This excerpt from Ruby & Sapphire: A Gemologist's Guide (2017) details the ruby and sapphire deposits of Madagascar. Since the mid-1990s, Madagascar has become one of the world's most important sources.

Madagascar Ruby & Sapphire

My first recollection of Madagascar was grade school, where we dutifully learned that a prehistoric fish, long thought extinct, had been fished from the coastal waters of this errant isle. Later, in gemology class, my teacher again brought up the subject of this forgotten land, mentioning that the famous French naturalist, Alfred Lacroix had written a paper about it (Un Voyage au Pays des Béryls). From that moment on, I knew Madagascar not just as something out of a Jules Verne novel, but as the “Beryl Island.” The following is based on the author’s 2005, 2010 and 2016 visits, along with various published sources.

Map of Madagascar, showing the location of major ruby and sapphire mines and major roads. Click on the map for a larger image.

Map of Madagascar, showing the location of major ruby and sapphire mines and major roads. Click on the map for a larger image.

Island at the end of the universe

The Island of Madagascar is an anomaly in many respects. While lying just 400 km from the coast of Africa, it was not settled until roughly 2000 years ago, and not by Africans, but by adventurous sailors from the Malayo-Indonesian Archipelago, some 6400 km to the east. Today the country’s human population is a tumultuous stew spiced with Malay, African, Arab, French, Chinese and Indian ingredients.

Rough sapphire for sale at Antsoa, south of Ilakaka. Photo: R.W. Hughes, 2016. Click on the photo for a larger image.

Rough sapphire for sale at Antsoa, south of Ilakaka. Photo: R.W. Hughes, 2016. Click on the photo for a larger image.

Madagascar has long been recognized as one of the most biologically diverse spots on the planet. The following will give you some perspective:

- While the California-sized island makes up just 0.4% of the earth’s total landmass, its plant and animal species make up roughly ten times more of the planet’s total.

- 80% of Madagascar’s species are endemic, meaning they are found nowhere else on earth.

- Although Madagascar occupies only about 1.9% of the land area of the African region, it has more orchids than the entire African mainland and is home to about 25% of all African plants.

- Close to 100% of all lemur species are found only in Madagascar.

Madagascar owes its biological diversity to geology. Over 165 million years ago, the island was a land-locked plateau at the center of the supercontinent, Gondwanaland. At this time, giant reptiles roamed the earth, while flowering plants and birds were first beginning to appear. Gondwanaland subsequently broke up, leaving Madagascar like a castaway in the Indian Ocean, marooning many of these ancient species. These were further pollinated by plants, animals and humans flying, drifting, swimming, sailing or blowing onto the island, creating a magnificent menagerie unlike any other on the planet.

And what of Madagascar’s spectacular gem diversity? A quick glance at a map of Gondwanaland provides the answer. Before the breakup of that landmass, Madagascar’s nearest neighbors were East Africa, Southern India and Sri Lanka. These regions represent some of the richest gem deposits on the planet. Madagascar lies smack-dab in the middle of precious stone nirvana.

Pit mining for sapphire near Manambo, just south of Ilakaka, Madagascar. Photo: R.W. Hughes, 2016. Click on the photo for a larger image.

Pit mining for sapphire near Manambo, just south of Ilakaka, Madagascar. Photo: R.W. Hughes, 2016. Click on the photo for a larger image.

History

Madagascar has long held a reputation as a source of precious stones. In 1547, Captain Jean Fonteneau visited the island and mentioned its gems, but it was only after 1891, when M.A. Grandidier gave the Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris some specimens of rubellite, sapphire and zircon, that the potential was recognized (Mineral Industry, 1921).

Lacroix (1922) provided the most detailed early account of the minerals of the island, including corundum, but gem ruby and sapphire were entirely absent. Some of the localities mentioned by 20th century writers included Mevatanana, Ambositra and Betafo, with mostly dark blue, but also colorless, red and green. Black corundum pyramids have been found associated with basaltic tuffs near Diégo-Suarez. At Betsiriry, bluish to grayish corundum is found associated with muscovite (Barlow, 1915).

Lacroix visited one alluvial gold locality southwest of Ambositra, in the bed of the small Ifèmpina river, where rolled corundum pebbles were found. While most were opaque, transparent colorless pieces up to 500 grams were reported. The deposits richest in ruby and sapphire were said to be north on the volcanic massif of Ankaratra, where corundum of basaltic origin has been obtained (Barlow, 1915).

A sapphire trader with his latest offerings at Manombo, near Ilakaka, Madagascar. Photo: R.W. Hughes, 2010. Click on the photo for a larger image.

A sapphire trader with his latest offerings at Manombo, near Ilakaka, Madagascar. Photo: R.W. Hughes, 2010. Click on the photo for a larger image.

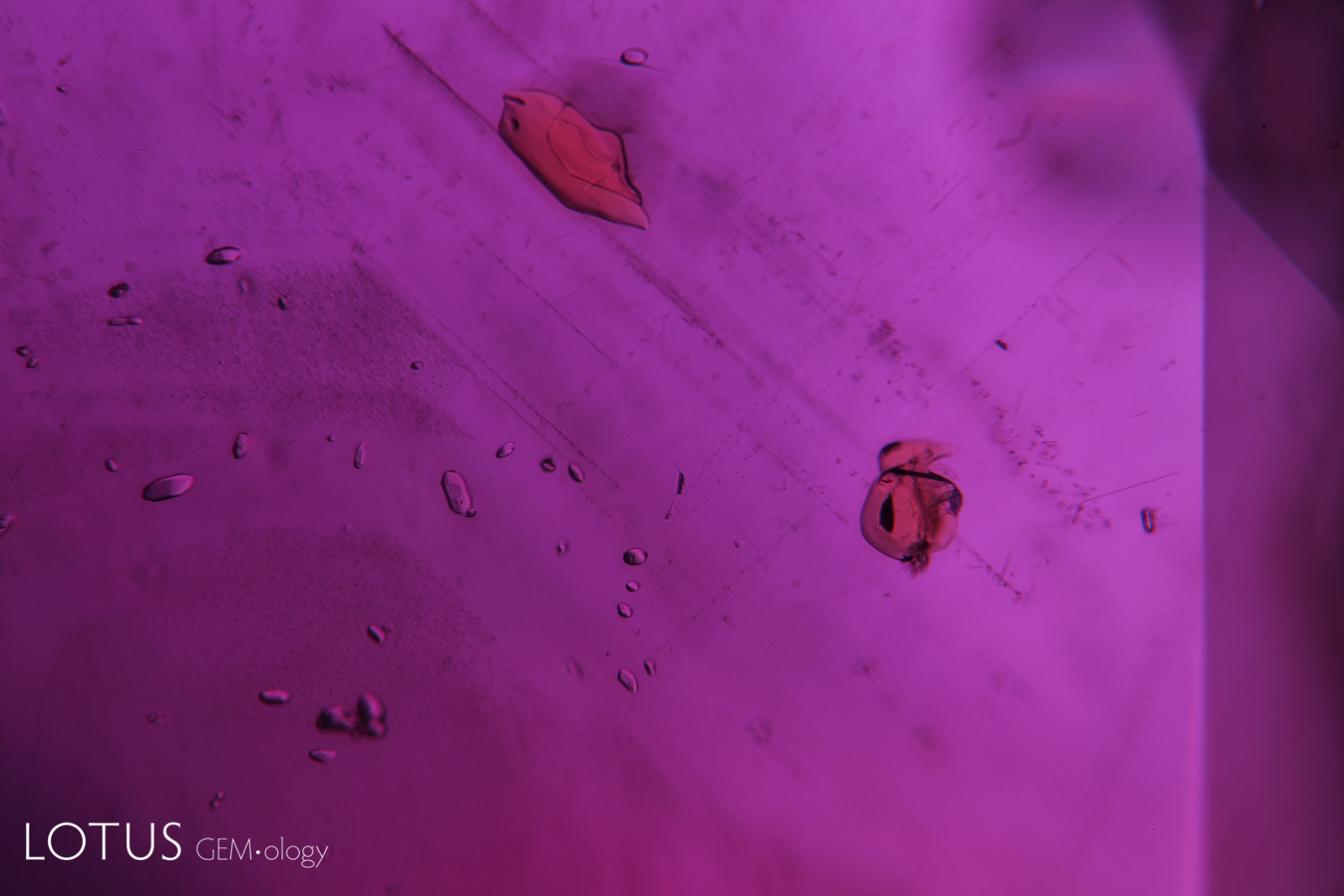

In 1990, Pierre Stéphane Salerno (pers. comm.) described to the author a sapphire occurrence southwest of Betroka, at Iankaroka (Tulear Province). These he termed polychrome sapphires, due to their unusual banding, which occurs in blue, green, brownish orange and red (including pink). Crystal habits were elongated to tabular, barrel-shaped bipyramids. The gems are said to occur along contact zones between granites and migmatites, along with iolite, green tourmaline and biotite. Inclusions of CO2 and octahedra of what is probably magnetite (the gems are attracted to a horseshoe magnet) were also reported (Koivula & Kammerling et al., 1992; John Koivula, pers. comm., March 1995).

All of this changed in 1994, when fine blue sapphires were discovered in the far south at Andranondambo. Suddenly the local population became aware of sapphire. This was closely followed by another discovery of basalt-derived blue, green and yellow sapphires in the far north at Ankarana (Ambondromifehy) in 1996. But the real boom came at Ilakaka, in 1999, and then fine ruby was found at Vatomandry a year later. Suddenly Madagascar was not just on the ruby and sapphire map, but the center of the corundum universe.

Since then, a glittering array of other occurrences of ruby and sapphire have been discovered. Incredibly, according to one study done by USAID, just ten percent of Madagascar is not gem bearing. Thus the future for Madagascar looks bright, indeed.

Is origin important? Yes, the rough sapphires do hail from India’s famous Kashmir mines. But the 14 ct cut stone is from Madagascar. What do you want? A poor quality sapphire from Kashmir or a magnificent blue beauty from Madagascar? As a friend of mine said long ago, only inclusion collectors should buy based on origin. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul. Click on the photo for a larger image.

Is origin important? Yes, the rough sapphires do hail from India’s famous Kashmir mines. But the 14 ct cut stone is from Madagascar. What do you want? A poor quality sapphire from Kashmir or a magnificent blue beauty from Madagascar? As a friend of mine said long ago, only inclusion collectors should buy based on origin. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul. Click on the photo for a larger image.

Andranondambo

In 1994, an important sapphire occurrence in Madagascar became known. This material, which has cut stones up to 20 ct, ranges from pale to rich blue and is suitable for heat treatment. Some pieces are colorless with blue cores; many are strongly zoned. The deposit, in which sapphires are found in altered marble and limestone silicates (‘skarn’), is at Andranondambo (100 km NW of Fort Dauphin, aka Taolagnaro and 25 km NE of Tranomaro) in the southwestern part of the island. The scattered occurrence lies in flat savanna terrain, with most stones collected by rural people from the surface, or from thick layers of decomposed rock (Henry Hänni, pers. comm., 10 Oct. 1994). Crystals are said to be of similar morphology to those from Kashmir (Eliezri & Kremkow, 1994).

Fine blue sapphire crystals from Andranondambo in Madagascar’s deep south. When these gems first hit the international market in the mid-1990s, they were often confused with fine sapphires from Kashmir, Sri Lanka and Myanmar. And they still are… Photo: R.W. Hughes, 2010. Click on the photo for a larger image.

Fine blue sapphire crystals from Andranondambo in Madagascar’s deep south. When these gems first hit the international market in the mid-1990s, they were often confused with fine sapphires from Kashmir, Sri Lanka and Myanmar. And they still are… Photo: R.W. Hughes, 2010. Click on the photo for a larger image.

French geologist Paul Hibon first reported sapphire at Andranondambo in the early 1950s, but the modern rediscovery of these gems dates from about 1991. According to one story we heard, a Chinese resident of Antsirabe was offered some blue stones by some Malagasy miners. He thought they might be of value and so sent them to a friend in Thailand, where they were recognized as sapphires. This set off an island-wide gem rush that has continued to the present day.

To date, the Andranondambo area remains the gold standard for Madagascar blue sapphire, with the finest stones said to come from Tiramene, just north of Andranondambo. Andranondambo sapphires can sometimes be of spectacular quality, in many respects resembling stones from the famous Kashmir, Myanmar and Sri Lankan mines. Terrific faceted stones of over 20 carats are known.

In 2005, an Australian company (S.I.A.M.) began working the Andranondambo deposit, but by the time of the author’s visit in August 2010, the company had departed, leaving only scattered groups of locals mining by hand.

Beginning in 2016, large finds of sapphire were made in the Andranondambo area, at Ankazoabo.

Washing sapphire-bearing ground at Tiramine, near Andranondambo. Photo: E. Billie Hughes, 2010. Click on the photo for a larger image.

Washing sapphire-bearing ground at Tiramine, near Andranondambo. Photo: E. Billie Hughes, 2010. Click on the photo for a larger image.

Ilakaka

Prior to the discovery of sapphire in October 1998, Ilakaka was just a wide spot in the road. Today it is the center of Madagascar’s sapphire universe. Access is via a “good” road (mostly tarmac) two days’ drive south of the capital. Because this area borders and stretches into Isalo National Park, environmental concerns have complicated the mining situation.

Ilakaka, Madagascar When sapphire was found here in 1999, a small village grew overnight into a boomtown. Even today, Ilakaka has the biggest gem market in Madagascar. Photo: R.W. Hughes, 2010. Click on the photo for a larger image.

Ilakaka, Madagascar When sapphire was found here in 1999, a small village grew overnight into a boomtown. Even today, Ilakaka has the biggest gem market in Madagascar. Photo: R.W. Hughes, 2010. Click on the photo for a larger image.

The Ilakaka mining area is huge, encompassing perhaps 4000 km2or more. This includes Ilakaka, Sakaraha, Manambo, Voavoa, Fotiyola, Andranolava and Murarano. Most (but not all) mining has taken place south of the Ilakaka–Sakaraha highway, but we witnessed mining all along a belt stretching from Ilakaka to Sakaraha. Large quantities of pink sapphire are produced, as well as blue, violet, orange (including padparadscha), yellow, green, colorless and other fancy colors. While Ilakaka is famous for the prodigious production of pink sapphires, some extremely fine blue sapphires are also found. Geuda-type sapphire from this region responds well to heat treatment.

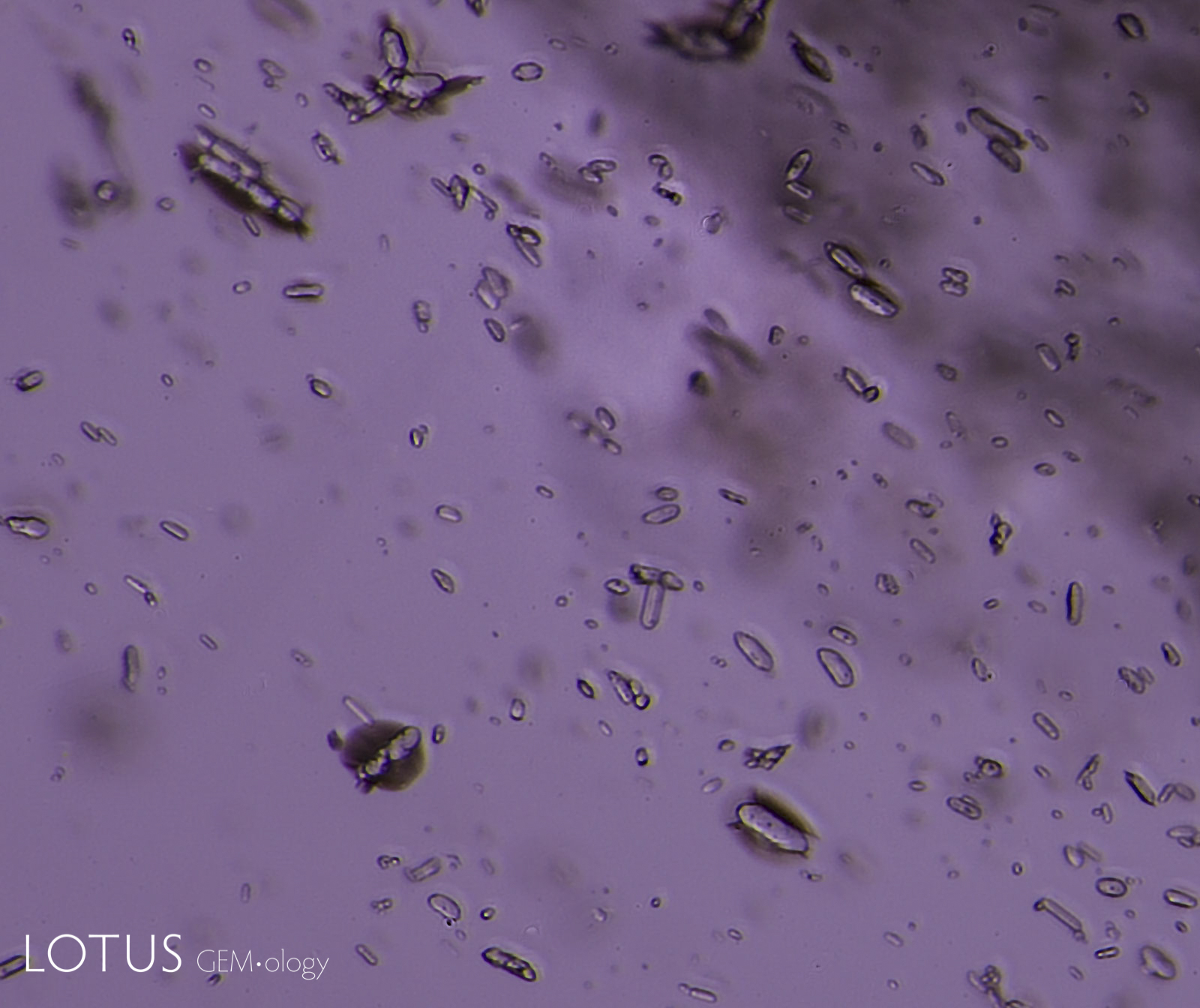

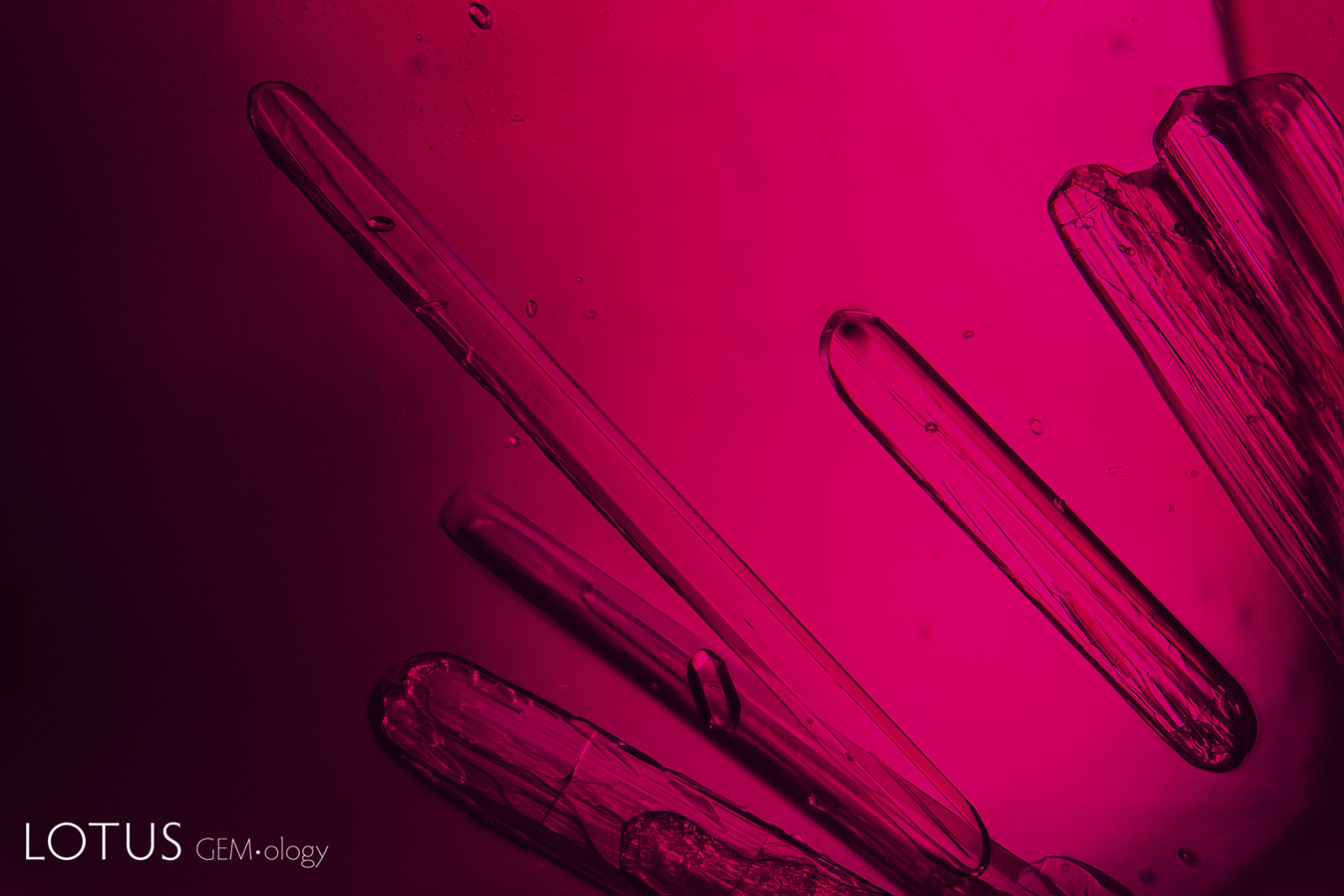

With the exception of blue stones, most Ilakaka sapphires are distinguished by large numbers of small rounded zircon inclusions, which occur singly or as clusters. Rough material is waterworn, showing little trace of the original crystal shape. Most stones tend to be less than one carat after cutting, but bigger stones are occasionally found. Cut gems above five carats are rare. To date, the largest fine faceted sapphire from this region seen by the author was 60 ct.

Malagasy miners offering their stones to Sri Lankan buyers at Manambo, just south of Ilakaka, Madagascar. Photo: R.W. Hughes, 2016. Click on the photo for a larger image.

Malagasy miners offering their stones to Sri Lankan buyers at Manambo, just south of Ilakaka, Madagascar. Photo: R.W. Hughes, 2016. Click on the photo for a larger image.

Andilamena region

The small town of Andilamena lies roughly one day’s drive north of the capital. The author visited the area in 2005 with Vincent Pardieu and Dana Schorr and the following account is from that time.

Ruby and sapphire from this region has been known since the 1990s, but it was not until about 2004 that it was extensively mined. The main mining village of Moramanga is located a long day’s walk northeast from the town of Andilamena. Demand in Thailand for low-grade ruby that can be improved by filling fractures with high-RI glass drove activity at this mine. A second mining area, Andrebabe, is noted for fine sapphire.

Special permission had to be obtained to visit the mines surrounding this town. This took a full day of cajoling. To protect us, two policemen were sent along as a guard detail. Robberies are not unknown. Just days before we had arrived a West African buyer had been knifed to death in Andilamena. Also, shortly before Vincent Pardieu’s June 2005 visit to Moramanga, a party of traders was ambushed along the trail. For that reason, Thai and Sri Lankan dealers do not visit the mines themselves, but do their buying in the town.

The author above Moramanga, Madagascar in 2005. The area at the time was producing large quantities of ruby used for glass filling, as well as polychrome sapphire. Photo: Dana Schorr. Click on the photo for a larger image.

The author above Moramanga, Madagascar in 2005. The area at the time was producing large quantities of ruby used for glass filling, as well as polychrome sapphire. Photo: Dana Schorr. Click on the photo for a larger image.

Andrebabe

A day’s walk south of Andilamena is a small jungle encampment at Andrebabe where fine-quality blue sapphires are found. The area had intrigued me ever since Vincent Pardieu mentioned it following his visit to Andilamena in June 2005. Andrebabe, it seemed, was the sapphire mine at the center of the Island at the end of the universe. The area was reported to be populated by pygmies, people said to be descended from the country’s earliest inhabitants. It was also said that they were sorcerers, people with the ability to appear and disappear at will. If we were to visit the area, we were warned we must pay strict attention to fady.

Among the more curious customs of Madagascar is that of fady. Loosely translated as “taboo,” it governs to a certain extent the behavior of people with respect to actions one takes, the food one eats and even the days of the week it is “dangerous” to do certain things. While certain fady beliefs are destructive (in the past, twins were sometimes killed or abandoned), others are beneficial. For example, the killing of certain animals is often prohibited, thus aiding conservation efforts. Similarly, the area surrounding tombs is supposed to be left undisturbed, protecting at least some of the rapidly shrinking forests.

Fady is further complicated by variations from one region to the next, one family to another, and even on an individual basis. This makes travel for the outsider somewhat problematic, as one is not always aware of just what one is, or is not, supposed to be doing.

Unheated Madagascar sapphires from the Ilakaka region, ranging from 1.3–3.9 ct. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul; specimens: cut stones from Gem Fever; rough from the Lotus Gemology collection. Click on the photo for a larger image.

Unheated Madagascar sapphires from the Ilakaka region, ranging from 1.3–3.9 ct. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul; specimens: cut stones from Gem Fever; rough from the Lotus Gemology collection. Click on the photo for a larger image.

Prior to our visit to Andrebabe, we were given strict instructions that all fady must be followed. Now if we could just figure out what they were! The fady were said to include no wearing of red, no killing of animals, and no work on certain days of the week. Simple, I thought to myself, I’ll just pretend to be a Hindu Catholic.

We were warned that failure to obey the fady could have dire consequences. Witness the miner at Andrebabe who disobeyed the fady about working on certain days of the week. One day his gem pit filled with water and, as he descended to bail it out, a large eel that had appeared out of nowhere, literally hundreds of miles from the nearest ocean, attacked him. Ouch! No working on Tuesdays for me. I hate Tuesdays!

Vincent had actually planned to make the trek to Andrebabe on his previous visit, but was so exhausted upon his return from Moramanga and its rats that he didn’t have the stomach for it. And so, four months later, as we huddled over the map in Andilamena, we batted the idea back and forth. Should we, could we? Finally, a consensus was reached. We’d give it our best shot.

The following morning we assembled for what our guide Gaeton had suggested would be a 15-minute ride to the trailhead. Some ninety minutes later we rolled out of our 4x4 after our driver refused to go further up a track that resembled nothing so much as some devil’s roller coaster. Mother Nature protects her treasures well.

The trace contoured up and down a series of ridges as we walked into the mist, all to the accompaniment of ghostly howls from the nearby rainforest. Were these lemurs, or perhaps the sorcerers’ siren songs? I wasn’t about to find out.

After several hours, we came to a house, and a few hundred meters below it, a truck stuck in the mud. The drivers were attempting to winch it up the hill and, at the rate of progress they were making, they just might have it to the top by Christmas.

Continuing down, we spied Andrebabe peak. A steep downhill stretch brought us to a clearing. As we entered, shifting shadows quickly disappeared into the surrounding forest. Someone had left in a hurry. We had arrived at Andrebabe.

Time was short if we were to avoid spending a night in the forest. We quickly took lunch and then set about exploring the area. Fresh diggings were located; Vincent and Dana even managed to locate a friendly boa constrictor. All too soon, it was time to go.

Buying in Ilakaka—Not for the inexperienced Above left: The action at Marc Noverraz’s Colorline buying office in Ilakaka can get quite intense at times. Photo: R.W. Hughes, 2016. Click on the photo for a larger image.

Buying in Ilakaka—Not for the inexperienced Above left: The action at Marc Noverraz’s Colorline buying office in Ilakaka can get quite intense at times. Photo: R.W. Hughes, 2016. Click on the photo for a larger image.

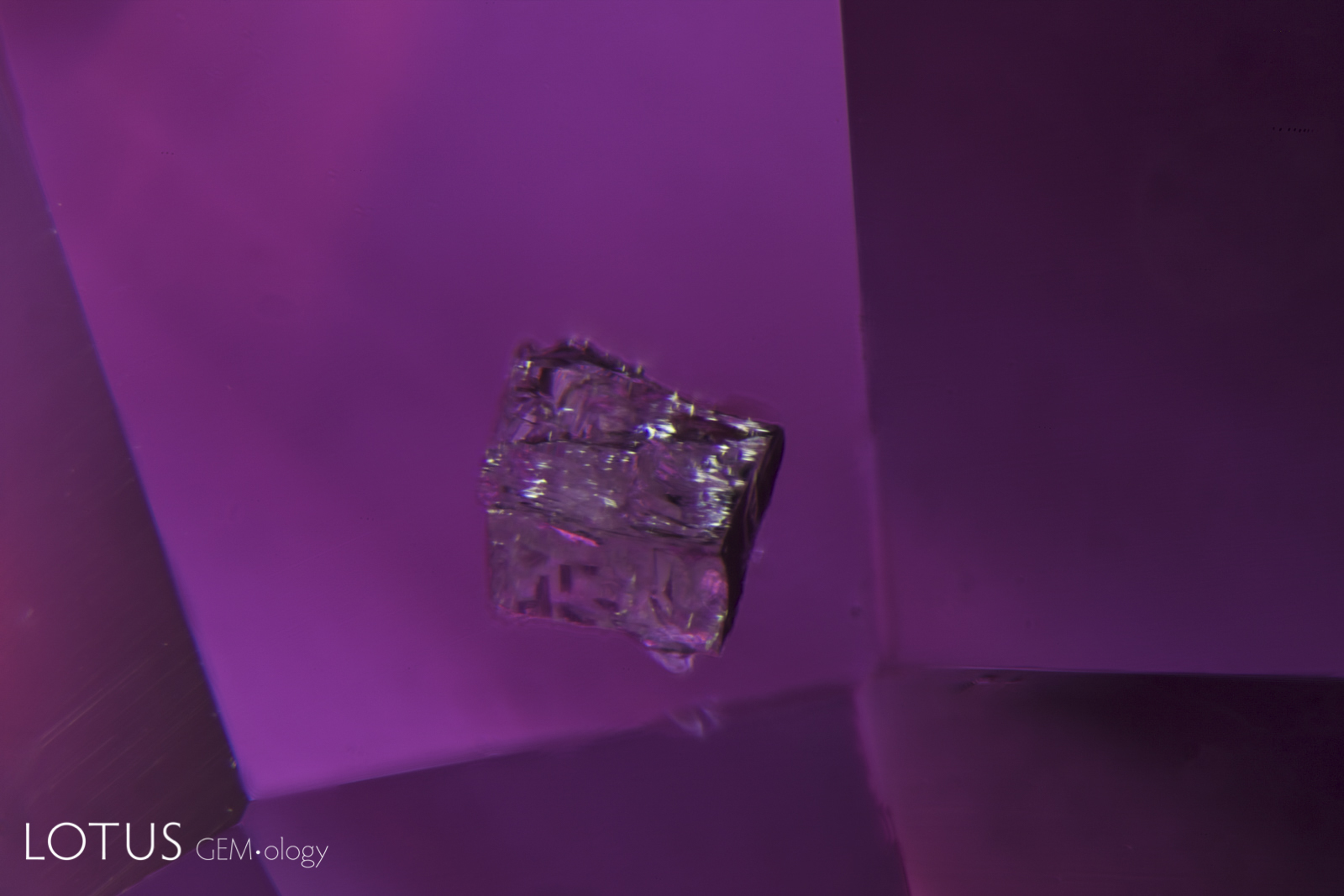

Rough gem samples purchased at Colorline’s Ilakaka office (clockwise from top left): Verneuil synthetic corundum, blue glass, zircon and spinel, coated natural sapphire; natural untreated blue and yellow sapphire. Note that these were purchased just to get a snapshot of what was in the market, even though we knew many were not what they were represented as by the sellers. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul. Click on the photo for a larger image.

Rough gem samples purchased at Colorline’s Ilakaka office (clockwise from top left): Verneuil synthetic corundum, blue glass, zircon and spinel, coated natural sapphire; natural untreated blue and yellow sapphire. Note that these were purchased just to get a snapshot of what was in the market, even though we knew many were not what they were represented as by the sellers. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul. Click on the photo for a larger image.

Moramanga

The way to Moramanga involved one hour by road, followed by a combination of jungle walk and boat. If one leaves Andilamena early in the morning, with luck it is possible to be in Moramanga by nightfall. Luck stayed behind, so for us it became a two-day journey, broken in a small riverside village.

We had been warned to be ready for some serious mud, but thankfully the track the first day was mostly dry. We were also warned to be prepared for some serious rats, and on this count, the journey did not disappoint.

The following day, we met the mud, fording one stream after another. Finally, crossing one rise we found ourselves descending into a cauldron of human activity where tiny huts were stacked on top of one another like a long brown snake coiling through the jungle. We had arrived at Moramanga.

The scene was one straight out of America’s gold rush, albeit in a jungle setting. Some 15,000 people had carved out a toe-hold from the surrounding forest where they mine for both ruby and sapphire. They mine the hillsides, they mine the river bottoms, they mine the mountaintops. They even mine the muddy effluent-ridden lanes of the town itself. I have seen some spectacular mining camps in my day (Myanmar’s jade mines come immediately to mind), but I don’t believe I’ve ever seen anything quite like Moramanga, where thousands of miners are living and working literally on top of one another.

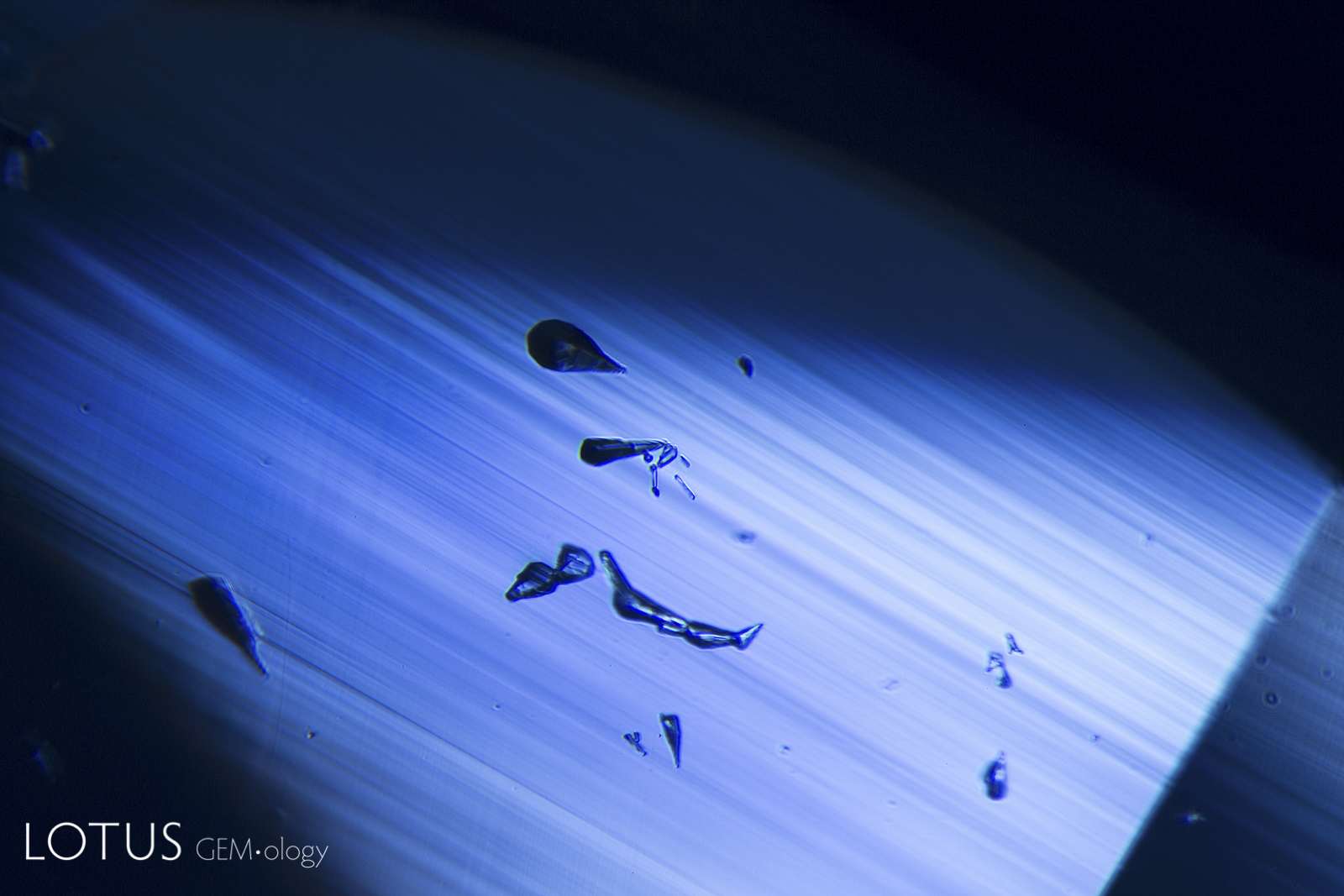

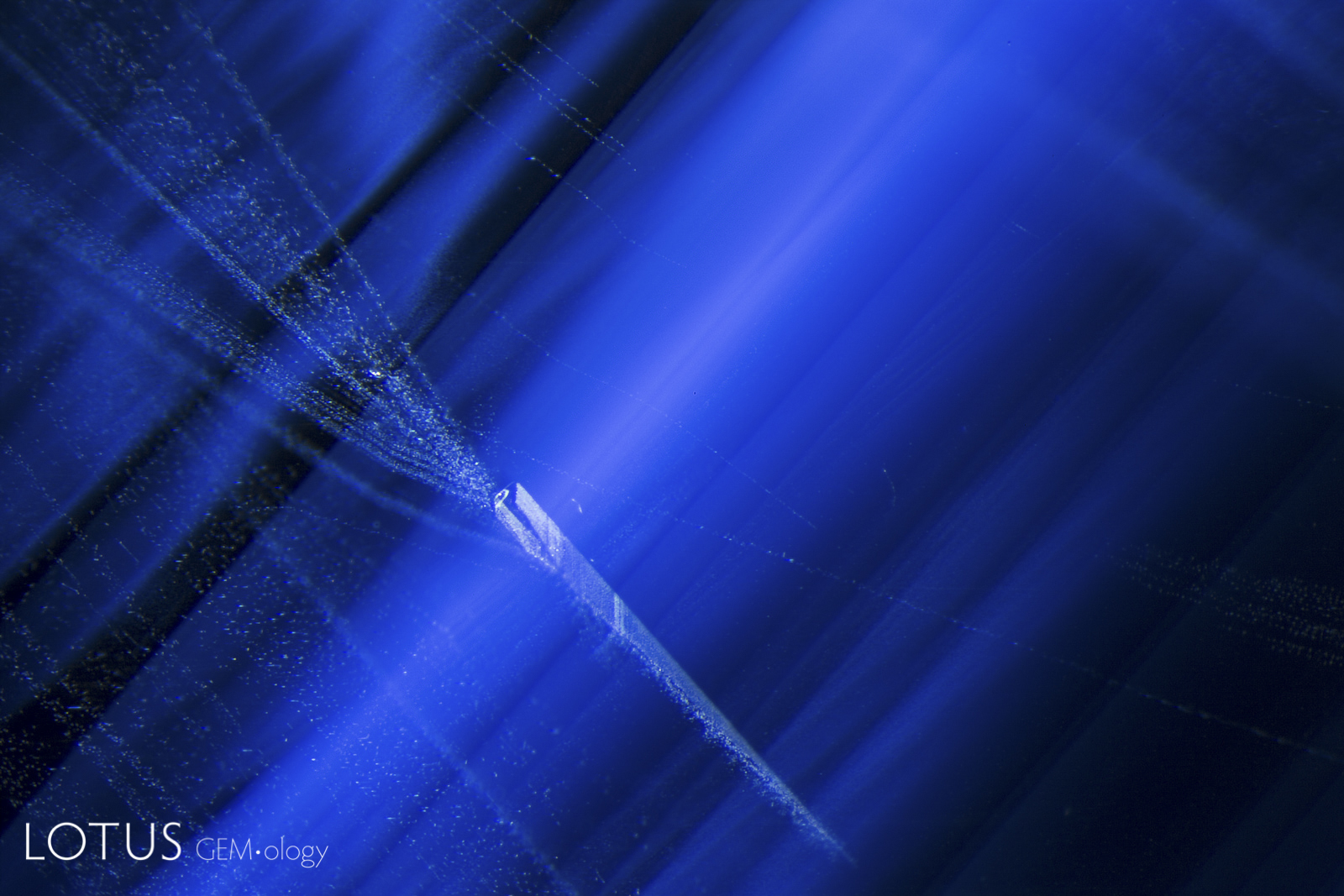

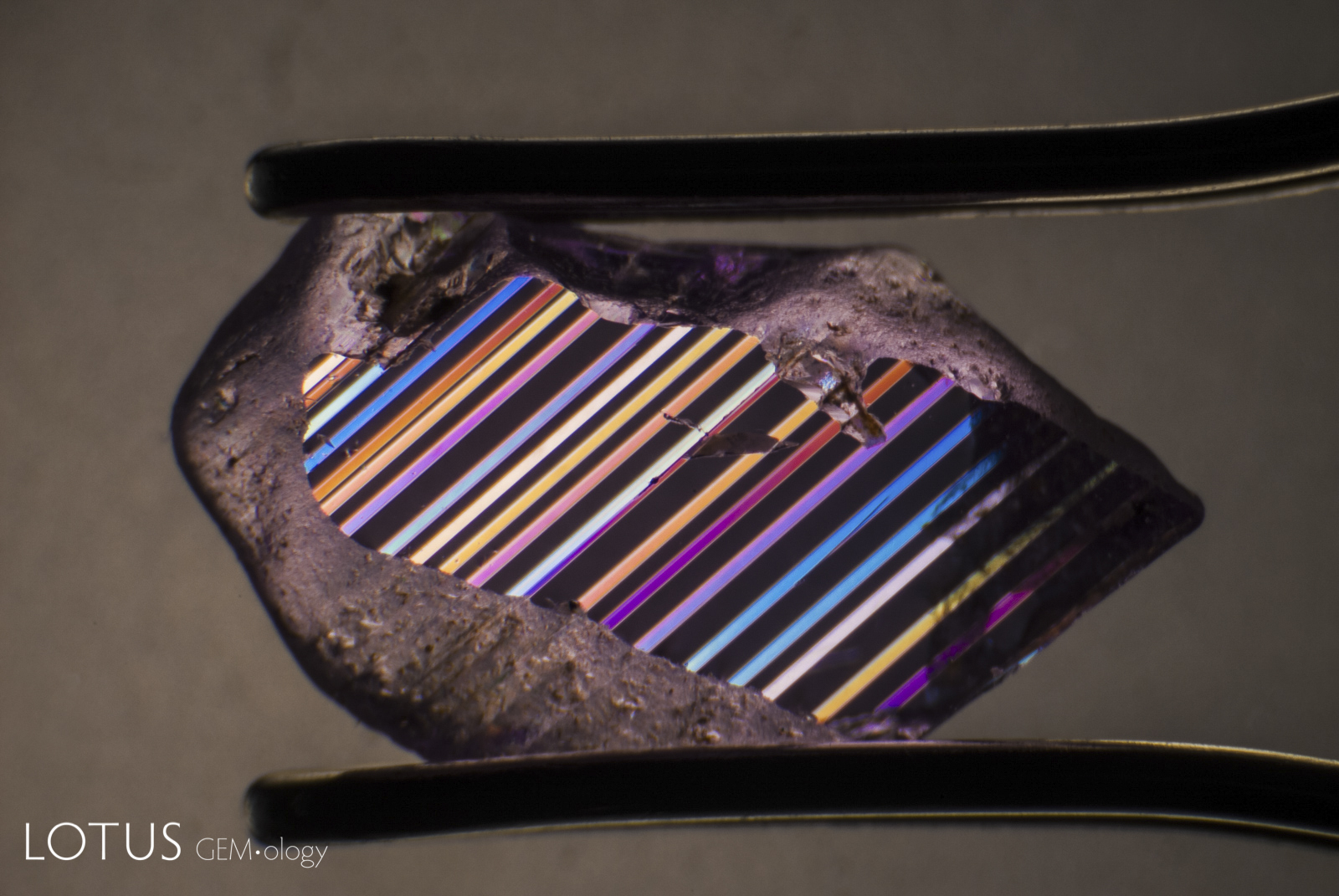

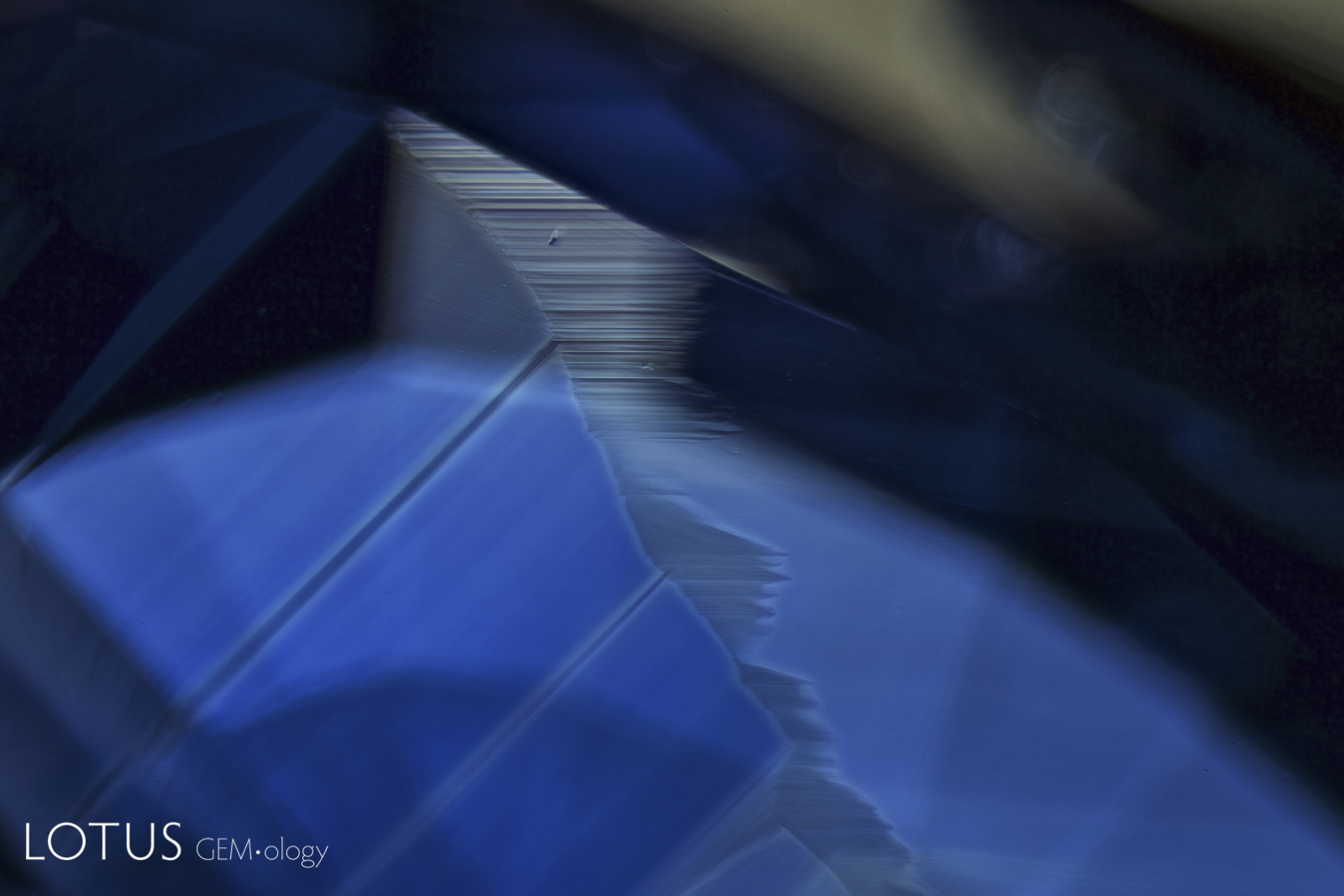

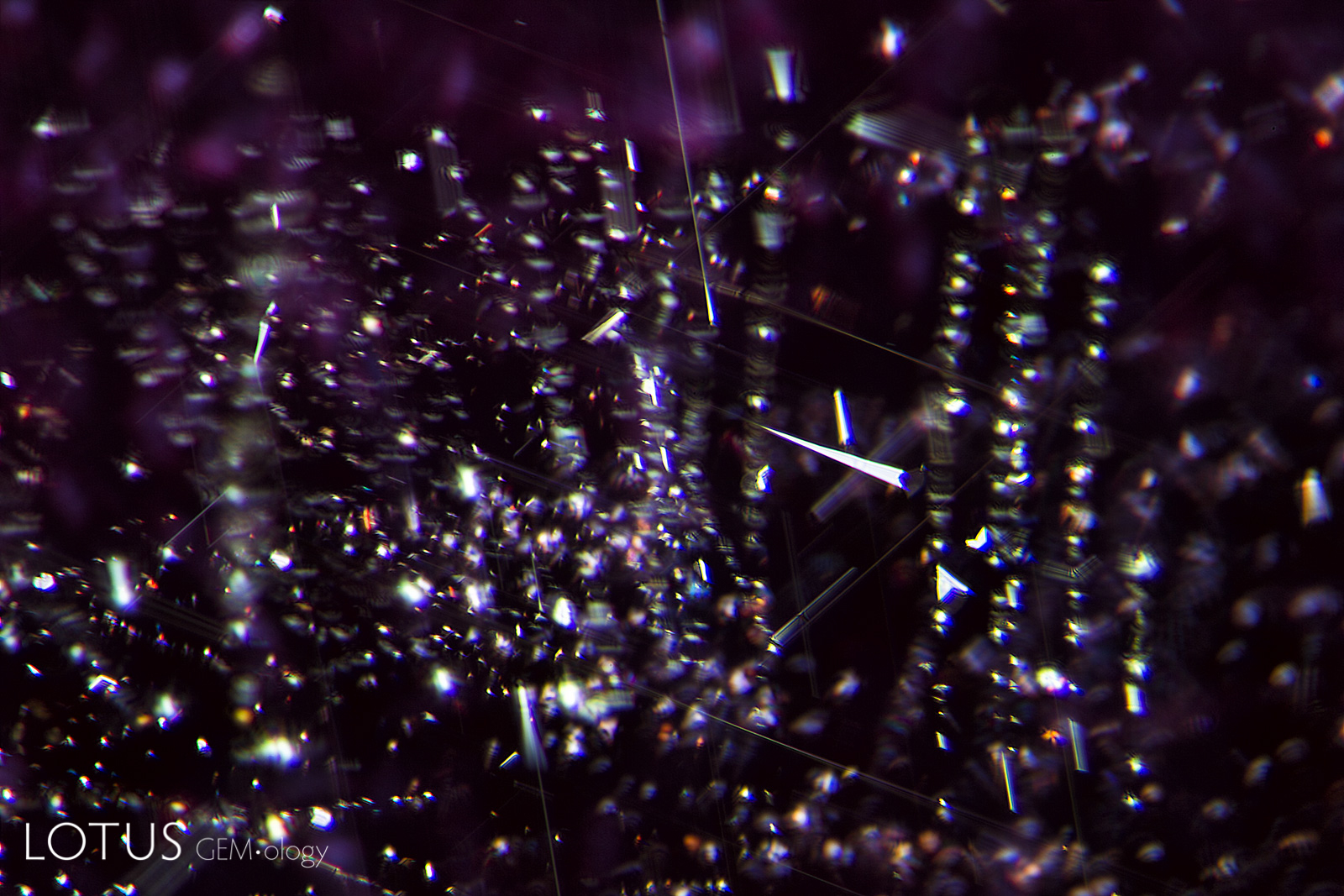

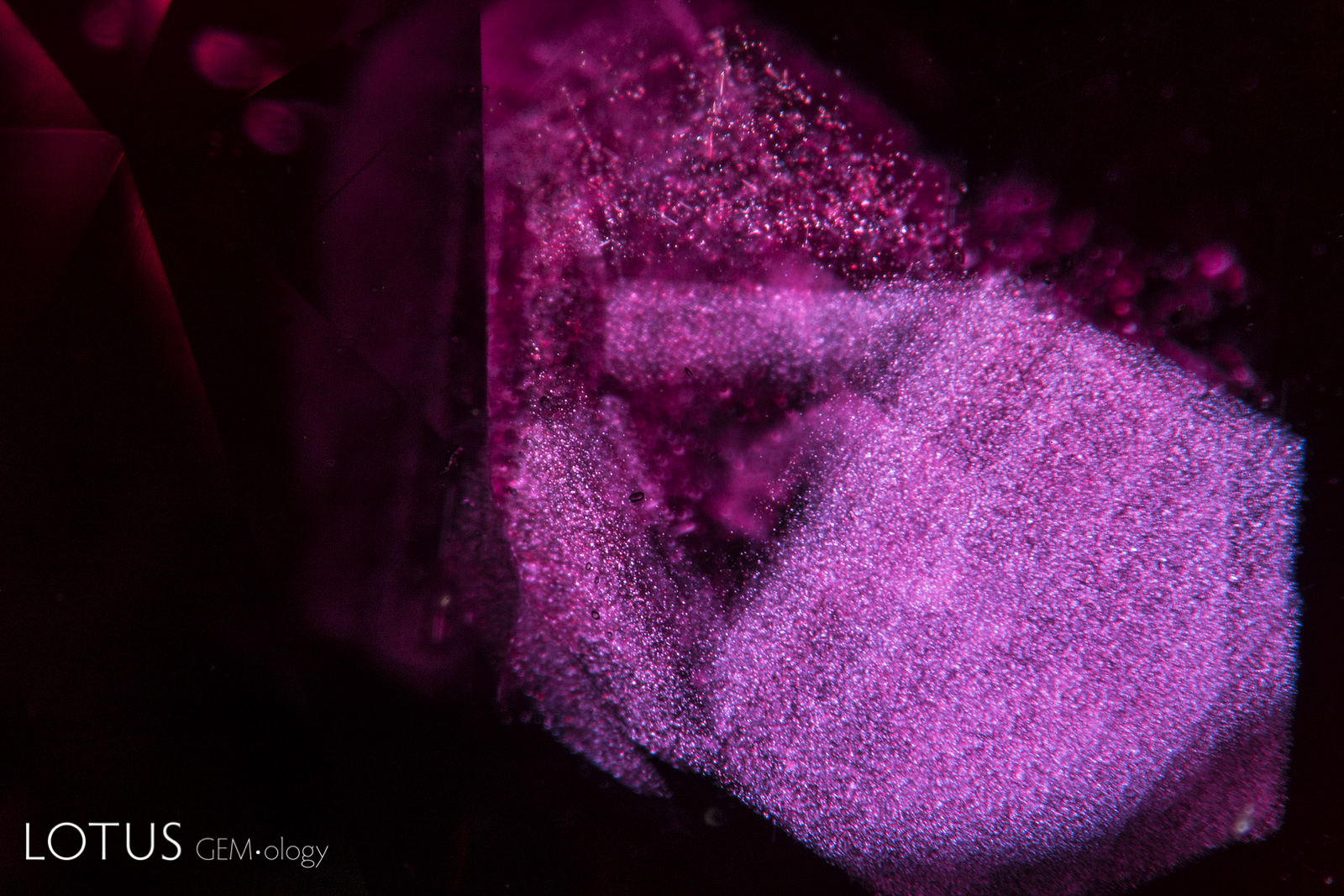

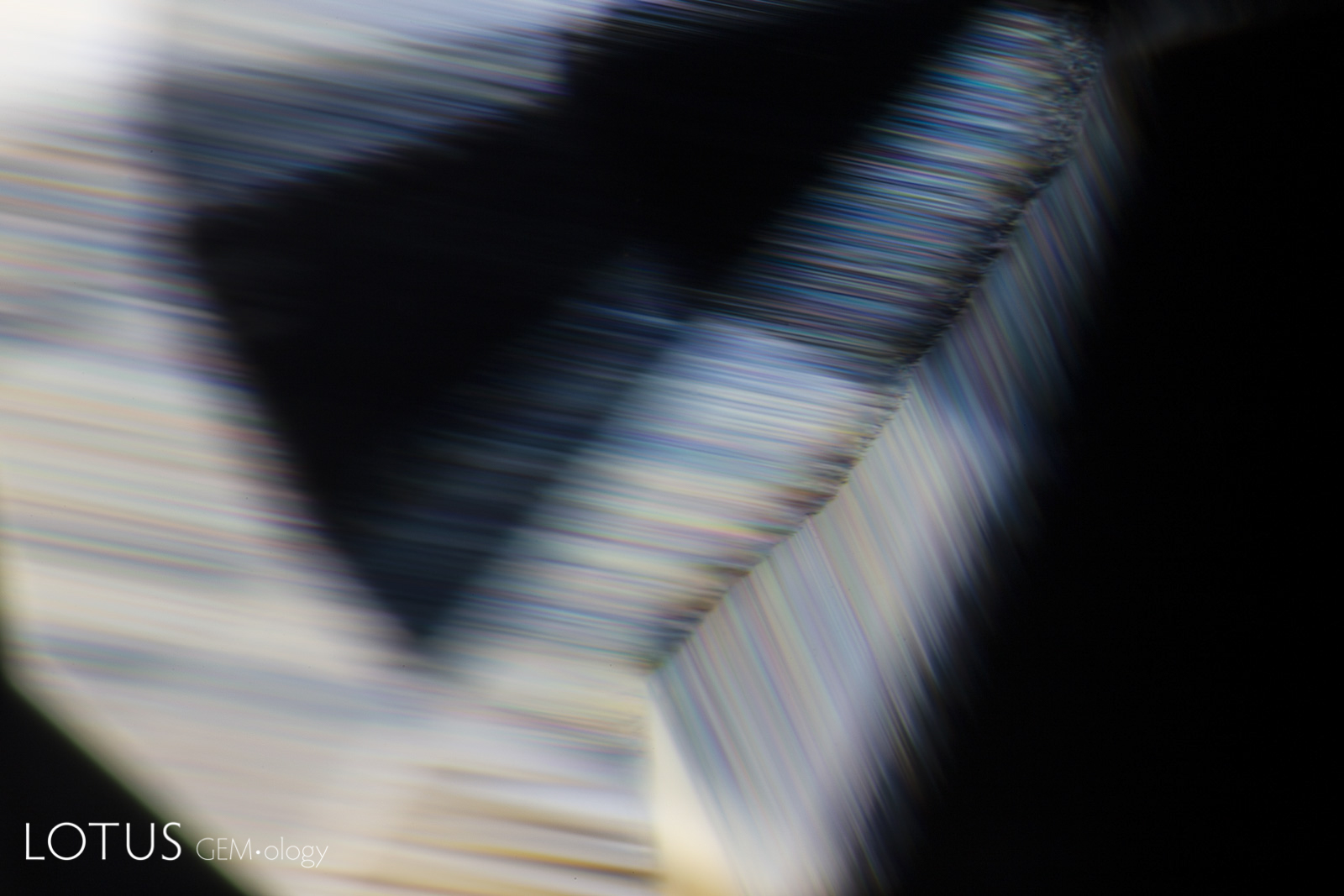

Perhaps the most diagnostic inclusion of Madagascar blue sapphire is the presence of extremely sharp growth zoning coupled with extremely fine clouds of exsolved matter. The zoning is so sharp that at times it acts as a diffraction grating, producing iridescence, such as shown here. Photo: R.W. Hughes; click on the photo for a larger image.

Perhaps the most diagnostic inclusion of Madagascar blue sapphire is the presence of extremely sharp growth zoning coupled with extremely fine clouds of exsolved matter. The zoning is so sharp that at times it acts as a diffraction grating, producing iridescence, such as shown here. Photo: R.W. Hughes; click on the photo for a larger image.

Didy

In April of 2012, Madagascar was the scene of yet another important ruby and sapphire strike. The locality was in a jungle-clad area near a village called Didy, about 150 km northeast of the capital (Pardieu & Rakotosaona, 2012; Peretti & Hahn, 2012, 2013). Within weeks Ilakaka was depopulated as both miners and traders rushed north to the new site. Both ruby and blue sapphire were found, including some of the best stones ever recovered from Madagascar.

Didy ruby frequently has a slightly orangy tint, somewhat like stones from Winza (Tanzania), but with virtually no brown. One five-carat Didy ruby seen by the author was a world-class stone, holding its intense crimson color in any and all lights. And Didy sapphire is equally spectacular, a rich royal blue that has resulted in cut stones of 50 ct or more.

Ambodivoahangy (Zahamena National Park)

Once again Madagascar shook the gem world with a discovery of ruby at Ambodivoahangy, in Zahamena National Park in July 2015. These rubies bear a striking resemblance to those further north at Moramanga, near Andilamena. The author has examined many fine gems in the one to six carat range, including some of the coveted pigeon’s blood red color (Hughes & Manorotkul et al., 2015).

Vatomandry

Some of Madagascar’s finest rubies occur near the town of Vatomandry, east of the capital of Antananarivo. The mining areas are at Tetezampaho, Ambidotavolo and Ambodivandrika.

While Hunstiger (1989–90) reported ruby at Vatomandry, in September 2000 fine stones were found and soon a rush of miners descended upon the area. In February 2001, the Madagascar government closed the area. By June 2005, most miners had left for the Andilamena area.

Ambohimandroso

This deposit, which produces pinkish ruby and pink sapphire, was discovered in late 2004. The main mining area is located at Antsahanandriana, to the east of the road between the capital at Antananarivo and Antsirabe. By January 2005, over 2000 miners swamped the deposit. Like many mining areas in Madagascar, disputes over mining rights have created turmoil and uncertainty. At the time of Vincent Pardieu’s visit in June 2005, the deposit was under military lock-and-key.

The far north

Sapphire occurs in northern Madagascar near both Diego Suarez (a.k.a. Antsiranana) (at Ambondromifehy) and Nosy Be. In both locales, the corundum is derived from basaltic source rocks, and so tends to occur in green, yellow and inky blue colors.

In 1995, woodcutters in the Ankarana forest near Ambondromifehy came across fistfuls of blue stones. At first thought to be useless, when they were later identified as sapphire, the rush was on. This deposit has been a major producer of commercial grade sapphire.

Properties of Madagascar (Andranondambo) sapphirea | |

|---|---|

| Property | Description |

| Color range/phenomena | Zoned colorless to deep blue; star stones are not found |

| Geologic formation | Metamorphic skarn-type deposits |

| Crystal habit | Typically single pyramids; also tabular hexagonal prisms and occasionally bipyramids |

| Spectra | Typical low Fe spectrum |

| Fluorescence | LW: Generally inert; Cr-bearing stones may fluoresce weak red SW: Generally inert; the clay coating on crystals may fluoresce chalky in SW, but once polished, this is gone. Heat-treated specimens often fluoresce chalky blue-green in SW |

| Inclusion types | Description |

| Solids |

|

| Cavities (liquids/gases/solids) |

|

| Growth zoning | Extremely sharp growth zoning, particularly parallel to the basal plane; crystals show blue cores and colorless skins or the reverse |

| Twin development | Small growth twins have been seen, but are rare; polysynthetic twinning has not been reported |

| Exsolved solids | Rutile and Fe-rich silk have been seen in a small number of specimens |

| a. This table is based on the author’s own research, along with the published reports of Milisenda & Henn (1996), Kiefert & Schmetzer et al. (1996), Schwarz & Petsch et al. (1996) and Gübelin & Koivula (2008). | |

Inclusions of central Madagascar ruby (Andilamena region) | |

|---|---|

|

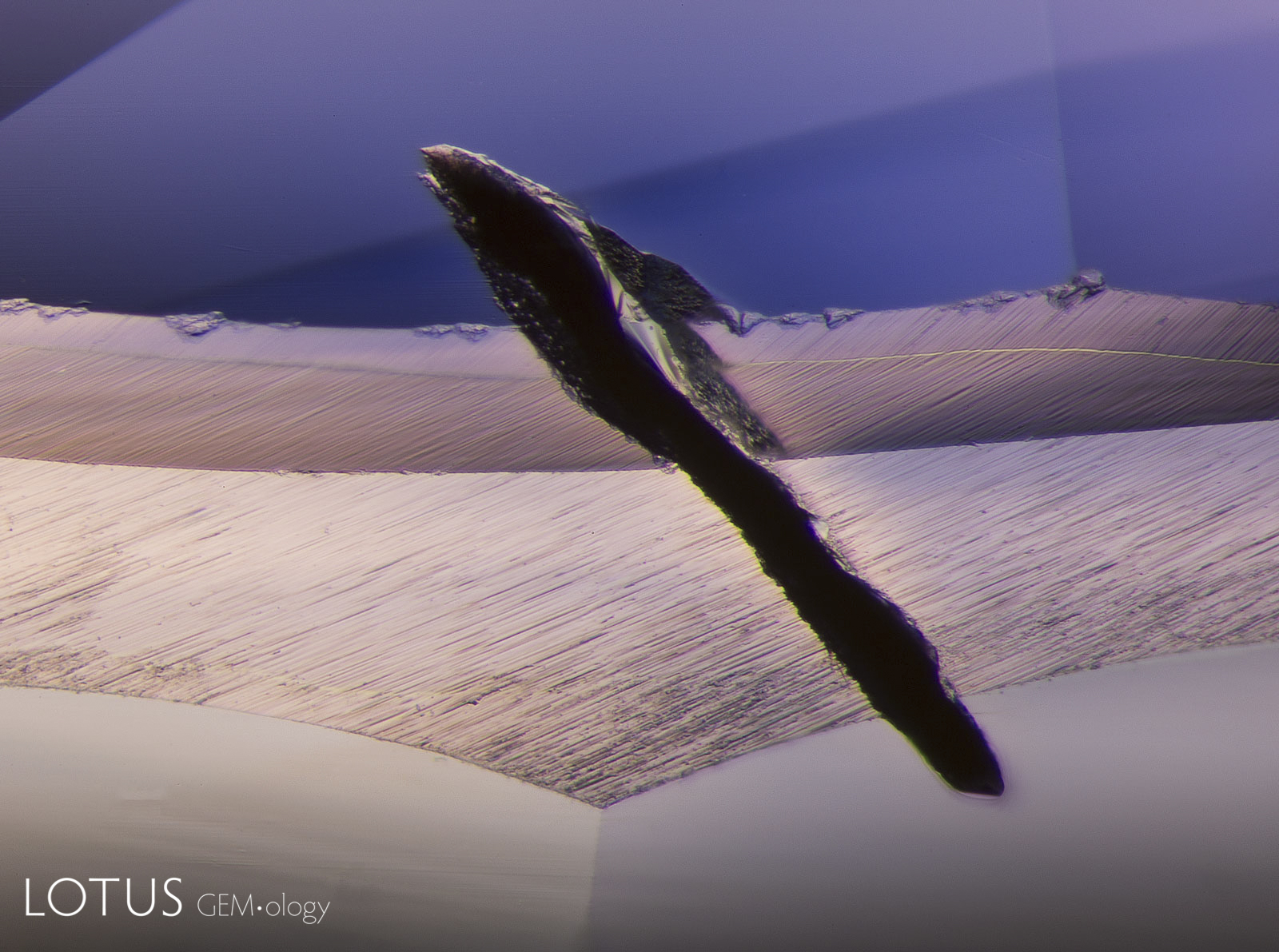

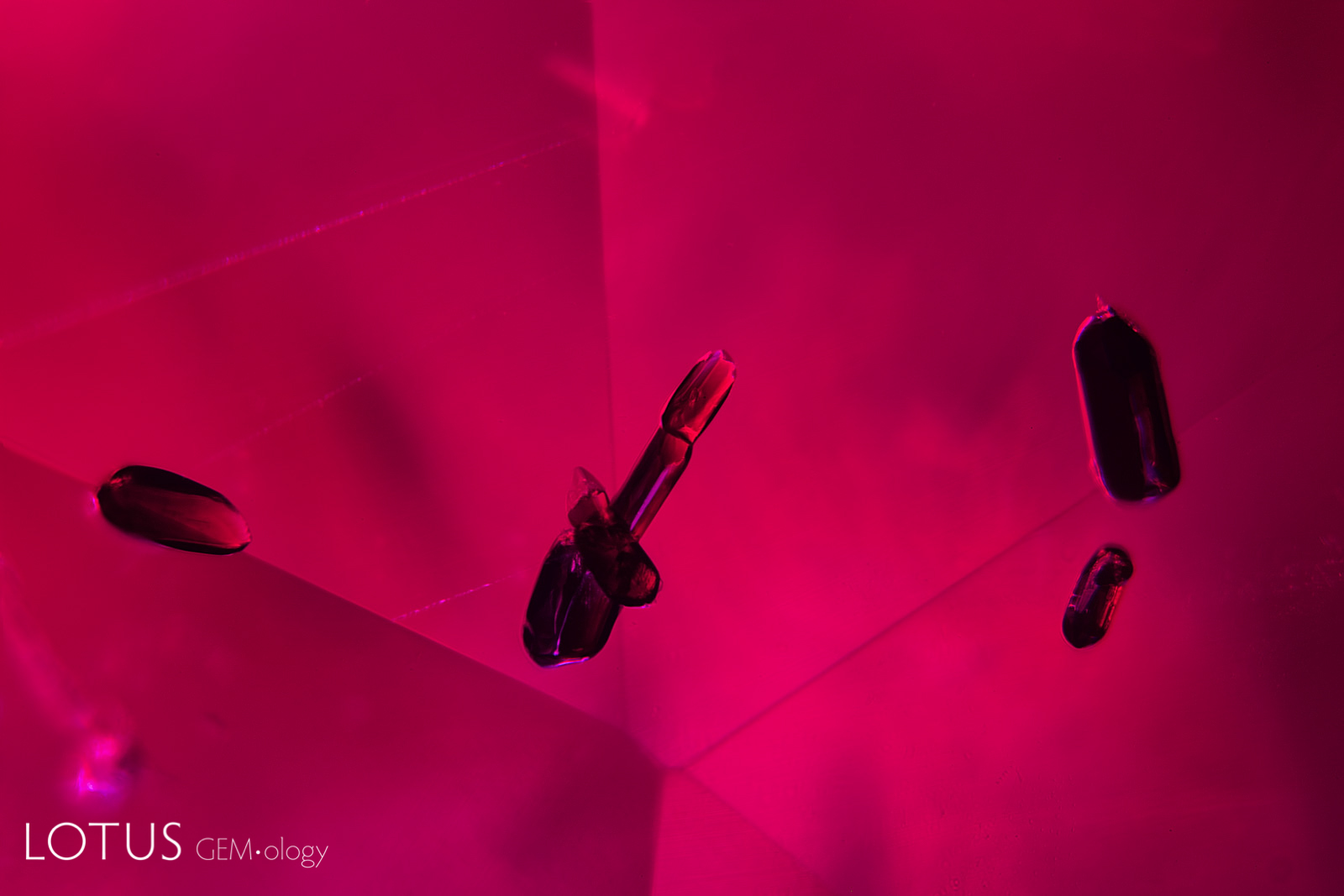

Primary rutile rods surround a hexagonal cloud of exsolved rutile silk and particles. Photo: Richard W. Hughes; click on the photo for a larger image. |

Primary rutile rods are one of the most distinctive inclusions found in rubies from Andilamena, Madagascar. Photo: Richard W. Hughes; click on the photo for a larger image. |

|

Secondary exsolved rutile silk in a ruby from Andilamena, Madagascar. Photo: Richard W. Hughes; click on the photo for a larger image. |

Secondary exsolved rutile silk in a ruby from Andilamena. Photo: Richard W. Hughes; click on the photo for a larger image. |

|

Like their cousins from nearby Mozambique, rubies from the Andilamena region frequently feature amphibole rods. Photo: Richard W. Hughes; click on the photo for a larger image. |

Amphibole rods in Andilamena ruby. Photo: E. Billie Hughes; click on the photo for a larger image. |

|

Again, like their Mozambique cousins, Andilamena rubies may feature mica inclusions. Photo: Richard W. Hughes; click on the photo for a larger image. |

Orange monazite crystals, along with rounded zircons in Andilamena rubies. These inclusions are generally not found in rubies from Mozambique, and thus provide an excellent means of separation. Photo: Richard W. Hughes; click on the photo for a larger image. |

Properties of central Madagascar ruby (Andilamena region)a | |

|---|---|

| Property | Description |

| Color range/phenomena | Hue: red; saturation: vivid to intense; tone: deep to medium deep; most stones fall into the “Royal Red” Lotus Gemology color type; a small number fall into the Lotus “Pigeon’s Blood” color type |

| Geologic formation | Source rock is thought to be an amphibolite, similar to ruby from Mozambique |

| Crystal habit | Hexagonal prism/pinacoid combinations, with small development of the rhombohedron faces |

| Spectra | Strong Cr spectrum with moderate to low violet transmission |

| Fluorescence | LW (366 nm): Medium to strong red SW (254 nm): Very weak to weak red |

| Inclusion types |

|

| Solids | Description |

| Cavities (liquids/gases/solids) |

|

| Growth zoning | Sharp angular growth zoning |

| Twin development | Polysynthetic twinning on the rhombohedron |

| Exsolved solids | Hexagonal or angular zoned clouds composed of minute exsolved particles and rutile silk intersecting in three directions in the basal plane |

| a. This table is based on the author’s own research, along with the published reports of Hughes & Manorotkul et al. (2015) | |

References

- Barlow, A.E. (1915) Corundum, its occurrence, distribution, exploitation, and uses. Canada Department of Mines, Geological Survey Memoir, No. 57, 377 pp.; RWHL*.

- Eliezri, I.Z. and Kremkow, C. (1994) The 1995 ICA world gemstone mining report. ICA Gazette, December, p. 1, 9 pp.; RWHL.

- Gübelin, E.J. and Koivula, J.I. (2008) Photoatlas of Inclusions in Gemstones, Volume 3. Basel, Switzerland, Opinio Publishers, 672 pp.; RWHL*.

- Hughes, R.W., Manorotkul, W. et al. (2015) Let it bleed: New rubies from Madagascar. <https://lotusgemology.com//library/articles/322-blood-red-rubies-from-madagascar-lotus-gemology>, accessed 2 September 2015; RWHL*.

- Hunstiger, C. (1989–90) Darstellung und Vergleich primärer Rubinvorkommen in metamorphen Muttergesteinen [Presentation and comparison of primary ruby occurrences in metamorphic rock]. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Gemmologischen Gesellschaft, Part I: Petrographie und Phasenpetrologie, Vol. 38, No. 4, pp. 113–138; Part II: Petrographie und Phasenpetrologie, Vol. 39, No. 1, pp. 49–63; Part III: Petrographie und Phasenpetrologie, No. 2/3, pp. 121–145; RWHL*.

- Kiefert, L., Schmetzer, K. et al. (1996) Sapphires from Andranondambo area, Madagascar. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 25, No. 3, pp. 185–209; RWHL*.

- Koivula, J.I., Kammerling, R.C. et al. (1992a) Gem News: An unusual zoned specimen; sapphires from Madagascar. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 28, No. 3, pp. 200–201; 203–204; RWHL.

- Koivula, J.I., Kammerling, R.C. et al. (1992b) Gems News: Sapphires from Madagascar. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 28, No. 3, pp. 203–204; RWHL.

- Lacroix, A. (1912) Un voyage au pays des béryls (Madagascar). La Géographie, Vol. 26, No. 5, pp. 285–296; not seen.

- Lacroix, A. (1913) A trip to Madagascar, the country of beryls. Annual Report of the Smithsonian Institution, pp. 371–382; RWHL*.

- Lacroix, A. (1922, 1923) Minéralogie de Madagascar. Paris, Société d’Editions Géographiques, Maritimes et Coloniales, 3 vols., I, 624 pp.; II, 694 pp.; III, 450 pp.; RWHL*.

- Milisenda, C. and Henn, U. (1996) Compositional characteristics of sapphire from a new find in Madagascar. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 25, No. 3, pp. 177–184; RWHL.

- Milisenda, C., Henn, U. et al. (2001) New gemstone occurrences in the south-west of Madagascar. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 27, No. 7, pp. 385–394; RWHL*.

- Mineral Industry (1915–1921) [Madagascar corundum]. In The Mineral Industry, its Statistics, Technology and Trade During 1915… 1921, ed. by G.F. Kunz and G.A. Roush, ed., New York, McGraw-Hill, Vols. 24, 26, 29, 30, 1915: p. 600; 1917: p. 600; 1920: p. 600; 1921: p. 600; RWHL.

- Pardieu, V. and Rakotosaona, N. (2012) Ruby and Sapphire Rush Near Didy, Madagascar (April–June 2012). GIA News from Research, Bangkok, October 14, 84 pp.; RWHL*.

- Peretti, A. and Hahn, L. (2012) Record-breaking discovery of ruby and sapphire at the Didy mine in Madagascar: Investigating the source. InColor, No. 21, Fall/Winter, pp. 22–35; RWHL.

- Peretti, A. and Hahn, L. (2013) Record-breaking rubies discovered in Didy, Madagascar. Contributions to Gemology, No. 13, May, pp. 2–16; RWHL*.

- Schwarz, D., Petsch, E.J. et al. (1996) Sapphires from the Andranondambo region, Madagascar. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 32, No. 2, pp. 80–99; RWHL*.

Acknowlegements

The authors would like to thank the following individuals for their assistance: Marc Noverraz & Guillaume Soubiraa of Colorline, Nirina Rakotosaona, Tom Cushman and Vincent Pardieu.