Developing a comprehensive colored stone grading system has been the dream of gemologists since the late 1970's, but despite a number of valient attempts, we are no closer to the goal today than we were four decades ago. This article examines the various problems of colored stone grading, explaining why the challenges are at least an order of magnitude greater than the grading of diamonds.

Much of human activity concerns discretionary ability. The world is not digital—black and white—but infinite shades of gray that undergo continuous change. We are constantly called upon to make qualitative judgments. Such decisions are part of daily life and our “success” on this planet is closely tied to how we deal with these challenges.

As part of our evolutionary progress, society has developed guidelines. While such rules of thumb cannot predict the future of an individual event, if they are based upon the experiences of a large sampling of people, they have utility to the individual over the long haul. But when they are based merely upon faith rather than empirical methods—even if that faith is shared by a majority of others—such beliefs devolve into dogma. And the problem with dogma is that it is, by definition, incontrovertible truth—not subject to question.

There is considerable evidence to suggest that many of today’s religious and cultural dogmas were at one time based on empiricism. For example, the prohibition against eating pork, widespread in many cultures, appears to have grown out of the fact that those who did eat pork became ill at a higher rate. But recent studies suggest this was not the reason. It is now believed the prohibition had nothing to do with disease, but with selfishness. In desert communities, where water and shade were at a premium, it was considered selfish to raise pigs, which required both.

This is a classic example of dogma, which freezes knowledge at a certain point in time, barring future discovery. Thus, despite the fact that later human experience has shown that proper cooking can eliminate the illness-producing components present in pork, the ban remains. What is even more contradictory is that this dogma was spread from desert lands, where it had a certain practicality, to places today where water and shade are in abundance (such as Indonesia).

This is the difference between empirical beliefs, and those based upon faith alone, i.e., those based on observation and first-hand experience, rather than an assumption of truth.

Ruby & sapphire grading: A heretic’s guide

I gotta love for Angela, I love Carlotta, too.

I no can marry both o’ dem, so w’at I gona do?

Thomas Augustine Daly [1871–1948], Between Two Loves

Having now committed one heresy, the discussion of religion, we shall proceed to commit another, the discussion of colored stone grading.

When the lead author (RWH) first entered the gem trade in 1979, certain persons older and wiser advised that colored stones would never be graded in the manner of diamonds. Such cautions did little to dissuade gemologists in their quest to develop colored stone grading systems. James Nelson, in his excellent article on the methods and benefits of colored stone grading (1986), cataloged a variety of trade objections:

- Like the priests who opposed translation of the Latin Bible into common languages, dealers are afraid that colored stone grading will remove their trade advantages, thus cutting the traditional gem dealer out of the picture.

- In a business where the most complicated and expensive piece of equipment is often an electronic balance, traders dislike the thought of having to send their stones out for lab grading.

- Many colored stone dealers abhor the thought that their trade might become like the diamond trade, where stones with lab reports are traded in an indiscriminate manner, in some cases without ever viewing the gem. As a Geneva dealer once told me: “My five-year old son can trade certificate diamonds. It requires no knowledge, no training.”

In the 1997 edition of our book, Ruby & Sapphire, we argued firmly in favor of colored stone grading systems. Now, some 20 years on, we believe quite the opposite, that a system such as used for diamonds is a pipe dream. In what follows, we will describe what has caused this seismic shift in our opinions.

A brief history of colored stone grading

Grading systems are as old as the gem trade itself. Witness ancient India’s Garuda Purana (Shastri, 1978), dating back as far as 400 AD, which classified the then-known gems into categories on the basis of their characteristics. Over the succeeding centuries, these systems have been steadily refined. Diamond grading systems made their appearance in the 1950s, but modern attempts at colored stone grading date only from the late 1970s. Despite a number of attempts, such grading “systems” have never caught on.

In 1997, we wrote:

The key to developing a successful colored stone grading system will be in creating a language useful for communicating the overall appearance of a gemstone. Once a gem is adequately described, it is then up to the marketplace to determine relative value.

Richard Hughes, 1997, Ruby & Sapphire

This brief paragraph contains the horns of the dilemma: “…creating a language useful for communicating the overall appearance of a gemstone.”

How does one describe a complex visual image? Take a cloud in the sky. Imagine trying to create a vocabulary that would even come close to describing these incredibly complex phenomena. Yes, we can and do classify them in certain broad ways (cumulus, nimbus, etc.), but that does nothing to really explain what our eyes see.

The gem business has been successful in creating broad classification systems that are reasonably robust and of great utility. But we are nowhere close to being able to describe the appearance of a faceted colored gemstone with any degree of specificity, either using the written word, or what is the current Holy Grail, digital media (the GemeWizard being the latest flavor). What is meant by “specificity”? That question was discussed in a letter from a color scientist that we read long ago. The color scientist said:

If a colored stone grading system were to be useful, what would be needed is an array of colors such that, where there is a significant difference in value due to color, the system would contain different colors for each of those value differences.

If only life were so simple.

Before we begin discussing the difficulties of colored stone grading, we need to understand color itself. What follows is how color scientists describe color.

Scientific description of color

To the color scientist, given an opaque, matte-finished object, there are three dimensions of color:

- Hue position: The position of a color on a color wheel, i.e., red, orange, yellow, green, blue and violet. Purple is intermediate between red and violet. White and black are totally lacking in hue, and thus achromatic (‘without color’). Brown is not a hue in itself, but covers a range of hues of low saturation (and often high tone) in the yellow to orange hues. Similarly, pink is not a hue itself, but covers a range of hues of low tone and low to medium saturation in the red and purple hues.

- Saturation (intensity): The richness of a color, or the degree to which a color varies from achromaticity. When dealing with gems of the same basic hue position (i.e., rubies, which are all basically red in hue), differences in color quality are mainly related to differences in tone and saturation. The strong red fluorescence of most rubies (the exception being primarily those from the Thai/Cambodian border region) is an added boost to saturation, supercharging it past other gems that lack the effect.

- Tone (lightness or value): The degree of lightness or darkness of a color, as a function of the amount of light absorbed. White (or colorless) would have 0% tone and black 100%. At their maximum saturation, some colors are naturally darker than others. For example, a rich violet is darker than even the most highly saturated yellow, while the highest saturations of reds and greens tend have similar tones.

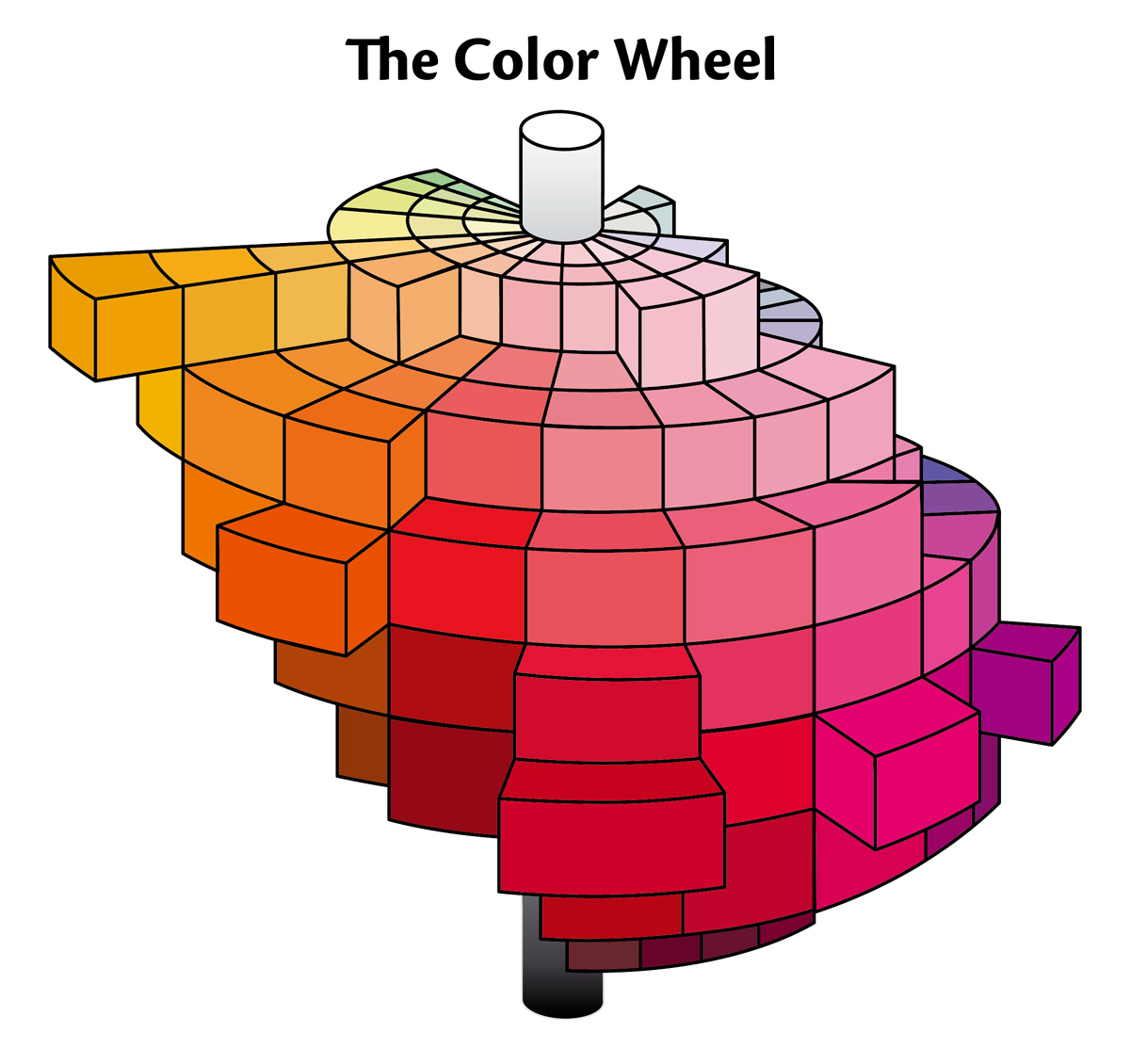

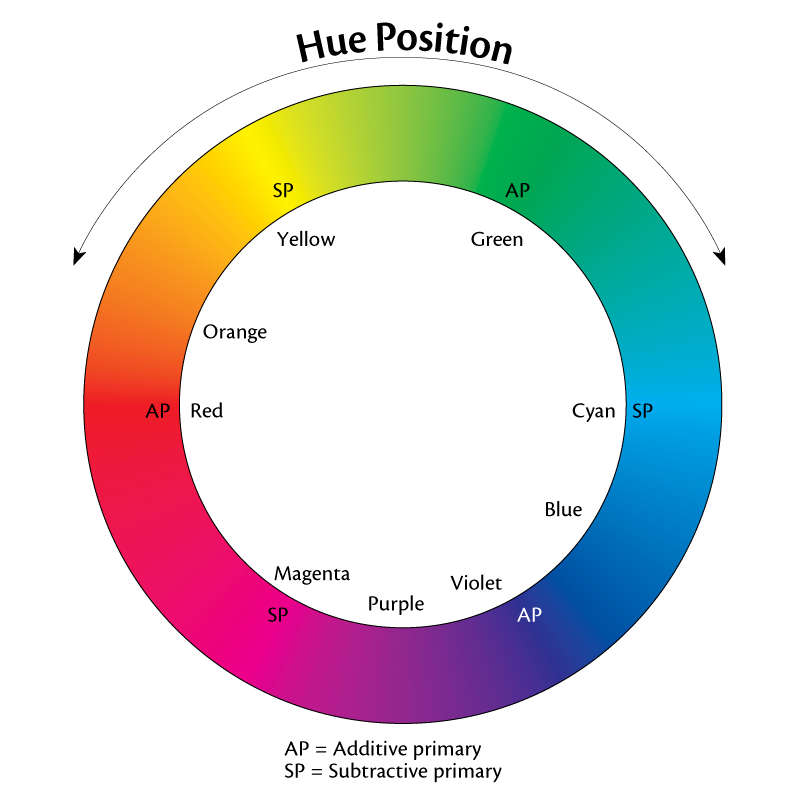

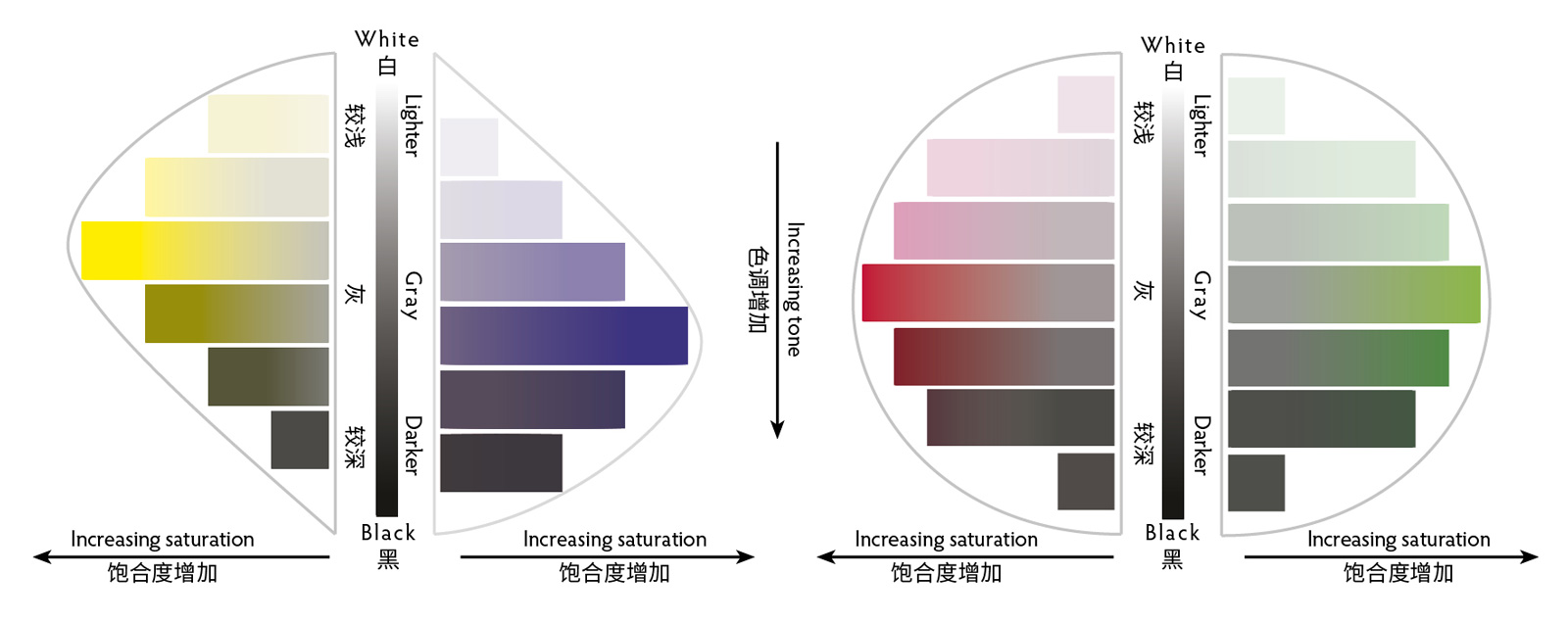

Figure 1 is a simplified illustration of the three dimensions of color:

|

|

|

|

Figure 1. The three dimensions of color

Top left: Three-dimensional view of a color solid. Illustration courtesy of Minolta USA

Top right: Hue position is illustrated by the color wheel, representing a vertical slice through the color solid (the center is not shown). Mixing equal amounts of the three additive primaries (red-orange, violet, green) produces white, while equal mixtures of subtractive primaries (cyan, magenta, yellow) results in black.

Below: Vertical slices through the color solid along the yellow-violet and green-red axes. Saturation increases horizontally from the center, while lightness/darkness varies along the vertical axis. Note that the highest saturation of yellow is naturally much lighter than that for violet, while the highest saturations of red and green share a similar lightness.

Differences between gems and opaque, matte-finished objects

Now let's examine this in terms of faceted rubies and sapphires, which possess several more dimensions of complexity (most of which are not present in colorless diamonds):

- Transparent: Gems are transparent, rather than opaque.

- Faceted: Not only are they transparent, but they are also cut with facets that change the color displayed, even across a single facet.

- Out-of-gamut saturation: Because of their transparency, gems can reach saturations far higher than opaque, matte-finished objects.

- Asymmetrical cutting: The facets are often cut with only crude symmetry, meaning that as the stone is rotated or tilted, those colors will change in an asymmetrical fashion. In addition, many rubies and sapphires have large naturals that can impact appearance in an asymmetrical fashion. By contrast, when compared with colored stones, diamonds are often cut to extraordinary degrees of symmetry.

- Inclusions: Colored stones often contain eye-visible inclusions that can affect transparency and/or reflect light in a specular fashion. Such inclusions may occur in almost any direction and so can be invisible in one direction, while having major impact on appearance in another. Obviously the color of inclusions can also impact overall color.

- Pleochroism: Colored stones may be pleochroic, meaning that their color can vary with crystallographic direction. In the case of ruby and sapphire, this has a subtle, but noticeable, effect on appearance.

- Color zoning: Colored stones often display a degree of color zoning. Depending on the extent, this can have a huge impact on appearance, and is often visible from certain directions, but not others. Sometimes the color zoning is a combination of a single color and colorless zones; at other times, it is a mixture of two (or even more) different colors. Their interaction further complicates matters.

With the exception of transparency, virtually none of these factors are present in diamond, which is one reason why diamond grading is so simple by comparison. In addition, the diamond grading system deliberately (and deceptively) reduces complexity by grading “body color” (color seen through the back), rather than trying to sort stones based on actual face-up appearance (where differences in color are often invisible).

All of the above combine to make describing the appearance of faceted colored stones several orders of magnitude more complex than opaque, matte-finished objects, and again, ever more complex than diamond. Colored gemstones do not display a single “color.” Instead they are three dimensional mosaics of color, and those colors change if the stone, eye or light source changes.

But enough of arcane, academic argument. If you want to truly understand the difficulties of accurately classifying (grading) rubies and sapphires into groups where, when there is a significant difference in value, the system would contain different grades for each of those value differences, take a large parcel of ruby or sapphire that a dealer has pre-sorted and get to it.

I (RWH) have actually done this. Since the 1997 edition of this book, I’ve supervised the sorting of millions of carats of colored stones of various types. This includes over a million carats of Australian sapphire alone.

In the case of the Australian sapphire, even though many were cut to calibrated sizes and shapes, it was still devilishly difficult to match stones. The greatest problem was that stones might match in one position, but when the stones were rotated to a different position, they no longer matched. And this was for stones that were commercial grade round brilliant cuts of less than one carat. Larger sizes were even more difficult to match.

All of this was done under standardized lighting with standardized viewing geometry. Change the light source or geometry and guess what happens? The stones no longer match.

Master stones?

What this means for colored stone grading is that assembling sets of natural master stones to grade color (à la diamond) is practically impossible. Rudimentary sets can be created, but sets with any degree of precision are beyond our itellectual and technological reach.

Some have suggested that masters be created from plastics or glasses. Such sets provide a crude framework, but nowhere near the precision needed to meet our stated requirement:

When there is a significant difference in value, the system would contain different grades (and thus master stones) for each of those value differences.

Glasses and plastics are singly refractive and do not match the refractive indices and dispersions of the natural stone. What about synthetics? They match RI and dispersion, but do not have the zoning and textures displayed by many rubies and sapphires. Nor do they display the subtle differences in color of the natural stones, in part because the color of natural rubies and sapphires is often the result of mixed chromophores (extensively detailed in Chapter 4 of Ruby & Sapphire: A Gemologist's Guide).

Digital imaging systems?

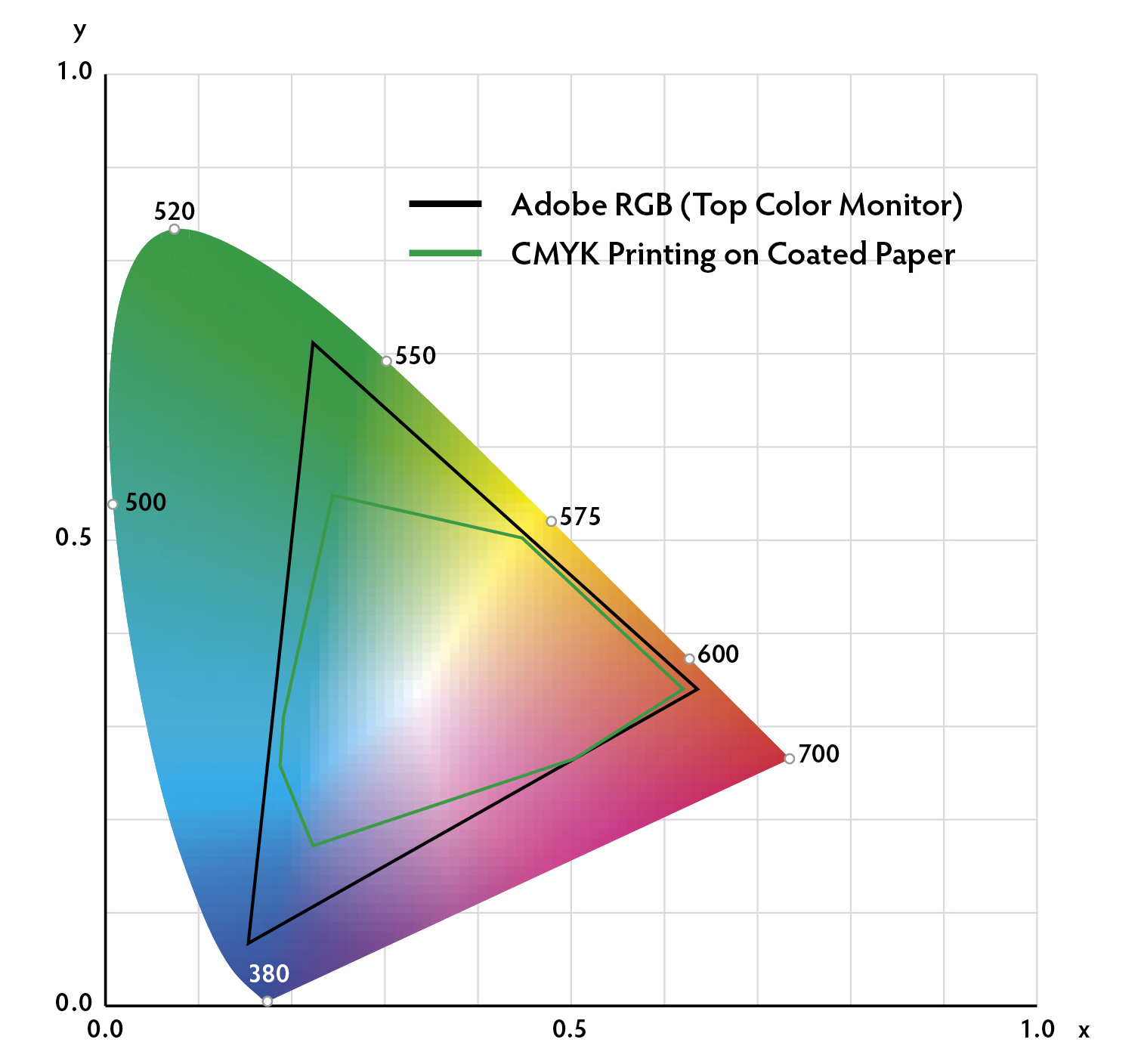

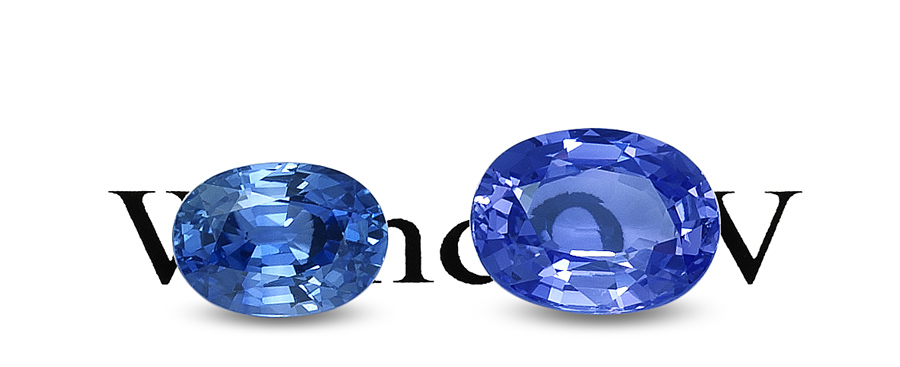

Okay, if we cannot use glass, plastic or synthetics, what about digital imaging? This has also been attempted, but fails for the simple reason that, even with the finest cameras and best computer monitors, many of the highest saturation colors (meaning where the most money is involved) are out-of-gamut for each of the devices. In other words, our eyes can see differences, but those devices cannot reproduce those colors (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The CIE (International Commission on Illumination, a.k.a. Commission International de l’Éclairage) chromaticity diagram is used to specify the exact position of all colors visible to the human eye. Note that a computer monitor (represented by Adobe RGB) can display only the colors inside the black line. The colors that can be printed using the standard CMYK printing process is even further restricted to those colors inside the green line. Many rubies and sapphires feature colors outside of both of these “gamuts.” Thus judgment must be made by personal examination, rather than via printed photos or digital images.

Figure 2. The CIE (International Commission on Illumination, a.k.a. Commission International de l’Éclairage) chromaticity diagram is used to specify the exact position of all colors visible to the human eye. Note that a computer monitor (represented by Adobe RGB) can display only the colors inside the black line. The colors that can be printed using the standard CMYK printing process is even further restricted to those colors inside the green line. Many rubies and sapphires feature colors outside of both of these “gamuts.” Thus judgment must be made by personal examination, rather than via printed photos or digital images.

The question of taste

One of the first arguments we heard against colored stone grading was something that took us decades to understand. Experienced dealers told us that you cannot dictate taste. The coin finally dropped for RWH when working on Vlad Yavorskyy’s Terra Spinel (Yavorskyy & Hughes, 2010) book. He asked to include some photos of gray spinel in the book. RWH asked why? Vlad's response left him stunned: “I like gray.” Finally RWH understood what his elders had tried to teach him so long ago. You cannot dictate taste. You cannot tell people what they should like.

In effect, colored stone grading is akin to telling people vanilla is better than chocolate. It’s dictating taste—an attempt to reduce years or decades of experiences, millennia of conditioning and billions of differences in the brains and bodies of each of us into a simple numerical formula.

Examine the people in Figure 3. We think all would agree that they are an attractive group. But we now understand that trying to arrange them in some sort of order of “attractiveness” is not just impossible, but stupid, because “attraction” is a personal taste.

We hope by now to have convinced readers of the grave difficulties in creating systems for colored stone grading. But this does not mean that we cannot apply some broad rules for classifying gems according to quality. What follows is an attempt to do just that.

Figure 3. Which of the above people is most attractive? Most would agree that there is no right or wrong answer, that this is something an individual must personally decide. But when it comes to ranking colored stones, many gemologists (and some dealers) believe it is feasible to create such a ranking. Photos: Getty Images/iStockphoto

Figure 3. Which of the above people is most attractive? Most would agree that there is no right or wrong answer, that this is something an individual must personally decide. But when it comes to ranking colored stones, many gemologists (and some dealers) believe it is feasible to create such a ranking. Photos: Getty Images/iStockphoto

The elements of quality

Quality is determined by reference to the so-called 3 C’s: color, clarity and cut. While these factors are well defined for diamond, no universally-accepted system exists for colored gems. The following is based on the author’s own extensive experience.

Color and appearance in colored gemstones

As previously described, to the color scientist, given an opaque, matte-finished object, there are three dimensions to color, hue position, saturation and tone. But with gems, we are not dealing with opaque, matte-finish objects of uniform color. Thus it is not enough to simply describe hue position, saturation and tone. We must also describe the color coverage, scintillation and dispersion.

- Color coverage: Differences in inclusions, transparency, fluorescence, cutting, zoning and pleochroism can produce vast differences in the color coverage of a gem, particularly one that is faceted. A gem with a high degree of color coverage is one in which color of high saturation is seen across a large portion of its face in normal viewing positions. Tiny light-scattering inclusions, such as rutile silk, can actually improve coverage, and thus appearance, by scattering light into areas it would not otherwise strike. The end effect is to give the gem a warm, velvety appearance (Kashmir sapphires are famous for this). Red fluorescence in ruby boosts this still further.

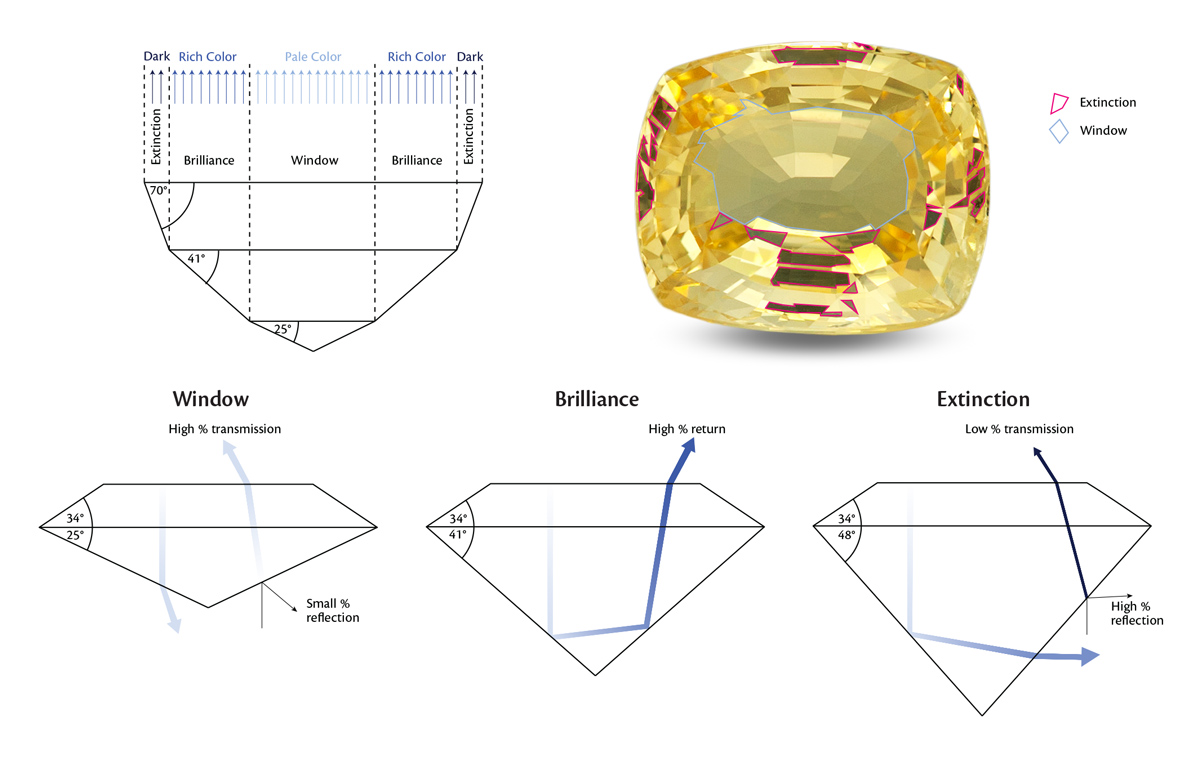

Proper cutting is vital to maximize color coverage. Gems cut too shallow permit only short light paths, thus reducing saturation in many areas. Such areas are termed windows. Those cut too deep allow light to exit the sides, creating dark or black areas termed extinction. Areas which allow total internal reflection will display the most highly saturated colors. These areas are termed brilliance.

Color zoning can also reduce color coverage. Ideally, no zoning or unevenness should be present.

Pleochroism is sometimes noticeable in ruby and sapphire. It typically appears as two areas of lower intensity and/or slightly different hue on opposite sides of the stone. This is most notable when the table facet lies parallel to the c axis.

In summary, a top-quality gem displays the hue of maximum saturation across a large percentage of its surface in all viewing positions. The closer to this ideal, the better its color coverage. - Scintillation (‘sparkle’): This is important in faceted stones. A gem cut with a smooth, cone-shaped pavilion could display full brilliance, but would lack scintillation. Thus the use of facets, which create sparkle as the gem, light or eye is moved. In general, large gems require more facets; small gems should have fewer, since tiny reflections cannot be individually distinguished by the eye (resulting in a blurred appearance).

- Dispersion (‘fire’): This involves splitting of white light into its spectral colors as it passes through two non-parallel surfaces (such as a prism). The dispersion of corundum is so low (0.028) and the masking effect of the rich body color so high, that it is generally not a factor in ruby and sapphire evaluation.

Judging tone & saturation

One of the greatest challenges in ruby and sapphire grading is determining tone and saturation. Unlike printed color chips, faceted gems do not display uniform colors. Thus tone and saturation can vary greatly across the stone, from one facet to another and from one stone or eye position to another.

Generally speaking, saturation is always judged by reference to the brilliance flashes, but even these may show significant variation. This is further complicated by stones that are so poorly cut that the color coverage is 20% or less. What to do in these situations? There is no consensus, which is one reason why colored stone grading is so difficult.

By contrast, tone is judged not just on the brilliance flashes, but on the stone’s overall lightness/darkness. Sample stones are shown in Figure 5.

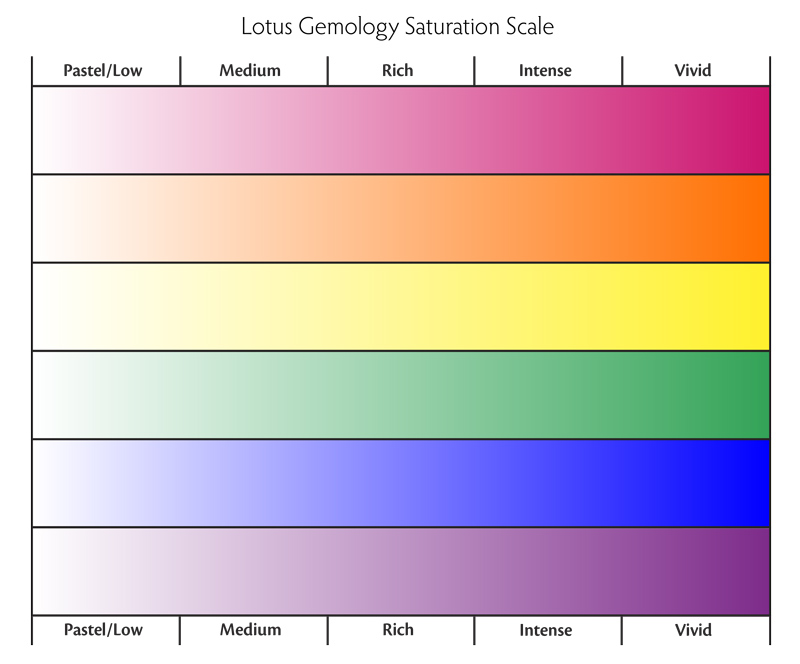

Figure 4. The Lotus Gemology Saturation Scale. Note that the highest saturations are out-of-gamut, and so cannot be shown on a printed scale such as this. Saturation of faceted gems is, in most cases, judged by reference to the saturation of the average brilliancy flashes.

Figure 4. The Lotus Gemology Saturation Scale. Note that the highest saturations are out-of-gamut, and so cannot be shown on a printed scale such as this. Saturation of faceted gems is, in most cases, judged by reference to the saturation of the average brilliancy flashes.

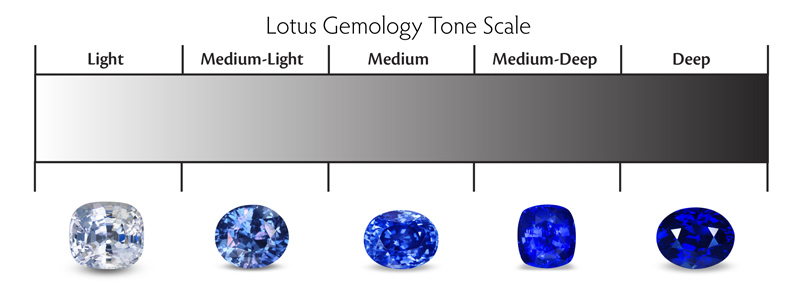

Figure 5. The Lotus Gemology Tone Scale. Note that, unlike saturation, tone is judged by the overall lightness/darkness of the stone.

Figure 5. The Lotus Gemology Tone Scale. Note that, unlike saturation, tone is judged by the overall lightness/darkness of the stone.

Judging clarity

Clarity is judged by reference to inclusions. Magnification can be used to locate inclusions, but with the exception of inclusions which might affect durability, only those visible to the naked eye should influence the final grade.

There are several key factors in judging clarity:

- Visibility: How prominent the inclusions are.

- Size: Smaller inclusions are less distracting, and thus, better.

- Number: Generally, the fewer the inclusions, the better.

- Contrast: Inclusions of low contrast (compared with the gem’s RI and color) are less visible, and thus, better.

- Location: Inclusions in inconspicuous locations (i.e., near the girdle rather than directly under the table facet) affect value less. Similarly, a feather perpendicular to the table is less likely to be seen than one lying parallel to the table.

Affect on durability

- Type: Unhealed cracks may not only be unsightly, but also lower a gem’s resistance to damage. They are thus less desirable than a well-healed fracture. As already mentioned, tiny quantities of exsolved silk may actually improve a gem’s appearance, and thus, value.

- Location: A crack near the culet or corner increases the chances of breakage compared with one deeper inside the gem. Similarly, an open fracture on the crown is more likely to chip than one on the pavilion.

Among the problems of existing colored stone grading systems is that the model chosen is based on diamond. While diamond does share a number of quality factors with ruby and sapphire, others are partly or wholly inappropriate. For example, beauty in diamond is largely a function of the material’s brilliance and dispersion (‘fire’). Any inclusions which alter the path of light could be detrimental to a diamond’s appearance.[1] Perfect clarity is thus the ideal. As described above, perfect clarity is not necessarily the ideal for ruby and sapphire. While fractures and most other inclusions do have a detrimental effect on appearance and durability, small quantities of finely dispersed inclusions (such as exsolved rutile silk) can actually improve a richly colored gem’s appearance. The watchword here is small; too much silk decreases transparency by scattering, reducing color saturation, and thus producing a more grayish color.[2]

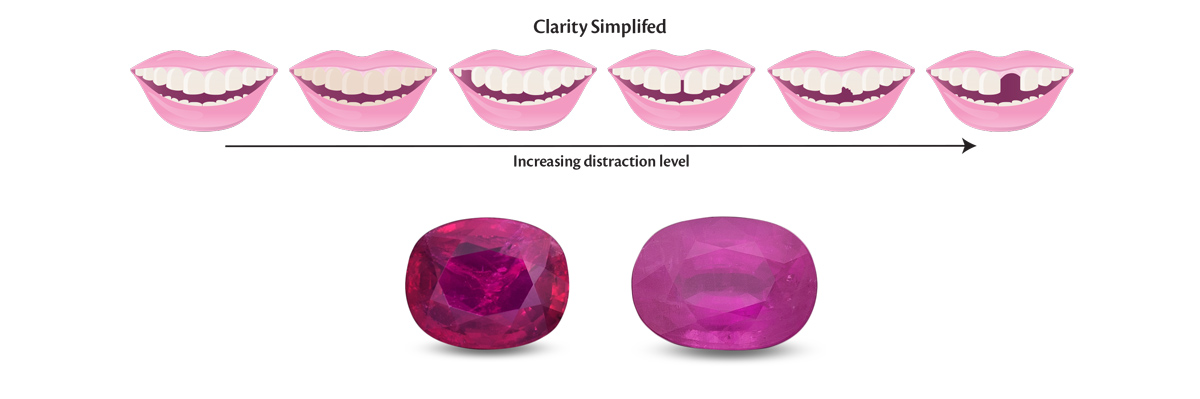

Figure 6. Clarity decisions Clarity can be summarized in a single word: distraction. The degree of distraction can be seen by comparing the smiles above, where it increases as you move to the right. But real life is rarely so simple. With the two rubies above, each has different types of clarity problems. Choosing between them then becomes a personal preference. Illustration: iStockPhoto.com; gem photos: Wimon Manorotkul

Figure 6. Clarity decisions Clarity can be summarized in a single word: distraction. The degree of distraction can be seen by comparing the smiles above, where it increases as you move to the right. But real life is rarely so simple. With the two rubies above, each has different types of clarity problems. Choosing between them then becomes a personal preference. Illustration: iStockPhoto.com; gem photos: Wimon Manorotkul

Judging cut ('make')

The function of the cut is to display the gem’s inherent beauty to the greatest extent possible. Since this involves aesthetic preferences upon which there is little agreement, such as shape and faceting styles, this is the most subjective of all aspects of quality analysis.

Evaluation of cut involves five major factors:

- Shape: This describes the girdle outline of the gem, i.e. round, oval, cushion, octagonal, etc. While preferences in this area are largely a personal choice, due to market demand and cutting yields, certain shapes fetch a premium. For ruby and sapphire, ovals and cushions are the norm. Rounds and emerald shapes are more rare, and so can receive a premium from about 10–20% above the oval price. Pears and marquises are less desirable, and so trade about 10–20% less than ovals of the same quality. The shape of a cut gem almost always relates to the original shape of the rough. Thus the prevalence of certain shapes, such as ovals, which allow greatest weight retention.

- Cutting style: The cutting style (facet pattern) is also a rather subjective choice. Again, because of market demand, manufacturing speed and cutting yields, certain styles of cut may fetch premiums. The mixed cut (brilliant crown/step pavilion) is the market standard for ruby and sapphire.

- Proportions: The faceted cut for ruby and sapphire is designed to create maximum brilliance and scintillation in the most symmetrically pleasing manner. Faceted gems feature two parts, crown and pavilion. The crown’s job is to catch light and create scintillation (and dispersion, in the case of diamond), while the pavilion is responsible for both brilliance and scintillation. Generally, when the crown height is too low, the gem lacks sparkle. Shallow pavilions create windows, while overly deep pavilions create extinction. Again, proportions often are dictated by the shape of the rough material. Thus to conserve weight, Sri Lankan material (which typically occurs in spindle-shaped hexagonal bipyramids) is generally cut with overly deep pavilions, while Thai/Cambodian rubies (which occur as thin, tabular crystals) are often far too shallow.

- Depth percentage: In attempting to quantify a gem’s proportions, reference is often made to depth percentage. This is calculated by taking the depth and dividing it by the girdle diameter (or average diameter, in the case of non-round stones). The acceptable range is generally 60–80%.

- Length-to-width ratio: Another measurement that is used for non-round stones is the length-to-width ratio. Overly narrow or wide gems of certain shapes are generally not desirable.

Symmetry

Like any finely-crafted product, well-cut gems display an obvious attention to detail. A failure to take proper care evidences itself in a number of ways, including the following:

- Asymmetrical girdle outline

- Off-center culet or keel line

- Off-center table facet

- Overly narrow/wide shoulders (pears and heart shapes)

- Overly narrow/deep cleft (heart shapes)

- Overly thick/thin girdle

- Poor crown/pavilion alignment

- Table not parallel to girdle plane

- Wavy girdle

Figure 7. Faceted gemstones display a combination of reflections largely determined by the angles of the pavilion (rear) facets. When pavilion angles are too shallow, light from above leaks through the bottom, creating a “window” (so-called because you can see through the stone). In contrast, if pavilion angles are too deep, light leaks out the side. Light from below also cannot enter, creating dark areas of “extinction.” Only when the angles are correct, does light return to the eye. These intensely colored areas are termed brilliance and in the yellow sapphire shown above, they are all the areas not outlined. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Figure 7. Faceted gemstones display a combination of reflections largely determined by the angles of the pavilion (rear) facets. When pavilion angles are too shallow, light from above leaks through the bottom, creating a “window” (so-called because you can see through the stone). In contrast, if pavilion angles are too deep, light leaks out the side. Light from below also cannot enter, creating dark areas of “extinction.” Only when the angles are correct, does light return to the eye. These intensely colored areas are termed brilliance and in the yellow sapphire shown above, they are all the areas not outlined. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Finish

Lack of care in the finish department is less of a problem than the major symmetry defects above, because it can usually be corrected by simple repolishing. Finish defects include:

- Facets not meeting at a point

- Misshapen facets

- Rounded facet junctions

- Poor polish (obvious polishing marks or scratches)

While these guidelines may be useful, one must not become a slave to them. In essence, the cut should display the gem’s beauty to best advantage, while not presenting mounting or durability problems. If the gem is beautifully cut, things such as depth percentage or length-to-width ratio matter not one bit. What works, works.

Figure 8. Differences between brilliant (left) and shallow (right) gems are vividly revealed above, with the stone on the right showing an obvious window. Just because a gem is shallow does not mean it is poorly cut. The job of the cutter is to return the most expensive stone possible, not necessarily the most beautiful. At times that means saving weight. The lapidary faces a constant battle between weight and beauty. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Figure 8. Differences between brilliant (left) and shallow (right) gems are vividly revealed above, with the stone on the right showing an obvious window. Just because a gem is shallow does not mean it is poorly cut. The job of the cutter is to return the most expensive stone possible, not necessarily the most beautiful. At times that means saving weight. The lapidary faces a constant battle between weight and beauty. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Influence of lighting on color

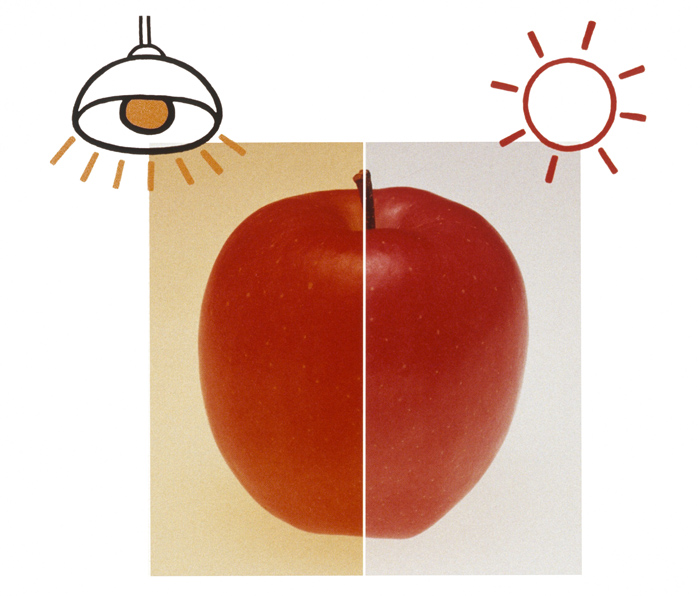

With any colored gemstone, the color seen depends on the light source used to illuminate it. Over time, gem dealers have come to rely on skylight (as opposed to direct sunlight) for their gem buying. Its major advantage is its strength, which ruthlessly reveals flaws. The quantity of light coming through even a modest-sized window is far greater than the strongest, color-balanced fluorescent tube (or tubes). Another factor appears to be the large radiating area, when compared with most artificial lights.

Figure 9. Lighting can have a dramatic effect on the appearance of any colored gem. Incandescent lighting (left) is rich in red, orange and yellow wavelengths and thus pushes an object’s color in that direction. In contrast, skylight (right) is more balanced, pushing the color in the opposite direction. Illustration: Minolta

Figure 9. Lighting can have a dramatic effect on the appearance of any colored gem. Incandescent lighting (left) is rich in red, orange and yellow wavelengths and thus pushes an object’s color in that direction. In contrast, skylight (right) is more balanced, pushing the color in the opposite direction. Illustration: Minolta

Latitude may also affect a stone’s color, simply because skylight is stronger in the tropics. As a result, gems bought in the tropics will appear slightly darker when taken to more temperate climes. It is a slight, but nevertheless, noticeable difference. Surprisingly, north skylight (or south skylight in the southern hemisphere) is actually stronger on cloudy days.

Another factor is the Purkinje shift. In bright light, the eye is more sensitive to red; conversely, in dim light the eye is more sensitive to blue-violet light. Thus the color of blue sapphires would be slightly enhanced in dim lighting.

The question of north skylight

North daylight (skylight, not direct sunlight) has become the standard, because it produces the least glare, but blind adherence to such gemological dogma is just as bad as blind adherence to religious dogma. If you live north of the Tropic of Cancer (Europe, North America, Japan, China, etc.), north skylight will provide the least glare year round, because the sun always passes through the southern portion of the sky. This is especially true the farther north one goes. The opposite holds true for those who reside south of the Tropic of Capricorn (in the southern hemisphere), where the least glare is found using south skylight.

What about those who live in the tropics? If they are north of the equator, north skylight is best, except from May to July, when south skylight is preferred. For the tropics south of the equator, south skylight is best, except from November–January, when north skylight is preferred. And if you live right on the equator, use north skylight from October–February, and south skylight from April–August. During March and September, either north or south skylight can be used.

Time of day

Even skylight changes throughout the day. Generally speaking, rubies (and other red stones) look best during the midday hours. Sapphires, in contrast, look best in the early morning or late afternoon. If you are buying, this means that rubies should be purchased early or late in the day, while sapphires are best bought near midday, thereby preventing a surprise when the stone is examined under another lighting condition.

The above is in contrast to what is often reported. While direct sunlight is far more red at sunrise and sunset, the skylight is actually more blue. Since we use skylight, not direct sunlight, to illuminate gems, blue color will be enhanced early and late in the day. Similarly, the skylight at noon is less blue, thus enhancing the color of rubies in the middle of the day.

Weather and pollution

How might clouds or pollution affect color? Heavily-polluted or cloudy skies will result in more grayish (less blue) skylight, thus improving the appearance of rubies (as opposed to sapphires).

Figure 10. Natural light is not constant in spectral composition, but varies according to latitude, time of day, cloud and pollution conditions and whether or not one is using direct sunlight or skylight.

Figure 10. Natural light is not constant in spectral composition, but varies according to latitude, time of day, cloud and pollution conditions and whether or not one is using direct sunlight or skylight.

Left: Two ladies in Tibet, silhouetted against a deep blue sky. It is obvious that such skylight would enhance the appearance of blue stones. Top right: Fog in Myanmar’s Mogok Stone Tract. The high moisture content gives the light a grayish cast. Bottom right: Sunset on Sri Lanka’s western coast. While such sunlight could easily enhance the color of red and yellow stones, it should be noted that direct sunlight is rarely used for examining gems. Typically we use skylight, instead. Such skylight is actually more blue early and late in the day. Thus blue sapphires will look better at those times. Conversely, when viewed with skylight, rubies will look best around midday, because the skylight is less blue. Photos: R.W. Hughes

Artificial lighting

Some type of artificial light is obviously the answer to neutralize the above factors. Many dealers today do their buying under special daylight lamps designed to simulate true north daylight, with a color temperature of approximately 5000–6100°Kelvin. Generally speaking, while their color balance is similar to north daylight, the fluorescent tubes used suffer from low light output. A 20 watt fluorescent daylight tube at a distance of 30 cm produces about 1000 lux of illumination, while a north-facing window in Bangkok averages 6000 lux.

The answer appears to be short-arc xenon lamps. While rather expensive (compared to fluorescent lamps), they have a continuous output (like daylight), 6000°K color temperature, and produce illumination levels comparable to north daylight.

For an excellent summary of the entire lighting question, see Sersen & Hopkins (1989) and Sersen (1990), from which the above is derived.

Viewing geometry & background

Gems are designed to be mounted in jewelry and viewed from predetermined angles. This is generally face-up, with the gem viewed in a 180° arc from girdle to girdle. Thus it is only logical that all quality determinations be made with the naked eye under the same viewing geometry. It is important that the gem be rotated through 360° in the girdle plane, so that its appearance is seen from all angles, just as it would be when mounted in jewelry. To ensure reproducibility and repeatability, a standardized light source against a standardized, neutral background (white is best) at a standardized distance should be used. The practice in diamond grading of judging body color through the pavilion facets is madness, and has no place in colored stone grading.

Figure 11. When grading gems, viewing geometry, background and controlled lighting are crucial. Here we see Burmese staff sorting rough at Gemfields’ Montepuez ruby mines. Although it is not consistent, natural daylight is still superior to all other light sources, because windows provide lots of lux and a large, diffuse radiating surface. The closest artificial equivalent is a xenon short arc source. While we use these in microscopy at Lotus Gemology, a unit for color grading has still yet to be developed. Photo: E. Billie Hughes, 2015

Figure 11. When grading gems, viewing geometry, background and controlled lighting are crucial. Here we see Burmese staff sorting rough at Gemfields’ Montepuez ruby mines. Although it is not consistent, natural daylight is still superior to all other light sources, because windows provide lots of lux and a large, diffuse radiating surface. The closest artificial equivalent is a xenon short arc source. While we use these in microscopy at Lotus Gemology, a unit for color grading has still yet to be developed. Photo: E. Billie Hughes, 2015

Summary of quality

The appearance of a colored gem is a combination of many separate factors, each of which is related to, and affects, the others. It is precisely the complexity of these intertwined relationships that has bedeviled previous attempts to quantify quality. And yet, every time a dealer buys a gem, a quick mental analysis is made, usually within seconds. In grading any gem, one must be cognizant of, but not become lost in, the details. When all the minutiae have been pored over ad infinitum, ad nauseam, take a step back and simply look at the gem. In the age of high-powered microscopes this may constitute a radical concept, but one which is necessary.

Fine precious stones are comparable to great works of art. Like a painting, to appreciate it, one must view the whole, not just the parts.

Footnotes

- Unfortunately, the current diamond-grading system, largely based on the GIA model, has applied this idea in an overly zealous manner. Thus even a single microscopic inclusion, which in no way affects a diamond’s appearance, removes it from the top clarity category. Many of the upper clarity grades have absolutely no visible difference in naked-eye appearance (see Hughes, 1987, 1991). [back to text]

- Stones which look good from a distance, but upon closer examination exhibit clarity problems, are termed bluff stones. [back to text]

Notes

Portions of this article appeared in 2017's Ruby & Sapphire: A Gemologist's Guide.

References & further reading

- Hughes, R.W. (1987) Diamond grading: does it work? , Gemological Digest, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 1-3; RWHL.

- Hughes, R.W. (1991) The naked eye: A diamond's worst friend. JewelSiam, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 72-75; RWHL*.

- Nelson, J.B. (1986) The colour bar in the gemstone industry. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 20, No. 4, October, pp. 217–237; RWHL*.

- Sersen, W.J. (1990) Buying and selling gems—What light is best? Part II: The options available. Gemological Digest, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 45–56; RWHL*.

- Sersen, W.J. and Hopkins, C. (1989) Buying and selling gemstones—What light is best? Gemological Digest, Vol. 2, No. 4, pp. 13–23; RWHL*.

- Shastri, J.L., ed. (1978) Garuda Purana. Ancient Indian Tradition and Mythology, English translation 1978, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, Vol. 12, Part 1, see pp. 224–246; RWHL*.

- Yavorskyy, V. and Hughes, R.W. (2010) Terra Spinel: Terra Firma. Hong Kong: Yavorskyy Co., 202 pp.; RWHL*.

About the authors

Richard W. Hughes is one of the world’s foremost experts on ruby and sapphire. The author of many books and over 170 articles, his writings and photographs have appeared in a diverse range of publications, and he has received numerous industry awards. Co-winner of the 2004 Edward J. Gübelin Most Valuable Article Award from Gems & Gemology magazine, the following year he was awarded a Richard T. Liddicoat Journalism Award from the American Gem Society. In 2010, he received the Antonio C. Bonanno Award for Excellence in Gemology from the Accredited Gemologists Association. The Association Française de Gemmologie (AFG) in 2013 named Richard as one of the Fifty most important figures that have shaped the history of gems since antiquity. In 2016, Richard was awarded a visiting professorship at Shanghai's Tongji University. 2017 saw the publication of Richard and his wife and daughter's Ruby & Sapphire • A Gemologist's Guide, arguably the most complete book ever published on a single gem species and the culmination of four decades of work in gemology. In 2018, Richard was named Photographer of the Year by the Gem-A, recognizing his photo of a jade-trading market in China, while in 2020, he was elected to the board of directors of the Accredited Gemologists Association and was appointed to the editorial review board of Gems & Gemology and The Australian Gemmologist magazine. In 2022, Richard published Jade • A Gemologist's Guide, while 2024 brought Broken Bangle • The Blunder-Besmirched History of Jade Nomenclature. His jade trilogy was completed in 2025 with his translation of Heinrich Fischer's Nephrite and Jadeite.

Wimon Manorotkul has been involved with gems and gemology since 1979, as a lab gemologist, instructor and photographer. She is an Accredited Gemologist from Bangkok's Asian Institute of Gemological Sciences and for many years directed their lab. Wimon also qualified as a Fellow (with honors) of the Gemmological Association of Great Britain. A skilled gem photographer, her images have been featured in books and magazines around the world, particularly Ruby & Sapphire: A Collector's Guide, along with Ruby & Sapphire: A Gemologist's Guide and Inside Out | GEM• ology Through Lotus-Colored Glasses. Wimon not only photographs gems, jewelry and mineral specimens, but is also an expert photomicrographer. In 2013, she founded Lotus Gemology with her husband, Richard Hughes, and daughter, E. Billie Hughes.

E. Billie Hughes visited her first gem mine (in Thailand) at age two and by age four had visited three major sapphire localities in Montana. A 2011 graduate of UCLA, she qualified as a Fellow of the Gemmological Association of Great Britain (FGA) in 2013. An award winning photographer and photomicrographer, she has won prizes in the Nikon Small World and Gem-A competitions, among others. Her writing and images have been featured in books, magazines, and online by Forbes, Vogue, National Geographic, and more. In 2019 the Accredited Gemologists Association awarded her their Gemological Research Grant. Billie is a sought-after lecturer and has spoken around the world to groups including Cartier and Van Cleef & Arpels. In 2020 Van Cleef & Arpels’ L’École School of Jewellery Arts staged exhibitions of her photomicrographs in Paris and Hong Kong.