An investigation into nephrite and imitation nephrite pebbles purchased in Guangzhou, China's Hualin Street jade market.

Guangzhou Jade Market Puzzle • A Chinese Box

A tale of two stones

For close to eight thousand years, jade (Chinese: yù; 玉) has been treasured by the Chinese. During Neolithic times, nephrite jade was sourced from the now-depleted deposits in the Ningshao area in the Yangtze River Delta (Liangzhu culture 3400–2250 BC) and in an area of the Liaoning province and Inner Mongolia (Hongshan culture 4700–2200 BC). Dushan jade was being mined as early as 6000 BC. In the Yin Ruins of the Shang Dynasty (1600 to 1050 BC) in Anyang, Dushan jade ornaments were unearthed in the tomb of the Shang kings.

Later, a stone called "Kash Tishi" by the Uyghurs was discovered in the White Jade (Yurungkash) and Black Jade (Karakash) Rivers near the town of town of Hetian (aka Hotan, Khotan; Chinese: 和田) in western China's Xinjiang Province (Chinese Turkestan) (Laufer, 1912). From these deposits comes a creamy white to greenish nephrite jade, with the most valuable being pure white. Today, this "mutton fat" jade from Hetian is considered to be the finest in the world, with the highest prices being paid for white stones from the rivers. Material quarried nearby from hard rock mines is much less valuable as it may have hidden cracks and it lacks the natural surface staining of the river stones that is prized by carvers.

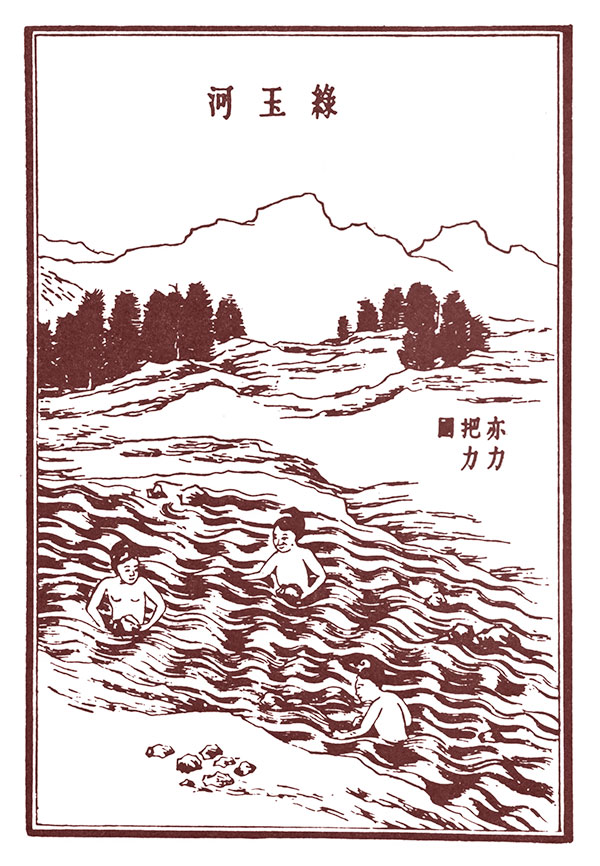

Figure 1. Jade pickers in the Karakash river near Hetian (aka Khotan) in western China's Xinjiang Province. Jade is said to be masculine and thus would be attracted to females. Autumn moonlit nights were thought to be the best time to find jade, as it was believed that the jade would reflect the moonlight. From the T'ien Kung K'ai Wu by Sung Ying-hsing, a 1637 AD Chinese encyclopedia.

Figure 1. Jade pickers in the Karakash river near Hetian (aka Khotan) in western China's Xinjiang Province. Jade is said to be masculine and thus would be attracted to females. Autumn moonlit nights were thought to be the best time to find jade, as it was believed that the jade would reflect the moonlight. From the T'ien Kung K'ai Wu by Sung Ying-hsing, a 1637 AD Chinese encyclopedia.

Much later, in the Qing Dynasty (1644–1914), quantities of a white-to-bright green jade appeared in China, sourced from mines in Upper Burma (Hertz, 1912). A full summary of the Burmese deposits is contained in Hughes et al. (1996–97), Hughes (1999) and Hughes et al. (2000). The Chinese understood this material was different from the Hetian jade, and named the vivid green variety feicui (翡翠) or kingfisher jade, due to its resemblance to the color of the feathers of the kingfisher bird.

By the mid-16th century, the Spanish had spread across much of the New World. In the process they discovered a stone treasured throughout Mesoamerica. Noticing that it was used for pains of the side and lower back, they named it piedra de ijade (stone of the flank of the lower back) (Monardes, 1569). In French this became éjade and then jade, in Italian giade and jade in English. In Dog Latin it was lapis nephriticus (stone good for the kidneys). Mesoamerican jade was the mineral now called jadeite (Hacking, 2007). Hacking continues:

Sweden 1758: Nephrite. Axel von Cronstedt (the geologist who named nickel) renamed lapis nephriticus ‘Nephrit’ in Swedish. That became the German scientific name when he was translated, 1780. It entered A.G. Werner’s classic system (1791). The mineralogists probably, but not certainly, had nephrite samples before then. ‘Nierenstein’ was used in German much earlier, meaning stone good for the kidneys, alongside its other meaning, kidney stone (calculus). In English ‘nephritic stone’ was common.

– Ian Hacking, 2007, "The contingencies of ambiguity"

In 1846, French chemist Alexis Damour did the first chemical analysis of nephrite, finding it to be an amphibole (Damour, 1846). Later, following the British and French armies' 1860 sacking of Beijing's Summer Palace, where many Chinese jade objects were stolen and then made their way to Europe, Damour again analyzed jade. He found the intense green stones to be chemically different from the white-to-pale green nephrite jade, and named the new stone "jadeite" (Damour, 1863; Hacking, 2007).

Figure 2. Map of China showing the location of jade mines and markets. The major source of Chinese nephrite is Hetian (aka Hotan, Khotan) in western China's Xinjiang Province, while jadeite comes from the Hpakan region of Upper Burma.

Figure 2. Map of China showing the location of jade mines and markets. The major source of Chinese nephrite is Hetian (aka Hotan, Khotan) in western China's Xinjiang Province, while jadeite comes from the Hpakan region of Upper Burma.

Map: Richard W. Hughes.

Guangzhou's Hualin Street jade market

In April of 2012, three of the authors (RWH, WM and ACM) paid a visit to Guangzhou's Hualin Street jade market to purchase Chinese nephrite. This market features one of the largest collections of jade vendors in all of China, rivaled only by that located in Ruili on the China-Burma border. But unlike Ruili, where jadeite is the main stock-in-trade, the Guangzhou market also features a healthy section of sellers of the white stone from Xinjiang.

Figure 3. Jade pebbles being examined by a prospective buyer in Guangzhou's Hualin Street jade market. Photo: Richard W. Hughes.

Figure 3. Jade pebbles being examined by a prospective buyer in Guangzhou's Hualin Street jade market. Photo: Richard W. Hughes.

In one small corner of the market, Uighur traders from Xinjiang had lain out a variety of boulders sourced from Xinjiang. Some on blankets, others in suitcases, the impression given was that they were Hetian nephrite.

Figure 4. A Uighur man lays out his wares in Guangzhou's Hualin Street jade market. China's nephrite mines are located near Hetian (aka Khotan), in western China's Xinjiang province. Photo: Richard W. Hughes.

Figure 4. A Uighur man lays out his wares in Guangzhou's Hualin Street jade market. China's nephrite mines are located near Hetian (aka Khotan), in western China's Xinjiang province. Photo: Richard W. Hughes.

Figure 5. A Uighur man showing what looks like Hetian nephrite in Guangzhou's Hualin Street jade market. Photo: Richard W. Hughes.

Figure 5. A Uighur man showing what looks like Hetian nephrite in Guangzhou's Hualin Street jade market. Photo: Richard W. Hughes.

We selected eight white pebbles for purchase from two different vendors. Later, in another corner of the market, we purchased from a shop a further piece carved in a floral motif. The latter was significantly more expensive.

Figure 6. A suitcase of what appears to be Chinese nephrite in Guangzhou's Hualin Street jade market. Like many gem markets, caveat emptor is the norm as imitations abound. Photo: Richard W. Hughes.

Figure 6. A suitcase of what appears to be Chinese nephrite in Guangzhou's Hualin Street jade market. Like many gem markets, caveat emptor is the norm as imitations abound. Photo: Richard W. Hughes.

Figure 7. What appears to be Hetian nephrite in Guangzhou's Hualin Street jade market. Photo: Richard W. Hughes. Click on the photo for a larger image.

Figure 7. What appears to be Hetian nephrite in Guangzhou's Hualin Street jade market. Photo: Richard W. Hughes. Click on the photo for a larger image.

Figure 8. A Uighur woman showing what looks like Hetian nephrite in Guangzhou's Hualin Street jade market. Photo: Richard W. Hughes. Click on the photo for a larger image.

Figure 8. A Uighur woman showing what looks like Hetian nephrite in Guangzhou's Hualin Street jade market. Photo: Richard W. Hughes. Click on the photo for a larger image.

Testing

Following our return to Hong Kong, we decided it would be a good idea to have the pieces checked to ensure they were actually Hetian nephrite and not some imitation, as the prices paid were suspiciously low. Daly Chung of Hong Kong's City Lab performed the initial analyses, determining that the carved piece and two of the pebbles were nephrite, but noticing gas bubbles in several of the others, suspected they were glass imitations. In a desire to determine the exact identity of the imitations, we provided our samples to gemologists at Hong Kong's Gübelin Gem Lab.

Figure 9. Seven pieces of what appears to be Hetian nephrite purchased in Guangzhou's Hualin Street jade market on 2 April 2012 by three of the authors (RWH, WM, ACM). The three pieces in the foreground proved to be genuine nephrite (most likely from Xinjiang), while the four in the background were clever imitations. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul.

Figure 9. Seven pieces of what appears to be Hetian nephrite purchased in Guangzhou's Hualin Street jade market on 2 April 2012 by three of the authors (RWH, WM, ACM). The three pieces in the foreground proved to be genuine nephrite (most likely from Xinjiang), while the four in the background were clever imitations. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul.

Analyses

Initial analyses were carried out by BK, with subsequent analyses by LK and TL, summarized in Table 1. Two pieces of what was believed to be imitation nephrite were selected, with sections sliced off the end of each and a flat facet polished to get an accurate refractive index.

| Property | Nephrite | Imitation Nephrite |

| Refractive Index | approx. 1.61 | 1.508 |

| Specific Gravity | 2.95 | 2.53 |

| Magnification | Secondary iron oxide staining; fibrous inclusions | "Bubble" like feature in one piece; granular aggregate structure; layered structures |

| UV Fluorescence | LW: None; SW: Faint chalky yellow |

Chemical analysis

In order to further determine the nature of the imitation nephrites, x-ray fluorescence (ED-XRF) chemical analyses were performed on two of the specimens (Table 2).

| Element Detected | Specimen 2 Weight % |

| SiO2 | 64.73–71.77 |

| CaO | 10.58–11.70 |

| K2O | 5.73–6.12 |

| Na2O | 2.73–5.02 |

| Al2O3 | 2.56–3.40 |

| ZnO | 2.50–3.46 |

| As2O3 | 0.87–1.13 |

| MgO | 0.72–1.24 |

| TiO2 | 0.41–1.32 |

| Fe2O3 | 0.22–0.27 |

These analyses indicate a silicate of sodium and potassium, with significant traces of copper and zinc, and minor traces of iron, titanium, barium and scandium. Other elements lighter than Na (such as Li, Be, B, F, H, etc.) could not be detected due to the limitations of the ED-XRF technique. Thus the chemical composition was calculated using a semi-quantitative method only. The exact composition may vary.

Figure 10. Bubble-like inclusion just below the surface of an imitation nephrite purchased in Guangzhou's Hualin Street jade market. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul.

Figure 10. Bubble-like inclusion just below the surface of an imitation nephrite purchased in Guangzhou's Hualin Street jade market. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul.

The question of staining

One of the genuine pieces of nephrite purchased in the market had obvious secondary iron-oxide staining. However this is not a reliable indication of genuine origin. In May of 2012, one of the authors (RWH) witnessed such stains being applied to a jade-like material in Ruili's jade market on the China-Burma border (Figure 14).

In his extensive article on Xinjiang jade, Herbert Geiss (2006) described white jade boulders "artificially stained so to give a russet coloured surface skin which enhances their value. According to the 'experts' this process takes about a month and the colour is fixed indelibly and well in the jade matrix."

Figure 11. Chinese white nephrite with iron oxide stains purchased in Guangzhou's Hualin Street jade market. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul.

Figure 11. Chinese white nephrite with iron oxide stains purchased in Guangzhou's Hualin Street jade market. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul.

Figure 12. What appears to be Hetian nephrite seen in Guangzhou's Hualin Street jade market. Some of these feature obvious iron-oxide stains. Photo: Richard W. Hughes.

Figure 12. What appears to be Hetian nephrite seen in Guangzhou's Hualin Street jade market. Some of these feature obvious iron-oxide stains. Photo: Richard W. Hughes.

Figure 13. What appears to be Hetian nephrite in Guangzhou's Hualin Street jade market. The stains on the surfaces of these stones are possibly artificial. Photo: Richard W. Hughes.

Figure 13. What appears to be Hetian nephrite in Guangzhou's Hualin Street jade market. The stains on the surfaces of these stones are possibly artificial. Photo: Richard W. Hughes.

Figure 14. Applying a reddish varnish to the surface of a jade-like material in a workshop in Ruili's jade market (top). Following the treatment, which probably involves firing in an oven, the treated portions assume a reddish color that simulates the natural oxidation staining on the surface of jade boulders.

Figure 14. Applying a reddish varnish to the surface of a jade-like material in a workshop in Ruili's jade market (top). Following the treatment, which probably involves firing in an oven, the treated portions assume a reddish color that simulates the natural oxidation staining on the surface of jade boulders.

Photo: Richard W. Hughes.

Conclusion

Due to the fact that translucent gems such jadeite and nephrite (and materials that resemble them) generally consist of mineral aggregates rather than single crystals, identification by traditional gemological tests is more difficult. The difficulty is compounded when the materials in question are essentially rocks with mixed compositions.

The imitation nephrite pebbles we purchased are a classic example. While it is relatively straightforward to determine what they are not (nephrite or jadeite), it was maddeningly difficult to learn exactly what they are. Like a Chinese box, as we opened one, yet another lay within.

Just prior to going to press, we gave our specimens to Thanong Leelawatanasuk of the Gem & Jewelry Institute of Thailand (GIT). He observed the same gas bubbles in each as Wimon Manorotkul, but most importantly, he discovered references to glass-making in China, including some that are designed to imitate Chinese nephrite. Thanong sent a piece to Thailand's Department of Mineral Resources for X-ray diffraction analysis, where they found the glass to be canasite, with chemical formula of (Na,K)6Ca5Si12O30(OH,F)4. In addition, the raman spectrum showed a match with the mineral frankamenite, the fluorine-rich variety of canasite.

Coupled with the other features found, we believe these unusual white pebbles are clever glass imitations with a composition corresponding to canasite.

|

Jade – Heaven's Stone More than 2,500 years ago, Gautama Buddha recognized that much of life involves pain and suffering. Consequently, few of us here on Earth have been provided with a glimpse of heaven. Instead, we mostly dwell in hell. But for the Chinese, there is a terrestrial bridge between heaven and hell – jade. While gems such as diamond entered Chinese culture relatively recently, the history of jade (at the time, nephrite or another translucent material used for carving) stretches back thousands of years. In ancient China, nephrite jade was used for tools, weapons, and ornaments (Hansford, 1950). Jade's antiquity contributes an aura of eternity to this gem. Confucius praised jade as a symbol of righteousness and knowledge.

Yù (玉), the Chinese word for jade, is one of the oldest in the Chinese language; its pictograph is said to have originated in 2950 BC, when the transition from knotted cords to written signs supposedly occurred. The pictograph represents three pieces of jade, pierced and threaded with a string; the dot was added to distinguish it from the pictograph for "ruler" (Goette, n.d.). To the Chinese, jade was traditionally defined by its "virtues," namely a compact, fine texture, tremendous toughness and high hardness, smooth and glossy luster, along with high translucency and the ability to take a high polish (Wang, 1994). But they also ascribe mystical powers to the stone. Particularly popular is the belief that jade can predict the stages of one's life: If a jade ornament appears more brilliant and transparent, it suggests that there is good fortune ahead; if it becomes dull, bad luck is inevitable. Jadeite is a relatively recent entry to the jade family. While some traditionalists feel that it lacks the rich history of nephrite, nevertheless the "emerald" green color of Imperial jadeite is the standard by which all jades – including nephrite – are judged by most Chinese enthusiasts today.

In Hong Kong, jewelry stores are filled almost entirely with jadeite. But if one journeys to mainland China, one can rediscover the ancient Chinese appreciation of jade in the form of nephrite from Xinjiang. This is a stone that does not display the intense color and glossy luster of its jadeite cousin. Instead, its beauty is more sublime. Chinese nephrite has a creamy texture that coaxes, rather than shouts. Picking up a piece, as you caress it, you will quickly understand why this stone was so revered. It truly is the stone of heaven. |

References & further reading

- Anonymous (n.d.) Brush-rest. www.discoveringbristol.org.uk. Accessed 20 October, 2012.

- Damour, A. (1846) Analyse du jade oriental, réunion de cette substance à la trémolite. Annales de Chimie et Physica, Series 3, Vol. 16, pp. 469–474.

- Damour, A. (1863) Notice et analyse sur le jade vert: réunion de cette matière minérale à la famille des wernerites. Comptes Rendus des Séances de l'Académie des Sciences, Vol. 56, pp. 861–865.

- Geiss, H. (2006) Jade in Khotan. Friends of Jade. October 8, accessed 7 October, 2012.

<https://www.friendsofjade.org/current-article/2006/10/8/jade-in-khotan.html> - Goette, J. (n.d.) Jade Lore. Reynal & Hitchcock, New York, 321 pp.

- Gump, R. (1962) Jade: Stone of Heaven. Doubleday & Co., Garden City, NY, 260 pp.

- Hacking, I. (2007) The contingencies of ambiguity. Analysis, Vol. 67, No. 4, October, pp. 269–277.

- Hansford, S.H. (1950) Chinese Jade Carving, 1st ed. Lund Humphries & Co., London, 145 pp.

- Hertz, W.A. (1912) Burma Gazetteer: Myitkyina District. Superintendent, Government Printing and Stationery, Rangoon, Volume A, reprinted 1960, 193 pp.

- Ho, L.Y. (1996) Jadeite, English ed. Transl. by G.B. Choo, Asiapac, Singapore, 127 pp.

- Hobbs, J.M. (1982) The jade enigma. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 3–19.

- Hughes, R.W. (1999) Burma's jade mines: An annotated occidental history. Journal of the Geo-Literary Society, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 15–35.

- Hughes, R.W., Galibert, O. et al. (1996–97) Tracing the green line: A journey to Myanmar's jade mines. Jewelers' Circular-Keystone, Vol. 167, No. 11, Nov, pp. 60–65; Vol. 168, No. 1, Jan, pp. 160–166.

- Hughes, R.W., Galibert, O., Bosshart, G., Ward, F., Thet Oo, Smith, M., Tay Thye Sun, Harlow, G.E. (2000) Burmese jade: The inscrutable gem. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 36, No. 1, Spring, pp. 2–26.

- Hughes, R.W. and Ward, F. (1997) Heaven and hell: The quest for jade in Upper Burma. Asia Diamonds, Vol. 1, No. 2, Sept-Oct, pp. 42–53.

- Laufer, B. (1912) Jade: A Study in Chinese Archaeology and Religion. Chicago, Field Museum of Natural History, Publication 154, Anthropological Series, Vol. X, 2nd ed. reprinted by Westwood Press, 1946; Dover, 1974, 370 pp.

- Monardes, N. (1569) Dos libros, el uno que trata de todas de las cosas que se traen de nuestras Indias Occidentales, que sirven al uso de la medecina y el otro que trata de la piedra bezaar, y de la yerva escuerçonera. Seville: Hernando Diaz.

- Wang, C. (1994) Essence and nomenclature of jade – A problem revisited. Bulletin of the Friends of Jade, Vol. 8, pp. 55–66.

- Wills, G. (1972) Jade of the East. New York, John Weatherhill, Inc., 1st ed., 196 pp.

- Ying-hsing, S. (1966) T'ien Kung K'ai Wu: Chinese Technology in the Seventeenth Century. Pennsylvania State University Press, 372 pp.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Frederick Desousa of Hong Kong for sample polishing and discussions on the stones, Jack Ogden and Dominick Mok for discussions and examination of specimens, Thailand's Department of Mineral Resources for the x-ray diffraction analysis and Daly Chung, who did the first testing of our specimens to distinguish between the nephrite and imitation nephrite pieces. Also many thanks to John Emmett for discussions on these pieces.

About the authors

Richard W. Hughes is one of the world’s foremost experts on ruby and sapphire. The author of several books and over 170 articles, his writings and photographs have appeared in a diverse range of publications, and he has received numerous industry awards. Co-winner of the 2004 Edward J. Gübelin Most Valuable Article Award from Gems & Gemology magazine, the following year he was awarded a Richard T. Liddicoat Journalism Award from the American Gem Society. In 2010, he received the Antonio C. Bonanno Award for Excellence in Gemology from the Accredited Gemologists Association. The Association Française de Gemmologie (AFG) in 2013 named Richard as one of the Fifty most important figures that have shaped the history of gems since antiquity. In 2016, Richard was awarded a visiting professorship at Shanghai's Tongji University. 2017 saw the publication of Richard and his wife and daughter's Ruby & Sapphire • A Gemologist's Guide, arguably the most complete book ever published on a single gem species and the culmination of nearly four decades of work in gemology. In 2018, Richard was named Photographer of the Year by the Gem-A, recognizing his photo of a jade-trading market in China, while in 2020, he was elected to the board of directors of the Accredited Gemologists Association and was appointed to the editorial review board of Gems & Gemology and The Australian Gemmologist magazine. Richard's latest book, Jade • A Gemologist's Guide, was published in 2022.

Thanong Leelawatanasuk is Chief of the Gem Testing Department at Bangkok's Gem & Jewelry Institute of Thailand.

Wimon Manorotkul has been involved with gems and gemology since 1979, as a lab gemologist, instructor and photographer. She is an Accredited Gemologist from Bangkok's Asian Institute of Gemological Sciences and for many years directed their lab. Wimon also qualified as a Fellow (with honors) of the Gemmological Association of Great Britain. A skilled gem photographer, her images have been featured in books and magazines around the world, particularly Ruby & Sapphire: A Collector's Guide, along with Ruby & Sapphire: A Gemologist's Guide and Inside Out | GEM• ology Through Lotus-Colored Glasses. Wimon not only photographs gems, jewelry and mineral specimens, but is also an expert photomicrographer. In 2013, she founded Lotus Gemology with her husband, Richard Hughes, and daughter, E. Billie Hughes.

Bonita Kwok is a Hong Kong-based gemologist with Gübelin Gem Lab and a Director of the Gemmological Association of Hong Kong.

Dr. Lore Kiefert is Chief Gemologist of the Gübelin Gem Lab. She has co-authored several chapters in textbooks (e.g., Handbook of Raman Spectroscopy), as authored/co-authored close to 100 publications on gems and gemology.

Anne Carroll Marshall was at the time of writing the owner of Anne Carroll Marshall Designs and Romance of the Jewel in Hong Kong and a Director of the Gemmological Association of Hong Kong.

Notes

First published in The Journal of the Gemmological Association of Hong Kong (2012, Vol. 33, pp. 23–26).