A. A heat-altered crystal with an iridescent decrepitation halo, alongside a surface cavity filled with glass.

B. When the direction of the reflected light is changed to show the surface, it reveals patches of glass on the surface (right).

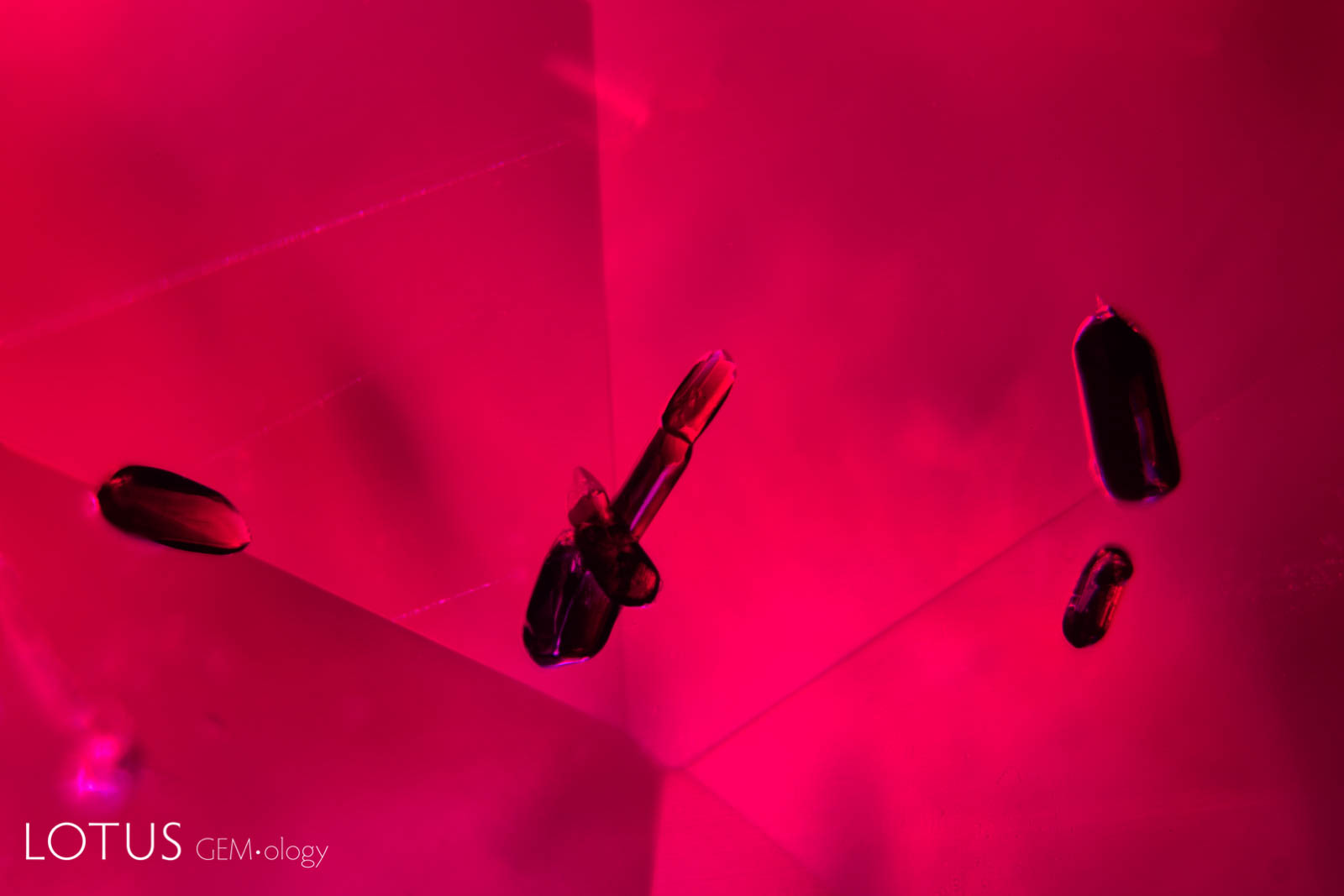

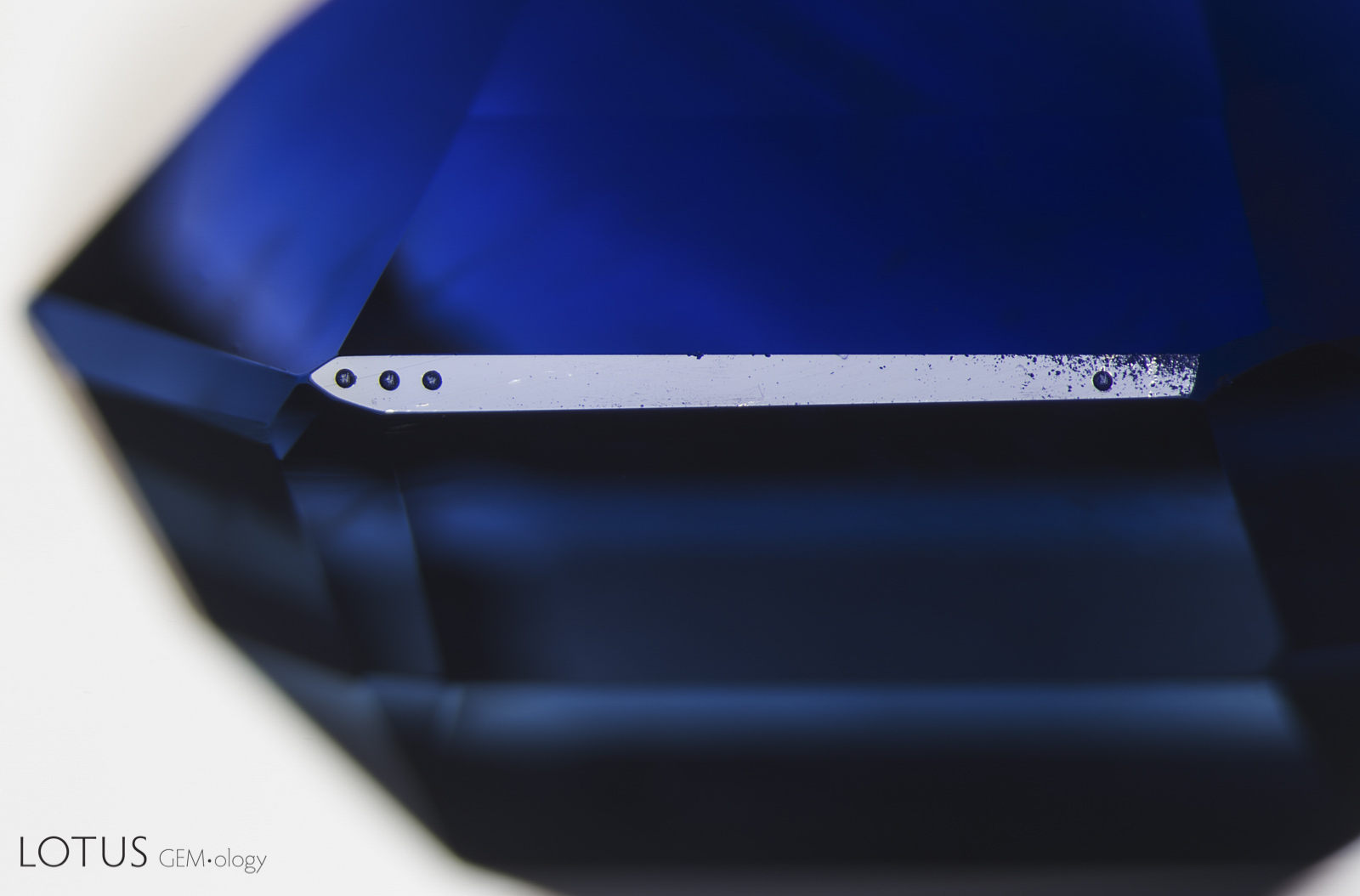

A. When a crystal is heated (either by a magma or artificially by human intervention), it expands. Tension is often relieved by a fissure in the weakest direction, which in corundum is in the basal plane. As shown above, such fissures are difficult to see in dark-field illumination. In the background one can see ink spot internal diffusion caused by high-temperature heat treatment.

B. If the lighting is changed from dark field to overhead fiber-optic, the flat tension disc appears in dramatic relief. This example is in a heat-treated blue sapphire from Bo Ploi (Kanchanaburi), Thailand. Such inclusions are quite common in both rubies and sapphires recovered from magmatic sources.

A. Kashmir sapphires are unique in that the skin of many crystals feature deep blue spots of color, like spots on a leopard’s back.

B. These blue spots are sometimes incorporated into finished stones, where they will be found just below the surface.

A. Secondary "fingerprint" in a Mong Hsu (Myanmar) ruby before heating. Note the angular nature of the negative crystal channels.

B. Following heat treatment with flux, one can see the "necking down" and rounding of the channels. For more on this, see "Fluxed Up: The Fracture Healing of Ruby."

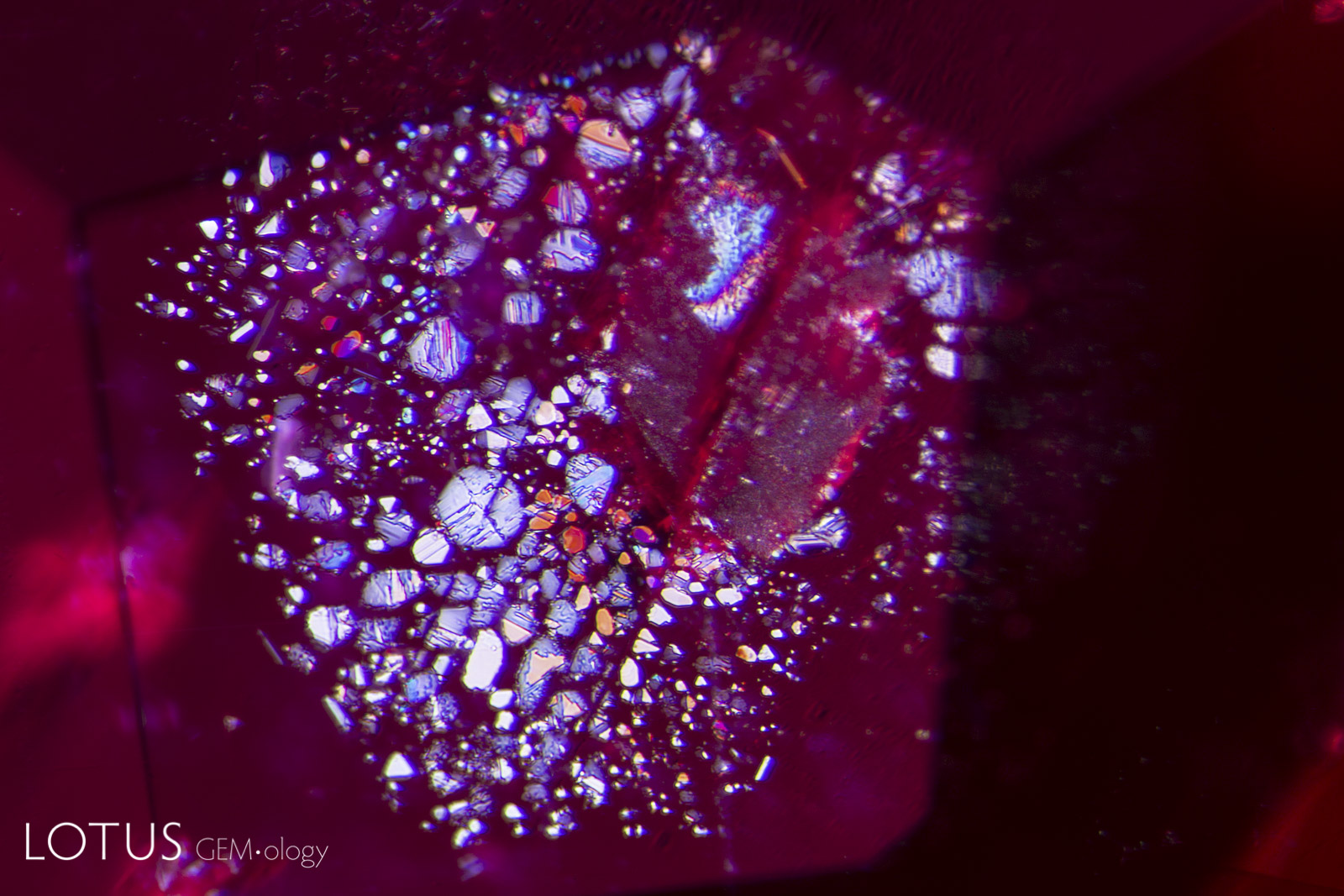

A. A lovely rosette inclusion surrounds a mica crystal in this ruby from Mozambique’s Montepuez region. This “rosette” actually consists of negative crystals flattened in the plane of basal pinacoid (perpendicular to the c axis). Oblique fiber-optic lighting.

B. When viewed with dark field and oblique fiber-optic illumination, the appearance changes dramatically, illustrating the importance of utilizing various illumination techniques with the microscope.

A. Mozambique silk before heating shows a high luster rutile needle and an attached lower luster daughter crystal.

B. When such a stone is heated to a high enough temperature, the daughter crystal begins to break down.

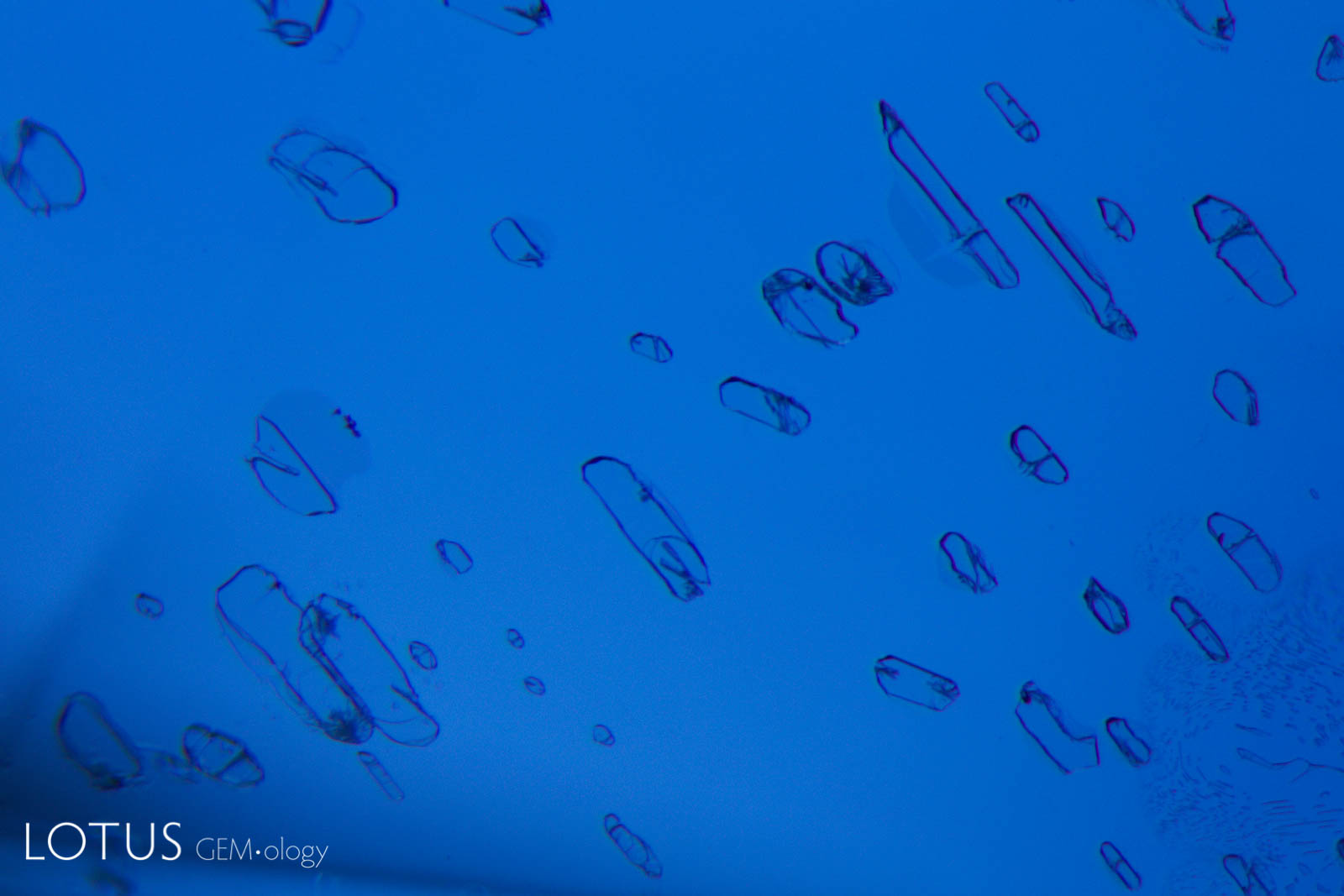

A. Negative crystals in an untreated Mogok, Myanmar (Burma) sapphire in transmitted light.

B. When illuminated with a fiber optic light from above, small exsolved plates become visible, in addition to the negative crystals.

A. Transparent crystals, seen at left in transmitted light, can be hard to distinguish from negative crystals.

B. However when observed between crossed polars (right), the interference colors reveal their doubly refractive nature. Untreated sapphire from Sri Lanka.

A. With oblique fiber optic illumination, primary rutile crystals in an untreated Madagascar ruby show a dark red color.

B. In reflected light, we can also see that they display a submetallic luster where they were cut through on the surface.

A. This ruby from Madagascar contains a large cavity with a mobile CO2 bubble.

B. As the gem is rotated in the stoneholder, the bubble moves. Such fluid-filled cavities (generally filled with liquid and gaseous CO2) cannot withstand heat treatment and thus are proof of natural origin.

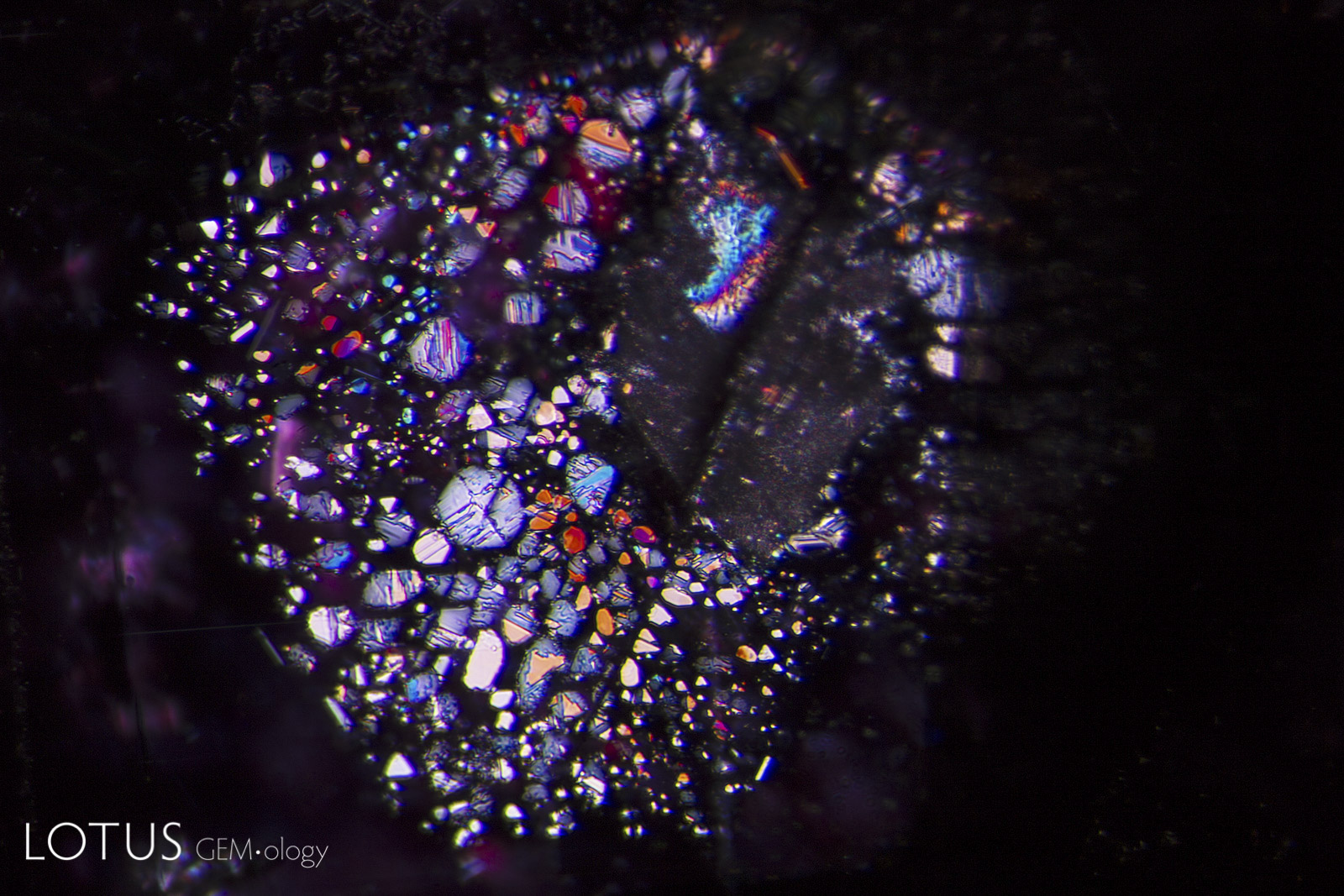

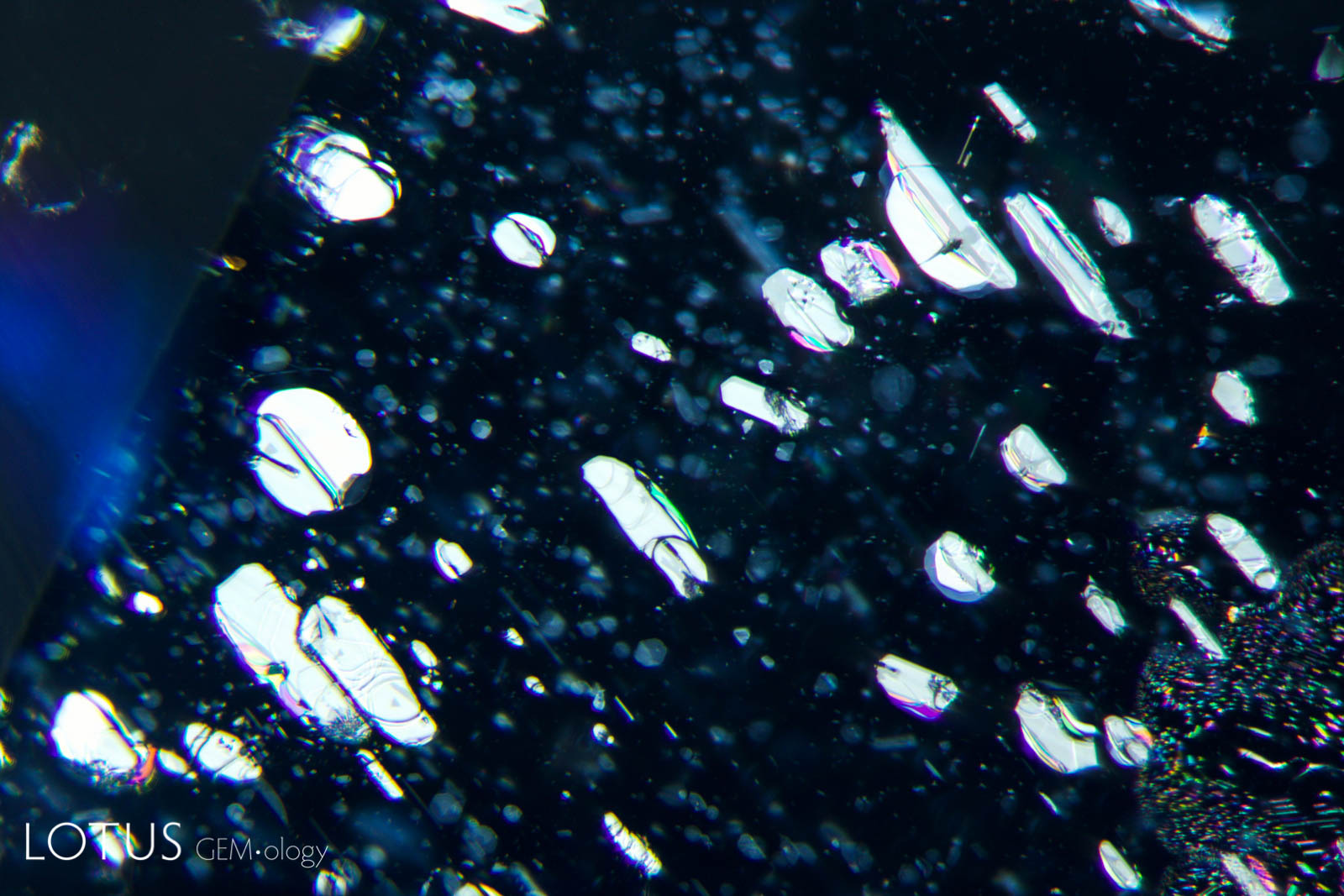

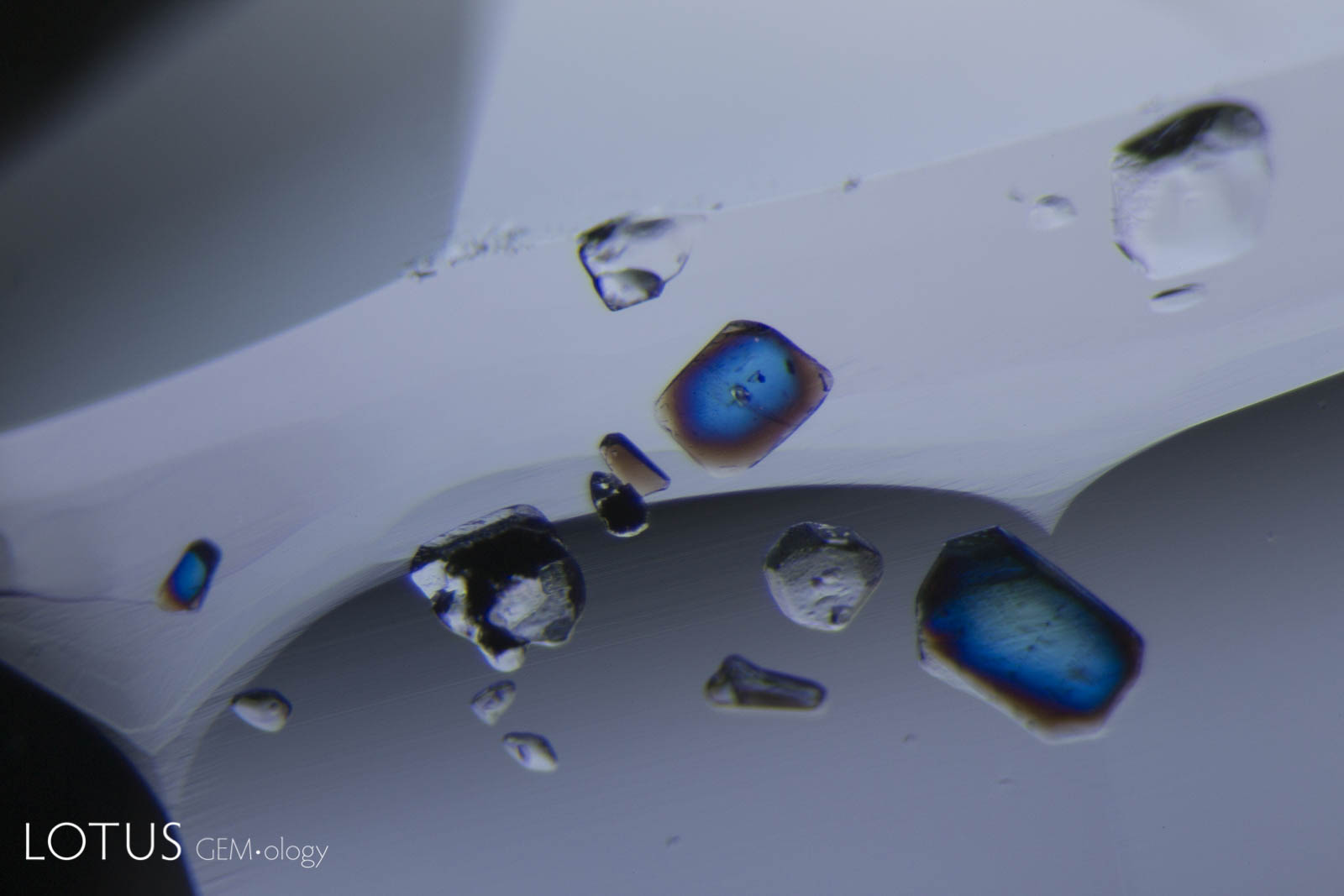

A. Birefringent crystals light up in different colors in this sapphire from Sri Lanka when viewed between crossed polars.

B. Note the change in appearance of the included crystals when viewed between parallel polars.

A. Partially healed "fingerprint" in a Sri Lankan sapphire, before heating. Note the pristine nature of the tiny negative crystals.

B. Heating of such a fingerprint causes tiny microfractures as the negative crystals burst, creating shiny discoid areas and a hazy appearance.

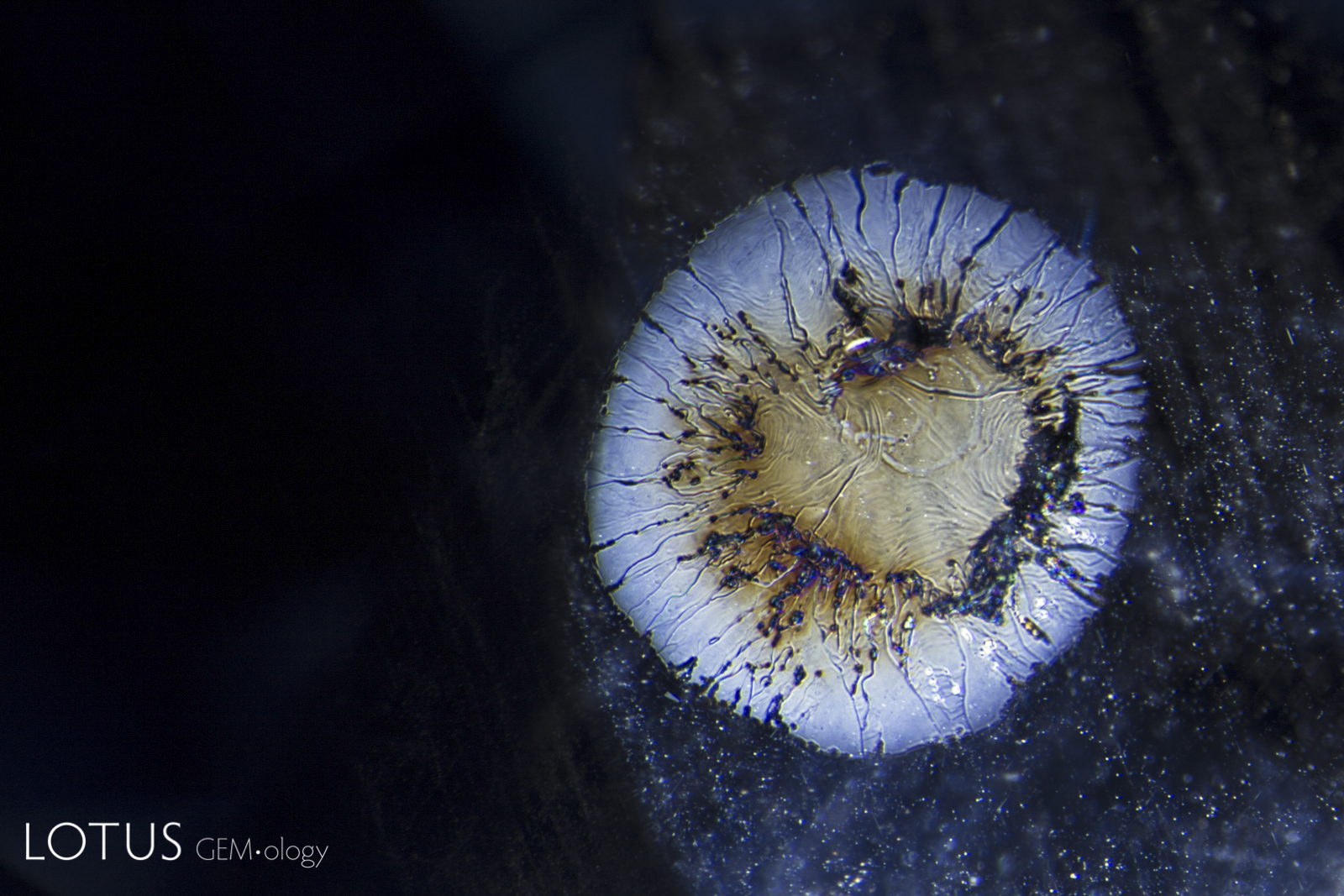

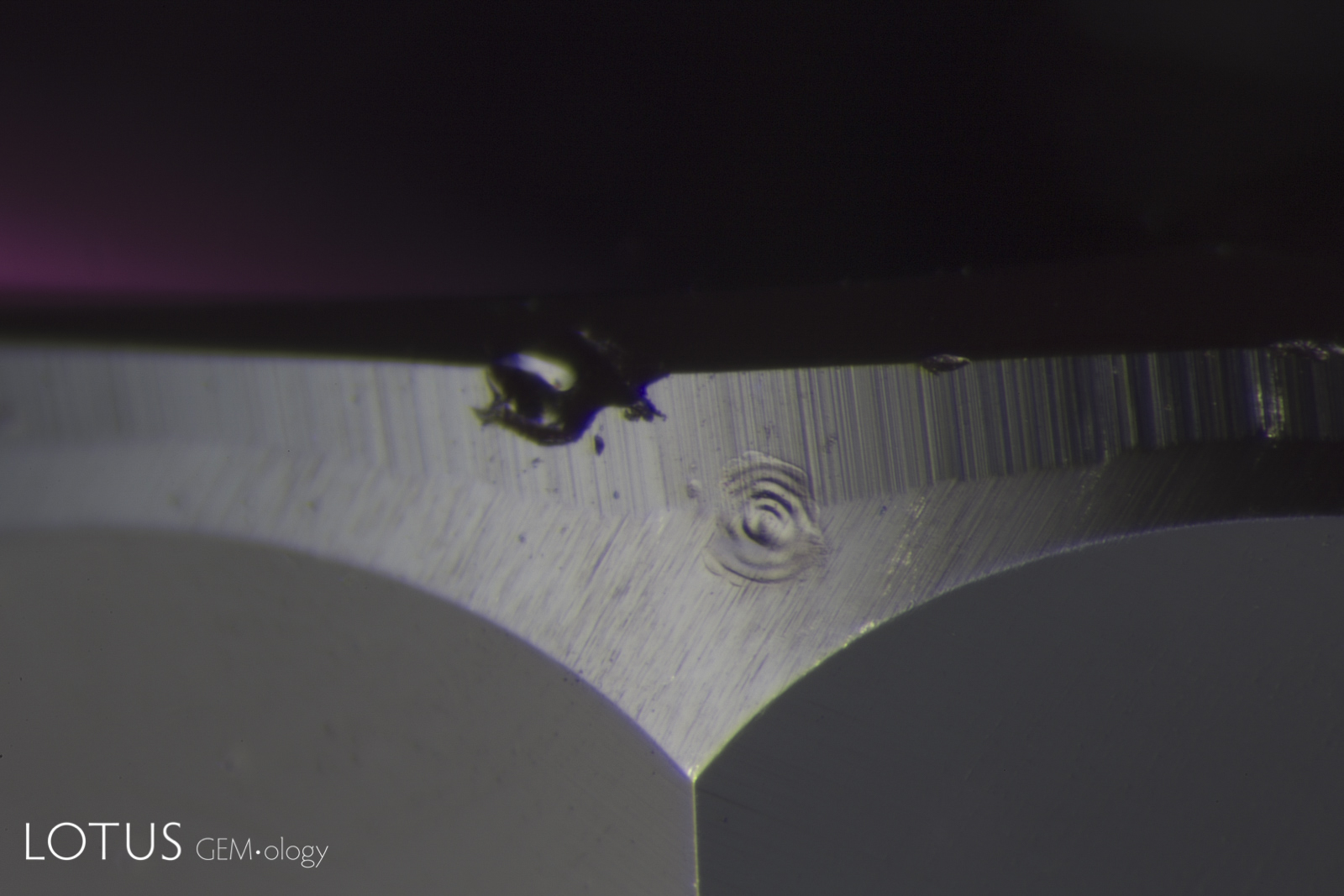

A. Laser-Induced-Breakdown-Spectroscopy (LIBS) is used by some gem labs to test for beryllium. Unlike Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectroscopy (LA-ICP-MS), the surface is actually melted (rather than ablated), producing the circular rippled mark we see in the center of the girdle on the stone at left.

B. In contrast, LA-ICP-MS ablates the gem, producing the symmetrical holes we see in the image at right.

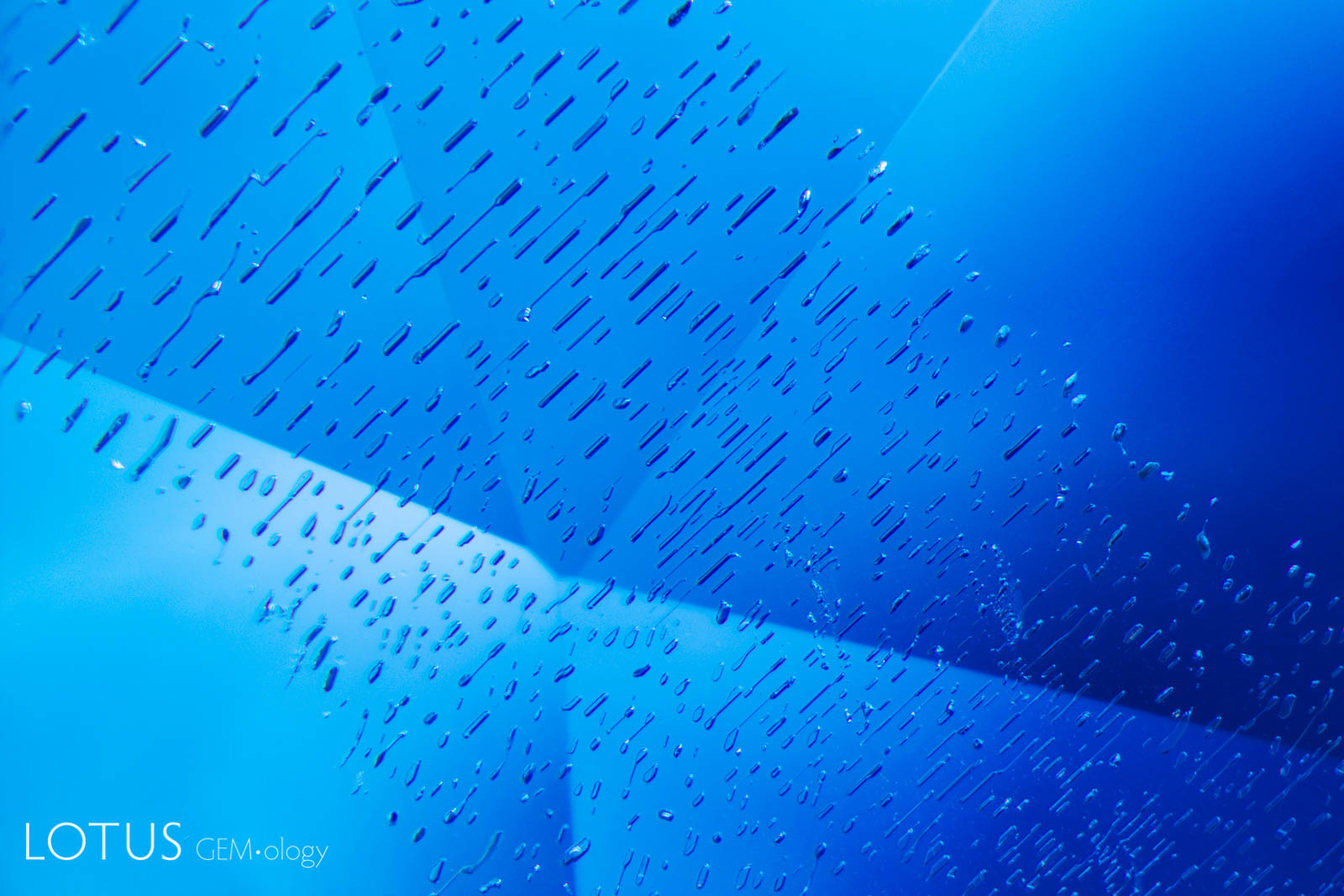

A. Clouds of undissolved rutile silk decorate the inner world of this sapphire, providing evidence that the stone has not been subject to heat treatment.

B. When a silky sapphire is heated to a high enough temperature, titanium from the rutile silk is forced into solid solution, coloring the stone blue. But the silk may also contain other elements that cannot dissolve into sapphire so readily, leaving behind silk “skeletons,” as shown here.

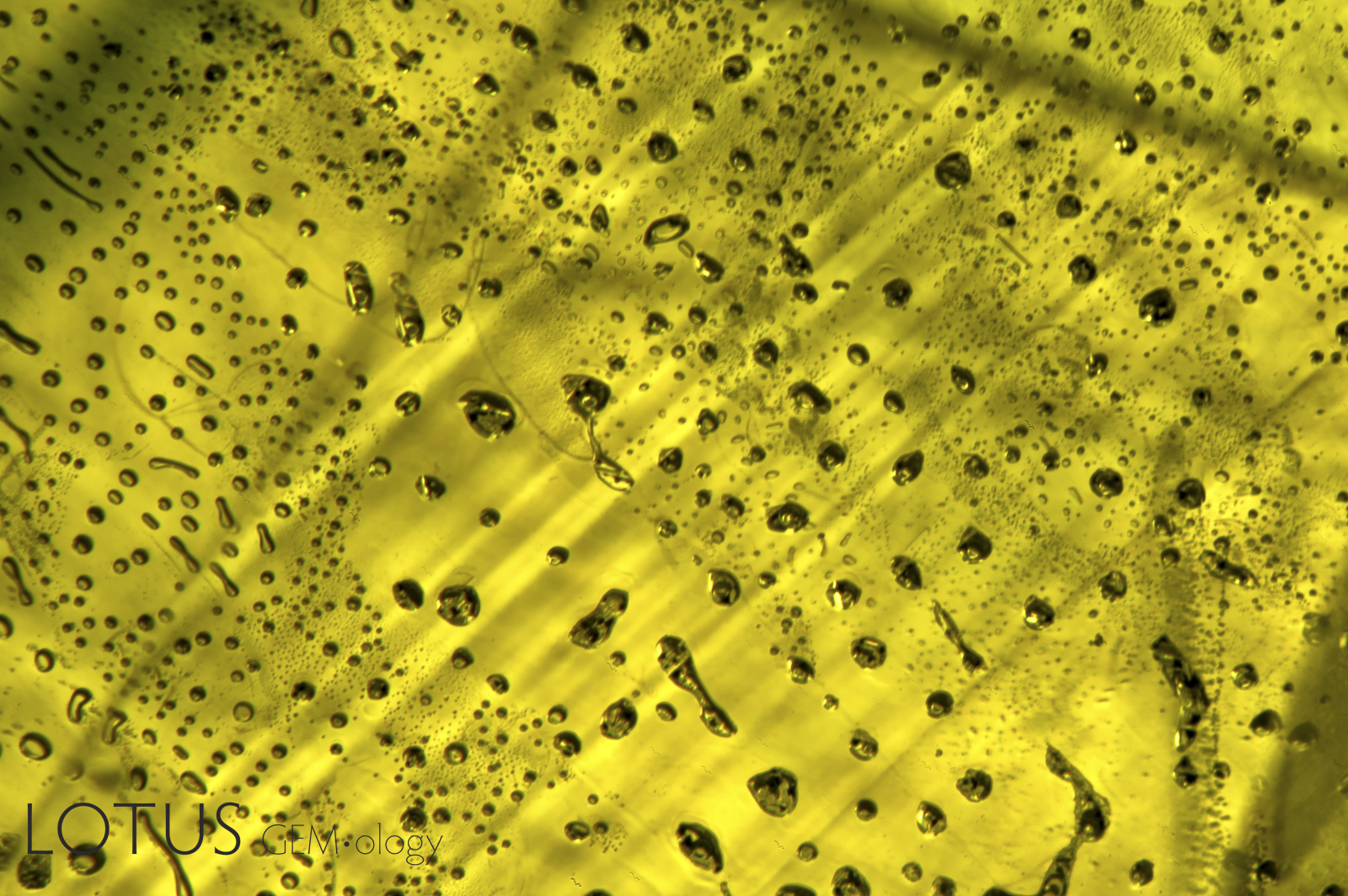

A. A petroleum-filled cavity in quartz. In light field, the petroleum displays a yellow appearance.

B. The same petroleum-filled cavity in quartz, this time illuminated with a longwave ultraviolet (UV) torch. Under longwave UV, the petroleum fluoresces a chalky yellowish white.

A. Fine exsolved particles in a heated Sri Lankan yellow sapphires. When such stones are heat treated, magnesium diffuses into the sapphire, creating yellow-producing trapped-hole color centers. The result is color concentration around the particles, a process dubbed “internal diffusion” by gemologist, John Koivula.

B. The same stone when viewed with diffuse light-field illumination. Here you can clearly see the color concentrations around the particles.

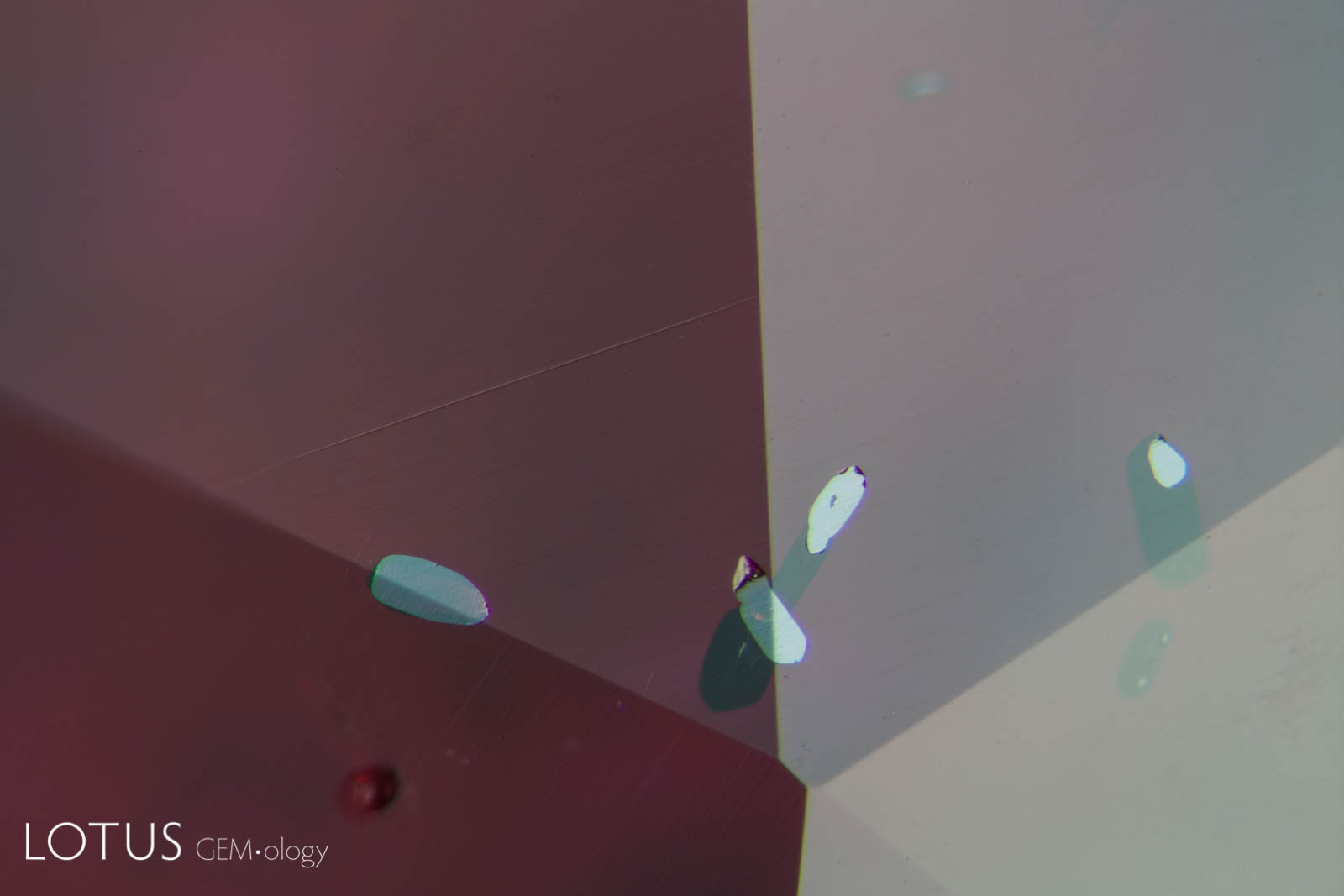

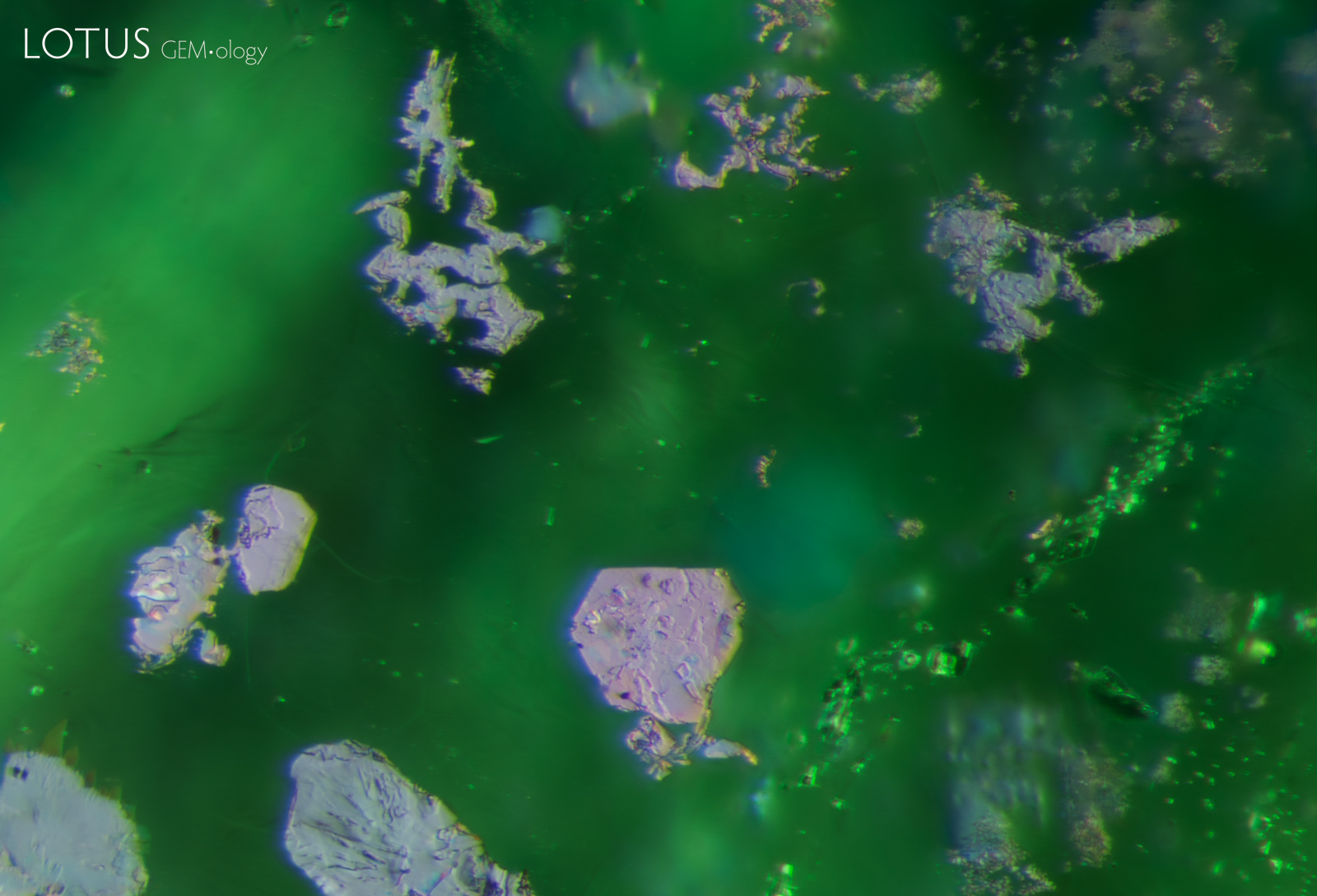

A. In this beryllium-diffused green sapphire, the high-temperature heating has healed a former fissure and the pockets of residue show clear rounding and necking down. Some also show shrinkage bubbles as the glassy material cooled and thus occupied less space, creating the bubble in the cavity. Angular growth zoning can be seen in the background.

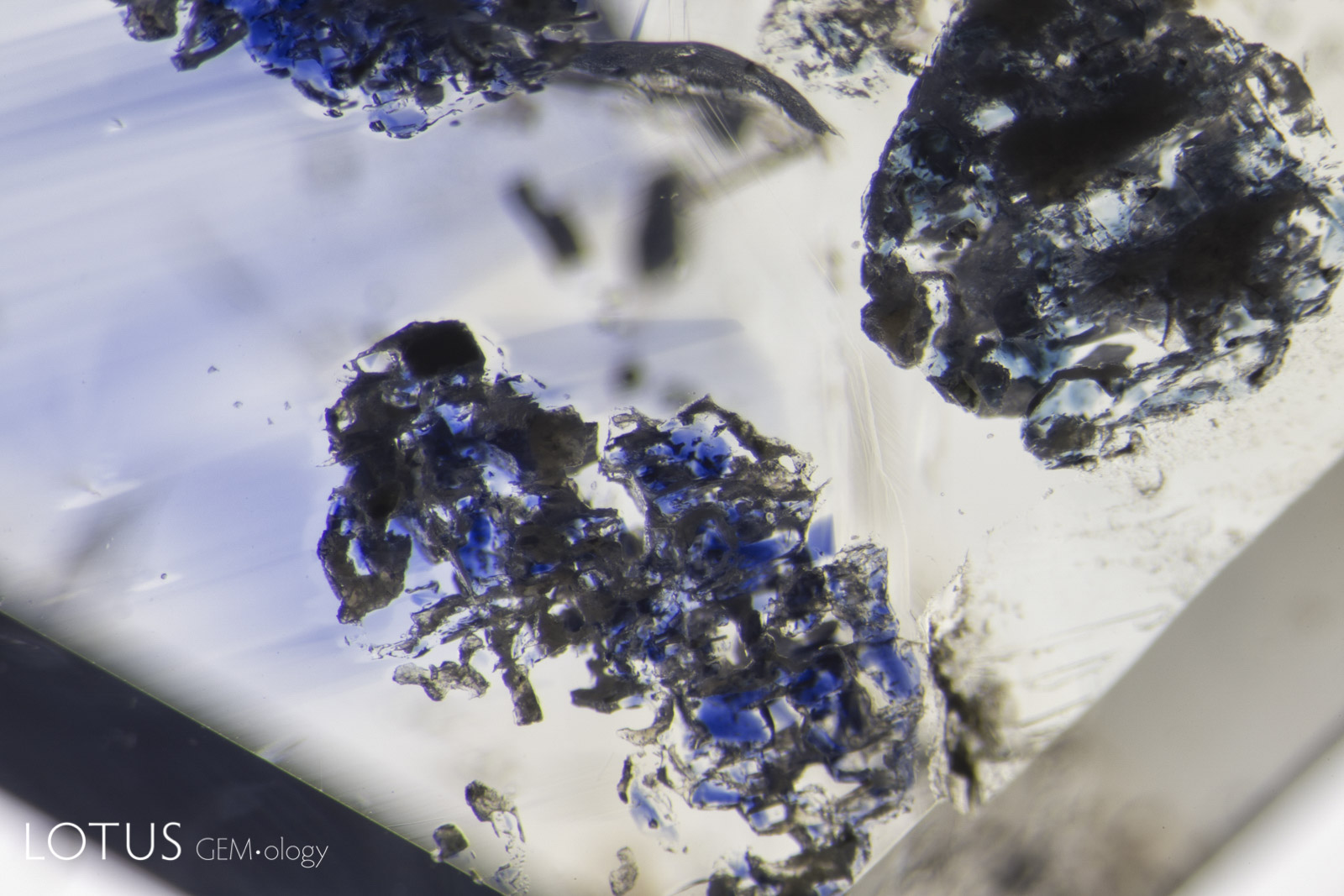

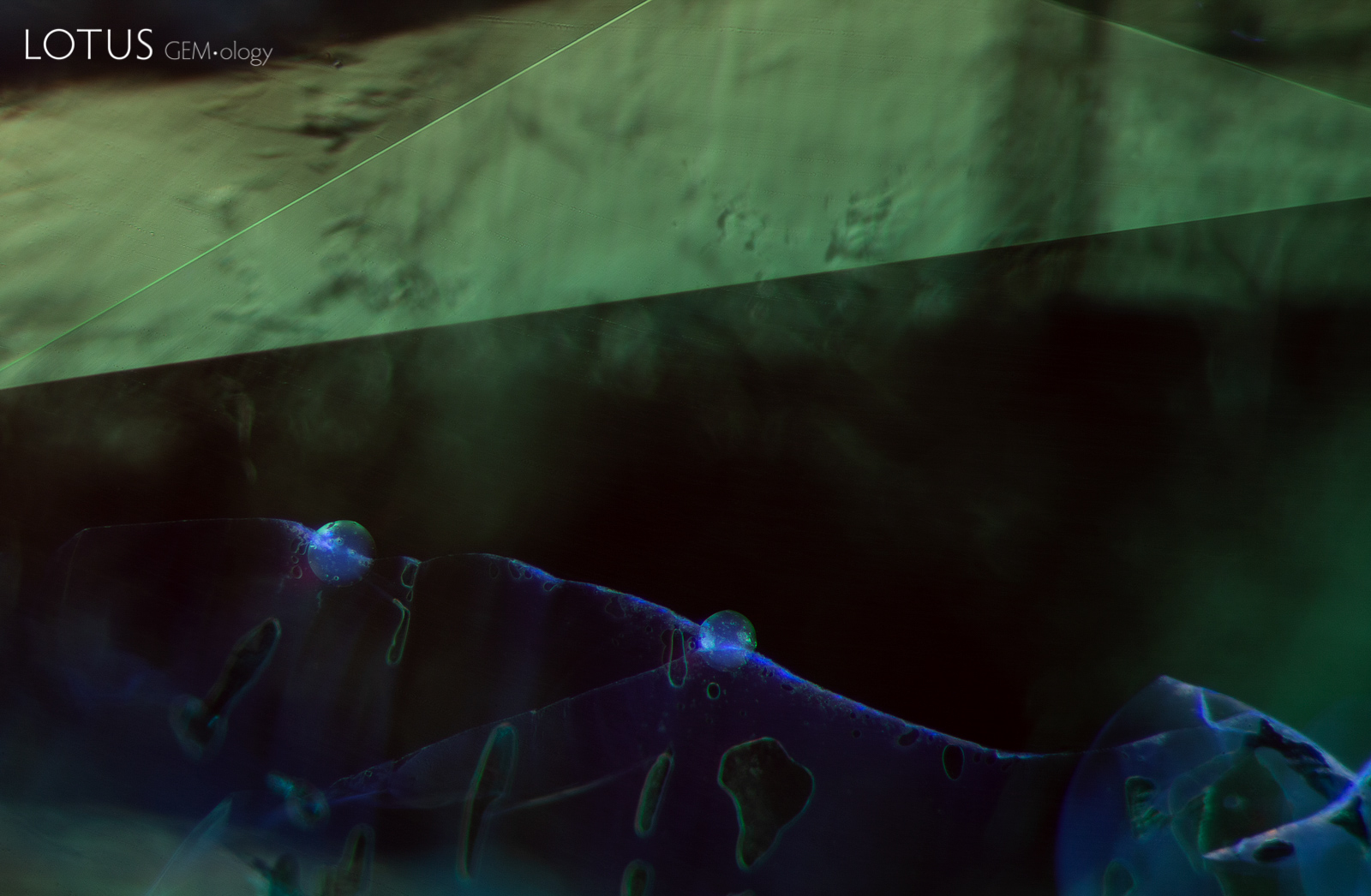

B. Extremely high temperatures are required for beryllium diffusion. In some cases, heat treatment may dissolve the corundum and that dissolved alumina may redeposit as synthetic corundum on the surface, as shown here.

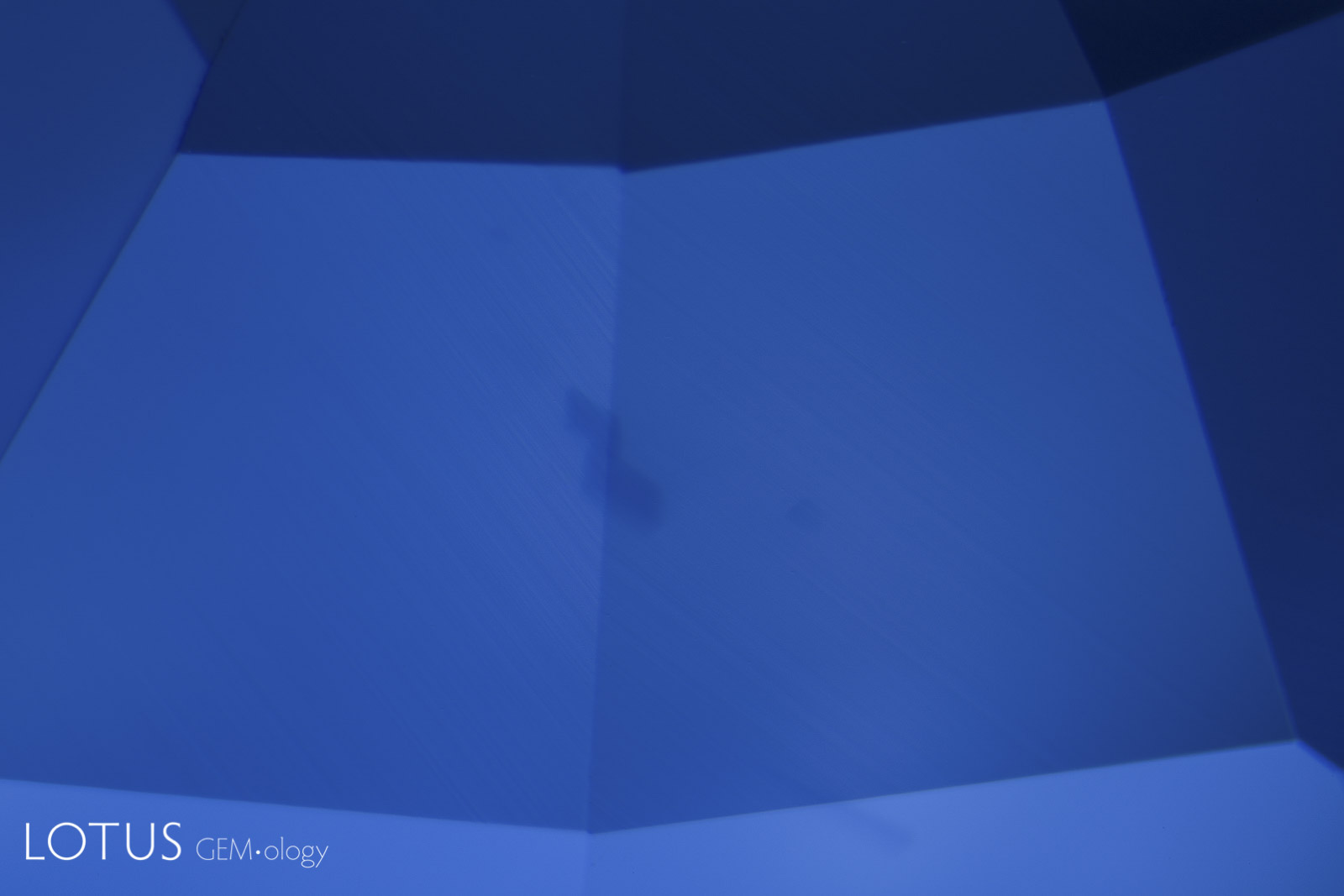

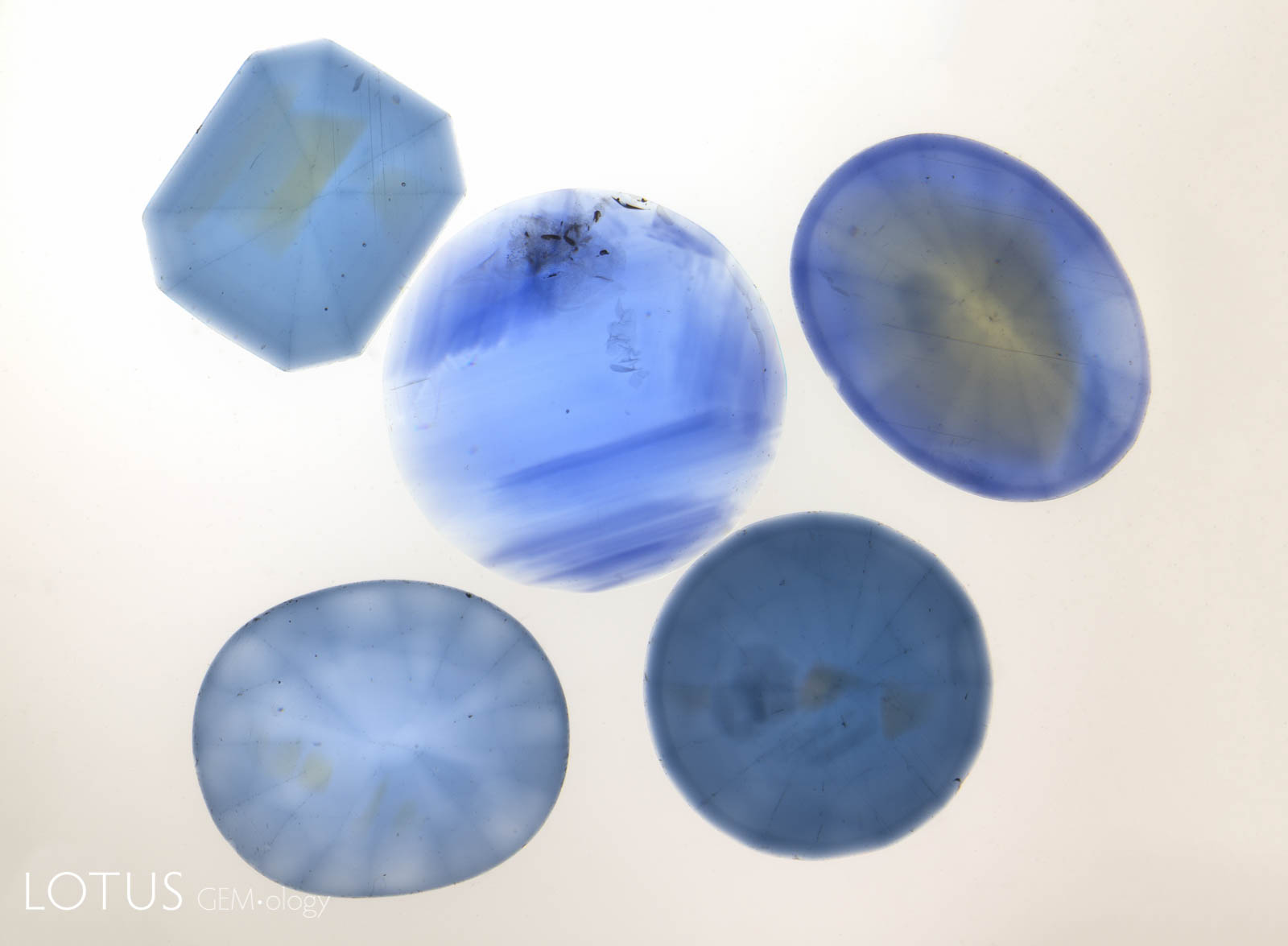

A. Due to the size of the titanium ion, bulk diffusion with titanium achieves only shallow penetration (up to 0.5 mm). The result is color concentrations at the girdle and facet junctions, as shown above.

B. In contrast, beryllium (Be) diffusion, which produces a yellow color, can result in much deeper penetration because the Be ion is much smaller. Extending the heating time can even diffuse Be completely through the gem. While some stones may display a surface-conformal color rim (as shown above), Be-diffused stones do not show the darker girdle and facet junctions that are found in Ti-diffused stones.

C. Five sapphires viewed in immersion against a diffuse white background. The center stone is natural, while the four stones surrounding it are Ti-diffused; note the dark girdles and facet junctions of the Ti-diffused stones.

D. Beryllium diffusion results in a surface-conformal color rim.

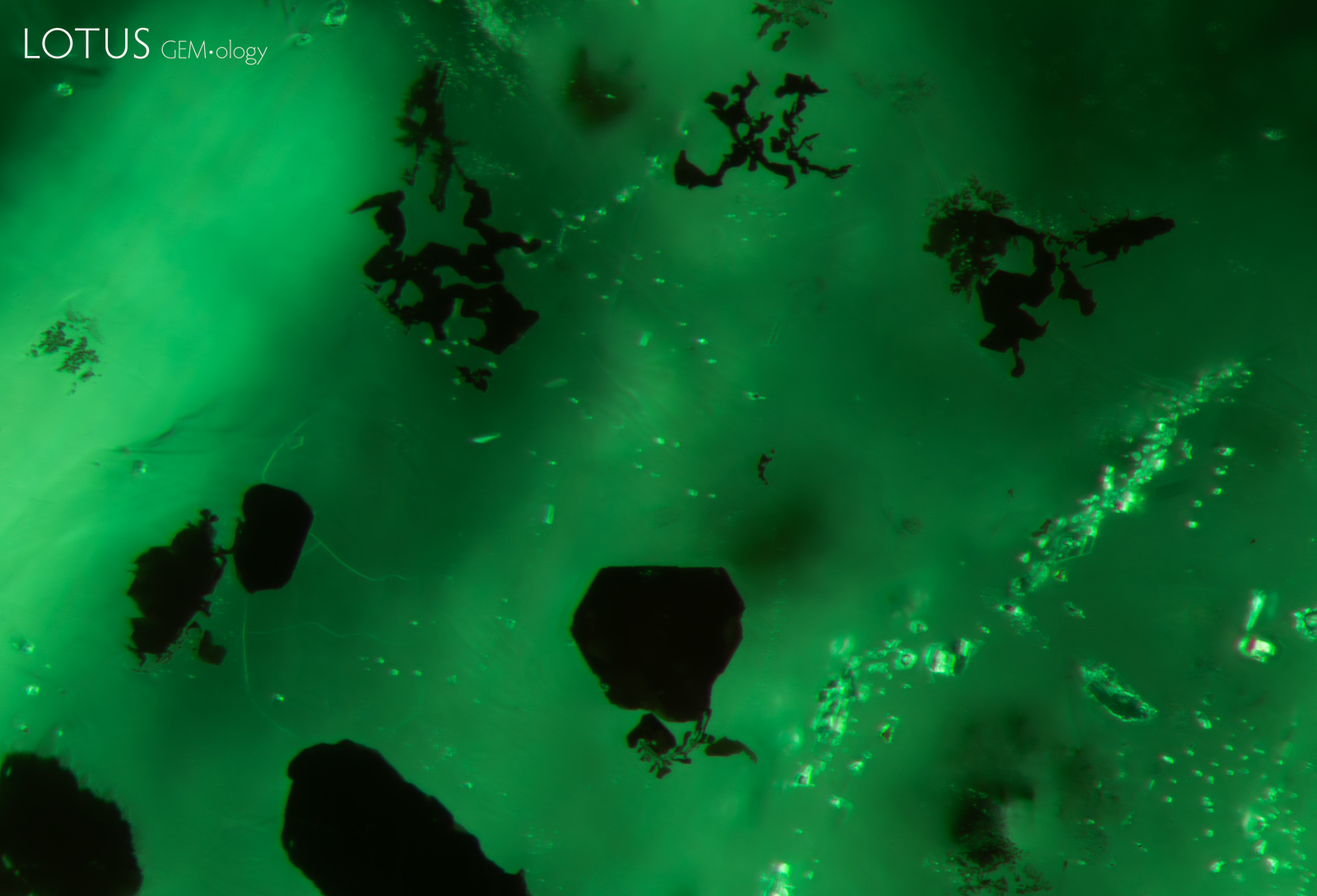

A. Dark platelets (probably ilmenite) in an emerald from Zambia, as viewed in dark field illumination. Specimen courtesy Gemfields.

B. When viewed with an overhead fiber-optic light, as seen here, the platelets display a an iridescent metallic appearance, revealing details that are invisible in dark field. Specimen courtesy Gemfields.

A. When this emerald was gently warmed with a hot point, droplets of resin began to leak out of the fissures. The droplets can be best observed with reflected light.

B. When illuminated with a long wave UV torch, the areas with oil/resin display a chalky appearance, particularly where two large round droplets are concentrated.

Note

The title graphic was inspired by master photomicrographer John Koivula, who demonstrated this technique of image mirroring to create aesthetic patterns at the International Gemmological Conference in Brazil in 1987.