This article discusses the factors that influence quality and what to look for when buying both fei cui and nephrite. A list of jade auction records is also included.

|

Fei Cui vs. Jadeite Since 1863, gemologists have referred to jades composed of clinopyroxenes as "jadeite." However analyses over the past few decades have shown that what we call jadeite is actually a rock composed of varying amounts of jadeite, omphacite and kosmochlor. Since it is impossible without destructive testing to determine the percentages of each mineral species in an entire sample, the Chinese gem trade has adopted the traditional term "fei cui" (翡翠 = 'kingfisher') as an umbrella moniker to describe this rock. As of July 2023, Lotus Gemology has done the same on our reports and in our writings. For more on this topic, see From Fei Cui to Jadeite and Back. |

A tale of two stones

For some ten thousand years, jade (Chinese: yù; 玉) has been treasured by the Chinese. One of the earliest domestic sources of the stone was the White Jade (Yurungkash) and Black Jade (Karakash) Rivers near the town of town of Hetian (和田; a.k.a. Hotan, Khotan) in western China's Xinjiang Province (Chinese Turkestan) (Laufer, 1912). From these deposits comes a creamy white to greenish stone, with the most valuable being pure white. Sitting astride the old Silk Road, it first entered China proper by traders from Central Asia.

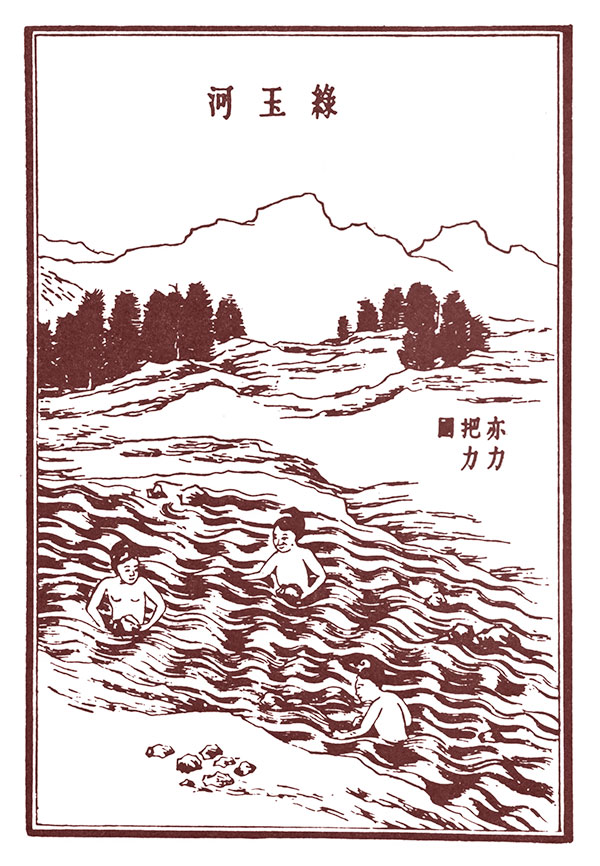

Figure 1. Jade pickers in the Karakash river near Hetian (a.k.a. Khotan) in western China's Xinjiang Province. Jade is said to be masculine and thus would be attracted to females. Autumn moonlit nights were thought to be the best time to find jade, as it was believed that the jade would reflect the moonlight. From the T'ien Kung K'ai Wu by Sung Ying-hsing, a 1637 AD Chinese encyclopedia.

Figure 1. Jade pickers in the Karakash river near Hetian (a.k.a. Khotan) in western China's Xinjiang Province. Jade is said to be masculine and thus would be attracted to females. Autumn moonlit nights were thought to be the best time to find jade, as it was believed that the jade would reflect the moonlight. From the T'ien Kung K'ai Wu by Sung Ying-hsing, a 1637 AD Chinese encyclopedia.

While the discovery of fei cui in Myanmar dates back to the 6th Century AD or earlier, and its first entry into China was dated by British Sinologist William Warry in the 13th Century (Hertz, 1912), it did not come into prominance until the Qing Dynasty (1644–1914). When Emperor Qianlong saw a piece of this white-to-bright green jade, he was immediatlely besotted. Learning it came from a wild country south of Yunnan, he sent columns of troops down to secure a supply. But even the crack Chinese armies were no match for the difficult terrain and fierce Kachin hill people. They returned empty handed, beaten back by malaria, mud and tribespeople who toyed with the outsiders from the north. Thereafter, Chinese traders generally never attempted to venture into the hills to the mines, content to deal with the Kachin on the comparatively tranquil plains at Mogaung.

A full summary of the Burmese deposits is contained in Hughes et al. (1996–97), Hughes (1999) and Hughes et al. (2000). The Chinese understood this material was different from the Hetian jade, and named the vivid green variety feicui (翡翠) or kingfisher jade, due to its resemblance to the color of the feathers of the kingfisher bird.

By the mid-16th century, the Spanish had spread across much of the New World. In the process they discovered a stone treasured throughout Mesoamerica. Mistakenly believing it was used for pains of the side and lower back, they named it piedra de ijade (stone of the flank of the lower back) (Monardes, 1569). In French this became éjade and then jade, in Italian giade and jade in English. In Dog Latin it was lapis nephriticus (stone good for the kidneys). Mesoamerican jade was the mineral now called fei cui (Hacking, 2007). Hacking continues:

Sweden 1758: Nephrite. Axel von Cronstedt (the geologist who named nickel) renamed lapis nephriticus ‘Nephrit’ in Swedish. That became the German scientific name when he was translated, 1780. It entered A.G. Werner’s classic system (1791). The mineralogists probably, but not certainly, had nephrite samples before them. ‘Nierenstein’ was used in German much earlier, meaning stone good for the kidneys, along- side its other meaning, kidney stone (calculus). In English ‘nephritic stone’ was common.

– Ian Hacking, 2007, "The contingencies of ambiguity"

In 1846, French chemist Alexis Damour did the first chemical analysis of nephrite, finding it to be an amphibole (Damour, 1846). Later, following the British and French armies' 1860 sacking of Beijing's Summer Palace, where many Chinese jade objects were stolen and then made their way to Europe, Damour again analyzed jade. He found the intense green stones to be chemically different from the white-to-pale green nephrite jade, and named the new stone "jadeite" (Damour, 1863; Hacking, 2007).

Figure 2. Map of China showing the location of major jade mines, markets, and carving centers. The major source of Chinese nephrite is Hotan (a.k.a. Khotan) in western China's Xinjiang Province, while fei cui comes from the Hpakan region of Upper Myanmar (Burma). Map: Richard W. Hughes. Click on the map for a larger image.

Figure 2. Map of China showing the location of major jade mines, markets, and carving centers. The major source of Chinese nephrite is Hotan (a.k.a. Khotan) in western China's Xinjiang Province, while fei cui comes from the Hpakan region of Upper Myanmar (Burma). Map: Richard W. Hughes. Click on the map for a larger image.

Jade Today

The term jade today is used for two different rocks, fei cui and nephrite. While each of these jade cousins shares certain characteristics, in other ways they could not be more different. Yin/Yang. These are two different bridges to heaven.

Although I have been involved with jade since 1977, it was only when I visited China's famous Guangzhou jade market in 2009 that I was exposed to Chinese nephrite. It was love at first sight; suddenly I understood the deeper attraction of "jade." While the author once wrote that only fei cui had value as a gem material, this opinion was born of ignorance. The white Chinese nephrite is a lovely gem material possessing a sublime beauty all its own and today fetches prices that compete with the finest imperial fei cui. To date, the best source of this white "mutton fat" nephrite is near Hetian in western China's Xinjiang province.

Whereas fei cui is lipsticked gloss and neon-lit high-heels, the beauty of Chinese nephrite involves a far different experience, where depth and feeling rule. Having now experienced both worlds, I must say that, as I grow older, I tend to be drawn more and more to the world of nephrite. In summarizing the difference between the two materials, I'd say that fei cui is miniskirted eyes-wide-open candy. In contrast, nephrite involves encountering your lover in a dark room, where beauty is hidden by blindfold, and thus discovered via sweet caress and touch. Even the manner in which the gems are displayed is radically different. Fei cui struts her stuff under gaudy lights surrounded by the sparkle of diamonds; in contrast, nephrite is placed in front of the public like fine art, with dark backgrounds and generous space, befitting a stone that the Chinese consider to be more valuable than either silver or gold—the most precious substance on earth—literally the bridge to heaven.

Judging Quality

While a number of fanciful terms have been used to describe fei cui, its evaluation is similar to that of other gemstones in that it is based primarily on the "Three Cs" – color, clarity, and cut (fashioning). Unlike most colored stones, the fourth "C" – carat weight – is less important than the dimensions of the fashioned piece. However, two additional factors are also considered – the "Two Ts" – translucency (diaphaneity) and texture. In the following discussion, Chinese terms for some of the key factors are given in parentheses, with a complete list of Chinese terms for various aspects of jade given in Table 1.

Base material

One of the key concepts in understanding fei cui jade quality is that of the base material (in Thai this is termed nua – the 'meat'). This term describes the quality of the material itself, completely separate from color.

Translucency

The best fei cui is semi-transparent; opaque fei cui or material with granular cloudy patches typically has the least value. It is interesting to note that even if the overall color is uneven or low in saturation, fei cui can still be quite valuable if it has good transparency.

Texture

In jade, texture is intimately related to transparency. Typically, the finer the texture, the higher the transparency. Further, the evenness of the transparency depends on the consistency of the grain size. Top fei cui has an extremely fine grained texture. This allows it to take a glassy polish with no undercutting or dimpling.

.jpg) Figure 3. fei cui Colors

Figure 3. fei cui Colors

The three basic elements of any color are hue position (top), saturation and tone (bottom). Note that saturation and tone are interrelated. As saturation increases, so does tone (lower left). However, there reaches a point where increasing absorption of light (increasing tone) results in a decrease in saturation (lower right). Illustration © Richard W. Hughes

Color (se)

This is the most important factor in the quality of fashioned fei cui. As per standard color nomenclature, fei cui's colors are best described by breaking them down into the three color components: hue (position on the color wheel), saturation (intensity), and tone (lightness or darkness). The Doubly Fortunate necklace shown below is an excellent example of top-quality hue, saturation, tone, and color distribution.

Figure 4. Doubly Fortunate

Figure 4. Doubly Fortunate

In 1997, this necklace of 27 perfectly matched beads cut from the famous "Doubly Fortunate" fei cui boulder set a new record for jade, selling for an amazing US$9,390,922. Image © Christie's

For fei cui, the intensity of the green color, combined with a high degree of translucency are the key factors in judging value. Stones which are too dark in color or not so translucent are less highly valued. Color distribution must also be taken into account.

Note that top color in fei cui jade is only realized when the base material (meat) is of fine quality.

Hue (zheng): Top-quality fei cui is pure green. While its hue position is usually slightly more yellow than that of fine emerald and it never quite reaches the same saturation of color, the ideal for fei cui is a fine "emerald" green. No brown or gray modifiers should be present in the finished piece.

Saturation (nong): This is by far the most important element of green and lavender fei cui color. The finest colors appear intense from a distance (sometimes described as 'penetrating'). Side-by-side comparisons are essential to judge saturation accurately. Generally, the more saturated the hue is, the more valuable the stone will be. A related factor is referred to as cui by the Chinese. Colors with fine cui are variously described as brilliant, sharp, bright, or hot. This is the quality that makes "shocking" pink shocking and "electric" blue electric.

Tone (xian): The ideal tone is medium – not too light or too dark.

Distribution (jun): Ideally, color should be completely even to the unaided eye, without spotting or veins. In lower qualities, fine root- or vein-like structures that contrast with the body color of the stone may be considered attractive. However, dull veins or roots are less desirable. Any form of mottling, dark irregular specks, or blotches that detract from the overall appearance of the stone will reduce the value.

| Chinese Name | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Yu | Broad Chinese word for any mineral aggregate (rock) that is attractive, tough and durable enough to be carved. This word has no equivalent in English. It includes many types of rock such as nephrite, Dushan jade, lapis lazuli, turquoise, jasper, agate and more. Fei cui is a special type of yu that is in a class by itself. |

| Hetian yu | Nephrite from China. While this originally designated nephrite from Hetian (Khotan), Xinjiang, China, it is now used for all Chinese nephrite. |

| Ruan yu | Improper term that means 'soft jade'; it is used in place of nephrite, but the hardness differences between nephrite and fei cui are so slight as to be inconsequential; therefore this term should not be used. |

| Ying yu | Improper term that means 'hard jade'; it is used in place of fei cui, but the hardness differences between nephrite and fei cui are so slight as to be inconsequential; therefore this term should not be used. |

| Fei-ts'ui (feicui) | "Kingfisher" jade (pyroxene jade). |

| Lao keng | "Old mine" fei cui – fine texture. |

| Jiu keng | "Relatively old mine" fei cui – medium texture. |

| Xin keng | "New mine" fei cui – coarse texture. |

| Ying | Jadeite type with the highest luster and transparency. |

| Guan yin zhong | Semi-translucent, even, pale green fei cui. |

| Hong wu dong | Lesser quality than guan yin zhong, with a pale red mixed with the green. |

| Jin si zhong | "Golden thread" fei cui: vivid green evenly distributed; quite valuable. |

| Zi er cui | High-grade fei cui mined from rivers; also called bing zhong (“ice”) for high translucency. |

| Lao keng bo li zhong | Old-mine “glassy” fei cui (finer texture, more translucent). In Imperial green, the most valuable fei cui. |

| Fei yu | Red fei cui, named after a red-feathered bird. |

| Hong pi | "Red skin" fei cui cut from the red rind of a boulder. |

| Jin fei cui | Golden or yellow fei cui. |

| Shuangxi | Jadeite with both red and green. |

| Fu lu shou | Jadeite with red, green, and lavender. |

| Da si xi | Highly translucent fei cui with red, green, lavender, and yellow. |

| Wufu linmen | Jadeite with red, green, lavender, and yellow, plus white as the bottom layer. |

In contrast to fei cui, it is the absence of color that is a key factor in determining the value of the nephrite from western China, with "snow white" stones fetching huge prices today.

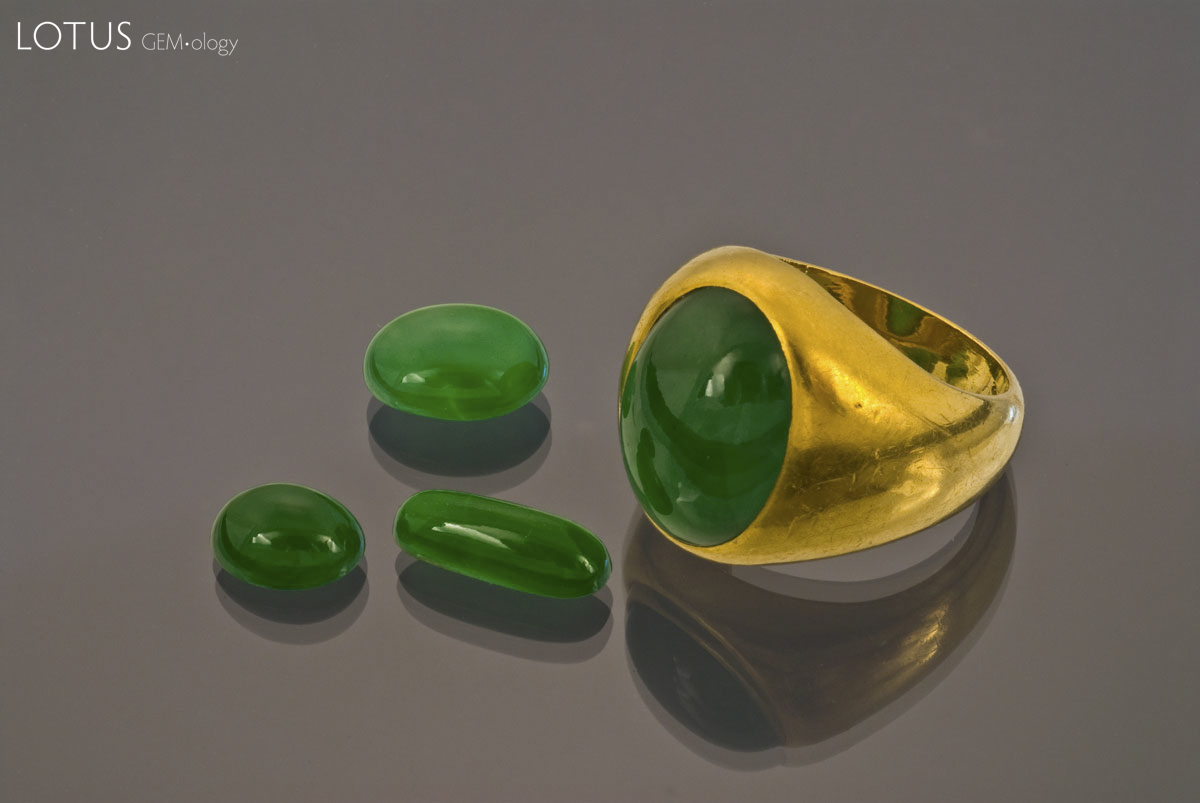

Figure 5. Fei-ts'ui Imperial fei cui ring and cabochons. Courtesy Pala International; photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Figure 5. Fei-ts'ui Imperial fei cui ring and cabochons. Courtesy Pala International; photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Clarity

In terms of clarity, fine fei cui should be free from noticeable or distracting inclusion defects. This refers to imperfections that impair the passage of light. The finest fei cui has no inclusions or other clarity defects that are visible to the naked eye. Typical imperfections are mineral inclusions, which usually are black, dark green, or brown, but may be other colors. Black spots easily visible to the eye are a particular problem because the Chinese associate them with bad luck. White spots (pollen) also are common, as are other intergrown minerals. The most severe clarity defects in fei cui are unhealed fractures, which can have an enormous impact on value because fei cui symbolizes durability and perfection. That said, virtually all fei cui has feathers that are visible under magnification.

Fashioning

More so than for most gem materials, fashioning plays a critical role in fei cui beauty and value. Typically, the finest qualities are cut for use in jewelry – as cabochons, bracelets, or beads. Cutters often specialize: one may do rings, another carvings, and so on.

Polish is particularly important with fei cui. Fine polish results in fine luster, so that light can pass cleanly in and out of a translucent or semi-transparent piece. One method of judging the quality of polish is to examine the reflection of a beam of light on the surface of a piece of fei cui. A stone with fine polish will produce a sharp, undistorted reflection, with no "orange-peel" or dimpling visible.

Following are a few of the more popular cutting styles of fei cui.

Cabochons

The finer qualities are usually cut as cabochons. One of the premium sizes – the standard used by many dealers' price guides – is 14 x 10 mm (Samuel Kung, pers. comm., 1997). Material used for cabochons is generally of higher quality than that used for carvings (Ou Yang, 1999), although there are exceptions.

With cabochons, the key factors in evaluating cut are the contour of the dome, the symmetry and proportions of the cabochon, and its thickness. Cabochon domes should be smoothly curved, not too high or too flat, and should have no irregular flat spots. Proportions should be well balanced, not too narrow or wide, with a pleasing length-to-width ratio (Ng and Root, 1984). The best-cut cabochons have no flaws or unevenness of color that is visible to the unaided eye.

Since the 1930s, double cabochons, shaped like the Chinese ginko nut, have been considered the ideal for top-grade fei cui, since the convex bottom is said to increase light return to the eye, thus intensifying color (Christie's, 1996). Stones with poor transparency, however, are best cut with flat bases, since any material below the girdle just adds to the bulk without increasing beauty. Hollow cabochons are considered least valuable (Ou Yang, 1999).

Traditionally, when fine fei cui cabochons are mounted in jewelry, they are backed by metal with a small hole in the center. The metal acts as a foilback of sorts, increasing light return from the stone. Also, with the hole one can shine a penlight through the stone to examine the interior, or probe the back with a toothpick to determine the contours of the cabochon base (Ng and Root, 1984). When this hole is not present, one needs to take extra care, as the metal may be hiding some defect or deception.

Beads

Strands of uniform fei cui beads are in greater demand than those with graduated beads. The precision with which the beads are matched for color and texture is particularly important, with greater uniformity resulting in greater value. Other factors include the roundness of the beads and the symmetry of the drill holes. Because of the difficulties involved in matching color, longer strands and larger beads will carry significantly higher values. Beads should be closely examined for cracks. Those cracked beads of 15 mm diameter or greater may be recut into cabochons, which usually carry a higher value than a flawed bead (Ng and Root, 1984).

Bangle Bracelets

Bangles are one of the most popular forms of fei cui jewelry, symbolizing unity and eternity. Even today, it is widely believed in the Orient that a bangle will protect its wearer from disaster by absorbing negative influences. For example, if the wearer is caught in an accident, the bangle will break so that its owner will remain unharmed. Another common belief is that a spot of fine color in a bangle may spread across the entire stone, depending on the fuqi – good fortune – of the owner (Christie's, 1995a). In the past, bangles (and rings) were often made in pairs, in the belief that good things always come in twos (Christie's, 1997).

Figure 6. Circle of Happiness

Figure 6. Circle of Happiness

Believed to date back at least four millennia in China, the jade bangle is both one of the oldest and one of the most important pieces of jewelry in the Chinese culture. This superb fei cui bangle named the "Circle of Happiness" sold for US$3,917,830 at the Sotheby's Hong Kong April 2021 auction, a world record for a fei cui bangle. Image © Sotheby's Hong Kong

Because a single-piece bangle requires a large quantity of fei cui relative to its yield, prices can be quite high, particularly for fine-quality material. The bangle in Figure 6 sold for US$2,576,600 at the Christie's Hong Kong November 1999 auction. Multi-piece bangles are worth less than those fashioned from a single piece, because the former often represent a method of recovering parts of a broken bangle. Mottled material is generally used for carved bangles, as the carving will hide or disguise the imperfections. When a piece is carved from high-quality material, however, it can be a true collector's item (Ng and Root, 1984).

Huaigu (pi)

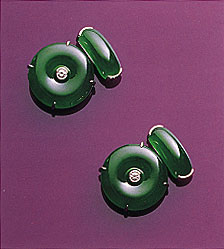

The Chinese symbol of eternity, this is a flat disk with a hole in its center, usually mounted as a pendant or brooch. Ideally, the hole should be one-fifth the diameter of the entire disk and exactly centered. Small pairs are often used in earrings or cufflinks (Figure 27).

Figure 7. These fine matched huaigu (each approximately 19 x 4.5 mm) have been set as cufflinks, with diamonds inserted into their center holes. Each is linked to a saddle top of comparable material. Photo courtesy of and © Christie's Hong Kong and Tino Hammid.

Figure 7. These fine matched huaigu (each approximately 19 x 4.5 mm) have been set as cufflinks, with diamonds inserted into their center holes. Each is linked to a saddle top of comparable material. Photo courtesy of and © Christie's Hong Kong and Tino Hammid.

Saddle Rings (su an)

Carved from a single piece of fei cui, these look like a simple fei cui band onto which a cabochon has been directly cut (Figure 8). Saddle rings allow the most beautiful area to be positioned on top of the ring, while the lower part is relatively hidden, whereas a standard fei cui band should have uniform color all around. Saddle tops are the top piece of a saddle ring, without the band portion (again, see Figure 27).

Figure 8. Note the small patches of a slightly paler color on the shank of one of these "emerald" green saddle rings (21.27 and 21.65 mm, respectively, in longest dimension). Photo courtesy of and © Christie's Hong Kong and Tino Hammid.

Figure 8. Note the small patches of a slightly paler color on the shank of one of these "emerald" green saddle rings (21.27 and 21.65 mm, respectively, in longest dimension). Photo courtesy of and © Christie's Hong Kong and Tino Hammid.

Double Hoop Earrings (lian huan)

These require a large amount of rough relative to their yield, since they are cut from two pieces of the same quality, each of which must produce two hoops. A pair of these earrings (Figure 29) sold for US$1.55 million at Christie's April 29, 1997, Hong Kong sale (Christie's, 1997).

Figure 9. The well-matched hoops and cabochons in these double hoop earrings set with rose-cut diamonds have been dated to the Qing dynasty (1644–1912). They sold for US$1.55 million in 1997. Courtesy of Christie's Hong Kong; photo © Tino Hammid.

Figure 9. The well-matched hoops and cabochons in these double hoop earrings set with rose-cut diamonds have been dated to the Qing dynasty (1644–1912). They sold for US$1.55 million in 1997. Courtesy of Christie's Hong Kong; photo © Tino Hammid.

Carvings

For the most part, the fei cui used in carvings is of lower quality than that used for other cutting styles, but nevertheless there are some spectacular carved fei cui pendants and objets d'art. The intricacy of the design and the skill with which it is executed are significant factors in determining the value of the piece. Carving is certainly one area where the whole equals more than the sum of the parts.

Recut Recovery Potential

As with many other types of gems, the value of poorly cut or damaged pieces is generally based on their recut potential. For example, it might be possible to cut a broken bangle into several cabochons. Thus, the value of the broken bangle would be the value of the cabochons into which it was recut (Ng and Root, 1984). If three cabochons worth $500 each could be cut from the bangle, its value would be about $1,500.

Prices

Next to certain rare colors of diamond (such as blue, pink and red), jade is the world's most expensive gem, with prices far above even ruby and sapphire. The record price for a single piece of fei cui jewelry was set at the November 1997 Christie's Hong Kong sale: Lot 1843, the "Doubly Fortunate" necklace of 27 approximately 15 mm fei cui beads, sold for US$9.3 million (see Figure 4). Indeed, out of the top ten most expensive jewels sold worldwide by Christie's in 1999, five out of ten were fei cui, including three of the top four. These auctions clearly show that fei cui is among the most valuable of all gemstones. The most valuable fei cuis are those of high translucency and rich Cr-green color.

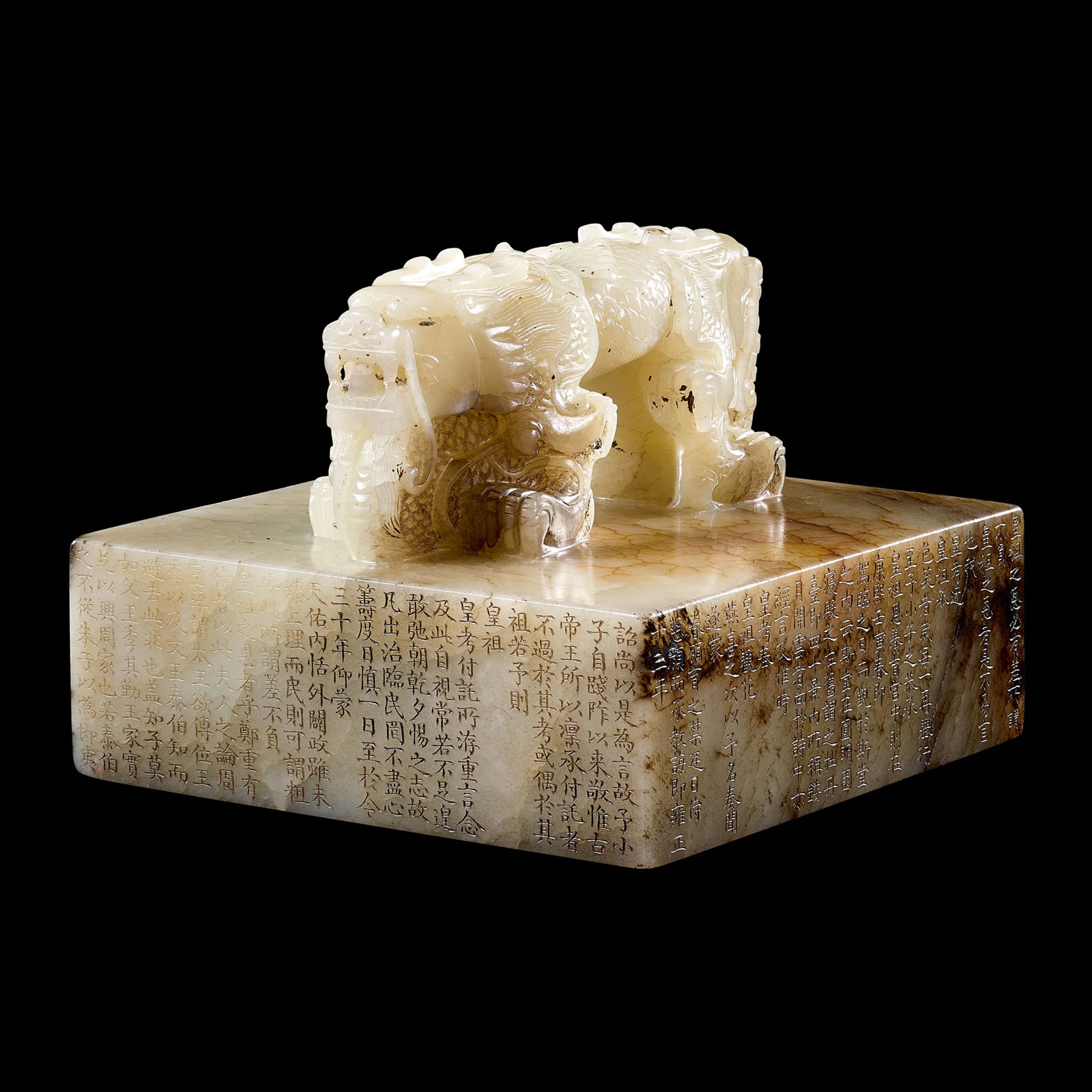

Although Chinese nephrite prices received little attention for many decades, since the rise of China's economy in the 1990's, the original jade has appreciated tremendously. As of 2014, the world auction record for jade is held not by Burmese fei cui, but by Chinese nephrite (see Figure 10).

Figure 10. This large white imperial nephrite Ji’entang seal sold in 2021 for US$18,763,981. Image © Sotheby's

Figure 10. This large white imperial nephrite Ji’entang seal sold in 2021 for US$18,763,981. Image © Sotheby's

Figure 11. The record price at auction for jade was shattered in April 2014 when the Barbara Hutton-Mdivani necklace was purchased by the Cartier Collection for a staggering US$27.44 million. Image © Sotheby's

Figure 11. The record price at auction for jade was shattered in April 2014 when the Barbara Hutton-Mdivani necklace was purchased by the Cartier Collection for a staggering US$27.44 million. Image © Sotheby's

Jade Auction Records

TABLE 2. Jade Auction Records

| Name, weight & description | Sale location | Price realized | Origin | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barbara Hutton-Mdivani Necklace Imperial green fei cui jade necklace featuring 27 round beads from 15.40–19.20 mm. Purchased by the Cartier Collection. World auction record total price for jade |

Sotheby's Hong Kong (Lot 1847) 07 April 2014 |

HK$214,040,000 US$27.44 million |

Myanmar | Sotheby's, 2014 |

| Unnamed Large imperial white jade (nephrite) Ji’entang seal Qing dynasty, Qianlong period, dated to the bingxu year (corresponding to 1766) World auction record total price for nephrite jade |

Sotheby's Hong Kong (Lot 3603) 22 Apr. 2021 |

HK$145,691,000 US$18,763,981 |

China | Sotheby's, 2021 |

| Unnamed Imperial green fei cui jade necklace featuring 23 round beads from 17.35–20.71 mm. Former world auction record total price for fei cui jade |

Tiancheng International Hong Kong (Lot 158) 28 Nov. 2012 |

HK$106.2 million US$13 million |

Myanmar | Tiancheng, 2012 |

| Unnamed Imperial green fei cui jade necklace featuring 10 fei cui cabochons and a matching cabochon ring measuring from 25 × 20 to 14 × 7 mm. World auction record price for a fei cui jade cabochon set |

Tiancheng International Hong Kong (Lot 303) 7 Dec. 2014 |

HK$92,040,000 US$11,824,931 |

Myanmar | Tiancheng, 2014 |

| Doubly Fortunate Necklace Imperial green fei cui jade necklace featuring 27 round beads from 15.09–15.84 mm cut from the Doubly Fortunate fei cui boulder. Former world auction record total price for jade |

Christie's Hong Kong (Lot 1843) 6 Nov. 1997 |

HK$72,620,000 US$9,390,922 |

Myanmar | Christie's, 1997 |

| Unnamed Zitan-mounted imperial inscribed archaic jade bi. Eastern Han dynasty, height 23.8 cm. World auction record price for an archaic nephrite jade |

Sotheby's Hong Kong (Lot 9) 18, 22 April 2021 |

HK$53,771,000 US$6,905,971 |

China | Sotheby's 2021 |

| Unnamed Two cabochons approximately 26.41 × 21.81 × 11.08 mm set in ear studs. World auction record price for a fei cui jade cabochon pair |

Christie's Hong Kong (Lot 2078) 25 Nov. 2014 |

HK$51,640,000 US$6,687,592 |

Myanmar | Christie's 2014 |

| Circle of Happiness 277.673 carat fei cui bangle (approx. 55.21 mm diameter and 10.12 mm thickness) World auction record price for a fei cui bangle |

Sotheby's Hong Kong (Lot 1766) 20 Apr. 2021 |

HK$30,425,000 US$3,917,830 |

Myanmar | Sotheby's, 2021 |

| Unnamed Lavender fei cui jade necklace featuring 35 graduated beads from 15.66 to 14.64 mm. World auction record total price for a lavender fei cui necklace |

Poly Auction, Hong Kong (Lot 2108) 2 Oct. 2018 |

HK$21,240,000 US$2,723,077 |

Myanmar | Poly Auction (2018) |

| Oei Tiong Ham Necklace Green fei cui jade necklace featuring 30 round beads from 13.44–13.32 mm, with a clasp of later date mounted with a star sapphire. Previously owned by one of Oei Tiong Ham's daughters. |

Sotheby's New York (Lot 435) 9 Dec. 2010 |

US$1,986,500 | Myanmar | Sotheby's (2010) |

Figure 11. A then record price at auction for fei cui jade was set in 2012 when this necklace sold for US$13 million.

Figure 11. A then record price at auction for fei cui jade was set in 2012 when this necklace sold for US$13 million.

Image © Tiancheng International

| Property | Fei Cui (Pyroxene Jade) | Nephrite (Amphibole Jade) |

|---|---|---|

| Colors | Various shades of green, lavender, blue, white, colorless, brown, yellow, orange | Near white, various shades of green and brown |

| Composition |

Fei cui is a granular to fibrous rock primarily made up of jadeite (NaAlSi₂O₆), with varying amounts of omphacite [(Ca,Na)(Mg,Fe²⁺,Al)Si₂O₆] and kosmochlor (NaCr³⁺Si₂O₆). Each of these minerals is part of the clinopyroxene mineral group.

|

Nephrite is a fibrous rock composed mainly of the actinolite–tremolite series of the amphibole group [Ca₂(Mg,Fe)₅Si₈O₂₂(OH)₂], where the fibers have grown in a felted (non-parallel) pattern, giving it tremendous toughness.

|

| Hardness (Mohs) | 6.5–7 (single crystals only) | 6–6.5 (single crystals only) |

| Specific gravity | 3.34 (+0.06, –0.09) | 2.95 (+0.15, –0.05) |

| Refractive index | 1.666–1.680 (±0.008); spot RI 1.66; birefringence not measurable on aggregates | 1.606–1.632 (+0.009, –0.006); spot RI 1.61; birefringence not measurable on aggregates |

| Optic character | DR, biaxial (only visible in single crystals; virtually unknown in gems); aggregate polariscope reaction | DR, biaxial (only visible in single crystals; virtually unknown in gems); aggregate polariscope reaction |

| Spectrum | Generally line at 437 nm; Cr-green may have lines at 630, 655, 690 nm | Vague line may be present at 500 nm, but absorption lines are rarely seen. In stones of exceptional gem quality, vague lines in the red part of the spectrum may be seen. |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic; occurs as massive polycrystalline aggregates; single crystals are virtually unknown as cut gems | Monoclinic; occurs as massive polycrystalline aggregates; single crystals are virtually unknown as cut gems |

| Fracture | Granular to splintery | Splintery to granular |

| Pleochroism | None, due to the aggregate nature | None, due to the aggregate nature |

| Phenomena | None | Actinolite may display chatoyancy; strictly speaking this cannot be a nephrite as nephrite by definition has a felted (non-parallel) fibrous structure |

| Handling | No special care needed for untreated fei cui; treated fei cui may be damaged by ultrasonic and/or steam cleaning; solvents, acids | No special care needed for untreated nephrite; treated stones may be damaged by ultrasonic and/or steam cleaning; solvents, acids |

| Enhancements | Most fei cui is wax dipped; some fei cui is dyed and/or bleached and then polymer-impregnated | Some nephrite is dyed and/or bleached and then polymer-impregnated |

| Synthetic available? | Yes, but quite rare in the market | None |

|

Jade – Heaven's Stone More than 2,500 years ago, Gautama Buddha recognized that much of life involves pain and suffering. Consequently, few of us here on Earth have been provided with a glimpse of heaven. Instead, we mostly dwell in hell. But for the Chinese, there is a terrestrial bridge between heaven and hell – jade. While gems such as diamond entered Chinese culture relatively recently, the history of jade (at the time, nephrite or another translucent material used for carving) stretches back nearly ten thousand years. In ancient China, nephrite jade was used for tools, weapons, and ornaments (Hansford, 1950). Jade's antiquity contributes an aura of eternity to this gem. Confucius praised jade as a symbol of righteousness and knowledge.

Yù (玉), the Chinese word for jade, is one of the oldest in the Chinese language; its pictograph is said to have originated in 2950 BC, when the transition from knotted cords to written signs supposedly occurred. The pictograph represents three pieces of jade, pierced and threaded with a string; the dot was added to distinguish it from the pictograph for "ruler" (Goette, n.d.). To the Chinese, jade was traditionally defined by its "virtues," namely a compact, fine texture, tremendous toughness and high hardness, smooth and glossy luster, along with high translucency and the ability to take a high polish (Wang, 1994). But they also ascribe mystical powers to the stone. Particularly popular is the belief that jade can predict the stages of one's life: If a jade ornament appears more brilliant and transparent, it suggests that there is good fortune ahead; if it becomes dull, bad luck is inevitable. Jadeite is a relatively recent entry to the jade family. While some traditionalists feel that it lacks the rich history of nephrite, nevertheless the "emerald" green color of Imperial fei cui is the standard by which all jades – including nephrite – are judged by most Chinese enthusiasts today.

In Hong Kong, jewelry stores are filled almost entirely with fei cui. But if one journeys to mainland China, one can rediscover the ancient Chinese appreciation of jade in the form of nephrite from Xinjiang. This is a stone that does not display the intense color and glossy luster of its fei cui cousin. Instead, its beauty is more sublime. Chinese nephrite has a creamy texture that coaxes, rather than shouts. Picking up a piece, as you caress it, you will quickly understand why this stone was so revered. It truly is the stone of heaven. |

References & Further Reading

- Christie's (1995a) Magnificent Jadeite Jewellery. Catalog for Christie's Hong Kong, May 1, 1995 auction.

- Christie's (1995b) Magnificent Jadeite Jewellery. Catalog for Christie's Hong Kong, October 30, 1995 auction.

- Christie's (1996) Magnificent Jadeite Jewellery. Catalog for Christie's Hong Kong, November 5, 1996 auction.

- Christie's (1997) Magnificent Jadeite Jewellery. Catalog for Christie's Hong Kong, April 29, 1997 auction.

- Christie's (n.d.) 1999: Christie's captures its largest share ever of the jewellery auction market. Christie's press release, 6 pp.

- Damour, A. (1846) Analyse du jade oriental, réunion de cette substance à la trémolite. Annales de Chimie et Physica, Series 3, Vol. 16, pp. 469–474.

- Damour, A. (1863) Notice et analyse sur le jade vert: réunion de cette matière minérale à la famille des wernerites. Comptes Rendus des Séances de l'Académie des Sciences, Vol. 56, pp. 861–865.

- Goette, J. (n.d.) Jade Lore. Reynal & Hitchcock, New York, 321 pp.

- Hacking, I. (2007) The contingencies of ambiguity. Analysis, Vol. 67, No. 4, October, pp. 269–277.

- Hertz, W.A. (1912) Burma Gazetteer: Myitkyina District. Superintendent, Government Printing and Stationery, Rangoon, Volume A, reprinted 1960, 193 pp.

- Ho L.Y. (1996) Jadeite. English ed. Transl. by G.B. Choo, Asiapac, Singapore, 127 pp.

- Hughes, R.W., Galibert, O. et al. (1996–97) Tracing the green line: A journey to Myanmar's jade mines. Jewelers' Circular-Keystone, Vol. 167, No. 11, Nov, pp. 60–65; Vol. 168, No. 1, Jan, pp. 160–166.

- Hughes, R.W. and Ward, F. (1997) Heaven and hell: The quest for jade in Upper Burma. Asia Diamonds, Vol. 1, No. 2, Sept-Oct, pp. 42–53.

- Hughes R.W. (1999) Burma's jade mines: An annotated occidental history. Journal of the Geo-Literary Society, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 15–35.

- Hughes, R.W., Galibert, O. et al. (2000) Burmese jade: The inscrutable gem. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 36, No. 1, pp. 2–26.

- Hughes, R.W. (2000) From Russia with jade. Gemkey Magazine, Vol. 3, No. 1, Nov.–Dec., pp. 58–66.

- Hughes, R.W., Leelawatanasuk, T. et al. (2012) The Chinese box: A Guangzhou jade market puzzle. Journal of the Gemmological Association of Hong Kong, Vol. 33, pp. 50–53.

- Laufer, B. (1912) Jade: A Study in Chinese Archaeology and Religion. Chicago, Field Museum of Natural History, Publication 154, Anthropological Series, Vol. X, 2nd ed. reprinted by Westwood Press, 1946; Dover, 1974, 370 pp.

- Monardes, N. (1569) Dos libros, el uno que trata de todas de las cosas que se traen de nuestras Indias Occidentales, que sirven al uso de la medecina y el otro que trata de la piedra bezaar, y de la yerva escuerçonera. Seville: Hernando Diaz.

- Ng J.Y., Root E. (1984) Jade for You: Value Guide to Fine Jewelry Jade. Jade N Gem Corp. of America, Los Angeles, CA, 107 pp.

- Ou Yang C.M. (1995) Jadeite Appreciation. Cosmos Books Ltd., Hong Kong, 191 pp.[in Chinese]

- Ou Yang C.M. (1999) How to make an appraisal of jadeite. Australian Gemmologist, Vol. 20, No. 5, pp. 188–192.

About the Author

Richard W. Hughes is one of the world’s foremost experts on ruby and sapphire. The author of many books and over 170 articles, his writings and photographs have appeared in a diverse range of publications, and he has received numerous industry awards. Co-winner of the 2004 Edward J. Gübelin Most Valuable Article Award from Gems & Gemology magazine, the following year he was awarded a Richard T. Liddicoat Journalism Award from the American Gem Society. In 2010, he received the Antonio C. Bonanno Award for Excellence in Gemology from the Accredited Gemologists Association. The Association Française de Gemmologie (AFG) in 2013 named Richard as one of the Fifty most important figures that have shaped the history of gems since antiquity. In 2016, Richard was awarded a visiting professorship at Shanghai's Tongji University. 2017 saw the publication of Richard and his wife and daughter's Ruby & Sapphire • A Gemologist's Guide, arguably the most complete book ever published on a single gem species and the culmination of four decades of work in gemology. In 2018, Richard was named Photographer of the Year by the Gem-A, recognizing his photo of a jade-trading market in China, while in 2020, he was elected to the board of directors of the Accredited Gemologists Association and was appointed to the editorial review board of Gems & Gemology and The Australian Gemmologist magazine. In 2022, Richard published Jade • A Gemologist's Guide, while 2024 brought Broken Bangle • The Blunder-Besmirched History of Jade Nomenclature. His jade trilogy was completed in 2025 with his translation of Heinrich Fischer's Nephrite and Jadeite.