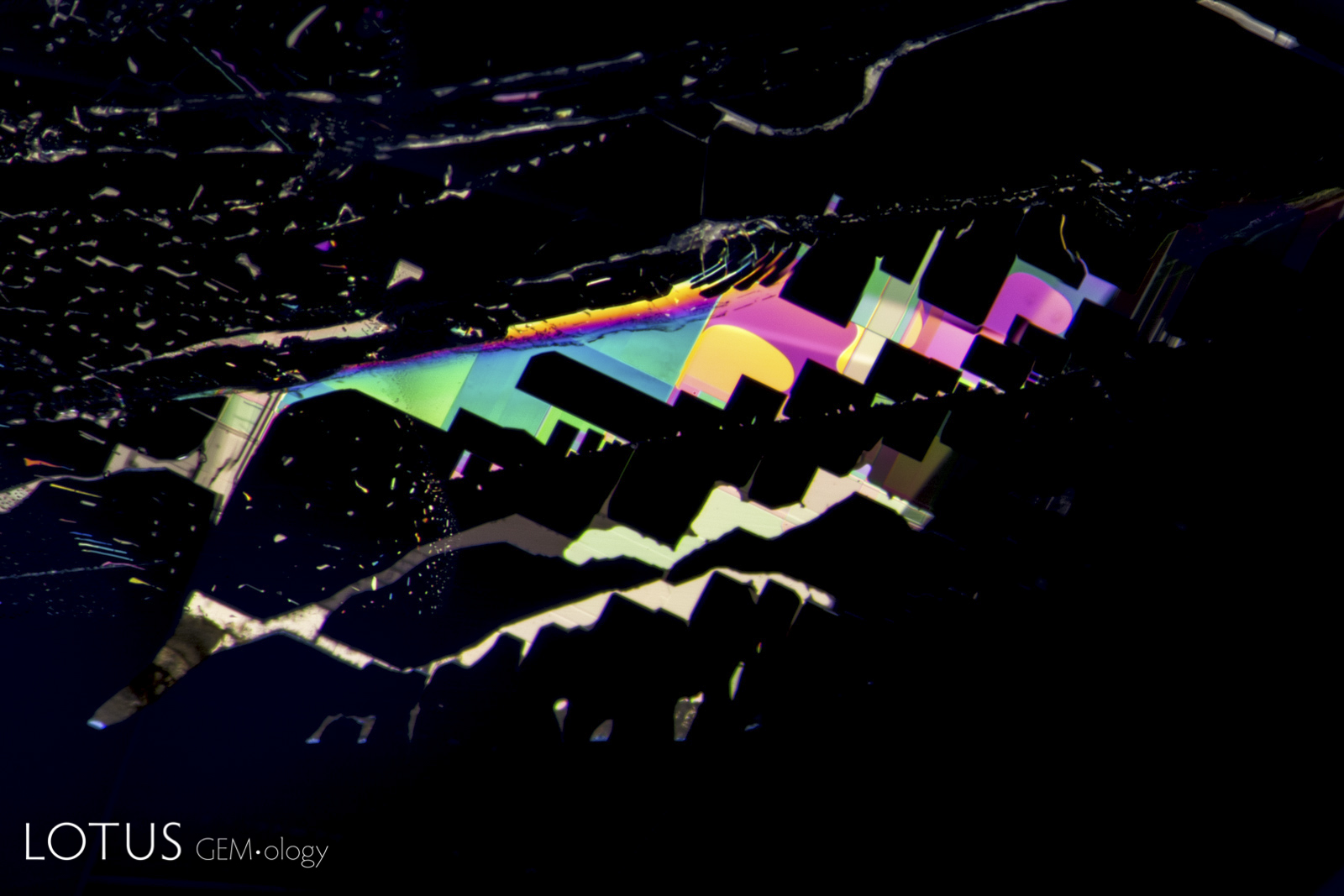

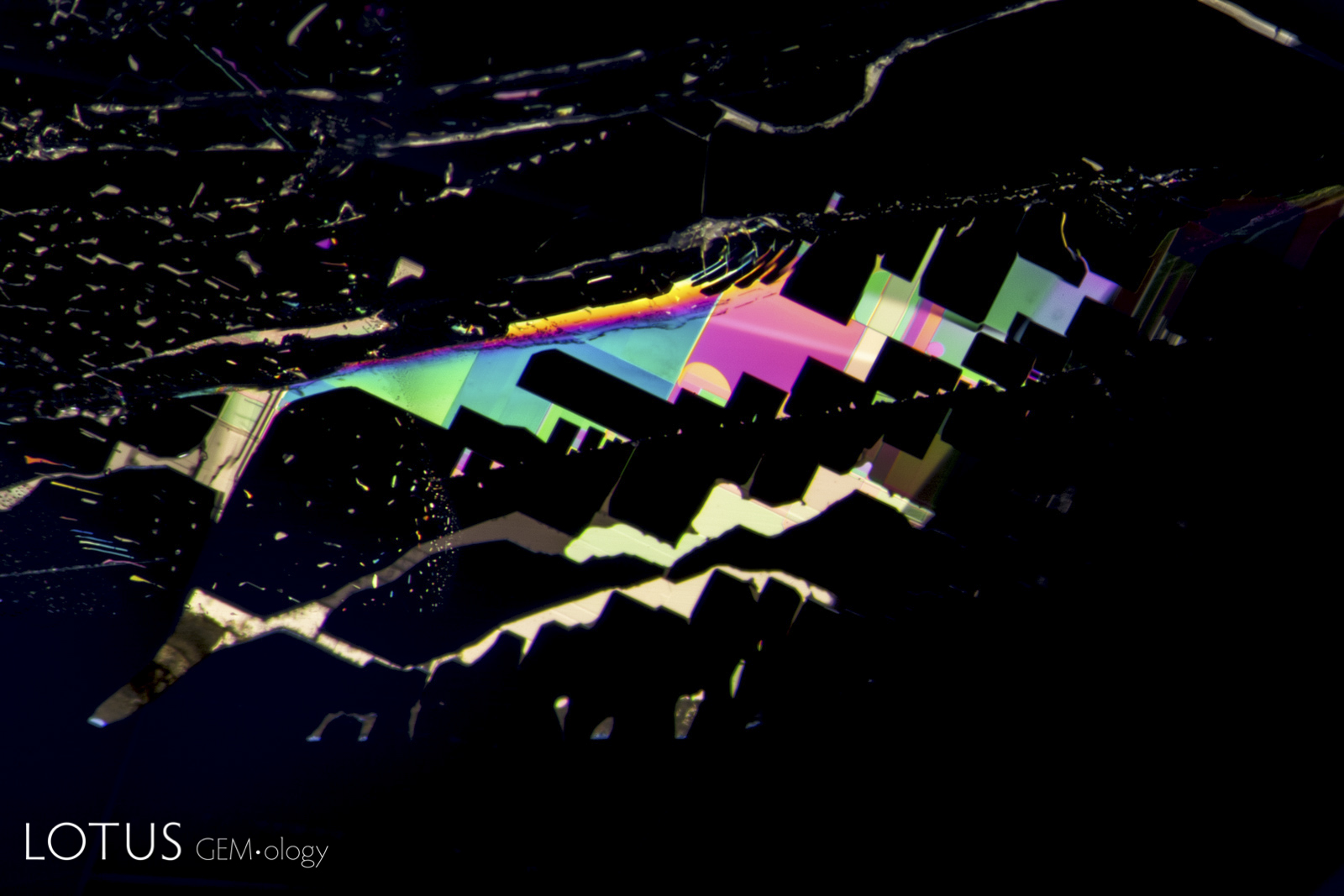

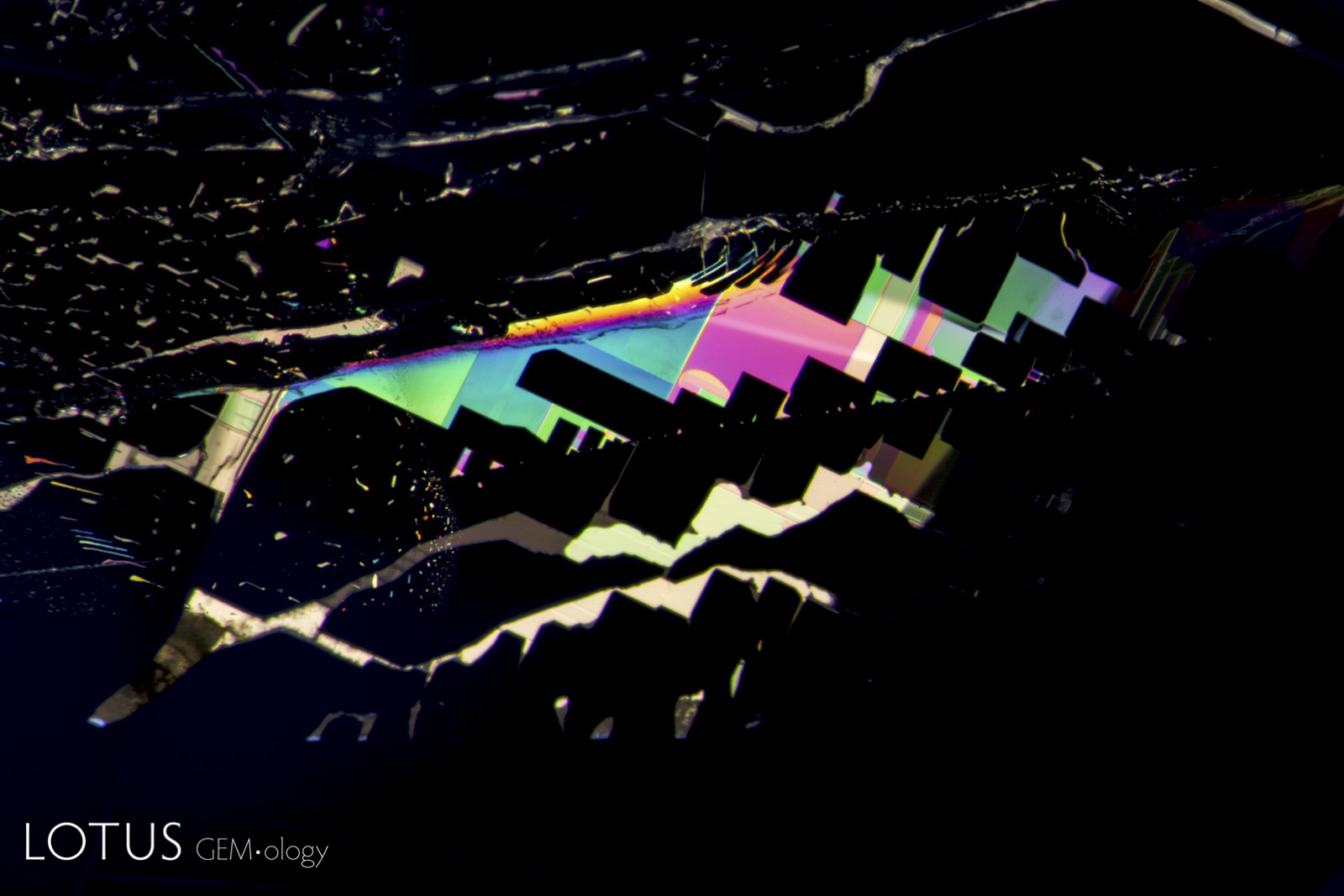

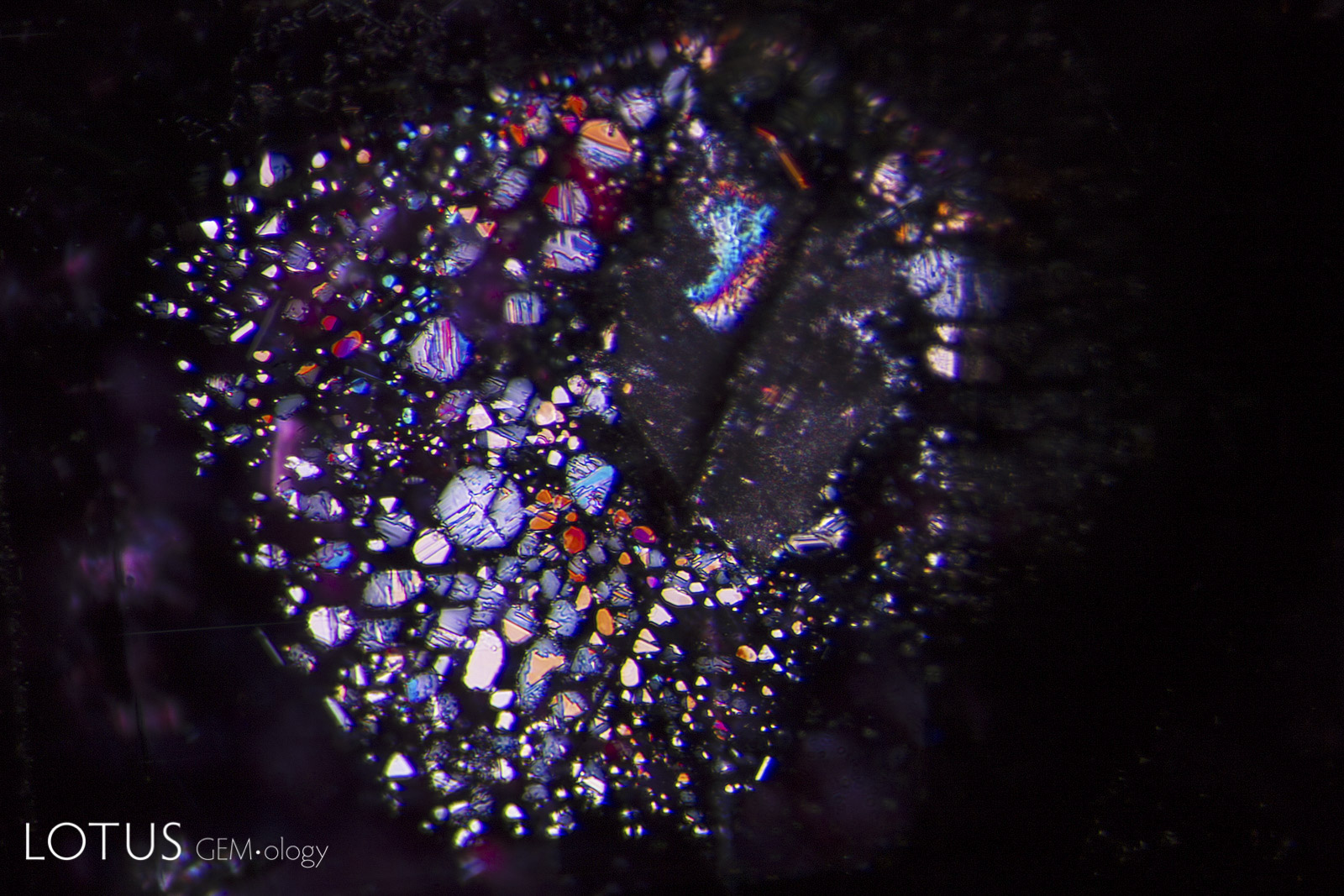

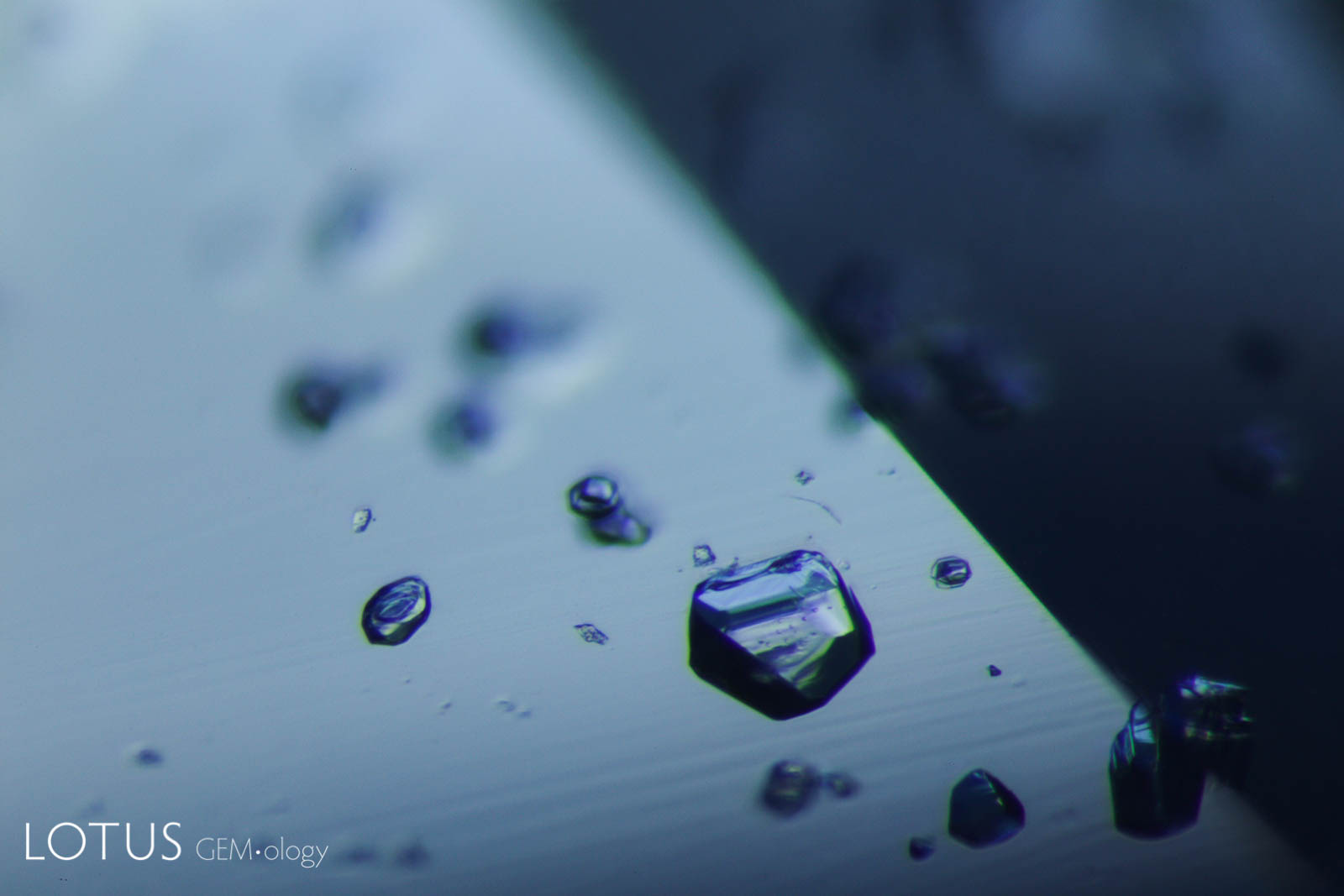

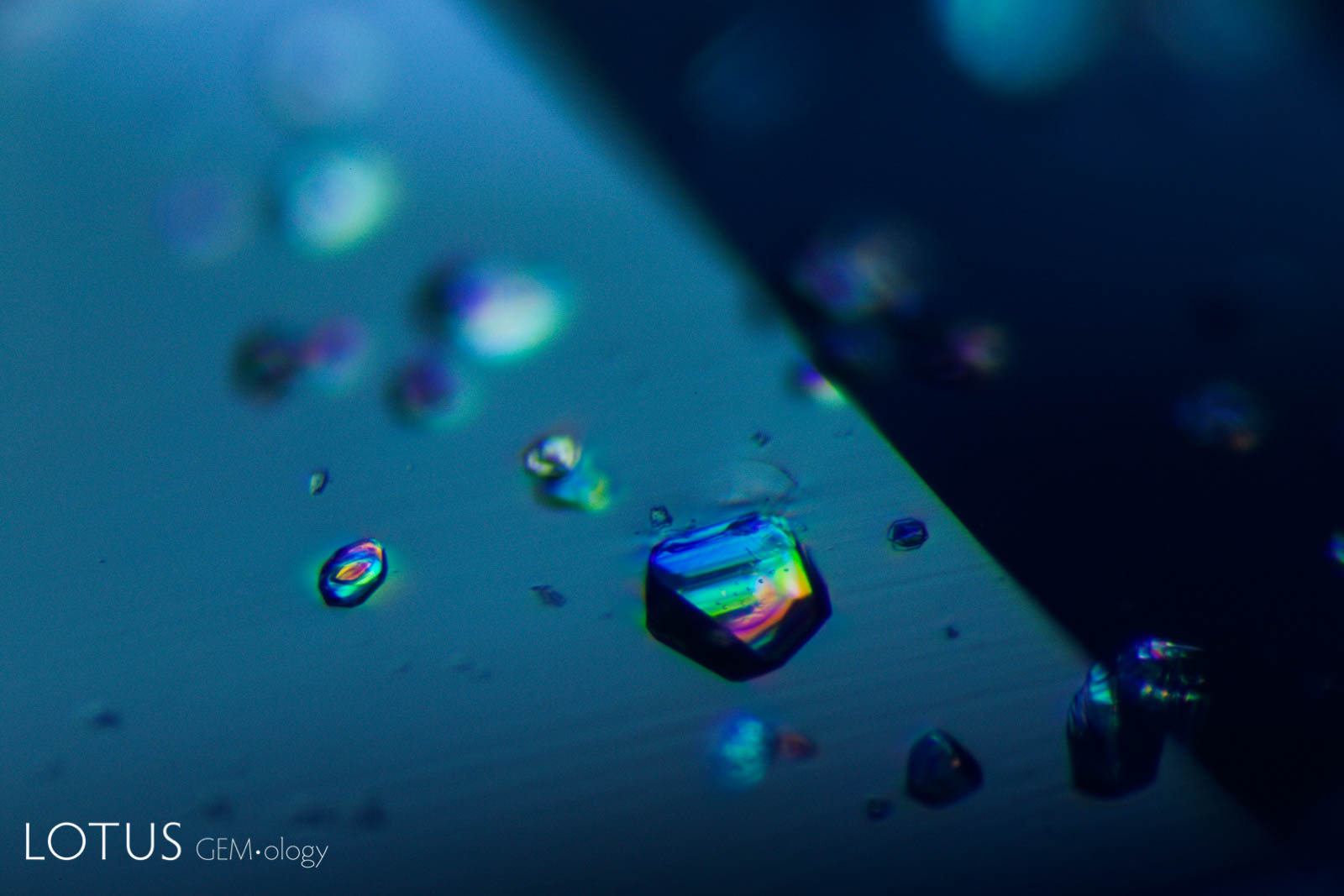

Left: Birefringent crystals light up in different colors in this sapphire from Sri Lanka when viewed between crossed polars. |

|

|

|

|

Left: Partially healed "fingerprint" in a Sri Lankan sapphire, before heating. Note the pristine nature of the tiny negative crystals. |

|

|

|

|

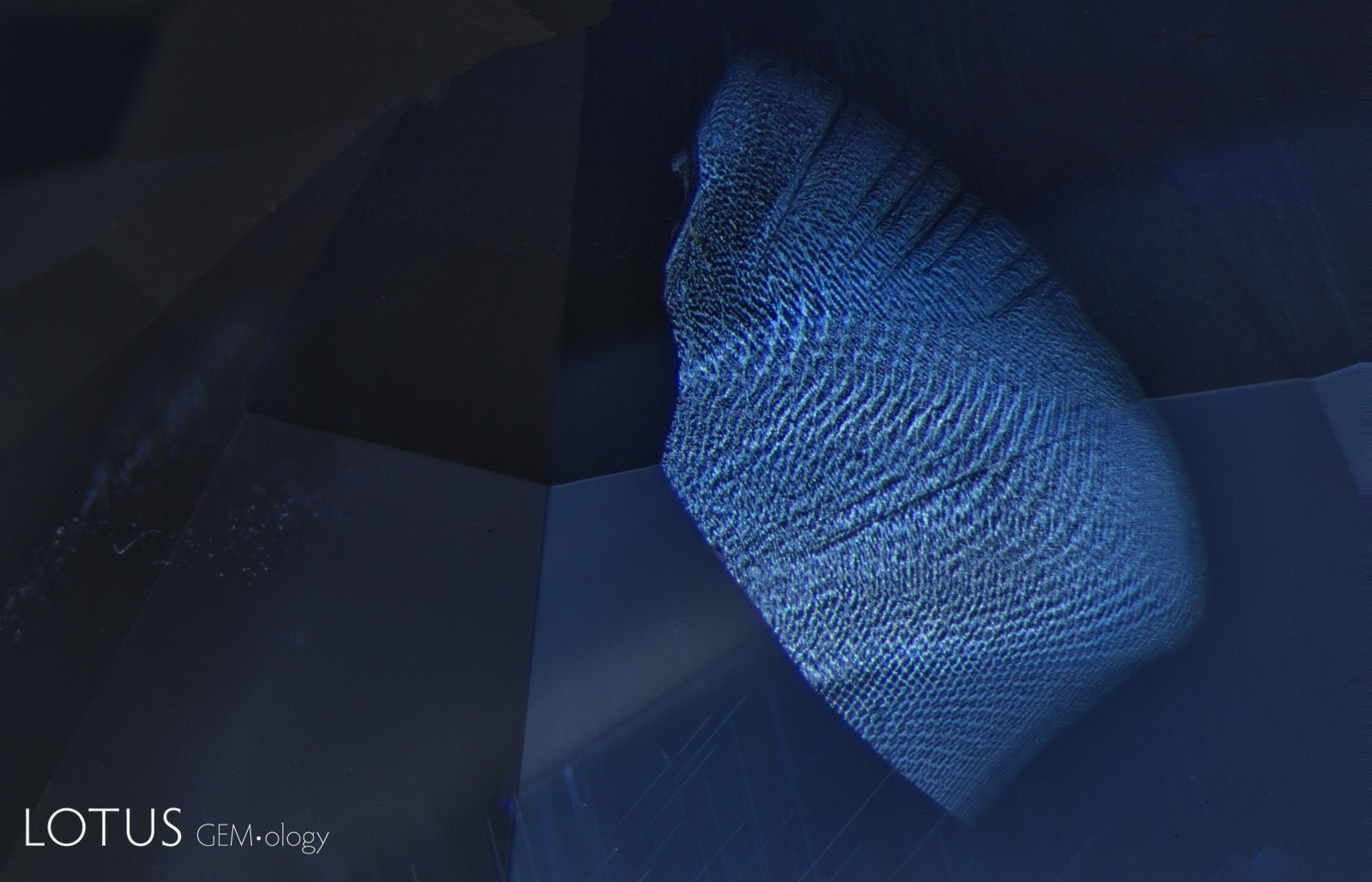

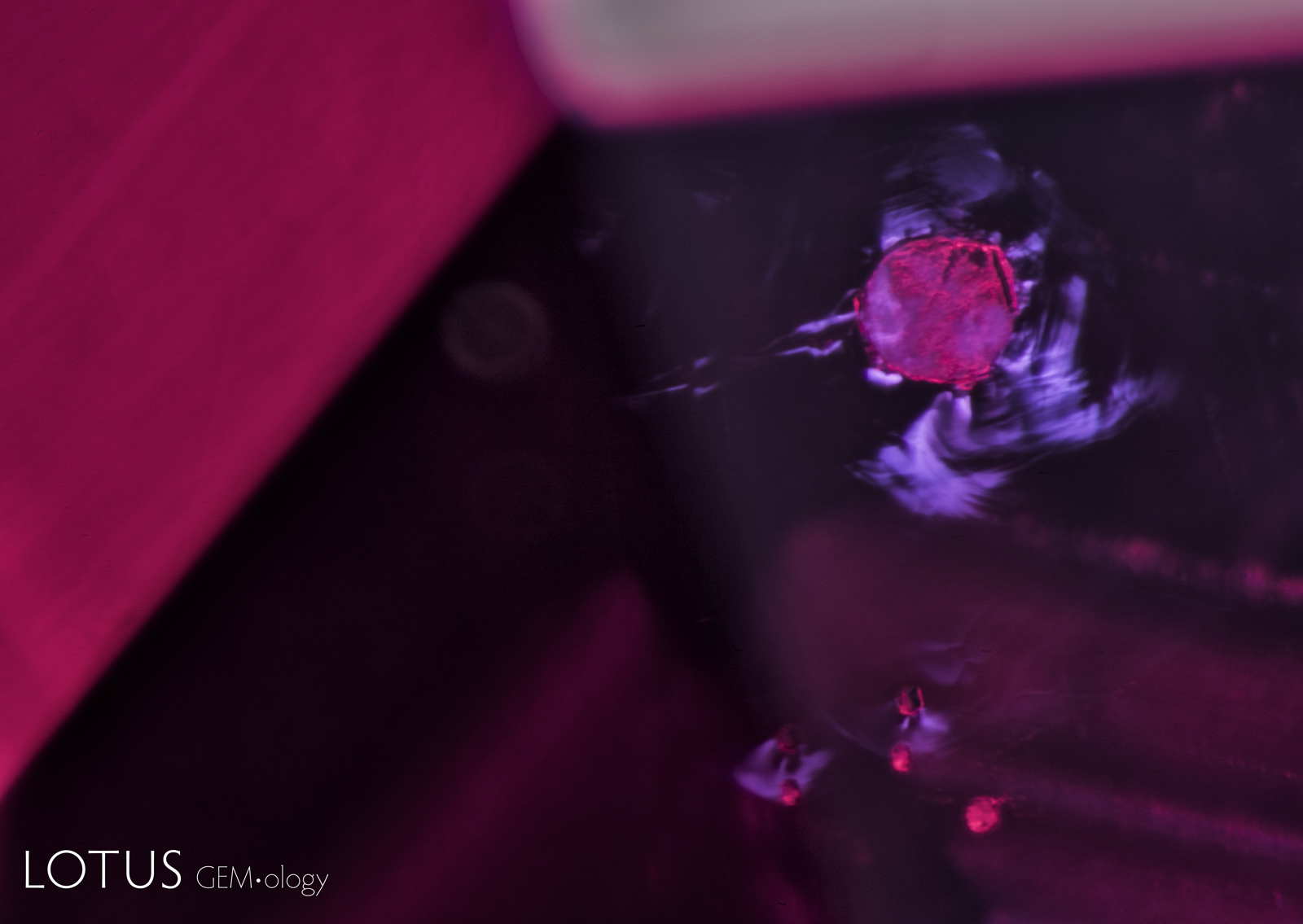

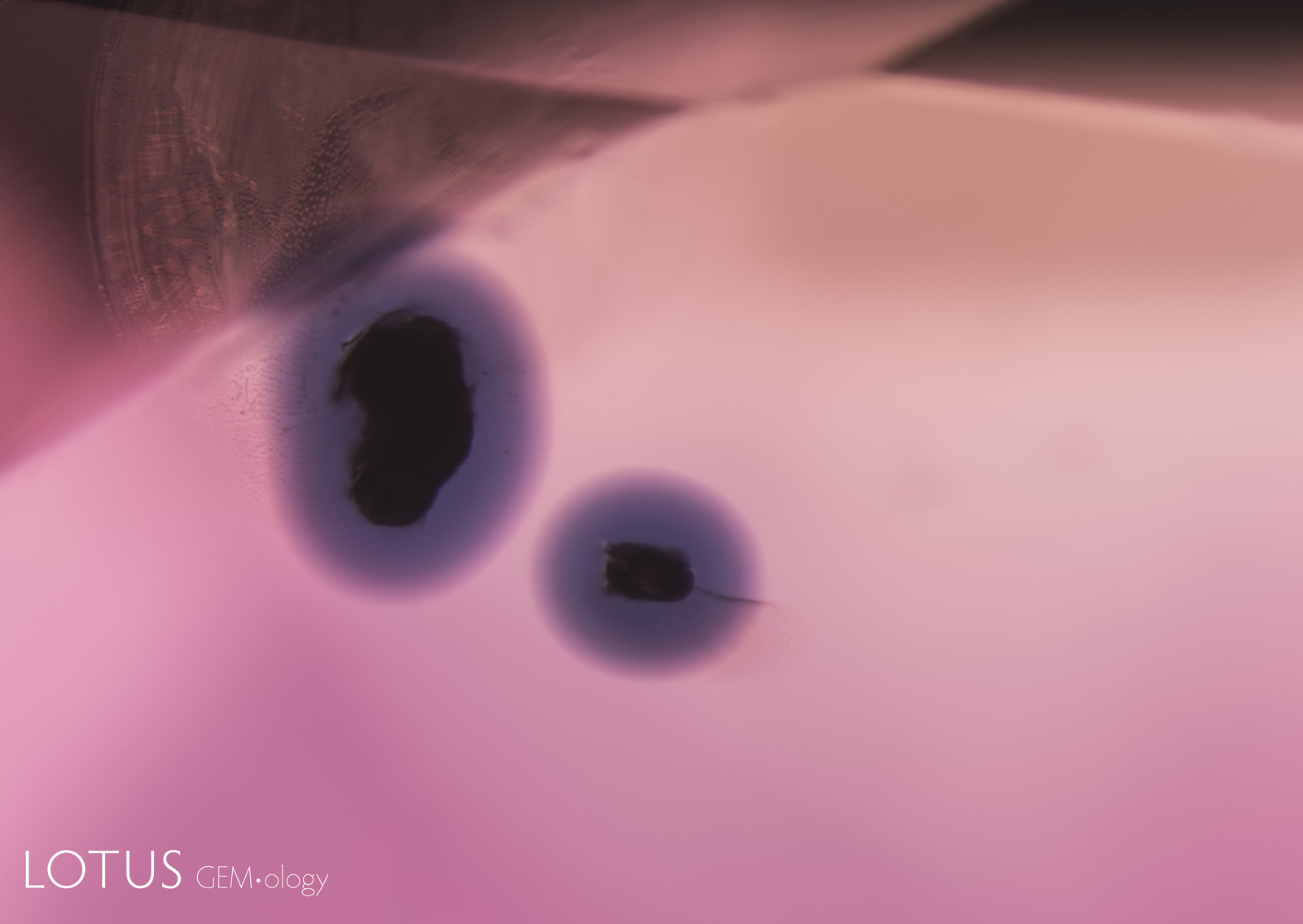

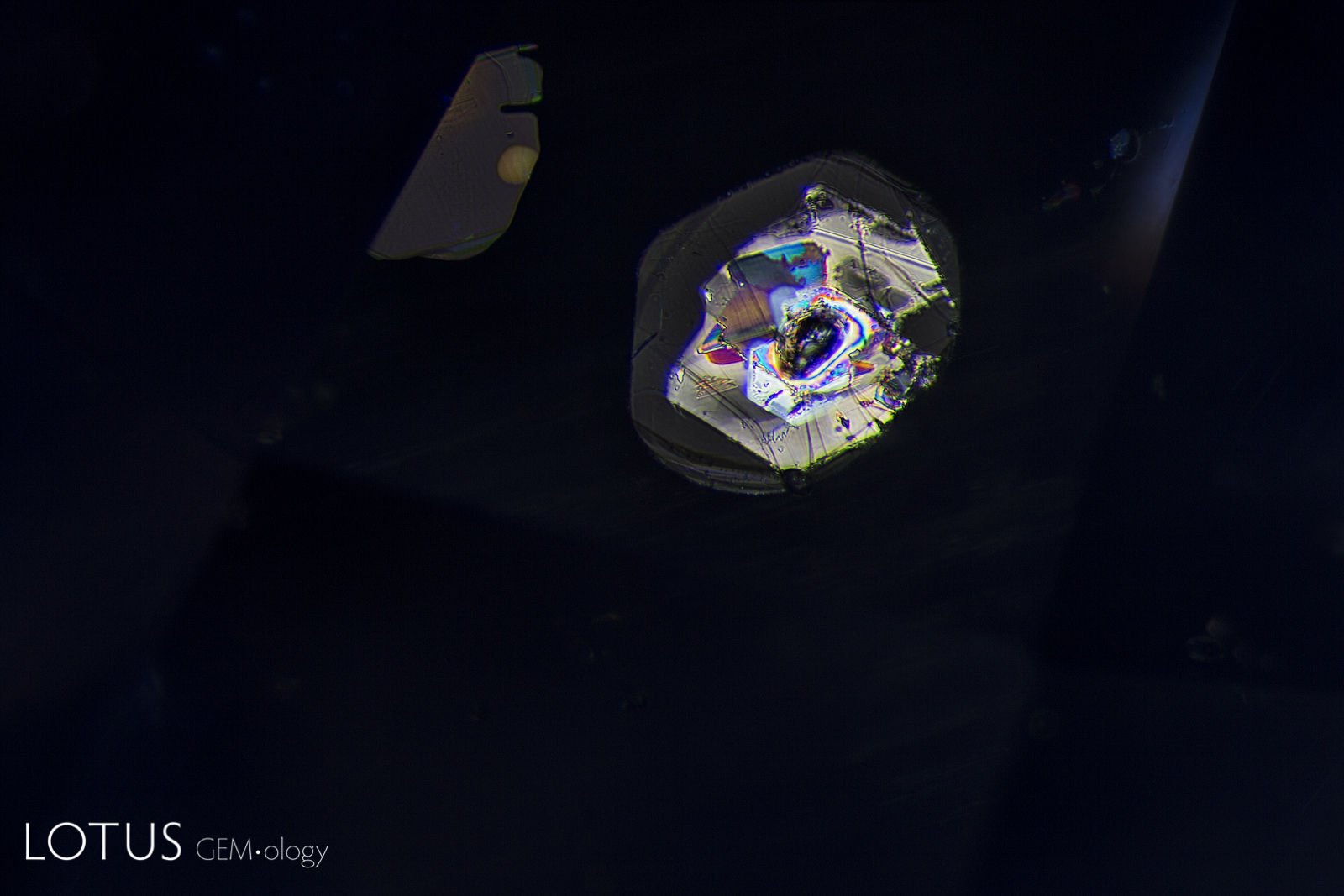

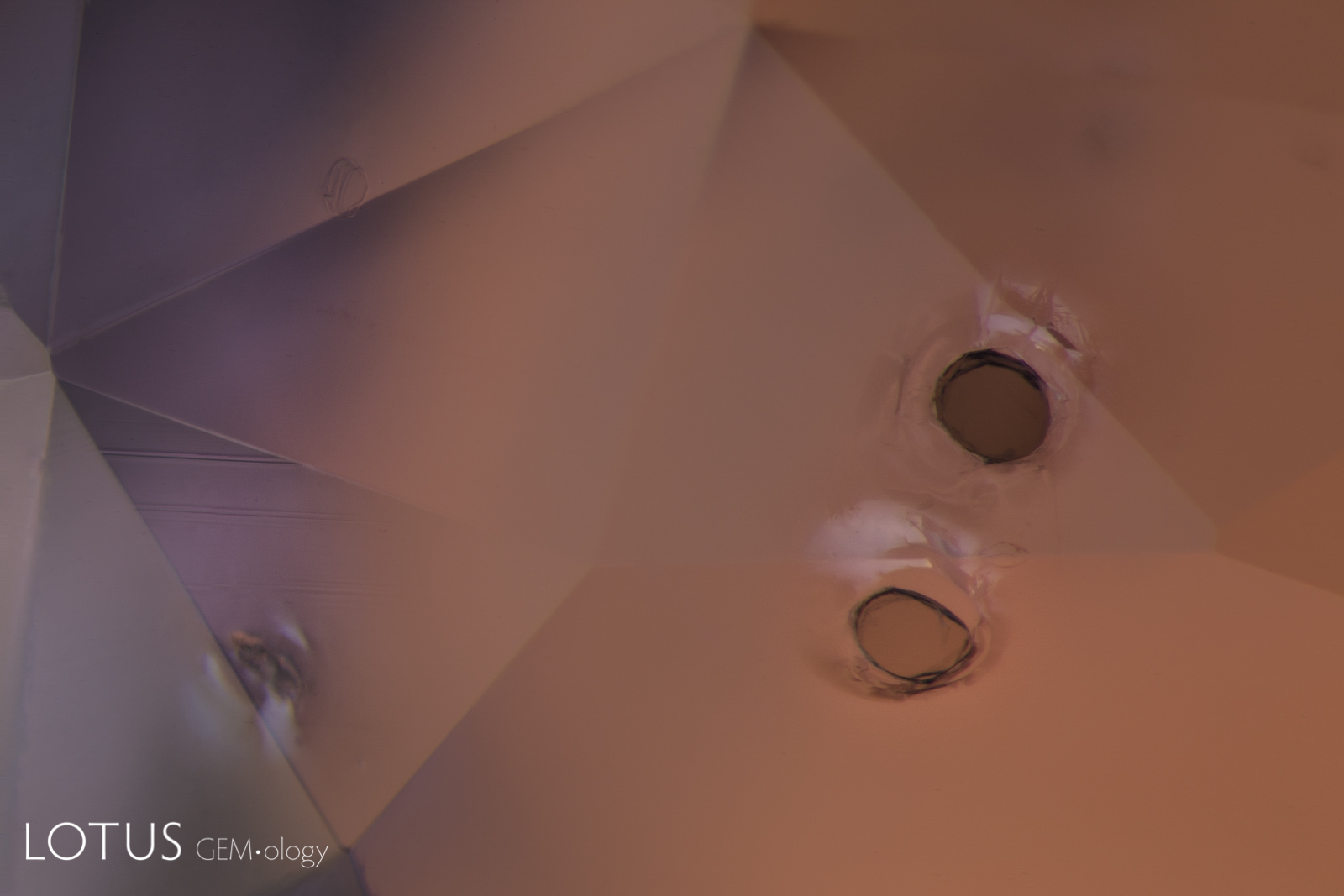

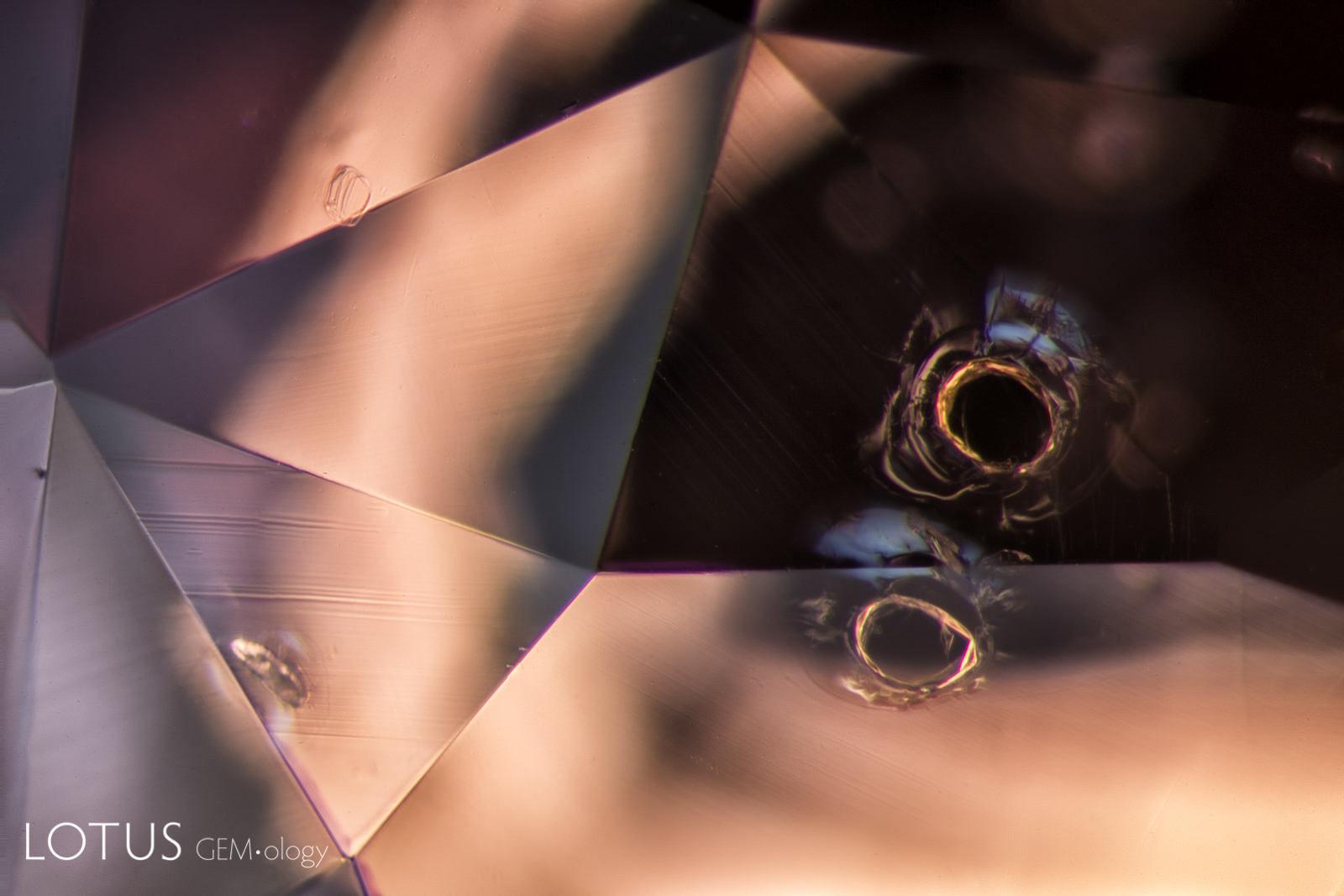

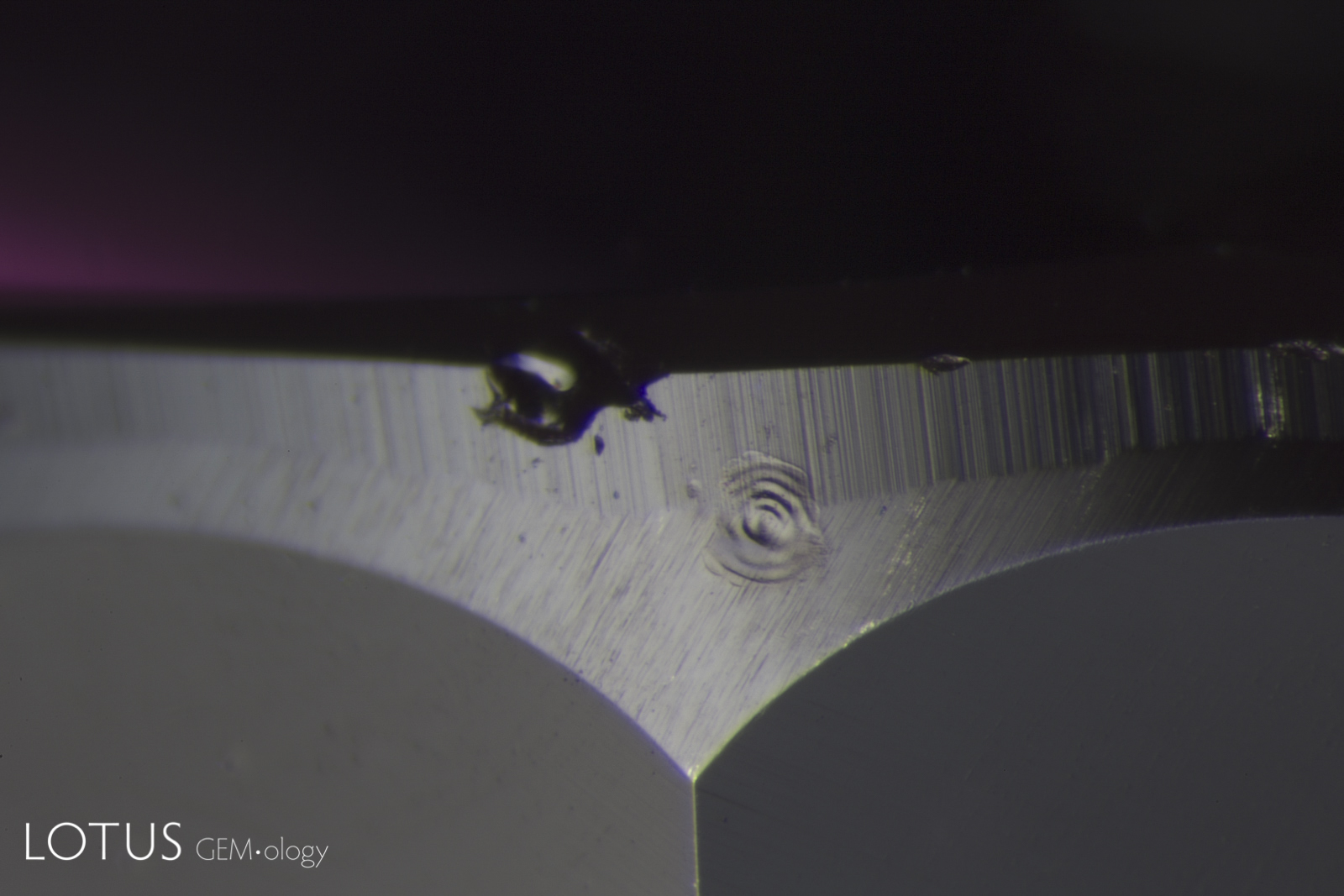

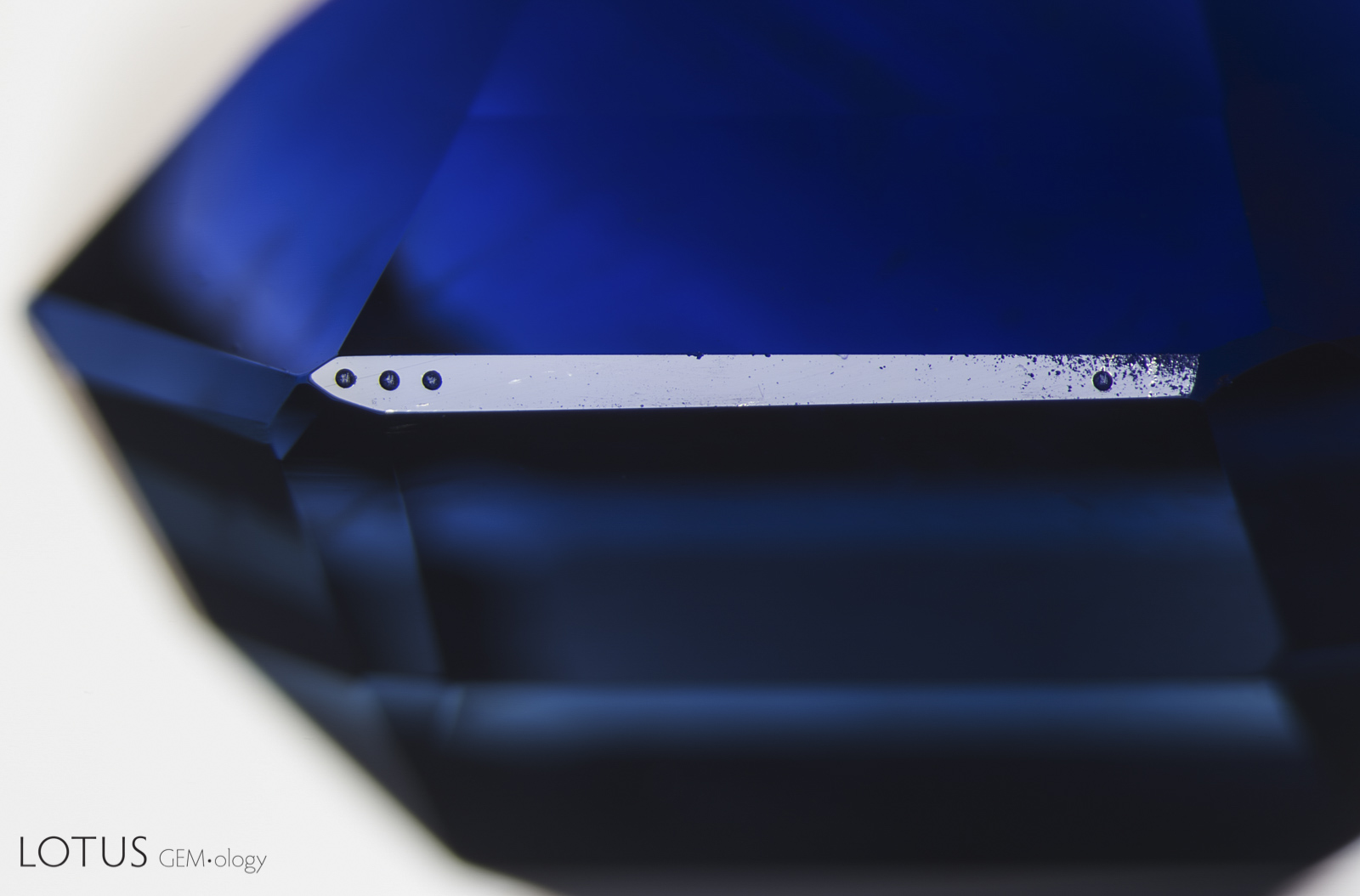

Left: Laser-Induced-Breakdown-Spectroscopy (LIBS) is used by some gem labs to test for beryllium. Unlike Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectroscopy (LA-ICPMS), the surface is actually melted (rather than ablated), producing the circular rippled mark we see in the center of the girdle on the stone at left. |

|