This article traces the shift in Sino–Burmese gem exchange from a Ming-era emphasis on baoshi (寳石; rubies, sapphires, tourmalines and others) to the Qing embrace of Burmese jade, or fei cui (翡翠). Using Yunnan-centered sources, it argues that the term fei cui was first applied to Burmese jade in 1719 (Ni Tui), marking a conceptual turn that paralleled a market one: by the late 18th century, fei cui trade through Tengyue/Dali expanded rapidly, values soared, and top fei cui surpassed Xinjiang yu (nephrite) in price. Court taste—especially under Qianlong—accelerated demand, reorienting extraction and commerce in northern Burma. The study highlights evolving terminology, monopolies over ruby/sapphire, and growing jade-working industries, concluding that Chinese consumer preference was the primary external force shaping Burmese gem mining and exports from the Yuan–Ming through the Qing and into the modern era.

A base [fei cui] stone wastes so much money; it is indeed a monster thing (wuyao 物妖).

—Xu Zhongyuan, Sanyi bitan 三異筆談 (1920)

The price [of fei cui jade] far exceeds the genuine jade (zhenyu 真玉) [from Xinjiang]!

—Ji Yun, Yuewei caotang biji 閱微草堂筆記 (2001)

As a preliminary inquiry into an understudied but significant topic in Sino-Southeast Asian economic history, this essay has two goals. First, it intends to clarify some issues surrounding the spread of Burmese jade (fei cui; 翡翠) to China.1 With the increasing consumer interest in Burmese gems (jade in particular) since China’s economic reforms in 1978, academic interest in the history of Burmese jade exports to China has also surged. Two issues have been hotly debated: when did Burmese jade spread to China? And when did the Chinese first apply the term fei cui to Burmese jade? The first issue will be dealt with in a separate paper in greater detail (mentioned in passing below).2 As for the second issue, the earliest use of the term fei cui, this paper points out that all the available studies have tackled the problem outside the Yunnan context, thus making it difficult to reach a correct conclusion. Carefully sifting through the many hitherto ignored Chinese sources and examining the fei cui issue within the Yunnan context, one is on safe ground to say that in 1719 the term fei cui was first applied to Burmese jade.

Second, a better understanding of the gem trade during the Qing period requires comparison with that of the Ming dynasty. For half a century, the scholarly inclination to lump together Ming and Qing trade has hidden critical differences between the two eras.3 Careful comparison of the two eras reveals that an important change took place: while the baoshi (including rubies, sapphires, and tourmaline, but excluding jade, according to the Chinese usage)4 dominated the gem trade during the Ming, during the Qing, especially from the eighteenth century on, fei cui (as a type yu 玉) started to overtake the baoshi. This change can be traced to shifting fashions in the Chinese court, for often it was the taste of the Chinese emperor and his consorts that dictated the mining and trading of gems in northern Burma.

This research concludes with the argument that China was (and still primarily is) a major driving force behind the whole gem business, particularly jade mining and trade. In other words, one can say that from its inception through the first half of the twentieth-century trade in gems was largely a “Chinese business” as it was instigated by Chinese demand. Using the example of the Qing-Burmese gem trade, I highlight China as an external stimulus on the development of Southeast Asian history.

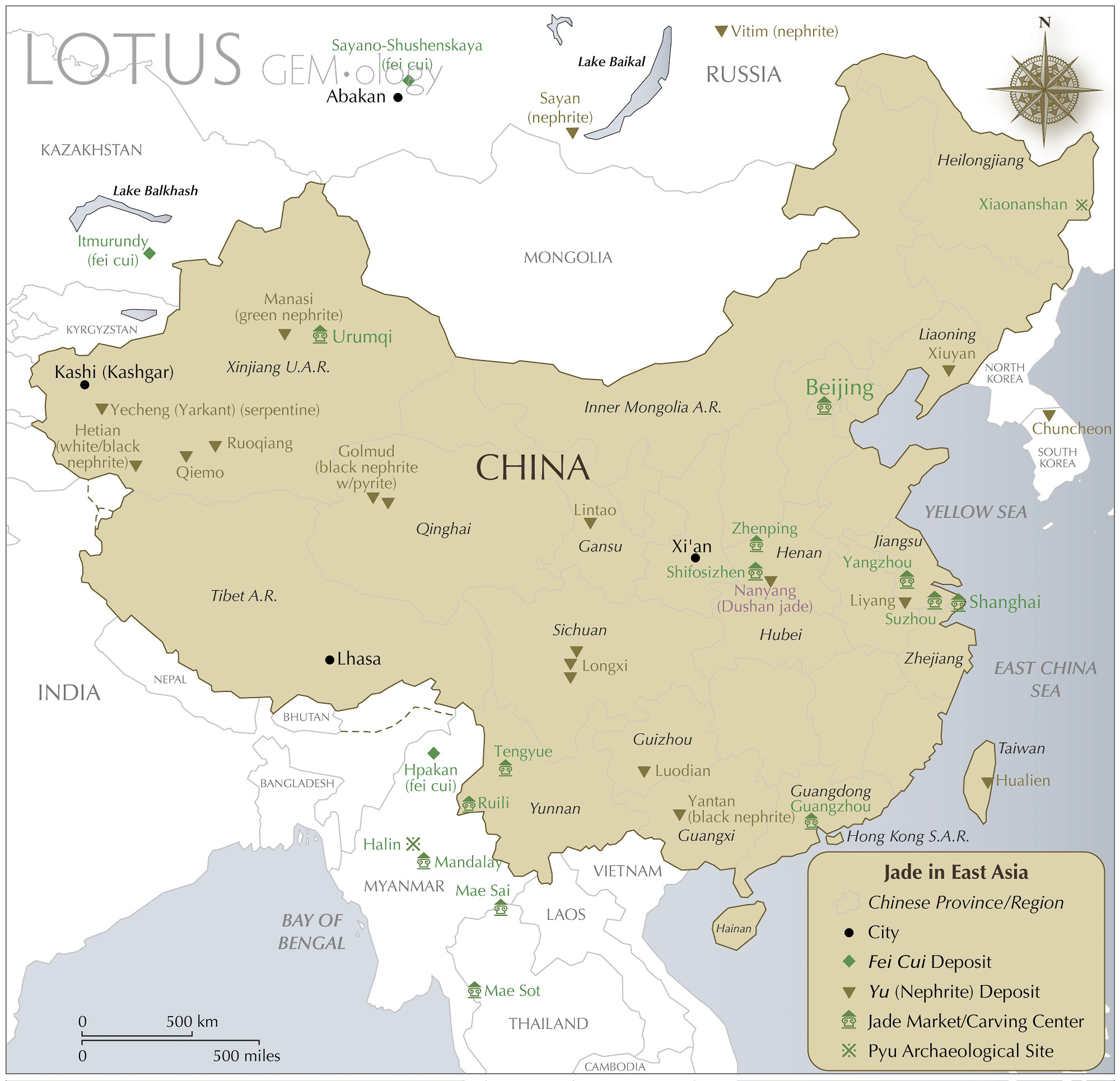

Map of Southeast Asia, showing the fei cui mines in upper Myanmar at Hpakan. Fei cui has been found in archaeological digs at the ancient Pyu site at Halin. Note also the proximitry between Hpakan and the Yunnan (China) city of Tengyue. Map: Richard W. Hughes.

Map of Southeast Asia, showing the fei cui mines in upper Myanmar at Hpakan. Fei cui has been found in archaeological digs at the ancient Pyu site at Halin. Note also the proximitry between Hpakan and the Yunnan (China) city of Tengyue. Map: Richard W. Hughes.

Burmese Gems and Yuan-Ming China

Although Burmese jade and rubies were discovered at some Pyu sites (from the third to the eighth centuries), gemstones from Burma did not appear in China until the late thirteenth century, with the invasion of Burma by the Mongols, who had introduced gemstones from Western Asia to China not long before. It is likely that the growing demand for gems in China gave rise to the relatively large-scale mining of Burmese gemstones. Although Chinese sources still do not specify the gems, they probably included jade, rubies, and amber. In other words, it was the Mongols who jump-started gem mining in Upper Burma and the gem trade with China.

Despite the distaste of the (Han) rulers of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) toward Mongol culture, they not only inherited the Mongol craze for gemstones, but dramatically popularized them across China. Particularly from the mid-fifteenth century, a “gem fever” (more for baoshi than for jade) started by Wan Guifei, the favorite consort of the Ming emperor Xianzong (r. 1465–1487), spread quickly throughout the country. This intensified the mining and export of Burmese gems and precipitated the emergence of two Shan principalities in Upper Burma—Mongmit and Mohnyin—which controlled gem sources and benefited from the trade.5 Again, China acted as a primary mover for the Asian gem trade in general and the Burmese gem trade in particular.

An end to Ming court procurement of gems in 1599 in Yunnan cooled but did not extinguish the gem fever. As late as 1639, when the famous Ming traveler Xu Xiake was in western Yunnan, he witnessed Burmese gems on sale in the market and local gem traders being harassed by gem searchers sent by local officials, which suggests that gems were still prized and sought by the Chinese. For example, in Dali, he saw gem merchants from Yongchang (modern Baoshan) selling “baoshi, amber, and jade” from Burma, while in Tengyue (modern Tengchong) he himself was offered jade.6 The Chinese fascination with baoshi in particular did not end with the dynastic transition from the Ming to the Qing in 1644.

The Transition of the Gem Trade (c. 1644–1719)

The earliest account of the Qing-Burmese gem trade was written by Liu Kun in 1680.

Merchants collect the stones and return to the frontier passes. Those rubble-shaped ones are called “rough stones” [huang shi 荒石]. The workmen in Tengyue grind them with shellac [zigeng 紫梗] and smooth them with small stones [baosha 寶砂], and then they start to shine [baoguang 寶光].7 The red-[colored] ones are the best, such as “rose-water” [meigui shui 玫瑰水], “pigeon-blood” [gezi xie 鴿子血], and “garnet color” [shiliu hong 石榴紅]. All these are good ones, whereas those called “old red” [lao hong 老紅] are valueless. The blue ones are called yaqut [yaqing 鴿青], the white ones cat’s-eye [maoeryan 貓兒眼], the green ones zumurrud [zumulü 祖母 綠].8 But only the extremely shiny ones are excellent pieces. Those as big as peas are called “hat top” [maoding 帽頂], those as big as soybeans and mung beans are called “precious stones” [baoshi 寳石], while the smallest ones are called “ghost eyelash” [gui jieyan 鬼睫眼].9

This account reveals precious information on the classification of gems and the gem trade in the late seventeenth century. Far more effectively than the descriptions of Song Yingxing (1587–1666) and Gu Yingtai (1620–90), Liu Kun contributes to the terminology of gemstones in general and of Burmese rubies and sapphires in particular.10 For example, he uses, for the first time, gezi xie and gui jieyan to describe gemstones, and applies meigui (hong) and shiliu (shui) to Burmese rubies and sapphires, illustrating that Chinese knowledge of these gems had deepened. Indeed, either the Chinese or, more possibly, the Arabs invented the term “pigeon’s blood” and the Burmese borrowed this term (kuiswe) to refer to the best kind of ruby.11

During the early Qing, the gems from Burma desired by the Chinese were still dominantly baoshi (as during the Ming times), not jade (yu). This is seen from the fact that Liu Kun writes with elaborate detail on baoshi, despite the fact that his zumulü may refer to jade. Three other accounts written in or concerning Yunnan between 1687 and 1694 reinforce the view that the Chinese were still primarily fascinated with baoshi, not jade. All of them mention Burmese baoshi, and two have relatively detailed descriptions, while only one mentions jade (biyu 碧玉).12

The Chinese probably could not purchase the best baoshi, including rubies and sapphires, as the Burmese king had monopolized the mines since the late sixteenth century.13 Many Chinese sources of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, including the one by Liu Kun, attest to this.14 For example, Liu Wenzheng stated in 1625, “Now it is up to the barbarians (the Burman and the Shan) to provide [baoshi], whereas in the past [the Chinese] could choose at will and set the price. Thus the prices are getting increasingly high, while the good ones are harder to obtain.”15

Xu Jiong, who was sent to Yunnan as an inspector, wrote around 1688 on Burmese baoshi. He first quotes Liu Wenzheng’s observation above, then provides his own comments.

Also, in the barbarian land there is much poison, and on the way the bandits are rampant. [Baoshi traders] who take shortcuts to avoid custom duties suffer heavily [from these dangers]. I hear that in recent years the barbarians guard baoshi even tighter; those who take [baoshi] out of [Burma] will be immediately executed. There are big baoshi, [but they have to be] broken into smaller pieces and then smuggled out [to China]. Even the small ones are not cheap! At present these [gem] stones in the capital (Beijing) are from Yunnan, but in Yunnan they are not as good as those in the capital (Beijing). This is because [in Yunnan] females do not use them as decorations, and the Luoluo [Yi people] favor black color. Thus beautiful stones mostly reach the capital while it is difficult to obtain locally [within Yunnan].16

The last sentences of this passage suggest huge demand for Burmese gems in the capital Beijing, while the demand in Yunnan was small.

Unlike Burmese jade which was solely exported to China up to the twentieth century, rubies, sapphires, and other gemstones were in demand among Chinese and Burmese, as well as among Indians and Europeans. By the end of the sixteenth century, the Chinese were the largest buyers, but after the Burmese court took control of the mines the quantities and quality of baoshi exported to China must have dwindled.

The Debut of Fei Cui (c. 1719–1763)

Up to the mid-eighteenth century, it appears, baoshi still dominated the Qing-Burmese trade. Nonetheless, Burmese jade was gaining momentum. As Burmese jade increased in popularity, soon to replace baoshi as the primary export to China, the term fei cui was introduced.

The transition from baoshi to fei cui can be observed in the writings of the historian Ni Tui, who arrived in Yunnan in 1715. In his 1719 work, Dian xiao ji, he wrote a lengthy passage entitled “Baoshi,” which not only includes important information on the historical development of baoshi in China and baoshi trade during the Ming times, but also lists various types of Burmese baoshi.

The green ones: luzi 瓐子 and zumulü; the blue ones: soft blue [ruanlan 軟 藍] and fei cui; the white ones: diamond [jin gang 金剛], and tan yangjing 賧羊精 [literally “(color of) goat semen”]; the yellow ones: cat’s eyes 貓 睛, and jiuhuang fen 酒黃粉 [literally “(color of) powder of yellow Chinese chives”]; the red ones: tourmaline or garnet [biyaxi 比牙洗]; and so on, which cannot be all enumerated.17 It is unknown whether they are from the same mine or not.18

This is a valuable account. First, Ni Tui provides new classifications of baoshi, including tan yangjing, which had never before appeared in Chinese records, while jin’gang and biyaxi are applied to Burmese baoshi for the first time. Biyaxi is a loan word from the Arabic bijādī, with its Persian form being beejād.19 The Chinese transliteration of bijādī is various, with the earliest one being bizheda 避者達 in Tao Zongyi’s 陶宗儀 Nancun Cuogeng Lu 南村輟耕錄, written in 1366.20 The Tengyue prefect Tu Shulian provides the most detailed description on bixiaxi:

Besides baoshi there is bixiaxi. It has five colors, with the crimson and clear [toushui 透水] ones being the best, and purple, yellow, green, and moon white colors being inferior, while the worst ones are white and black colors. They are also produced in Mongmit [near Mogok], perhaps belonging to the baoshi type.21

Second and more important, Ni Tui used the term fei cui, probably for the first time, to refer to Burmese jade, albeit lumped under the rubric of baoshi. This creative use of the word fei cui was influential, as it would soon be employed to refer to Burmese jade exclusively. Looking at the Chinese terminology for Burmese jade from the mid-Ming times, one realizes that the Chinese, the Yunnanese in particular, had been trying to find a suitable term for Burmese jade for a long time (see table 1).22

| Period | Year | Gems / Terms |

|---|---|---|

| Ming Dynasty | ||

| 1455 | Hupo 琥珀 (produce of Mohnyin/Mengyang 孟养) | |

| c. 1475 | Yudai 玉帶, Lüyu 綠玉, Zumulü 祖母綠 | |

| 1488 | Yushi 玉石 (presented by Yixi or Mohnyin natives 迤西夷人) | |

| 1510 | Hupo 琥珀, bitian 碧瑱 (produce of Mohnyin) | |

| 1583 | Baoshi 寳石, cuisheng wenshi 催生文石, hupo 琥珀, baiyu 白玉, biyu 碧玉; Lüyu 綠玉, heiyu 黑玉 | |

| 1619 | Yunnan biyu 雲南碧玉 | |

| 1621 | Baoshi 寳石, baosha 寳砂, cuisheng shi 催生石, shuijing 水晶, lüyu 綠玉, moyu 墨玉, bitian 碧瑱,biyu 碧玉 | |

| 1632 | Baoshi 寳石, hupo 琥珀, lüyu 綠玉, heiyu 黑玉, cuisheng shi 催生石, Moyu 墨玉,biyu 碧玉 | |

| 1639 | Baoshi 寳石, hupo 琥珀, cuisheng shi 翠生石, biyu 碧玉 | |

| 1611–71 | Yunnan bi 雲南碧 | |

| Qing Dynasty | ||

| 1680 | Hongzhu 紅珠/baoshi 寳石: meigui shui 玫瑰水, gezi xue 鴿子血, shiliu hong 石榴紅, yaqing 鴉青, maoeryan 貓兒眼; Zumulü 祖母綠, maoding 帽頂, baoshi 寳石, guijieyan 鬼睫眼 | |

| 1687–88 | Baoshi 寳石 | |

| 1688 | Hupo 琥珀, biyu 碧玉, zhenbao 珍寶 | |

| 1691 | Caiyu 菜玉,moyu 墨玉,cuisheng shi 催生石 | |

| 1694 | Hupo 琥珀, biyu 碧玉, zhenbao 珍寳, baoshi 寳石 | |

| 1702 | Hupo 琥珀, shuijing 水晶, caiyu 菜玉, moyu 墨玉, cuisheng shi 催生石; baosha 寳沙, baoshi 寳石 | |

| 1719 | Baoshi 寳石: luzi 瓐子, zumulü 祖母綠, ruanlan 軟藍, fei cui 翡翠, jingang 金剛; Tan yangjing 賧羊精, maojing 貓睛, jiuhuang fen 酒黃粉, biyaxi 比牙洗 | |

| 1733 | Yongchang biyu 永昌碧玉 | |

| 1736 | Hupo 琥珀, shuijing 水晶,caiyu 菜玉, moyu 墨玉, baosha 寳砂; baosha 寳砂, haijinsha 海金砂, baoshi 寳石, cuishengshi 催生石, ziyingshi 紫英石 | |

| 1741–53 | Baoshi 寳石: meigui 玫瑰, yinghong 映紅, yingqing 映青 | |

| c. 1763 | Baoshi 寳石, hupo 琥珀, fei cui 翡翠, manao 瑪瑙 | |

| 1764 | Yunnan yu 雲南玉 | |

| 1769 | Bixiya 碧石先砑 | |

| c. 1769 | Yushi 玉石, baoshi 寳石, biyaxi 碧牙西 | |

| 1769 | Hupo 琥珀, baoshi 寳石 | |

| 1769 | Bixiaxi 碧霞璽 | |

| 1771 | Yunnan yu 雲南玉 | |

| 1771 | Fei cui 翡翠 | |

| 1772 | Yunnan yu 雲南玉 | |

| 1772 | Fei cui 翡翠 | |

| 1772–82 | Dianyu 滇玉, baoshi 寳石, bi(xia)sui 碧(霞)髓, fei cui shi 翡翠石, cuisheng shi 催升石 | |

| 1777 | Bixia? 碧霞王ム, fei cui yu 翡翠玉, yushi 玉石 | |

| 1777 | Dianyu 滇玉 | |

| 1779 | Fei cui 翡翠 | |

| 1780 | Fei cui 翡翠 | |

| 1782–95 | Yu 玉, baoshi 寳石 | |

| 1790 | Baoshi 寶石, bixia 碧霞, yinhong 印紅, zhubao 珠寶, baiyu 白玉, cuiyu 翠玉, moyu 墨玉, hupo 琥珀, bixiaxi 碧霞璽, baosha 寶沙 | |

| c. 1790 | Baoshi 寳石: yinghong 映紅, yinglan 映藍, bixiaxi 碧霞洗 | |

| 1793 | Fei cui yu 翡翠玉,lüsongshi 綠松石,biyaxi 碧鴉犀 | |

| 1795 | Fei cui 翡翠; yu 玉, fei cui 翡翠, baiyu 白玉,cuiyu 翠玉, heiyu 黑玉, baoshi 寳石; bixiaxi(pi) 碧霞璽(玭), bixi 碧洗, kulani 苦剌泥, bitian 碧瑱, yinhong 印红, haozhu ya 豪猪牙,ruanyu 软玉 | |

| 1802 | Fei cui 翡翠 | |

| 1804 | Fei cui yu 翡翠玉 | |

| 1816 | Fei cui yu 翡翠玉 | |

| 1827 | Boashi 寳石, fei cui 翡翠, bixi 碧璽, Yunnan yu 雲南玉 | |

| 1839 | fei cui 翡翠 | |

| 1848 | Yushi 玉石, hupo 琥珀, baoshi 寳石, lihong 瓅玒 | |

| c.1852 | Hupo 琥珀, baoyu 寳玉 | |

| mid-1900s | Fei cui 翡翠 | |

| mid-1900s | Feicui 翡翠, bixi 碧璽 | |

| mid-1900s | Feicui 翡翠 | |

| 1862 | Feicui 翡翠 | |

| 1864 | Cuishi 翠石,fei cui shi 翡翠石 | |

| 1871 | Yu 玉, ruanzan 軟瓚, baoshi 寳石, bixi 珌璽, fei cui 翡翠, cuiyu 翠玉 | |

| 1875 | Yushi 玉石, hong baoshi 紅寶石, yaqing 鴉青 | |

| 1875 | Yushi 玉石 | |

| 1879 | Yushi 玉石 | |

| 1886 | Yu 玉, hupo 琥珀, baoshi 寶石, bixia(xi) 碧霞(犀) | |

| 1887 | Jade category 玉属: bixia baoshi 碧霞寶石, yinhong baoshi 印紅寶石, Hongla baoshi 紅剌寶石, yushi 玉石, hupo 琥珀, manao 瑪瑙, shanhu 珊瑚 | |

| 1890 | Biyu 碧玉, Yunnan yu 雲南玉, fei cui 翡翠; fei cui 翡翠, yushi 玉石,baoshi 寶石, maojing shi 貓睛石, hupo 琥珀 | |

| 1890s | Yushi 玉石, baoshi 寳石, cuiyu 翠玉 | |

The History of Burmese Jade in China

The history of Burmese jade in China can be traced according to the evidence presented in Table 1, for which the abundant information on Burmese baoshi for the Ming period has been omitted in order to highlight the Burmese jade. Burmese jade possibly started to reach China in the late thirteenth century, but the “gem fever” of the mid-Ming gradually lent it visibility and importance. For example, prior to 1475, jade from Burma was not recorded, and the 1455 gazetteer of Yunnan mentions only that Mohnyin (Mengyang) produced amber (which had entered Yunnan centuries before). Around 1475 appeared hard written evidence showing that Burmese jade was prized and sought (and even sent to Vietnam as gifts) by a Ming eunuch. No doubt, some amount of Burmese jade had arrived in Beijing and other places in China with large quantities of baoshi. Interestingly, it was already called yu 玉, lüyu 綠玉, and zumulü 祖母綠 by the Chinese, emphasizing, correctly, the green color of the Burmese jade, as the word lü 綠 indicates. An account of 1488 even records that people from Mohnyin presented jade (yushi 玉石) to the Ming court. The 1510 gazetteer of Yunnan accordingly updated the produce of Mohnyin by adding green jade (bitian 碧瑱), referring to the Burmese jade and stressing its green color (bi 碧). The firsthand account of 1583 suggests that western Yunnan and Upper Burma (particularly Mohnyin) produced many kinds of jade: cuisheng wenshi 催生文石, baiyu 白玉, biyu 碧玉, lüyu 綠玉, heiyu 黑玉. Actually, they should have all come from Mohnyin.23 The 1621 account states:

Foreign-produced amber, crystal, green jade (biyu), Gula (Assamese) brocade, Western Ocean cloth, and drugs such as asafoetida and opium are gathered and distributed [by Yunnan merchants], and walk to the four directions without legs.24

The green jade no doubt came from Mohnyin. This suggests that jade from Upper Burma circulated in China to a certain degree, and the earliest archaeological find of jade in fact testifies to this circulation.25 One hastens to add that, comparatively speaking, the amount of Burmese jade in China was still small (vis-à-vis the much larger quantities of baoshi), hence it is not surprising that archaeological finds are still very rare.

However, from around 1475 to the end of the Ming dynasty (and later), the Chinese had been searching for a better name for Burmese jade. During this relatively long period (about 170 years), about ten different names (yu 玉, lüyu 綠玉, zumulü 祖母綠, bitian 碧瑱, yushi 玉石, cuisheng wenshi 催生文石, cuisheng shi 催生石, cuisheng shi 翠生石, biyu 碧玉, heiyu 黑玉, moyu 墨玉, and even possibly baiyu 白玉 [for non-green color Burmese jade]) were used. Even Xu Xiake himself used two names (cuisheng shi 翠生石 and biyu) to refer to the same thing, showing the fluidity of the Chinese terminology for Burmese jade.

Despite these various terms, most accounts emphasize the green color or shade, indicated in words such as lü, cui, bi, and even mo and hei. The word cui 催 is apparently a mistake for cui 翠 (which means 'green,' greener than ordinary lü), as Xie Zhaozhe, using the term cuisheng shi 催生石 in 1621, explained that the gem had “green color with white spots” (secui er jianbai 色翠而間白).26 Xu Xiake makes clear that people in Yunnan favored the pure cui ones (chuncui zhe 纯翠者). This demonstrates that the Yunnanese had, from the very beginning, noticed the special green color in Burmese jade and applied the word cui to it. This usage of the word cui led eventually to the term fei cui for the Burmese jade in the eighteenth century, starting from Ni Tui in 1719.

Burmese jade was not known to the Qing court until 1733, when the Yunnan governor Zhang Yunsui presented a piece of “Yongchang green jade” (Yongchang biyu 永昌碧玉) to the Qianlong emperor. The possible origins of the Burmese word for jadeite, kyok’ cim’ (literally “green stone”) are worth examining. Such a popular usage in modern Burmese actually has a relatively short history. It first appeared in the early seventeenth century, around 1637–1638, and probably did not become popular until the nineteenth century.27 Prior to the seventeenth century, at least in the Burmese chronicles, mra or mra kyok’ were used for fei cui (or green-colored gems).28 This Burmese usage is corroborated more by the Burmese-Chinese dictionaries compiled by the Chinese for official translation by the sixteenth century (and updated in the early eighteenth century). In these dictionaries, the Burmese word mra was transliterated as 比呀 (biya) or 麥剌 (maila) and translated as “玉 (yu),” while mra kyok’ was transliterated as 哶繳 (miejiao), 麥剌繳 (mailajiao), or 麥賴繳 (mailaijiao) and translated as “玉石 (yushi).”29 In view of the long emphasis by Chinese from the late fifteenth through the early seventeenth century on the “green” (lü, cui, and bi, etc.) color or shade of the Burmese jade, and the appearance of the Burmese word kyok’ cim’ in 1637–1638, one may speculate that the coining of this Burmese new word was due to Chinese influence. This should not be surprising, as the terminology and classification of Burmese jade have been dictated by the Chinese. Moreover, up to the early eighteenth century, the term fei cui had not entered the official Chinese usage, and it still took more time to popularize it.

The Triumph of Fei Cui (c. 1763–c. 1800)

From the 1760s on, fei cui starts to appear more frequently in Chinese records. Indeed, Burmese jade, quite literally, began to show its true colors to the Chinese people.

Zhang Yong, in his work Yunnan Fengtu Ji (c. 1736), described the bustling market in Dali, western Yunnan:

Precious and exotic goods are bought and sold, such as baoshi, amber, fei cui . . . Burmese tin, Burmese brocade. . . . Entering the market, [one sees] all kinds of precious and exotic things, goods and people are as many as ten thousand everyday.30

This was indeed a huge market for Burmese commodities, especially gems. Though it seems that baoshi still dominated as it is listed first, fei cui (third on the list) clearly refers to Burmese fei cui. It must be that the Yunnanese had adopted Ni Tui’s word fei cui, which had first appeared in 1719. From 1764 to 1772, in Chinese records, including Qing palace archives, Burmese fei cui is much more frequently mentioned than baoshi under the names Yunnan yu, yushi, and especially fei cui (in 1771). After that, the Yunnan official Wu Daxun wrote extensively on gems and other minerals based on his personal experiences during 1772–1782, referring inter alia to “Yunnan” (actually Burmese) jade ([Dian] yu [滇] 玉), baoshi 寶石, tourmaline (bixiasui 碧霞髓), fei cui stone ( fei cui shi 翡翠石), and cuisheng shi 催升石. This account is significant because it indicates that the previous emphasis on Burmese baoshi had now shifted to Burmese jade, which received enormous attention. Burmese jade now was divided into three categories and classes: yu, fei cui shi, and cui sheng shi. The first and the third, according to Wu Daxun, were of inferior quality and hence not worth much, while the green type of fei cui shi was worth as much as baoshi:

Regarding the quality of fei cui stone, the whiter the better; as for its cui 翠 [green], the deeper the better. There are two types of cui, qing 青 [darkish green] and lü 綠 [yellowish green], while the qing kind is even better, and its value equals to baoshi.31

This emphasis on the cui color is typical for Burmese jade. During the 1770s–1780s the value of fei cui soared, and the best fei cui could even compete with baoshi. Another decade or two witnessed fei cui’s overtaking China’s traditional type of jade (nephrite) in price. Moreover, Wu Daxun was the last person who employed the term cuisheng shi; after him, it completely disappeared. After two centuries in circulation—it had been coined in 1583—cuisheng shi was abandoned partially because the Yunnanese had a better term: fei cui, which was on the rise in China, both in popularity and quantity.

Indeed, during the second half of the eighteenth century, Burmese jade made a great leap forward in China, in two senses. First, the term fei cui crystallized. From its debut in 1719 up to 1799, the usage of the word fei cui became more widespread. It was mentioned in 1771, between 1772 and 1782 intermittently, and again with exactitude in 1777, 1779, 1780 (twice), 1796, and 1799, and then even more frequently in the nineteenth century. From this period on, though other names were still used for Burmese jade, fei cui became most popular, and has remained so to the modern times. Second, the volume of Burmese jade exported into China must have increased dramatically. The Tengyue Zhouzhi by Tu Shuliang reflects the situation by 1790. It first points out that because gems gathered in Tengyue, their collective street name was changed from Babao jie 八保街 to Baibao jie 百寶街 (meaning “street of 100 kinds of gems”). Then the account states,

Today the commodities purchased [from Burma] by merchants to Tengyue include, first, gems [zhubao] and, second, cotton. Gems [bao] come in their uncut form [pu 璞], while cotton is carried in bales. [These are] transported on mules and horses which crowd the roads. Currently at the provincial capital there are many jade-cutting shops [ jie yu fang 解玉坊], the noise of cutting goes on day and night. [The jade] is all from Tengyue, while the cotton bales travel to Guizhou.32

Apparently, zhubao and bao mainly refer to Burmese jade as the word pu is used exclusively for jade, while jade-cutting shops are clearly mentioned. It is notable that this source lists jade before cotton, demonstrating the crucial role of jade in the Qing-Burmese trade during this period.

Another source also demonstrates the large-scale jade trade between Burma and China. By the 1790s the price of fei cui had surpassed the age-old conventional type of jade from Xinjiang. In 1793, the famous scholar Ji Yun 紀昀 (1724–1805) wrote:

The value of things is dependent on the fashion of their time and [hence cannot be] fixed. [I] recall when I was young, ginseng, coral, and lapis lazuli were not expensive, [but] today [they are] increasingly so; turquoise and tourmaline were extremely expensive, [but] today [their prices are] increasingly reduced; fei cui jade [ fei cui yu 翡翠玉] of Yunnan at that time was not considered as jade . . . [but] at present it is seen as precious curio [baowan 寳玩], [and its] price far exceeds the genuine jade [zhenyu 真玉] [from Xinjiang]. . . . Prices of goods are so different in fifty to sixty years, let alone in several hundred years!33

Table 1 contains some post-1800 information in order to show the triumph of fei cui. Despite the records of baoshi, the term fei cui overwhelmingly dominates the picture. The 1887 edition of the gazetteer of Tengyue arranges all the gems under the rubric of yu, in a sharp contrast to Ni Tui’s 1719 arrangement, which includes all the gems under the baoshi category. This demonstrates that baoshi and fei cui had switched places, with the latter dominating, if not monopolizing the export trade. Statistics are lacking for the gem trade between China and Burma for the period prior to 1800, but large quantities of jade were exported to China during the nineteenth century and the early twentieth.34 Jade consumption in China in these two centuries had reached a new high.35 By contrast, there are no statistics on baoshi, which implies that, relative to fei cui, it was far less important.

Conclusion: The Gem Trade as a Chinese Business

The first written Chinese record of Burmese jade appeared around 1475, while the term fei cui referring to Burmese jade appeared in 1719. However, the appearance of the term fei cui is significant not only in itself, but also in that it registers a transition from an “age of baoshi” to an “age of jade” in the history of Sino-Burmese gem trade. Its emergence demonstrates that Chinese tastes in gemstones had shifted. Behind this shifting were deeper social and cultural forces at work.

Fei cui’s trajectory in China coincides with the trend of jade consumption in Qing China as described by Yang Boda. The first 115 years (1644–1759) comprised the first, or slow-growth, phase. This was a transitional period from the Ming to Qing, when style was still dominantly Ming and few jade works were made. The next fifty-two years (1760–1812) comprise the second phase, or the booming period, which witnessed the socioeconomic recovery of China. Many jade-cutting shops were opened, especially after the Qing started to control the sources of jade in Xinjiang, after the rebellions there were suppressed. Hence, in terms of raw jade supply, places of jade works, procedures of jade-cutting, the distribution of jade craftsmen, classifications of Qing jade, techniques of jade carving, as well as the size of jade works, this was a peak period in the history of jade in premodern China.36

In particular, the Qianlong emperor (r. 1736–1795) was an especially ardent jade lover and connoisseur, and his personal hobby became the most important driving force behind the “jade mania” in Qing China. One modern scholar states that Qinglong “shiyu chengpi 嗜玉成癖” meaning his being obsessed with or addicted to jade, and he composed 848 poems altogether on jade (though none on Burmese fei cui).37

China’s impact on Southeast Asian history is exemplified by the Sino-Burmese gem trade. One probably can say with justification that it was the Chinese who gave life and history to Burmese gem mining and exports, particularly jade. It started with the Mongol invasion of Burma in the thirteenth century, and the Mongols’ search for local gemstones. The Mongols taught the Han Chinese people to appreciate gemstones, including those from Burma, and the Chinese after the Mongols indeed followed that teaching. The huge demand in Ming times, especially from the mid-fifteenth century, created a fever for gemstones, particularly baoshi, across China and thus influenced Burmese history (the rise of the Shans in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries) in a significant way.

If Burmese baoshi benefited from a mix of Burmese, Indian, and European stimuli, then Burmese jade was a thoroughly Chinese business (hardly surprising, as the Chinese have been jade lovers since prehistoric times). Indeed, Burmese jade had nothing to do with Indians and Europeans. The Europeans had been fascinated by Burmese rubies since the fifteenth century and left with numerous accounts.38 But they did not mention jade and the jade mines in Upper Burma until the early nineteenth century, when unfamiliarity led them to call it “noble serpentine.”39 As late as the nineteenth century, one Chinese source commented that “[Burmese] green jade [cuiyu 翠玉] is only exported to China, whereas Westerners prize rubies.”40

This is true to this day, as the Chinese people within China and overseas continue to dominate the jade market. Important events and consumption waves in China have substantially influenced Burma’s gem business in the past, and do so still. For instance, for the wedding of the Qing emperor Tongzhi, in 1872, four lakhs (400,000) of rupees were expended at Guangzhou in buying Burmese jade, and “a great impulse was thereby given to the jade trade in Burma.” The total cost of Guangxu’s (Tongzhi’s successor) wedding, in 1889, was 5,500,000 liang of silver, with 80 percent on purchasing dowries, clothes, gold and silver vessels, pearls, fei cui, and so on.41 Chinese consumers since the Reform Era in the twentieth century, especially in recent decades, have been driving the mining of and trade in fei cui in northern Burma. Even now, the terminology and classification of fei cui follow the Chinese convention.42

Even the Burmese demand had little to do with the jade business by the eighteenth century and thereafter. The long title of the Burmese king throughout history—such as “Proprietor of all kinds of precious stones, of the mines of Rubies, Agate, Lasni, Sapphires, Opal; also the mines of Gold, Silver, Amber, Lead, Tin, Iron, and Petroleum . . .”—which in slightly various forms frequently appears in Burmese chronicles and other historical sources, never includes jade.43 It was not until the late eighteenth century that the Burmese king started to realize the value of jade and thus to regulate it.44 From around the 1820s the Burmese king added “jade” to the numerous possessions in his title ('Possessor/owner of mines of gold, silver, rubies, amber and noble serpentine [jade]'), and meanwhile also presented jade to the Chinese emperor and some European monarchs.45

The Chinese gave life and history to Burmese gems, particularly fei cui. Thus the history of Burmese jade well illustrates how China, in its desire for luxuries, has been a driving force behind the discovery and export of exotic goods from Southeast Asia, and by extension, this region’s economic growth and state formation.46

About the Author

Dr. Sun Laichen is a history professor specializing in early modern Southeast Asian history, associated with California State University, Fullerton (CSUF) and the University of Chicago Press, and is a published author and editor in his field. He has been cited in academic circles for his work on topics such as the Ming Dynasty's role in China's southern expansion.

Acknowledgements

I thank Michael Aung-Thwin, Sylvie Pasquet, Wu Yongping, Liu Zhen’ai, Liu Shiuh-feng, Wang Chunyun, Yamazaki Takeshi, and Koizumi Junko for help with sources, and Wen-Chin Chang and Eric Tagliacozzo for comments. Special thanks go to Victor Lieberman for his meticulous reading of the draft of this essay and for his extensive and constructive comments. The Visiting Fellowship from the Center for Southeast Asian Studies of Kyoto University in 2008 allowed me to complete this paper.

Editor's Note

This article was first published as:

-

Sun, L. (2011) From baoshi to feicui: Qing-Burmese gem trade, C. 1644–1800 In Chinese Circulations: Capital, Commodities, and Networks in Southeast Asia, Edited by Tagliacozzo, E. and Chang, W.-C., Duke University Press, pp. 203–221.

The original text has been edited slightly for style and also to align the nomenclature to the latest (2025) understanding.

[need Chinese text for all Chinese titles with English title translations; city of publication; publisher; total number of pages for books, page range for articles]

- In the West, the word "jade" is used as an umbrella term for two different ornamental rocks. Burmese fei cui is a rock composed of a mixture of three different pyroxene minerals, jadeite, omphacite and kosmochlor, while nephrite (Hetian yu; 和田玉) describes a rock made of the amphibole minerals, tremolite and actinolite. Previously the term "jadeite" was used for all pyroxene jades, but this has now been changed because one cannot use a mineral name to describe a rock. (S. Howard Hansford, 1948, p. 15). In addition, the hardness of jadeite is Mohs 7, while nephrite is 6–6.5. For convenience, I use the term jade for Burmese fei cui, except on several occasions. ↩︎

- Sun Laichen, “The Mongols and the Asian Gem Trade” (forthcoming). ↩︎

- For example, Xia Guangnan, Zhong Yin Mian dao jiaotong shi 中印緬道交通史 (Shanghai: Zhonghua shuju, 1948); Lan Yong, Nanfang sichou zhilu 南方絲綢之路 (Chongqing: Chongqing daxue chubanshe, 1992). ↩︎

- This is because jade had penetrated into and become entrenched in Chinese cultural life to such a degree that it became a separate category in Chinese gemological classification, and the juxtaposition of baoshi and yushi 玉石 (jade) in modern Chinese classification reflects this division. In the Western usage, however, “precious stones” include jade and fei cui as well. ↩︎

- Sun Laichen, “Shan Gems, Chinese Silver, and the Rise of Shan Principalities in Northern Burma, c. 1450–1527,” Southeast Asia in the Fifteenth Century: The Ming Factor, ed. Geoff Wade and Sun Laichen (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 2010), 169–96. ↩︎

- Xu Xiake, Xu Xiake youji jiaozhu 徐霞客遊記校注, annotated by Zhu Huirong (Kunming: Yunnan renmin chubanshe, 1999), 1020, 1106, 1113–34. ↩︎

- This is better known as jieyu sha 解玉沙 and other names in Chinese texts. See Zhang Hongzhao, Shi ya 石雅 (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1993), 132–34. ↩︎

- Ya(hu)qing and zumulü are derived from Arabic or Persian yaqut (meaning “ruby”) and zumurrud (literally means 'emerald,' a beryllium aluminum silicate, the most valuable of the beryl group; but in this context it should refer to a greenish gem), respectively. See Aḥmad ibn Yusuf Tifashi, Arab Roots of Gemology: Ahmad ibn Yusuf al Tifaschi’s Best Thoughts on the Best of Stones (Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press, 1998), 182, 192. Two late Ming sources—Gu Yingtai, Bowu yaolan 博物要覽 (Changsha: Shangwu yinshuguan, 1941), 6:44, and a poem included in Xuan Shitao, Yongchang fuzhi 永昌府志 ([S.1.: s. n.,] woodblock print, 1785), 25:33a—use yahu qing 鴉鶻青 and yaqing 鴉青, respectively, for Burmese rubies. ↩︎

- Liu Kun, Nanzhong zashuo 南中雜説 (Taibei: Yiwen yinshuguan, 1970), 18a–20b. ↩︎

- Song Yingxing, Tiangong kaiwu 天工開物 (Changsha: Yuelu shushe, 2004), 394–95; Gu Yingtai, Bowu yaolan, vol. 6. ↩︎

- Richard W. Hughes, Ruby & Sapphire (Colorado: RWH Publishing, 1997), 329. ↩︎

- Xu Jiong, Shi Dian zaji 使滇雜記 (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1983), 14a; Shitongkui 釋同揆, Erhai congtan 洱海叢談, in Fang Guoyu, Yunnan shiliao congkan 雲南史料叢刊 (Kunming: Yunnan daxue chubanshe, 2001) (henceforth YSC), 11:371; Chen Ding, Dian youji 滇遊記, in YSC, 11:380–81. Chen Ding also mentions biyu, but it is a verbatim copy from Shitongkui, and thus does not count. ↩︎

- E.C.S. George, Ruby Mine District A (Rangoon: Superintendent, Government Printing and Stationery, 1961), 30–31;

Than Tun, The Royal Orders of Burma, A.D. 1598–1885 (Kyoto: Center for Southeast Asian Studies, 1983), 1:9, 165. ↩︎ - Xu Jiong, Shi Dian zaji, 14a; Ni Tui, Dian xiao ji 滇小記, in YSC, 11:127; Wu Daxun, Diannan wenjian lu 滇南聞見錄, in YSC, 12:28; Zhao Yi, Yanpu zaji 簷曝雜記 (1810; repr., Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1997), 57–58; Tan Cui 檀萃, Dianhai yuheng zhi 滇海虞衡志 (Taibei: Yiwen yinshuguan, 1967), 2:5a–7a. ↩︎

- Liu Wenzheng, Dian zhi 滇志 (Kunming: Yunnan jiaoyu chubanshe, 1991), 212. ↩︎

- Xu Jiong, Shi Dian zaji, 14a. [need Chinese text for titles and English translations] ↩︎

- According to one Chinese treatise on jade—Chen Xing’s Yu ji 玉記 (prefaced in 1864; repr., Mantuoluo Huage congshu 曼陀羅華阁叢書, 1902),” “Yuse 玉色,” 2a—“those that are as green (lü 綠) as cui feather (cuiyu 翠羽) are called lu 瓐 (綠如翠羽曰瓐).” “Jin’gang” should be jin’gangzuan 金剛鑽 (see table 1 in this essay). ↩︎

- YSC, 11:127. ↩︎

- Tifashi, Arab Roots of Gemology, 204; Song Xian, “‘Huihui shitou’ he Alabo baoshixue de dongchuan 回回石頭和阿拉伯寳石學的東傳,” Huizu yanjiu 回族研究 3 (1998): 59; Fuge, Tingyu congtan 聼雨叢談 (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1997), 143. Zhang Shizhao in the Shi ya (77–79, 83, 108) discusses this term and its variations, but says nothing about its etymology. In modern usage it has been called bixi 碧璽. For other transliterations of this term, see table 1 in this essay. ↩︎

- Tao Zongyi 陶宗儀, Nancun cuogeng lu 南村輟耕錄 (1366; repr., Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1980), 84. ↩︎

- Tu Shulian, Tengyue zhouzhi 騰越州志 (Taibei: Chengwen chubanshe, 1967), 3:33. ↩︎

- Sources for table 1 include Chen Wen, Jingtai Yunnan tujing zhishu 景泰雲南图經志書 (prefaced in 1455; repr., Kunming: Yunnan minzu chubanshe, 2002), 346; Ming Xianzong shilu 明憲宗實錄 (Taibei: Zhongyang yanjiuyuan yuyan lishi yanjiusuo, 1967), 168:4b, 174:8a; Zhang Zhicun, Nanyuan manlu 南園漫錄 (prefaced in 1515; repr., Beijing: Shumu wenxian chubanshe, 1988), 7:1; Tian Rucheng, Xingbian jiwen 行邊記聞 (prefaced in 1560), in YSC, 4:605; Chen Zilong et al., Ming jingshi wenbian 明經世文編 (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1962), 1:665; Zhou Jifeng 周季鳳, Zhengde Yunnan zhi 正德雲南志 (Shanghai: Shanghai shudian, 1990), 14:4a (vol. 2 also mentions that bitianzi 碧瑱子 was produced in Anning 安宁 nearby Kunming, Yunnan, but this is no doubt not fei cui, but rather a kind of green stone [2:9b]); Xinanyi fengtu ji 西南夷風土記, in YSC, 5:493; Shen Defu, Wanli yehuo bian 萬曆野獲編 (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1997), 907; Xie Zhaozhe, Dian lue 滇略, in YSC, 6:690; Liu Wenzheng, Dian zhi, 115, 212, 748 (115, records that it was made into cups to cure dystocia); Xu Xiake youji jiaozhu 徐霞客遊記校注 (Kunming: Yunnan renmin chubanshe, 1999), 1020, 1106, 1113–14; Fang Yizhi, Wuli xiaoshi 物理小識, Xu baizi quanshu 續百子全書 (Beijing: Beijing tushuguan chubanshe, 1998), 14a; Liu Kun, Nanzhong zashuo, 18a–20b; Xu Jiong, Shi Dian zaji, 14a; Shitongkui, Erhai congtan, in YSC, 11:371; Fan Chengxun and Wu Zisu, Yunnan tongzhi (prefaced in 1691; repr., Beijing: Shumu wenxian chubanshe, 1988), 12:8; Chen Ding, Dian youji, in YSC, 11:380–81; Luo Lun and Li Wenyuan, Yongchang fuzhi 永昌府志 (Beijing: Shumu wenxian chubanshe, 1987), 10:7–8; Ni Tui, Dian xiao ji, 126–27; Qing dang 清檔, Gong dang 貢檔, and Zalu dang 雜録檔, cited in Yang Boda 楊伯達, “Cong wenxian jizai kao fei cui zai Zhongguo de liuchuan” 從文獻記載考翡翠在中國的流傳, Gugong Bowuyuan yuankan 故宮博物院院刊 2 (2002): 14–15; Ertai and Jin Daomo, Yunnan tongzhi 雲南通志 (prefaced in 1736; repr., Taibei: Taiwan shangwu yinsshuguan, [1983]), 27:13; Zhang Hong, Diannan Xinyu 滇南新語 (Taibei: Yiwen yinshuguan, 1968), 12a–13b; Zhang Yong, Yunnan fengtu ji 雲南風土記, in YSC, 12:50; Fu Xian, Miandian suoji 緬甸瑣記, in Yu Dingbang 余定邦 and Huang Zhongyan, Zhongguo guji zhong youguan Miandian ziliao huibian 中国古籍中有关缅甸资料汇 (henceforth huibian) (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 2002), 1161; Wang Chang, Zhen Mian jilue 征緬紀略, in huibian, 1103; Zhou Yu, Congzheng Miandian riji 從征緬甸日記 (Taibei: Yishi chubanshe, 1968), 4b; Qing shilu 清實錄, vol. 899, Qianlong 36/12, 1125b; Qing shilu, vol. 1031, Qianlong 42/4, 819b; Qing shilu, vol. 1484, Qianlong 60/8, 840; Qing shilu, vol. 134, Jiaqing 9/9, 822b; Qing shilu, vol. 320, Jiaqing 21/7, 240b; Qing shilu, vol. 328, Daoguang 19/11, 1160a; Qing shilu, vol. 22, Tongzhi 1/3, 596a (for the Qing shilu references, see the Academia Sinica website, http://www.sinica.edu.tw/); Wu Daxun, Diannan wenjian lu, 18, 27–29; Xie Qinggao, Hai lu 海録, in huibian, 1081; Tu Shulian, Tengyue zhouzhi, 3:26–29, 33; Zhao Yi, Yanpu zaji, 57–58; Ji Yun, Yuewei caotang biji 閱微草堂筆記 (Beijing: Zhonghua gongshang lianhe chubanshe, 2001), 1:427; Tan Cui, Dianhai yuheng zhi, 2:5a–7a; Guifu, Dianyou xubi 滇游續筆, in YSC, 12:82; Xu Zhongyuan, Sanyi bitan 三異筆談 (Shanghai: Jinbu shuju, 1920), 2:14b; Peng Songyu, Mian shu 緬述, in huibian, 1193; Gong Chai, Miandian kaolue 緬甸考略, in huibian, 1184; Yu Yue, Chaxiangshi congchao 茶香室叢鈔 and Jiang Chabo, Nanru kuyu 南溽楛語, both cited in Deng Shupin, “fei cui xutan” 翡翠續談, Gugong wenwu yuekan 故宮文物月刊 2.5 (1984): 41; Xie Kun, Jinyu suosui 金玉瑣碎, cited in Deng Shupin, “Tan fei cui” 談翡翠, Gugong wenwu yuekan 2.3 (1984): 4; Chen Xing, Yu ji, “chuchan” 出産, 1b; Wang Zhi 王芝, Haihe riban 海客日譚, in huibian, 1215, 1223, 1234, 1237; Cen Yuying, Cen Xiangqinyingong zaogao 岑襄勤公奏稿, in huibian, 416; Huang Maocai, Xiyou riji 西輶日記, in huibian, 1201; Wu Qizhen, Miandian tushuo 緬甸圖説, in huibian, 1171, 1177, 1181; Chen Zonghai and Zhao Ruili, Tengyue tingzhi 騰越廳志 (prefaced in 1887; repr., Taibei: Chengwen chubanshe, 1967), 3:3–4; Tang Rongzuo, Yu shuo 玉説, cited in Yang Boda, “Cong wenxian jizai,” 20–22; Xue Fucheng, Chushi Ying Fa Yi Bi siguo riji 出使英法意比四囯日記, in huibian, 1307,1310, 1312, 1326; Yao Wendong, Jisi guangyi bian 集思廣益編, in huibian, 1401, 1403–4, 1409. ↩︎

- Xinanyi fengtu ji, 493. ↩︎

- Xie Zhaozhe, Dian lue, 700. ↩︎

- A Burmese jade bracelet was found in a tomb in Tengchong whose owner lived from 1586 to 1646. Yang Boda, “fei cui chuanbo de wenhua beijing jiqi shehui yiyi” 翡翠傳播的文化背景及其社會意義, Gugong xuekan 故宮學刊 1 (2004): 131–32. ↩︎

- The term cuisheng shi 催生石 is also used in other Chinese texts and contexts such as India and Tibet (Zhang Hongzhao, Shi ya, 82–83, 111, 180–81). However, it seems to be that the 1583 instance in the Upper Burma context is the earliest record. ↩︎

- J.S. Furnivall and U Pe Maung Tin, eds., Cambu’ di pa u” chon’ ” kyam’ ” (Yangon: Mran’ ma nuin’’ nam su te sa na ‘a san,’” 1960), 48; Than Tun, English translation of the Cambu’ di pa u” chon’ ” kyam’ ” (manuscript), 58; Khin Maung Nyunt, “History of Myanmar Jade Trade till 1938,” Traditions in Current Perspective: Proceedings of the Conference on Myanmar and Southeast Asian Studies, 15–17 November 1995, Yangon (Yangon: Universities Historical Research Centre, 1996), 283–85. ↩︎

- Mhan’ nan’ ” maha rajavan’ to’ kri” (Yangon: Sa Tan’” nhan’ Ca Nay’ Jan’” Lup’ Nan,’” Pran’ Kra” Re” Van’ Kri” Thana, 1992–1993), vol. 1, 204, passim. ↩︎

- Nishida Tatsuo 西田龍雄, Mentenkan yakugo no kenkyu: Biruma gengogaku Josetsu 緬甸館譯語の研究: ビルマ言語學序説 [A study of the Burmese-Chinese vocabulary Miandianguan yiyu: An introduction to Burmese linguistics] (Kyoto: Shokado, 1972), 135, 140–41 (the term fei cui appears on p. 102 but refers to kingfisher); Miandian fanshu 緬甸番書 (unpublished manuscript at Fu Sinian Library, Academia Sinica, Taibei, A437.774.v.1). ↩︎

- In YSC, 12:50. ↩︎

- In YSC, 12:27–29. ↩︎

- Tu Shulian, Tengyue zhouzhi, 3:26, 28. ↩︎

- Ji Yun, Yuewei caotang biji, 1:427. ↩︎

- W.A. Hertz, Myitkyina District (repr., Rangoon: Superintendent, Government Printing and Stationery, 1960), 121–23; Khin Maung Nyunt, “History of Myanmar Jade Trade till 1938,” 277. ↩︎

- Wang Chunyun, “Guangzhou Yuqixu he fei cui wenhua lishi chutan” 广州玉器墟和翡翠文化历史源流初探 (available at Guoying Keji Wangzhan 国英科技网站 http://www.guoying.com.cn/); Qiu Zhili 丘志力 et al., “Qingdai fei cuiyu wenhua xingcheng chutan” 清代翡翠玉文化形成探释, Zhongshan Daxue Xuebao 中山大学学报 47.1 (2007): 46–50. ↩︎

- “Qingdai gongting yuqi 清代宫廷玉器,” Gugong Bowuyuan yuankan 1 (1982): 49–52. ↩︎

- Yin Zhiqiang, Guyu zhimei 古玉至美 (Taibei: Yishu tushu gongsi, 1993), 30; Deng Shupin, “Tan fei cui” 談翡翠, Gugong wenwu yuekan 故宮文物月刊 2.3 (1984): 10. ↩︎

- Hughes, Ruby & Sapphire, chap. 12; Khin Maung Nyunt, “History of Myanmar Jade Trade till 1938,” 255–56. ↩︎

- John Crawfurd, Journal of an Embassy from the Governor General of India to the Court of Ava (London: R. Bentley, 1834), 2:194; Henry Yule, A Narrative of the Mission to the Court of Ava in 1855 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1968), 146, 265; Khin Maung Nyunt, “History of Myanmar Jade Trade till 1938,” 261–63. ↩︎

- Yao Wendong, Jisi guangyi bian, in huibian, 1404. ↩︎

- Hertz, Myitkyina District, 130; Li Pengnian, “Guangxu di dahun beiban haoyong gaishu” 光緒帝大婚備辦耗用概述, Gugong bowuyuan yuankan 2 (1983): 80–86, 79. ↩︎

- Khin Maung Nyunt, “History of Myanmar Jade Trade till 1938,” 270–21; Kyi” sai Ññvan’’ Nuin’, Kyok’ myak’ ratana abhidhan’ (Yangon: A mran’ sac’, 1989), 64, 85–89; U” Ñan’ San,’” Mran’ ma’ kyok’ cim’ ” ([Yangon]: Pan’su Bhumibeda Lup’ nan’” mya” Chon’ rvak’ mhu Samavayama A san,’” 1993), 195, 197. ↩︎

- Mhan’ nan’ ” maha rajavan’ to’ kri”; U” Mon’ Mon’ Tan’, Kun’ ” bhon’ chak’ maha rajavan’ to’ kri” (Yangon: Lay’ ti Manduin’ Pum nhip’ tuik’, 1967–1968) (hereafter as Kun’ ” bhon’ chak’), 3 vols. The quote is from Michael Symes, An Account of an Embassy to the Kingdom of Ava, Sent by the Governor-General of India, in the Year 1795 (Westmead, Hants., England: Gregg International, 1969), 487. ↩︎

- Khin Maung Nyunt, “History of Myanmar Jade Trade till 1938,” 260–66, 283–85. ↩︎

- Kun’ ” bhon’ chak’, 2:361, 3:30, 3:34; Henry Burney, “Some Accounts of the Wars between Burma and China, together with the Journals and Routes of Three Different Embassies Sent to Pekin by the King of Ava; Taken from Burmese Documents,” Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal 6.2 (June–July 1837): 437, 542; Henry Burney, “Embassies between the Court of Ava and Peking: Translated from Burmese Chronicles,” Chinese Repository 9.4 (November 1840): 469. With regard to the Burmese king offering jade to the Chinese emperor and certain European monarchs, see Kun’ ” bhon’ chak’, 2:362, 3:35; Burney, “Some Accounts of the Wars between Burma and China,” 438, 543; Burney, “Embassies between the Court of Ava and Peking,” 470; Cen Yuying, Cen Xiangqingong, in YSC, 9:416; U” Ñan’ San,’” Mran’ ma’ kyok’ cim,’ ” 127–28; Khin Maung Nyunt, “History of Myanmar Jade Trade till 1938,” 254. ↩︎

- For the Chinese search for fei cui in modern times, see Wen-Chin Chang’s piece herein; for the impact of Chinese demand for forest produces on Borneo’s ecology, see Eric Tagliacozzo’s piece, also in this volume. ↩︎

References

-

al-Tīfāshī, A.i.Y. and Huda, S.N.A. (1998) Arab Roots of Gemology: Ahmad ibn Yusef Al Tifaschi’s Best Thoughts on the Best of Stones. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 272 pp.

-

Chang, W.-C. (2011) From a Shiji episode to the forbidden jade trade during the socialist regime in Burma In Chinese Circulations: Capital, Commodities, and Networks in Southeast Asia, Edited by Chang, W.-C., Durham & London: Duke University Press, pp. 454–479.

-

Crawfurd, J. (1829) Journal of an Embassy From the Governor-General of India to the Court of Ava, in the Year 1827. London: Henry Colburn, 2nd ed. 1834, 2 Vols., 605 pp.

-

Hansford, S.H. (1948) Jade and the kingfisher. Oriental Art, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 11–17.

-

Hertz, W.A. (1912) Burma Gazetteer: Myitkyina District. Rangoon: Superintendent, Govt. Printing and Staty., Volume A, reprinted 1960, 193 pp., map.

-

Hughes, R.W. (1997) Ruby & Sapphire. Boulder, CO: RWH Publishing, 512 pp.

-

Khin Maung Nyunt (1995) History of Myanmar jade trade till 1938. Universities Historical Research Centre, Traditions in Current Perspective: Proceedings of the Conference on Myanmar and Southeast Asian Studies, Yangon, 15–17 November, pp. 247–290.

-

Khin Maung Nyunt (2004) History of Myanmar’s jade trade till 1938 In Selected Writings of Dr. Khin Maung Nyunt, Yangon: Myanmar Historical Commission, pp. 11–51.

-

Sun, L. (2010) Shan gems, Chinese silver, and the rise of Shan principalities in northern Burma, c. 1450–1527 In Southeast Asia in the Fifteenth Century: The China Factor, Edited by Wade, G. and Sun, L., Singapore: National University of Singapore Press, pp. 169–196.

-

Symes, M. (1800) Account of an Embassy to the Kingdom of Ava. London: J. Debrett, 2 Vols., Vol. 2, see pp. 375–381.

-

Tagliacozzo, E. (2011) A Sino-Southeast Asian circuit: Ethnohistories of the marine goods trade In Chinese Circulations: Capital, Commodities, and Networks in Southeast Asia, Edited by Tagliacozzo, E. and Chang, W.-C., Duke University Press, pp. 432–454.

-

Than Tun (1989) The Royal Orders of Burma, A.D. 1598–1885. Kyoto: Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University, 10 Vols., Vol. 9, 319 pp. (see Vol. 9, p. 165).

-

Wade, G. and Sun, L., editor (2010) Southeast Asia in the Fifteenth Century: The China Factor. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 508 pp.

-

Xu, H. (1985) Annotated Travels of Xu Xiake [徐霞客游记校注]. [in Chinese], Kunming: Yunnan People’s Publishing House, 2 Vols., 1382 pp.

-

Yule, H. (1858) A Narrative of the Mission to the Court of Ava in 1855. London: Smith, Elder and Co., Reprinted by Oxford University Press, 1968, 391 pp.