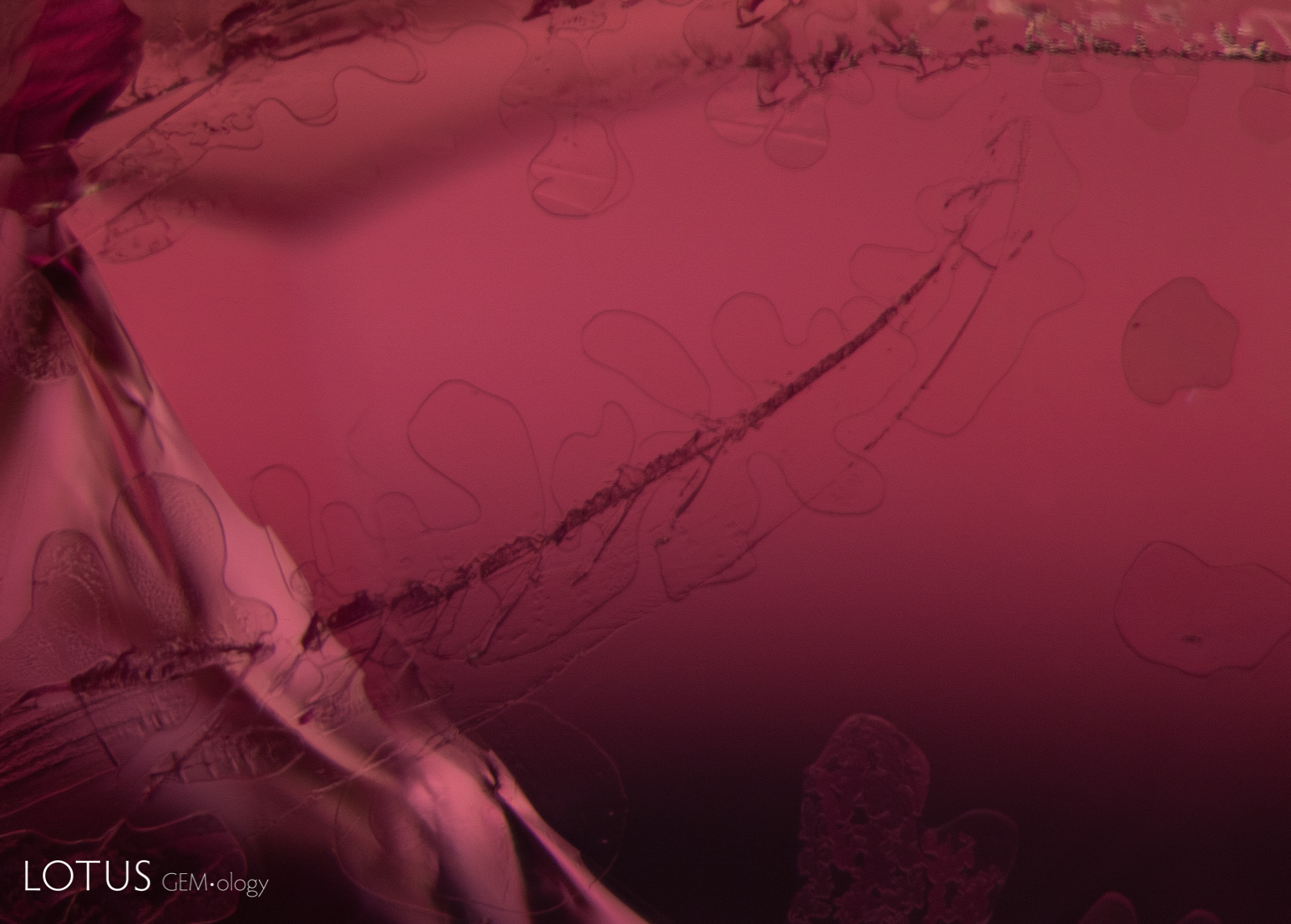

A. Viewed in transmitted light, the fissure in this ruby displays a subtle dendritic pattern.

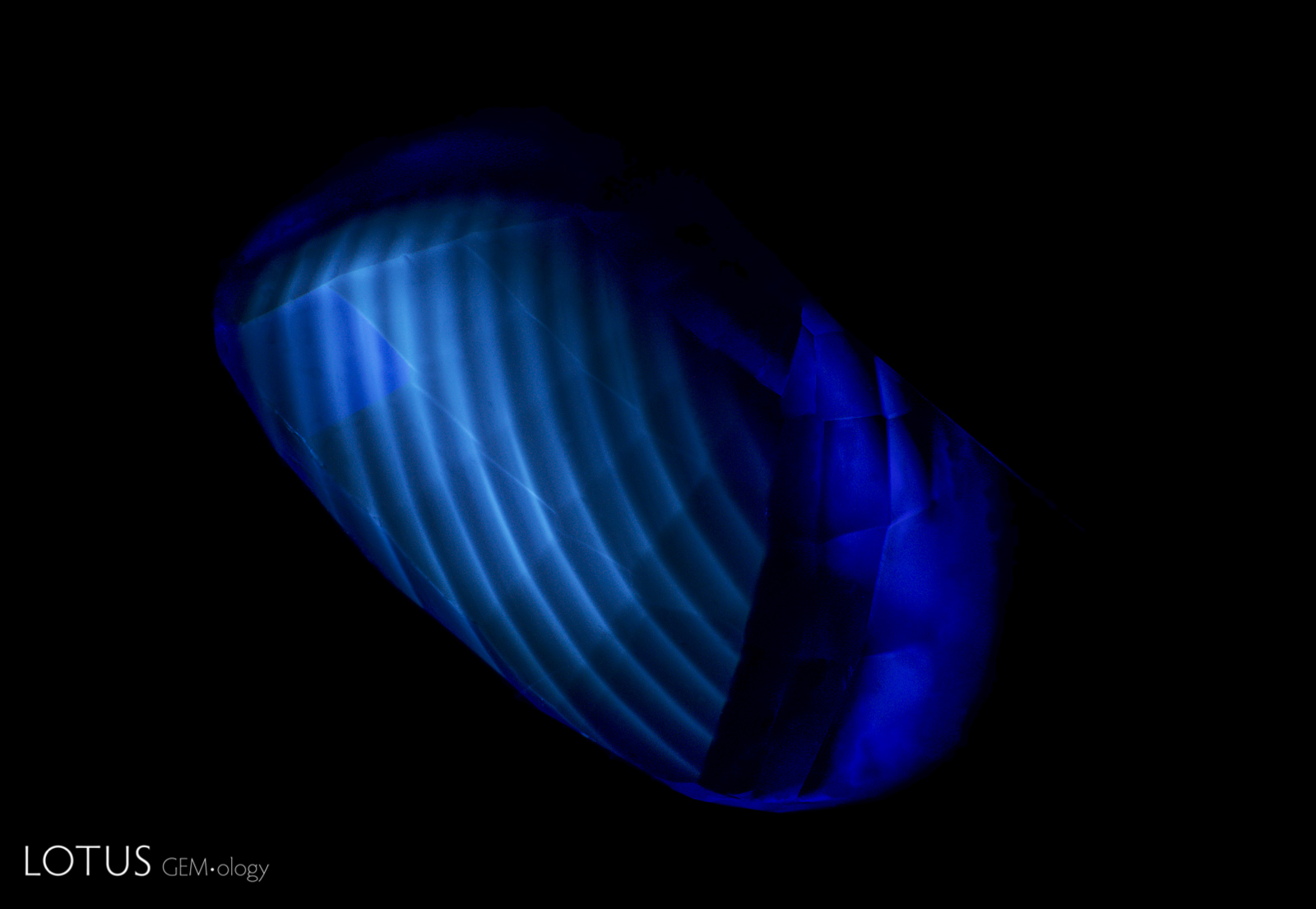

B. When the same fissure is illuminated with a longwave UV torch, a dendritic pattern where filler is present can be easily seen. The glass filling in this instance fluoresces a chalky blue. Oils and resins in filled fissures may also display similar fluorescence.

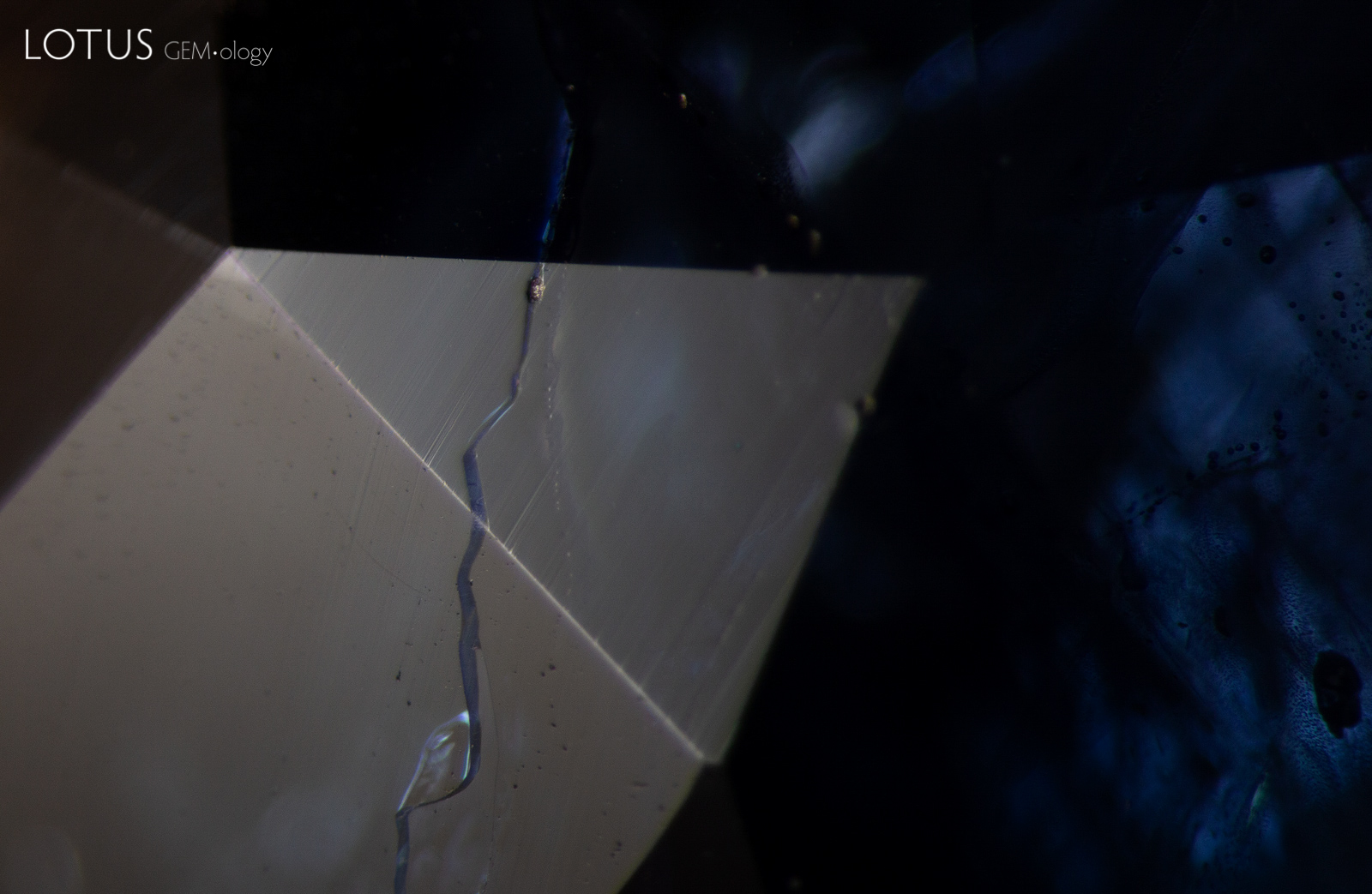

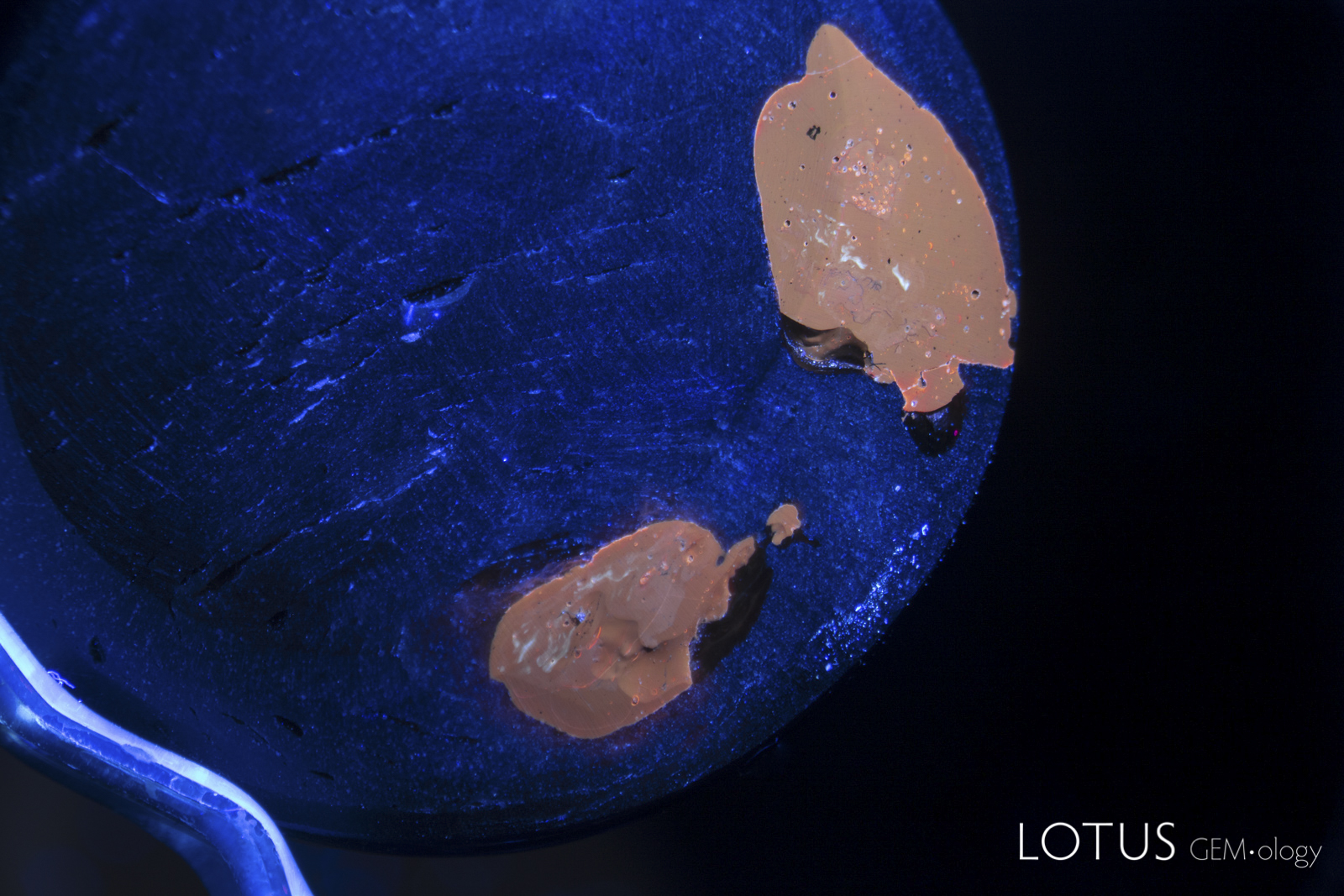

A. When observed with diffuse reflected illumination from a fiber optic light guide, the surface of this sapphire shows a glass filled fissure of lower luster.

B. Once exposed to longwave ultraviolet light from a torch, the filling in this fissure becomes evident, displaying an orange glow.

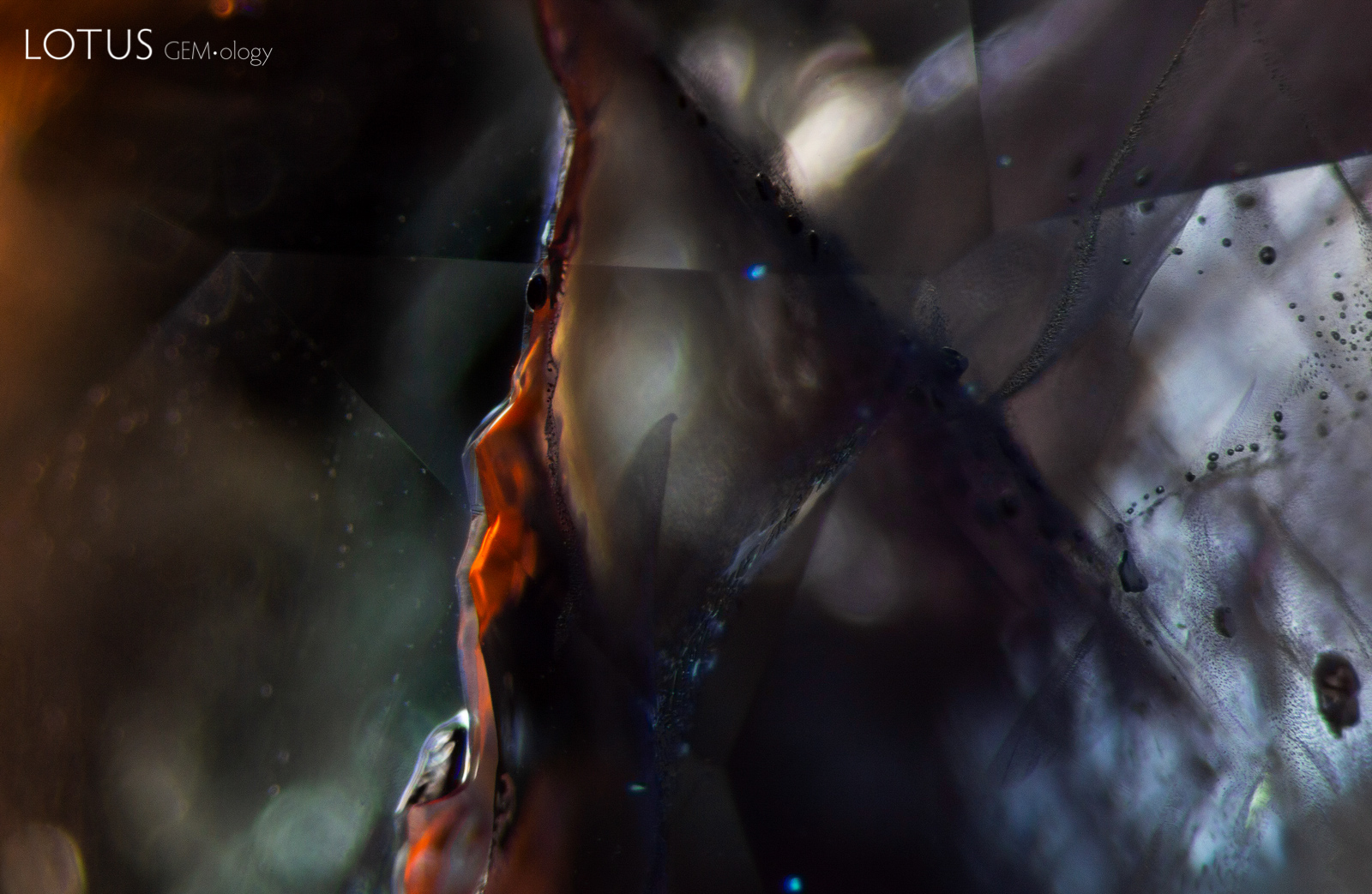

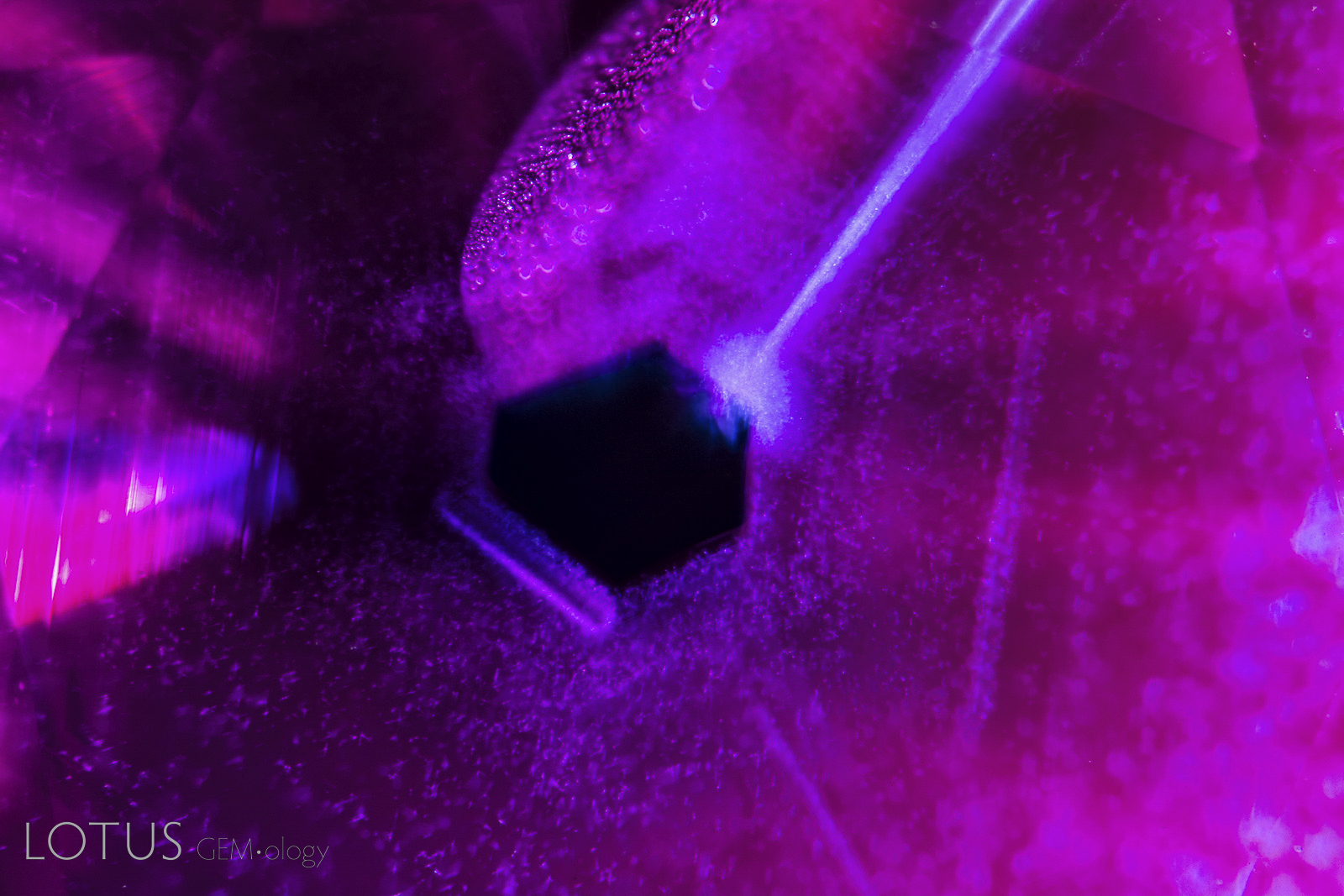

A. This ruby featured a surface cavity filled with a hardened resin, with gas bubbles clearly visible within the filler.

B. When illuminated with a long wave UV torch, the filler in this ruby becomes easy to spot due to its chalky fluorescence.

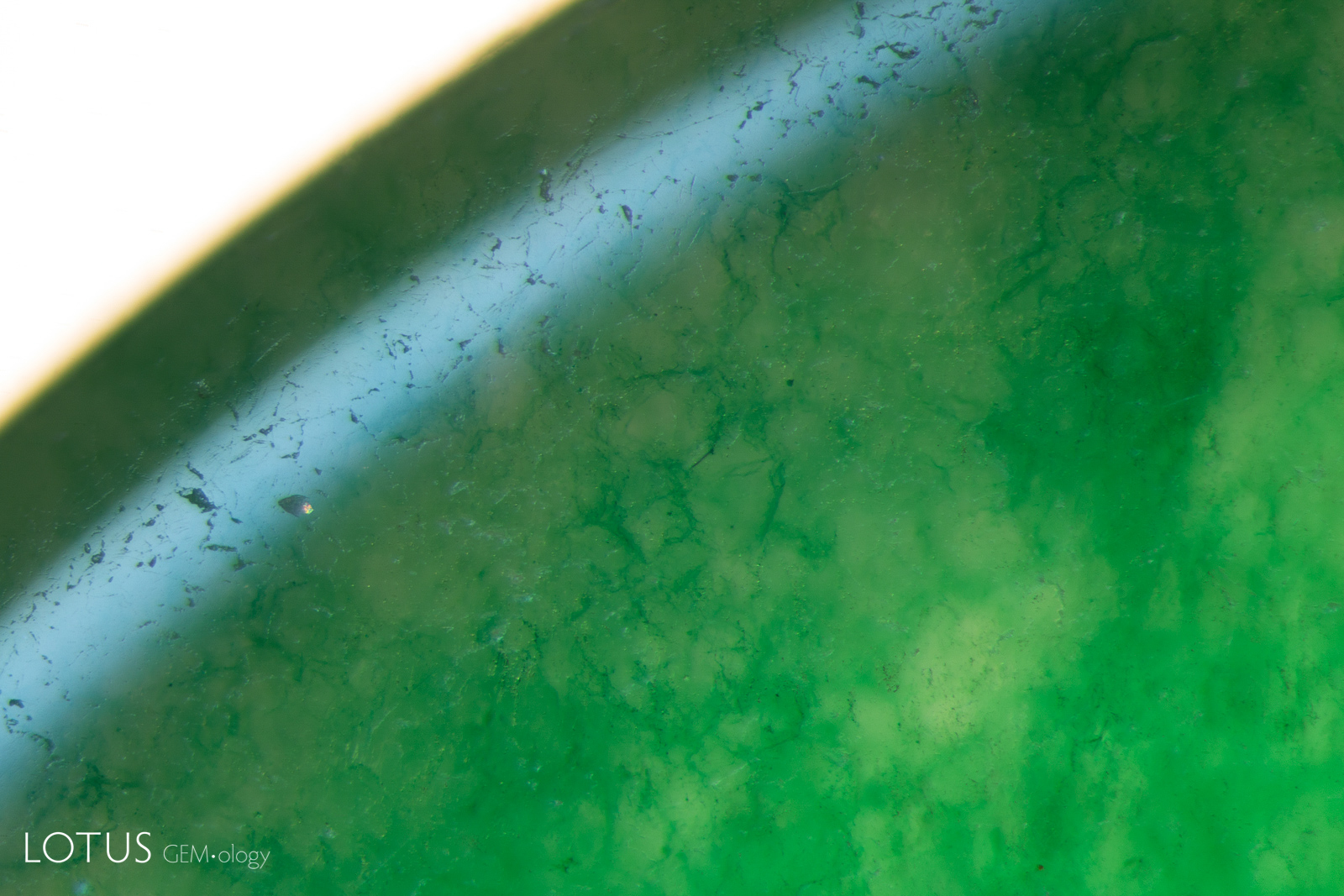

A. The green color concentrations in the fissures of this quartzite suggest that it has been treated with green dye. This type of material is often used as an imitation of fei cui. Specimen courtesy Jeffery Bergman.

B. This piece of quartzite was dyed green to imitate fei cui. The green color concentrations in the fissures reveal that it was dyed. Specimen courtesy Jeffery Bergman.

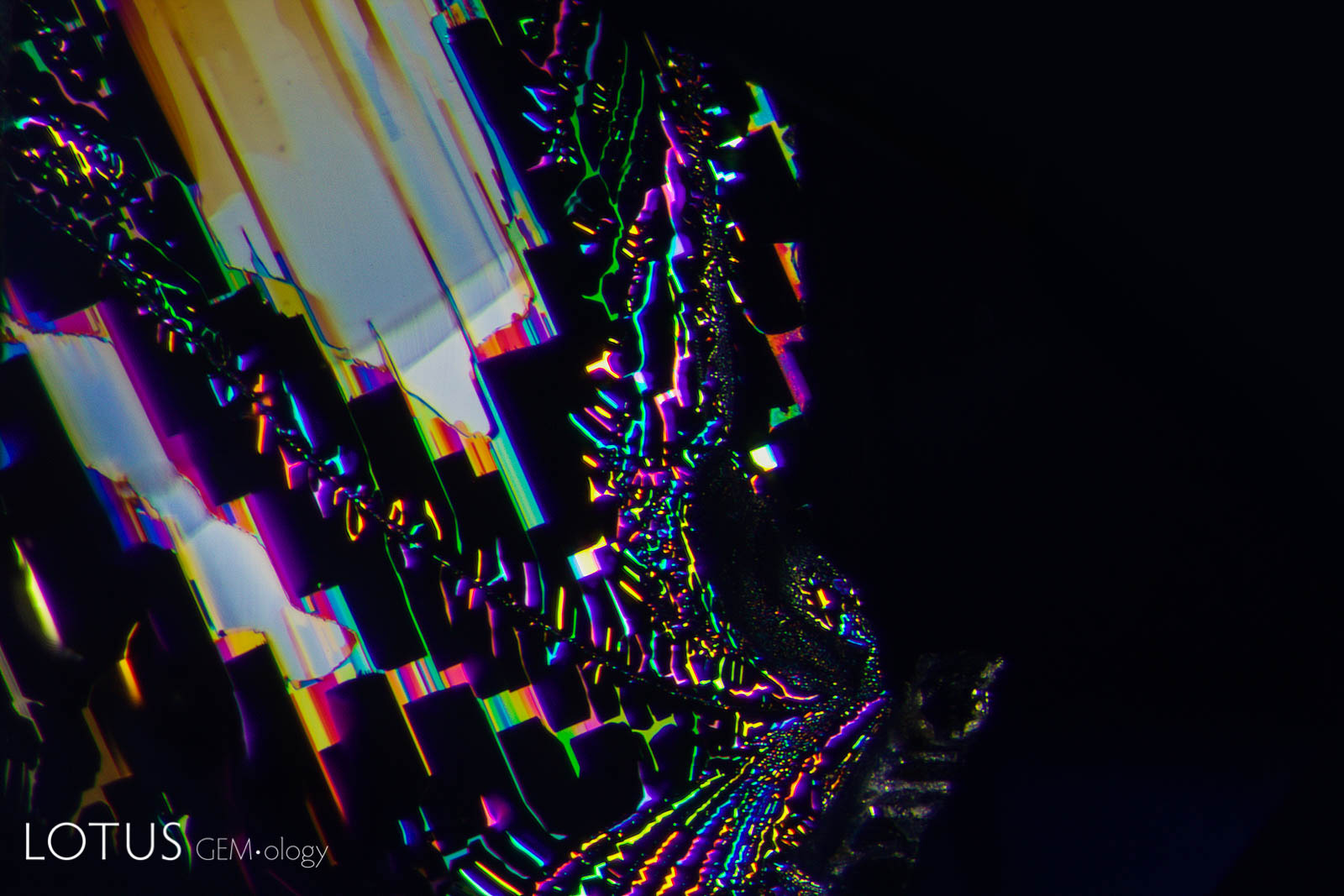

A. A clinochlore crystal in a spinel host displays a rainbow of interference colors when observed between crossed polars. When the polarizing plates are rotated the interference colors change.

B. Rotating the analyzer causes the interference color to change.

A. This emerald contained a filler to help hide fissures in the stone. In dark field illumination, the filler is not easy to see.

B. By shining a longwave UV torch on the stone, the filled areas become immediately apparent with a chalky appearance. We can also see many small bubbles in the filled areas.

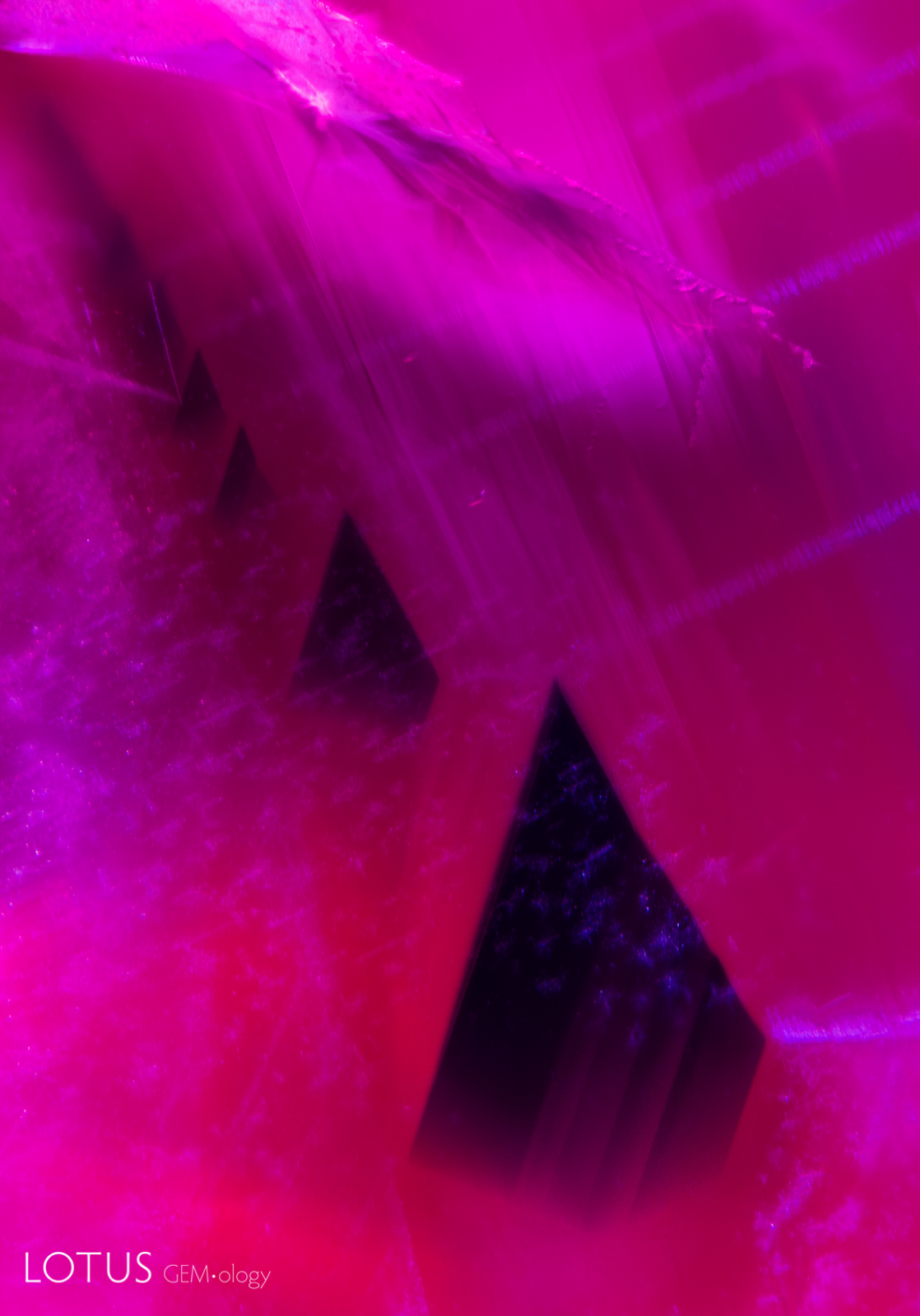

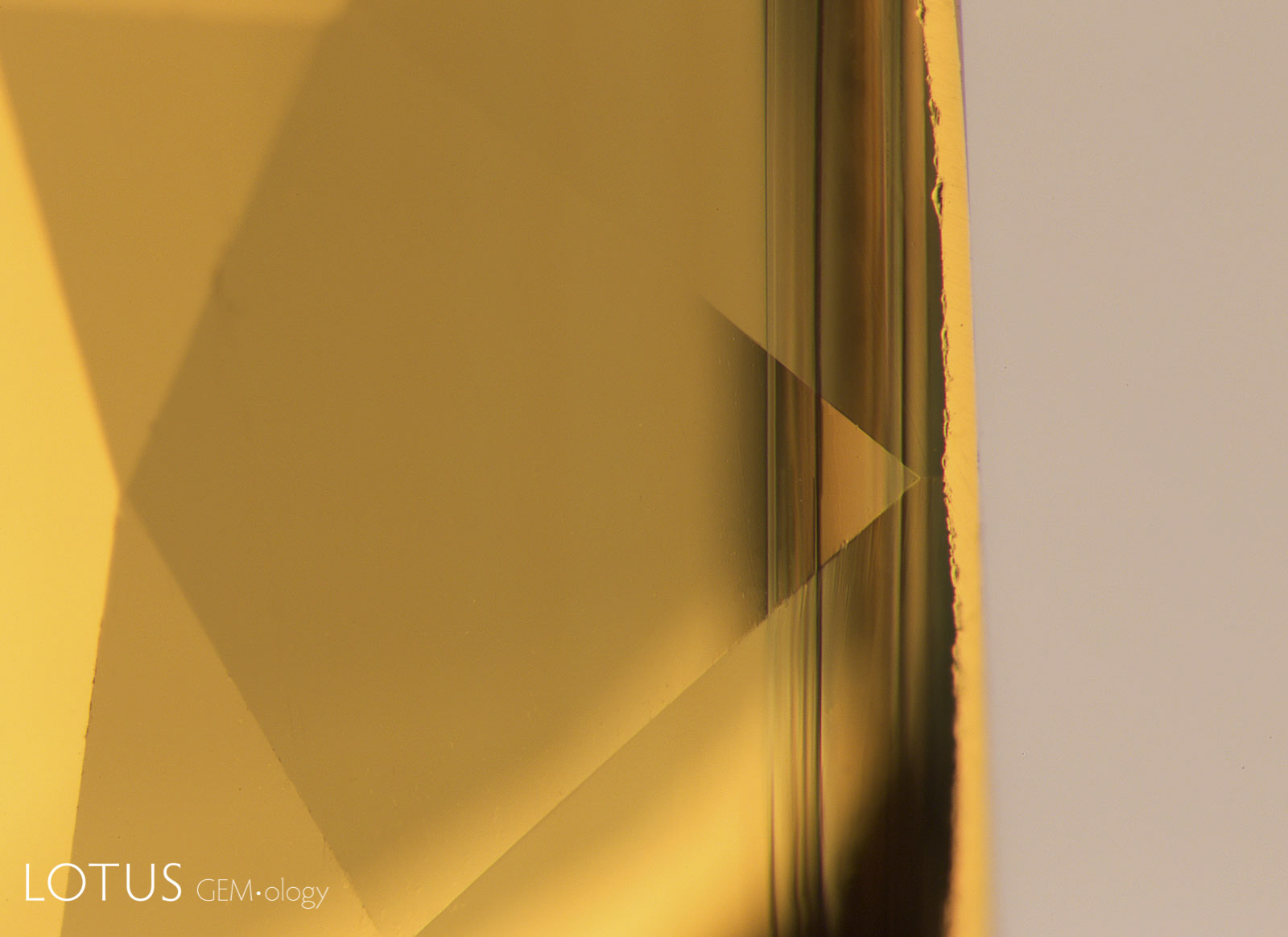

A. Rose channels meeting at 86.1/93.9° angles in this sapphire create a striking geometric appearance. These follow the edges of the rhombohedron faces and thus are oblique to the c-axis, unlike rutile/hematite/ilmenite silk which unmix in the basal plane (perpendicular to the c-axis).

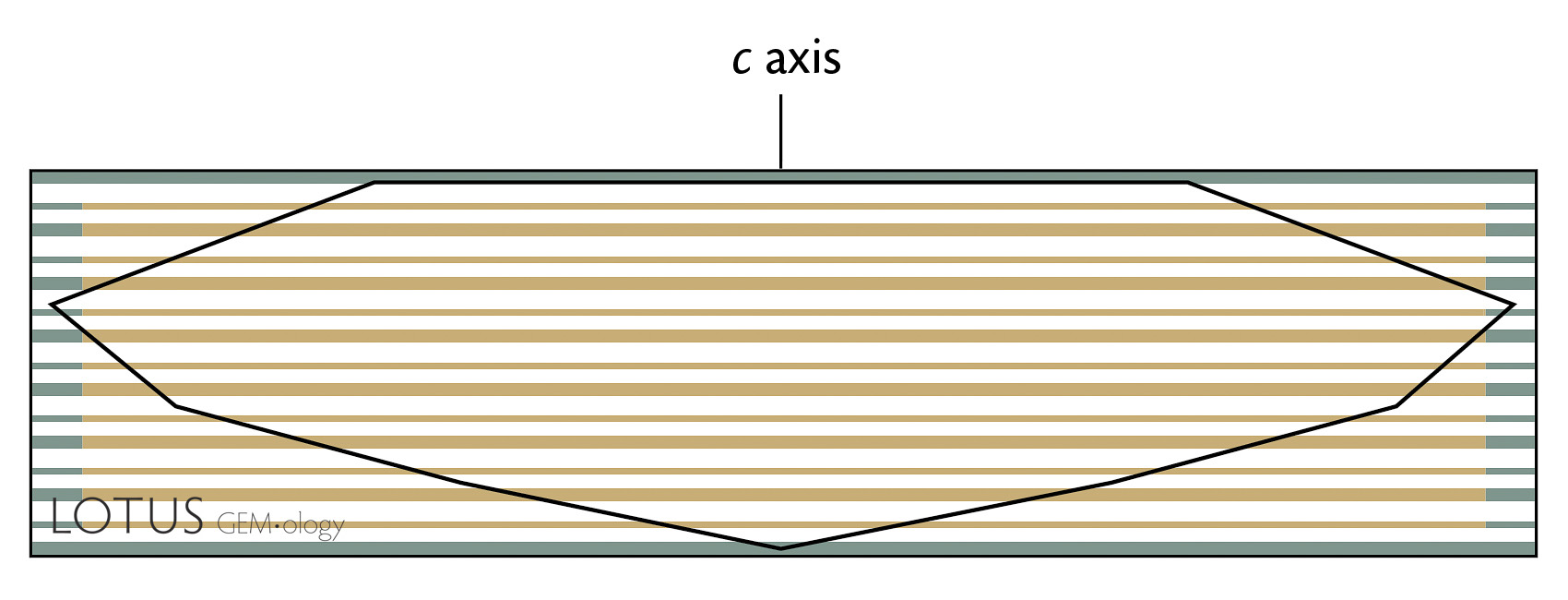

B. Two corundum crystals, each of which displays the hexagonal prism, basal pinacoid and rhombohedron faces. Polysynthetic twinning and Rose channels form along the rhombohedron faces (left example), while the silk that creates star stones (rutile/hematite/ilmenite) unmixes in three directions parallel to the hexagonal prism in the basal plane (right example).

C. Rose channels are often confused with rutile silk in corundum, but they are easily distinguished as they run in entirely different crystallographic directions. Rutile silk unmixes in three intersecting directions (60/120°) parallel to the faces of the hexagonal prism in the plane of the basal pinacoid. In contrast, Rose channels form parallel to the edges of the rhombohedron, in three directions, but only two in the same place. They intersect at 86.1/93.9°. This ruby from Rolela, Kiteo, Tanzania shows nice examples.

D. Rutile silk in corundum unmixes in three directions intersecting at 60/120°, parallel to the faces of the hexagonal prism and flattened in the plane of the basal pinacoid, which lies perpendicular to the c-axis.

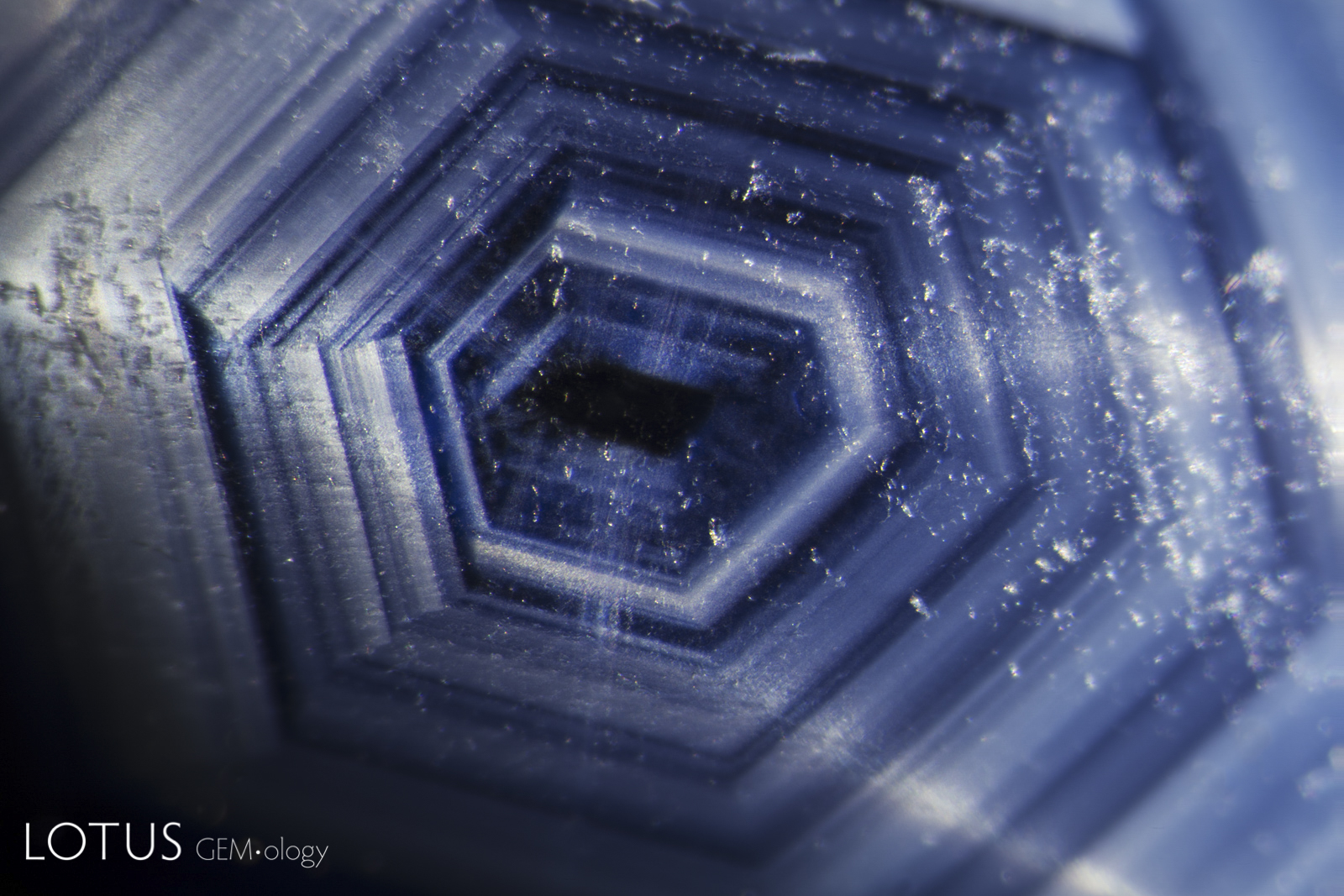

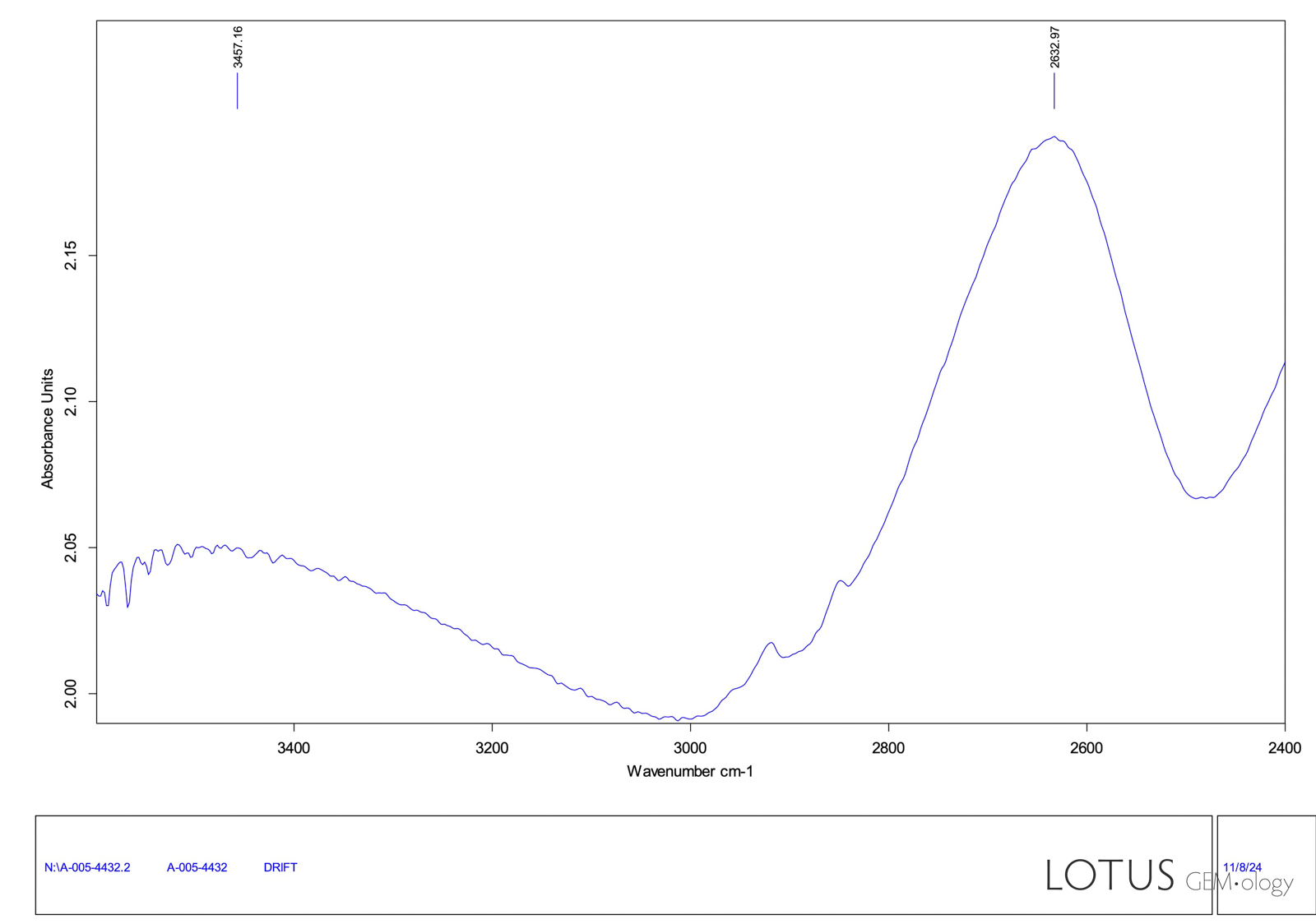

A. In natural crystals, growth occurs outward from a central point. Because crystals have flat faces that meet at angles, the growth zoning will always be parallel to the faces growing at that stage of development. This is vividly displayed in this Australian sapphire, where zones of fine exsolved particles reveal the earlier shape of the crystal.

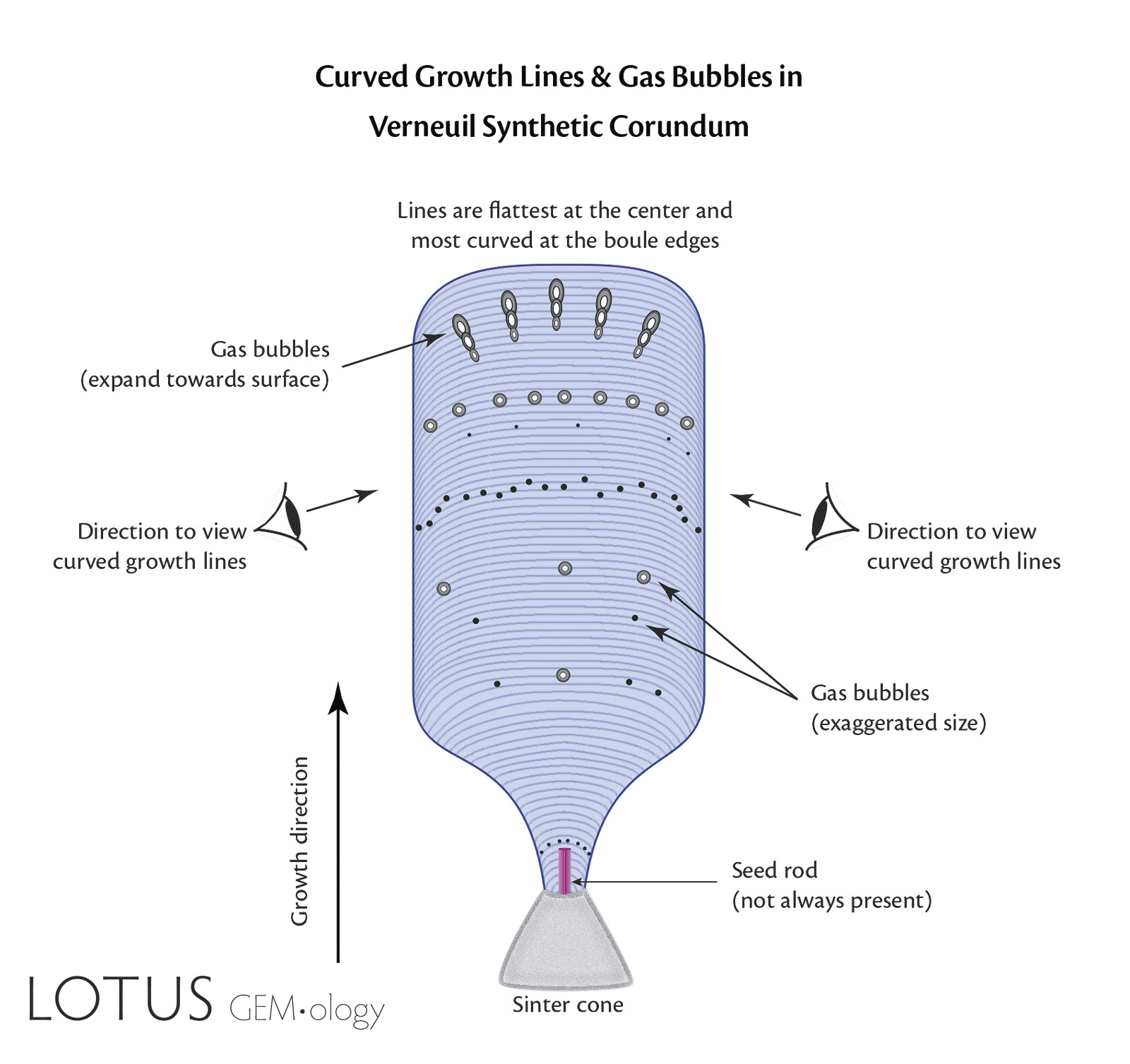

B. In Verneuil (flame-fusion) synthetic corundum, growth takes place from the bottom up in a single direction, beginning with a small molten drop of synthetic corundum at the tip of the sinter cone. That drop has a curved top surface, so when layers of synthetic corundum are added from above, they mimic the curved layers below, producing curved growth lines. These are NOT concentric layers. Gas bubbles are produced when the flame temperature is too hot, causing boiling of the growing boule’s surface in contact with the flame. They expand as they rise towards the surface.

C. Curved color banding in a Verneuil-grown synthetic sapphire.

D. Curved banding is easily spotted in this flame-fusion blue synthetic sapphire when illuminated with the Magilabs deep-UV fluorescence system, a short-wave UV source.

A. This spinel before (left) and after (right) filler removal clearly demonstrates that fissure filling with an oil or resin can have a dramatic impact on the appearance of a gem. This is why it it critical that all gems with fissures be carefully checked for fillers.

B. While fissure filling with oils/resins is most often seen in emerald, this treatment can also have a dramatic impact on the appearance of other gems. The above image shows a tanzanite after filling the fissures with an oil/resin.

C. Removal of the oil/resin makes the fissures far more visible. Contrary to popular belief, the refractive index of the filler does not need to match the gem. Replacement of the air (n=1.0) with an oil or resin (n=~1.55) still provides tremendous clarity enhancement. Because filled gems allow longer light paths, there is also a noticeable improvement in color.

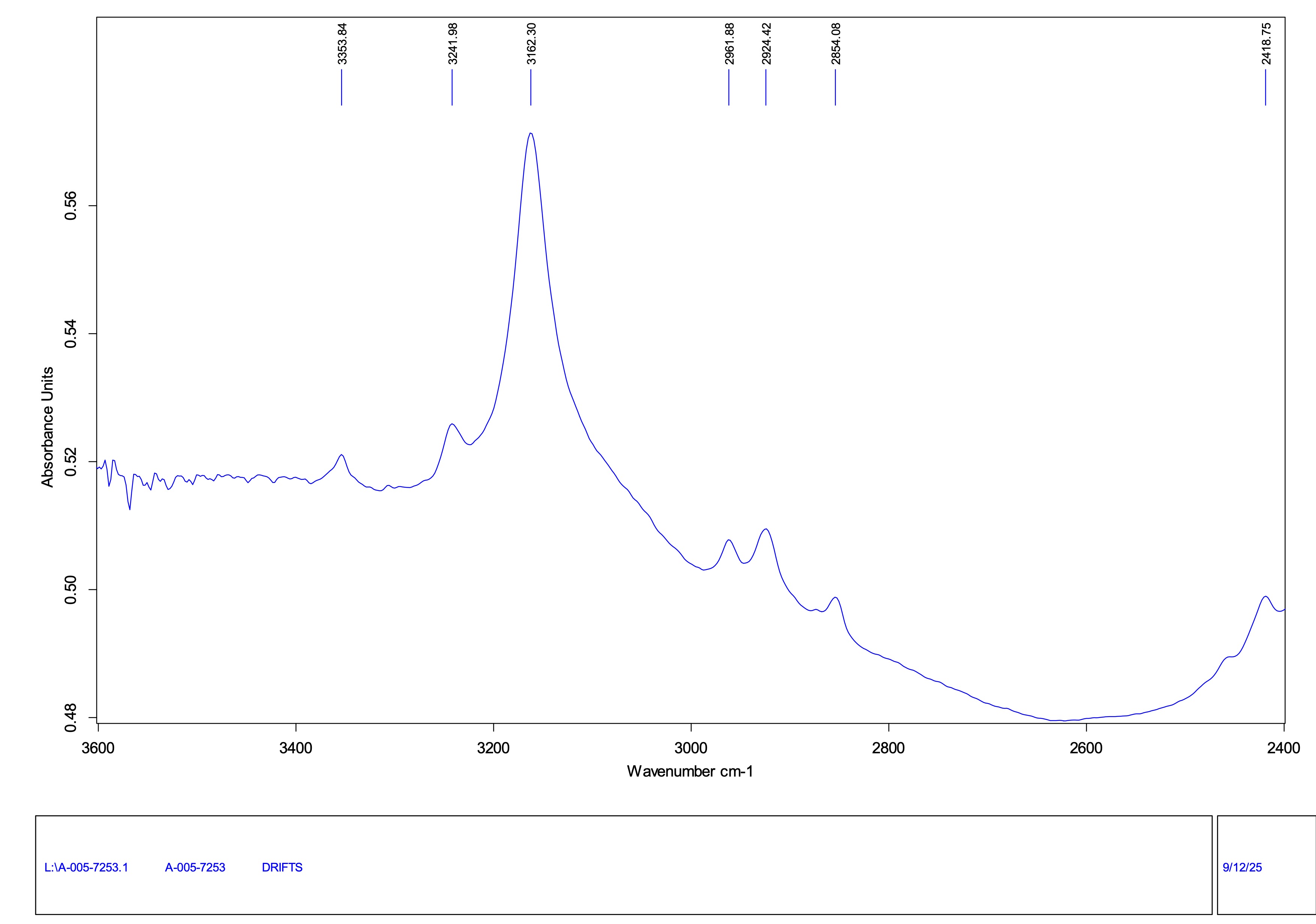

A. In many yellow (and orange) sapphires (particularly from Sri Lanka), the yellow/orange color is caused by a trapped hole color center. This produces a strong 3160 peak in the infrared spectrum, as shown above. Note: Peak labels are approximate only.

B. With heated yellow sapphires from Sri Lanka, the 3160 peak is destroyed by the treatment, and is generally replaced by a broad peak centered around 3000 (as above). This is believed to be due to internal diffusion of magnesium from exsolved particles into the host corundum.

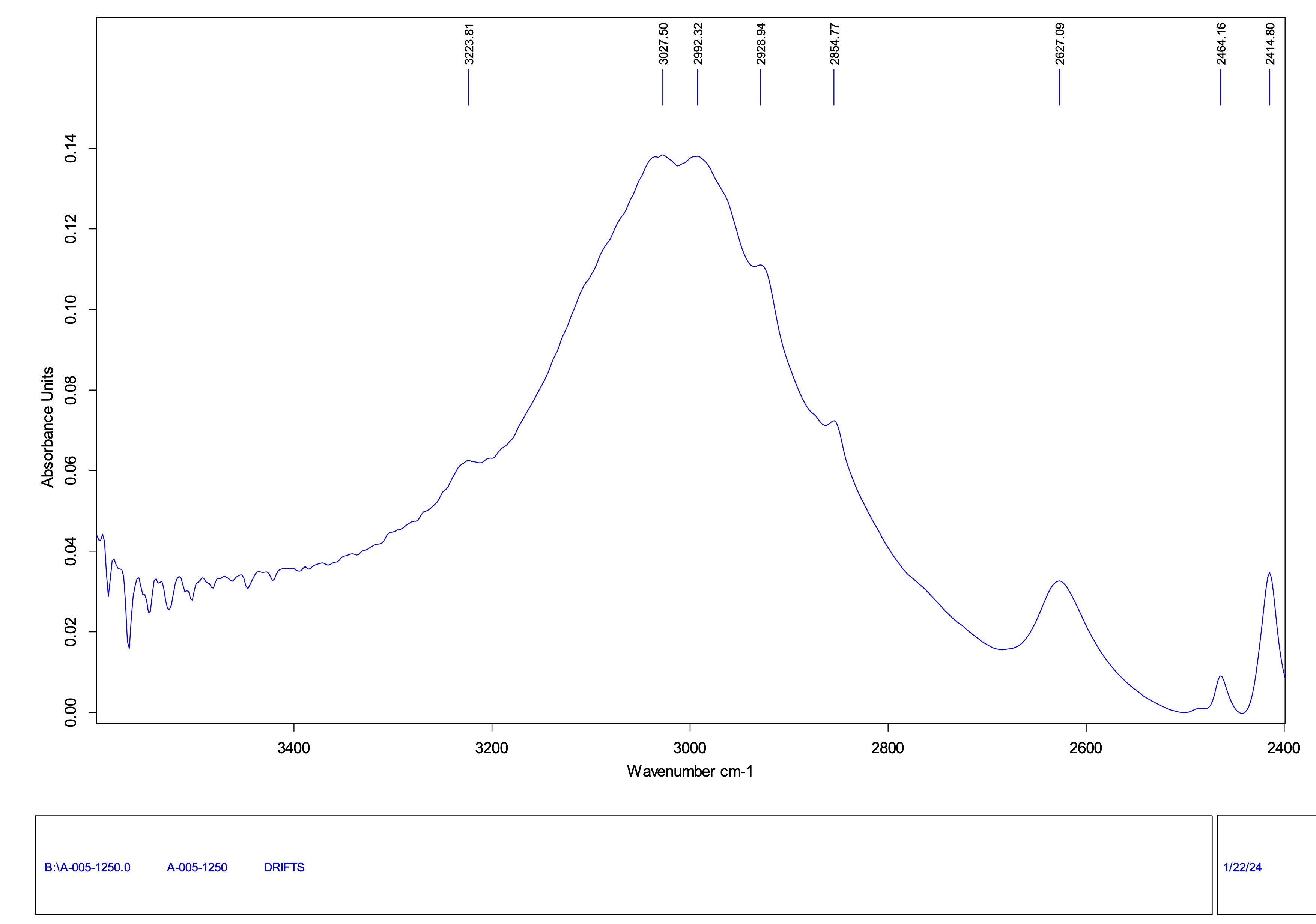

A. Low-grade corundum is often filled with glass to improve its clarity and/or color. This creates a band centered around 2700 in the FTIR. The band position will depend on the glass composition and the intensity of the band is dependent on the path length of the IR beam. Generally, with the DRIFTS method, this means that with heavily treated stones, such as Lead Glass-type Hybrids, the band will be the most prominent.

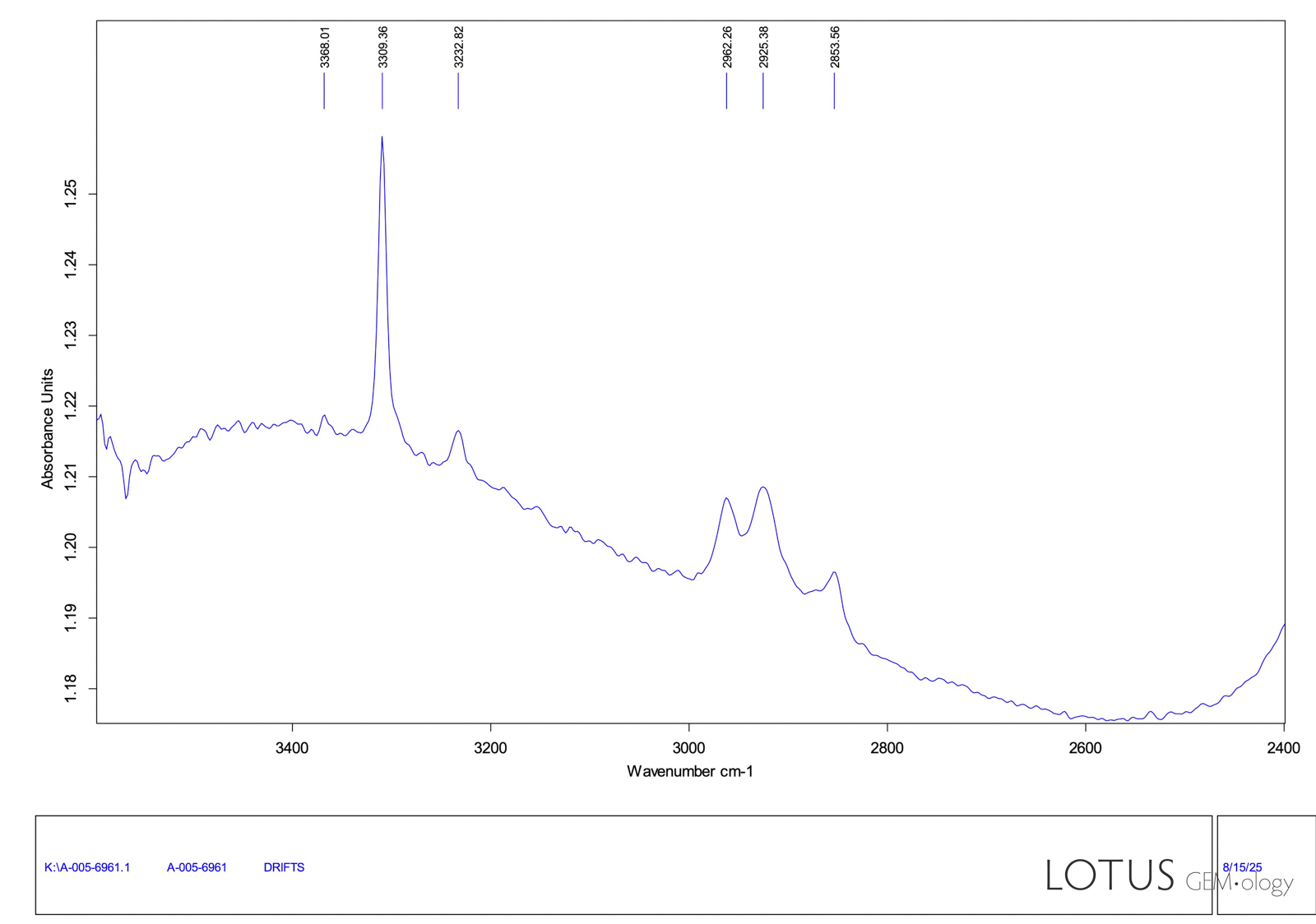

B. In contrast, “traditional” heated and even flux-heated stones generally only possess peaks from the 3309 series (3367, 3309, 3232, 3185) with particular importance placed on the 3232 peak. Note that the peaks at 2962, 2925 and 2853 are spectral artifacts related to surface grease that also overlap with the peaks of oil fillers.

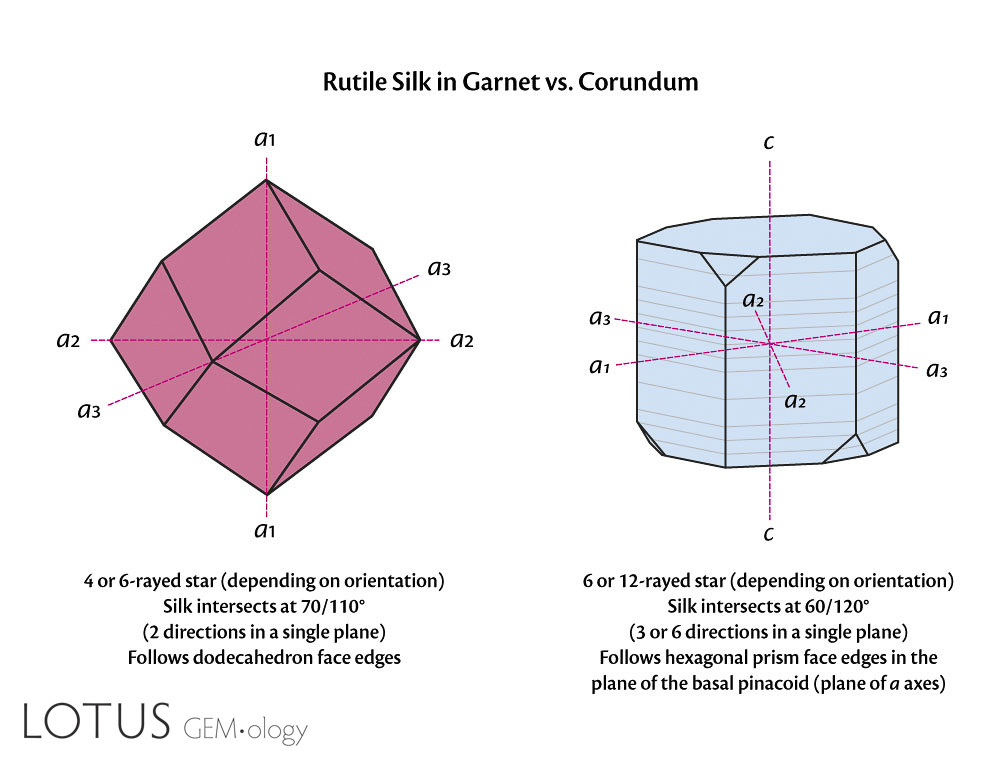

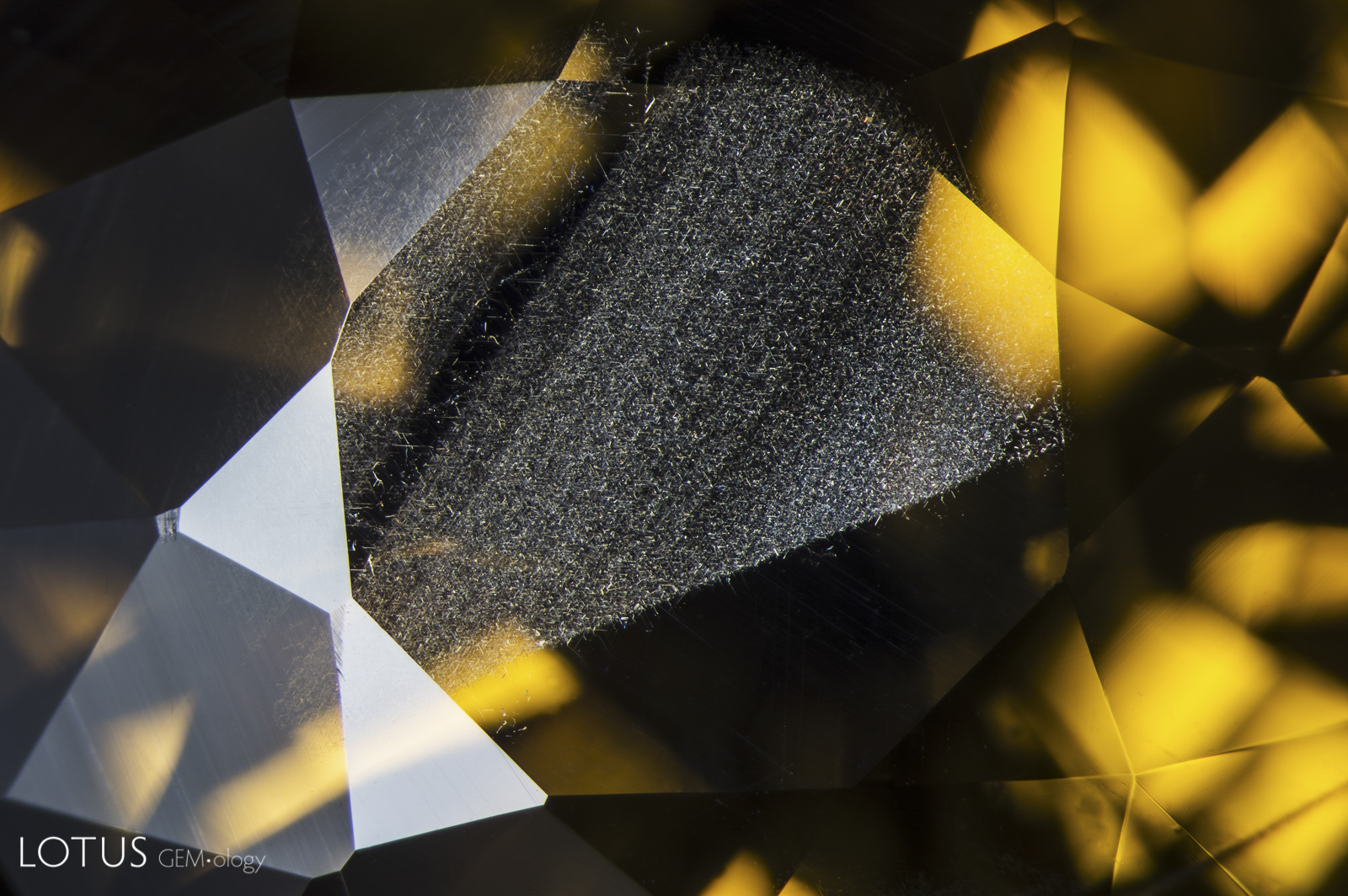

A. Rutile silk is composed of tiny crystals formed through a process called exsolution, the “unmixing” of a solid solution. The inclusions are influenced by the crystal structure of their host, so they intersect at different angles in different types of minerals. In garnet, rutile needles intersect at 70° and 110°, parallel to the edges of the rhombic dodecahedron and confined to two directions within a single plane, as illustrated by this spessartine garnet.

B. In contrast to garnet, rutile silk in corundum unmixes in three directions, parallel to the faces of the hexagonal prism in the plane of the basal pinacoid. Note how they intersect at angles of 60° and 120°, in three directions in the same plane.

C. The directions of silk exsolution in garnet versus corundum. In garnet, rutile exsolves parallel to the edges of the rhombic dodecahedron, with only two directions in the same plane, intersecting at 70/110°. In corundum, the silk unmixes in the basal plane and follows the edges of the hexagonal prism, with three directions in the same plane, intersecting at 60/120°. With 12-rayed stars, the there are six directions in the basal plane.

A. Hydrogen rich particle clouds create a rare trapiche-like appearance in this diamond. Specimen courtesy Asia Lounges.

B. When the same diamond is illuminated with a long wave UV torch, areas containing elevated hydrogen fluoresce bright green. Specimen courtesy Asia Lounges.

A. When a gem is heat treated after being faceted, facet damage due to the heating may be seen. Here, spall marks on the surface of this Mozambique ruby prove that it was heat-treated after cutting and polishing. Note that some of the spall marks have dark halos around them. The spall marks are caused by materials melting during the heat treatment, with that molten material solidifying into glass drops on the surfaces.

B. Spall marks on the surface of this Mozambique ruby prove that it was heat-treated after cutting and polishing.

C. This Mozambique ruby was subjected to heat treatment, producing spall marks on the surfaces. The evidence of heating remains on this indented natural because the polishing wheel did not reach into the depressed cavity.

D. The once-polished surface of this heat-treated sapphire was damaged by high-temperature heating, resulting in this pattern of flow marks on the surface.

A. Chalky fluorescence, visible in longwave ultraviolet illumination, unmasks filler in the fissures of this emerald. The low Fe content of Colombian emeralds often produces red fluorescence. When surface-reaching fissures are filled with oil or resin, the filler is unmasked by using a LW UV torch, where it fluoresces a chalky color in the fissures. This torch is an excellent tool for determining the extent of fissure-filling in emeralds and other gems.

B. Again, Chalky fluorescence, visible in longwave ultraviolet illumination, unmasks filler in the fissures of this Colombian emerald. Compare the levels of chalky fissures in this photo with that at left. This gem’s filler extent is rated FF-O₂, compared with the gem at left, which is FF-O1.

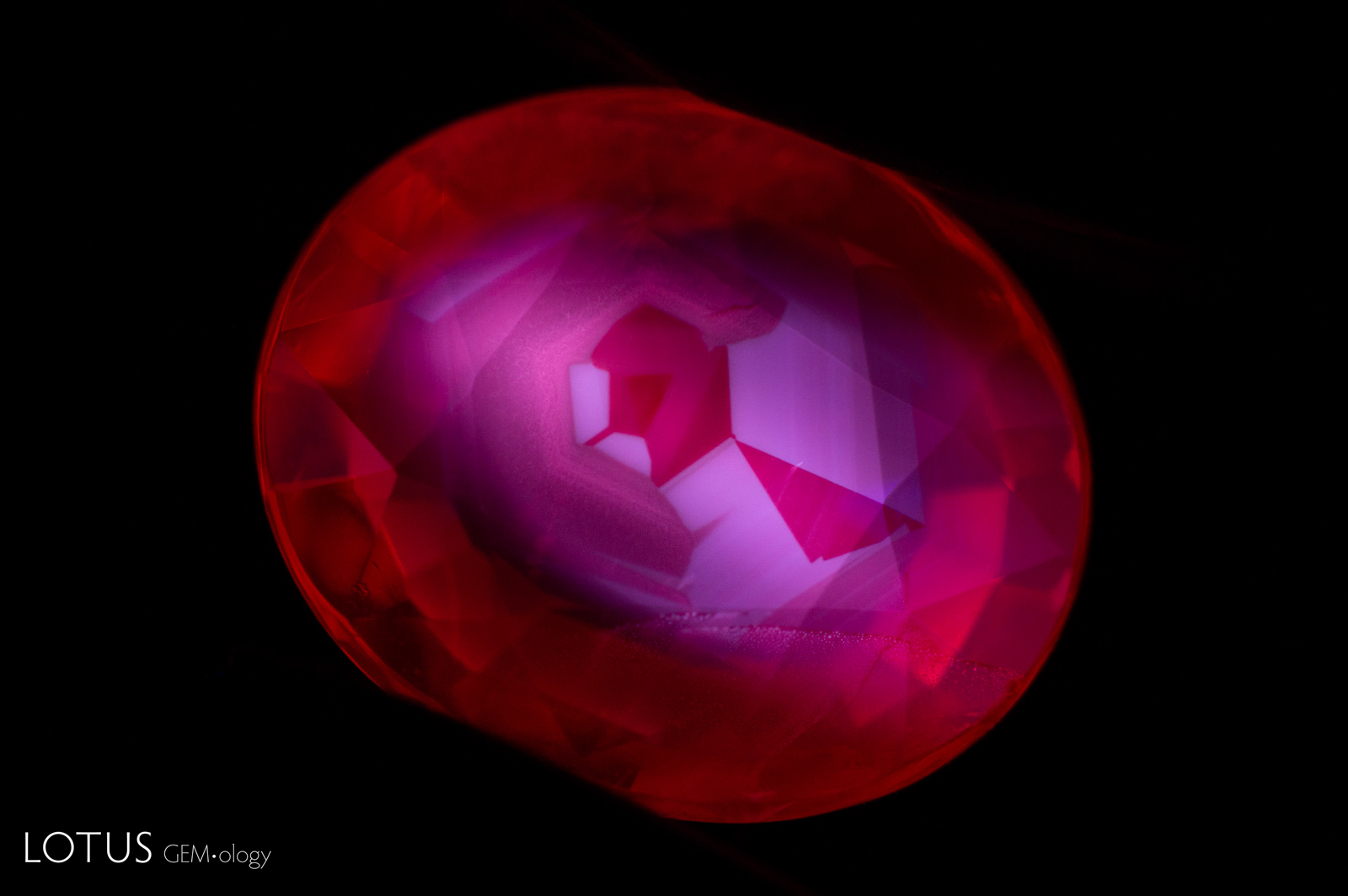

A. Prior to heat treatment, most Mong Hsu ruby crystals will feature a deep blue core surrounded by zoned clouds of fine exsolved diaspore particles; heat treatment will remove the blue core and other blue zoning. It also produces changes in the infrared spectrum.

B. Heat treatment of Mong Hsu rubies removes the blue core and damages the diaspore particles. When viewed in short wave ultraviolet light, such as that shown here, angular chalky zones can be seen, further confirming the fact that the stone has been heat treated.

C. After heat treatment of this Mong Hsu ruby, the blue core is gone. The angular zoned clouds of chalky fluorescence confirm that this gem has been subjected to heat treatment.

D. The angular blue zones and undamaged diaspore silk clouds confirm that this Mong Hsu ruby has not been heat treated.

A. The lack of contrast when a yellow sapphire is viewed using a yellowish incandescent light makes it difficult to see the growth zoning. This is particularly a problem when the gem is immersed in di-iodomethane, which is a yellow liquid. A yellow stone on a yellow light in a yellow liquid makes it nearly impossible to see growth zoning, as the above photo demonstrates.

B. The lack of contrast problem is solved by using a frosted blue filter between the gem and the light source. Now, the curved growth zoning of this yellow sapphire is easily seen, unmasking the gem as a Verneuil synthetic. This works for other colors of gems, too. The filter color should be the complimentary color of the gem color. Thus for a ruby, a green filter would be appropriate. This method was first discovered by Lotus Gemology’s Richard Hughes in the 1980s.

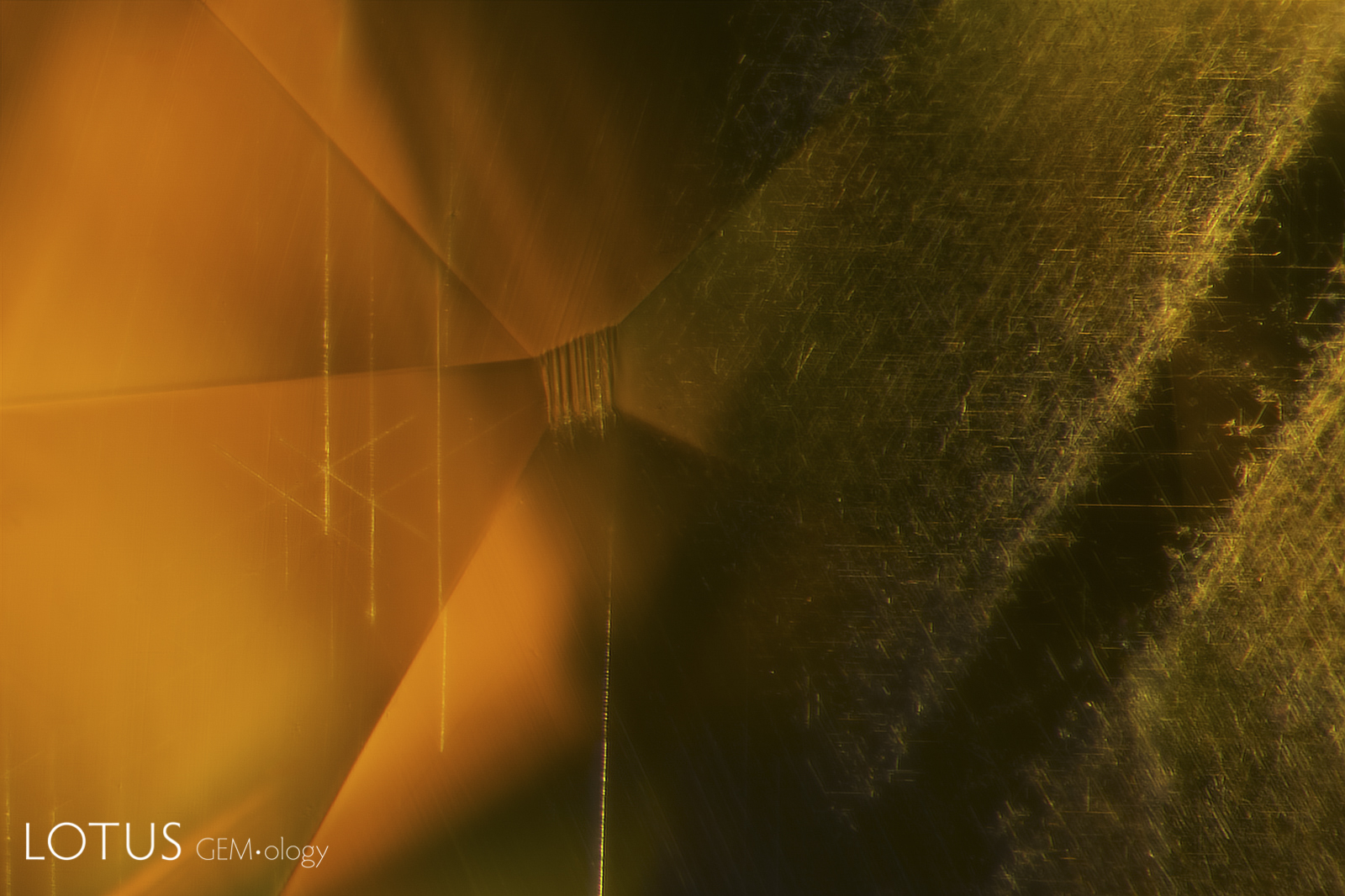

A. In yellow sapphires from Chanthaburi, Thailand, a thin layer of iron-rich silk is typically found in green layers on the skin of the crystal. After cutting, it is commonly seen just under the table and/or culet.

B. From this position, we can also see a series of fine Rose channels on the left, in addition to the Fe-rich silk on the right. Crossed polars will reveal that the Rose channels lie at the intersection of rhombohedral twin planes, which run oblique to the c-axis, unlike the Fe-rich silk, which unmixes in the basal plane parallel to the faces of the hexagonal prism.

C. The planes of Fe-rich silk in yellow sapphires from Chanthaburi, Thailand are typically just under the surfaces of the crystal faces and thus will be at or near the surfaces of faceted stones. When viewed on edge, the Fe-rich silk planes are typically a dark green color, as shown here.

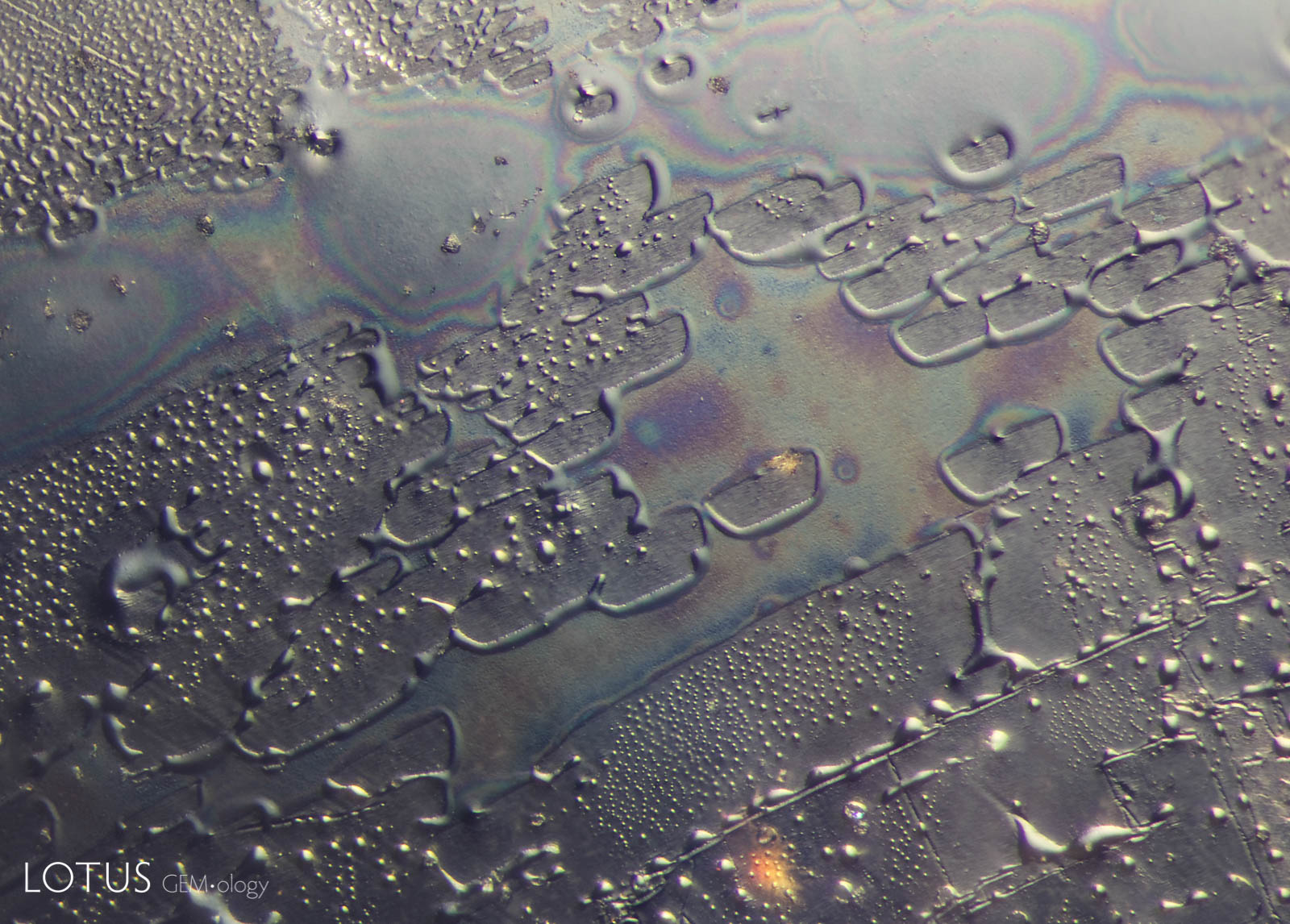

A. When a fissure heals in a crystal, it literally grows new layers within the opening, slowly sealing it shut. The remaining undigested fluids will remain behind in tiny negative crystals and the pattern of these cavities can reveal the underlying crystal structure of the host. In this photo, the rectangular healing pattern suggests that the fingerprint lies on or near a prism face (parallel to the c-axis).

B. In contrast, this healed fissure shows a hexagonal healing pattern, suggesting that it lies close to the plane of the basal pinacoid.

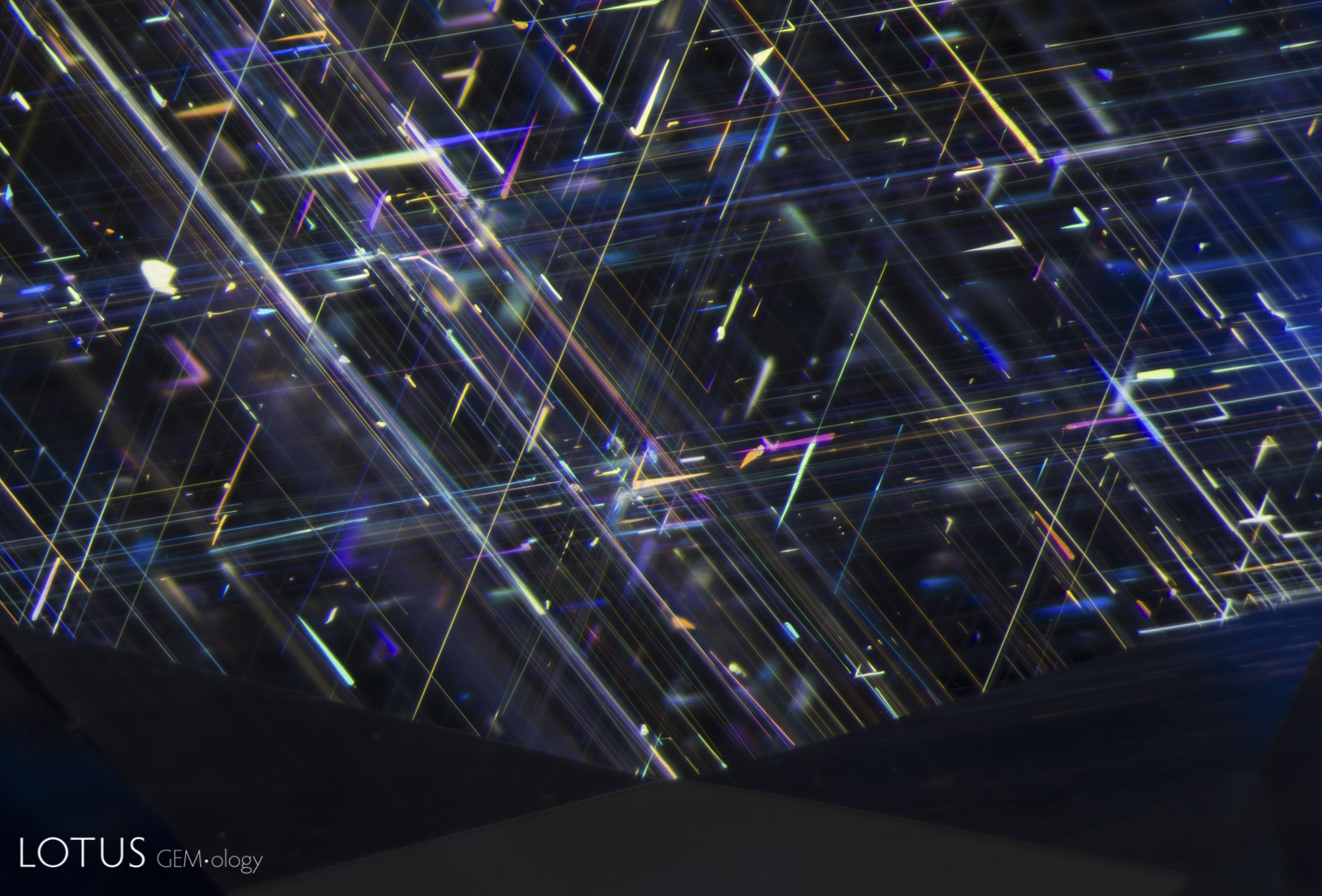

C. This healed fissure explodes with iridescent interference colors when lit from above. The rhomb-shaped healing pattern suggests that it formed oblique to the c-axis.

D. A prominent, intricate fingerprint pattern consisting of interconnected communication tubes extending from a mineral inclusion nucleus serves to confirm that this Sri Lankan spinel is natural. The form taken by the tubes reveals the isometric symmetry of the underlying spinel. Note the subtle differences in the healing pattern of this spinel relative to the previous corundum images.

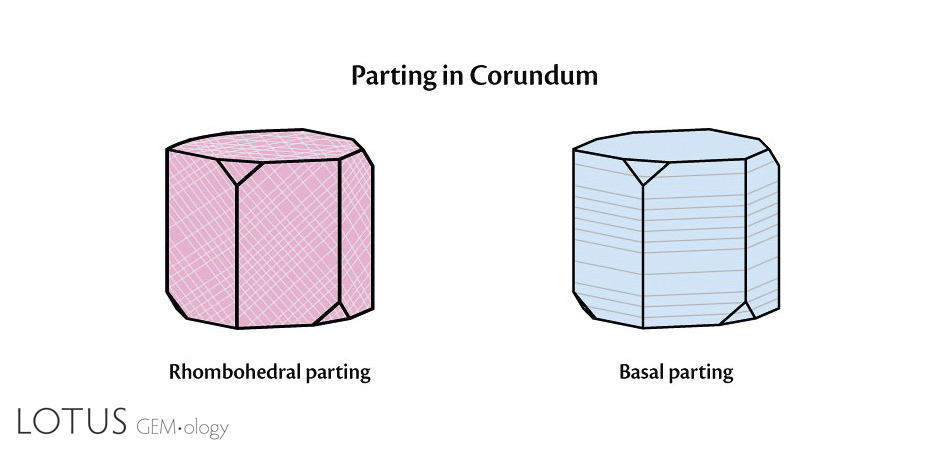

A. Basal parting on the back of a black star sapphire from Chanthaburi, Thailand. Exsolution of iron-rich inclusions in the basal plane produces mechanical weakness.

B. Basal parting seen on the back of a black star sapphire from Chanthaburi, Thailand. Note the step-like appearance. The two diagonal lines are rhombohedral parting planes. Basal parting in these stones is due to exsolution of hematite/ilmenite silk, which produces both the star effect and a lack adhesion.

C. The basal parting of black star sapphires often causes large pits on the back of certain stones. Traders may try to hide these pits with brown dopping varnish, as shown here.

D. This black star sapphire from Chanthaburi, Thailand has large pits on the base filled with brown dopping varnish. Long wave ultraviolet light shows the varnish fluoresces orange.

Note

The title graphic was inspired by master photomicrographer John Koivula, who demonstrated this technique of image mirroring to create aesthetic patterns at the International Gemmological Conference in Brazil in 1987.