Rubies and sapphires occur in a variety of colors. From peacock blue to pigeon's blood red, this article looks at the color types for ruby and sapphire used at Lotus Gemology.

Deconstructing Lotus Color Types

8 April 2015 (updated 19 August 2025)—In recent years, gemological labs have been asked to issue color types on reports. This began with padparadscha sapphire, and has now spread to other varieties, including ruby and blue sapphire.

Lotus Gemology has been involved with historical research on ruby and sapphire for nearly four decades, and coupled with our tremendous experience working with these stones, is well-equipped to define these color types. Our definitions are firmly rooted in both history and direct experience, while at the same time understanding that definitions need to be flexible enough to account for gems from recent sources that were unknown to the ancients. What follows is the Lotus Gemology Guide to Color Types.

Our reports feature color types because of client requests. We understand that customers would like a neutral party to decide whether or not a ruby qualifies as the "pigeon's blood" type, or if a sapphire is "peacock blue."

At the same time, with our many decades of work in the industry, we understand that one cannot dictate to others what is beautiful or attractive; it depends on the individual. Taste is a dish like sashimi, one that should only be served fresh; it's impossible to bottle or clone. For example, the famed American gemologist, George F. Kunz, wrote the following in 1887:

The choicest colors of the sapphire are the cornflower and the velvet-blue.

— G.F. Kunz, 1887, Precious Stones. Appleton's Physical Geography

Note that he made no mention whatsoever of royal blue. Therefore we stress that the final judgement on the merits of a gem should always be made according to what the buyer finds beautiful, not what others believe. In addition, gems must always be judged in person, not via photographs or gemological reports. Photographs and/or words are poor facimilies for direct experience, low-resolution mediums for describing complex and subtle objects. There is no substitute for direct experience.

Important Notes

- The appearance of "color types" is also affected by cutting, clarity, pleochroism and in some cases, fluorescence.

- Each of these color types covers a range, not just a single color.

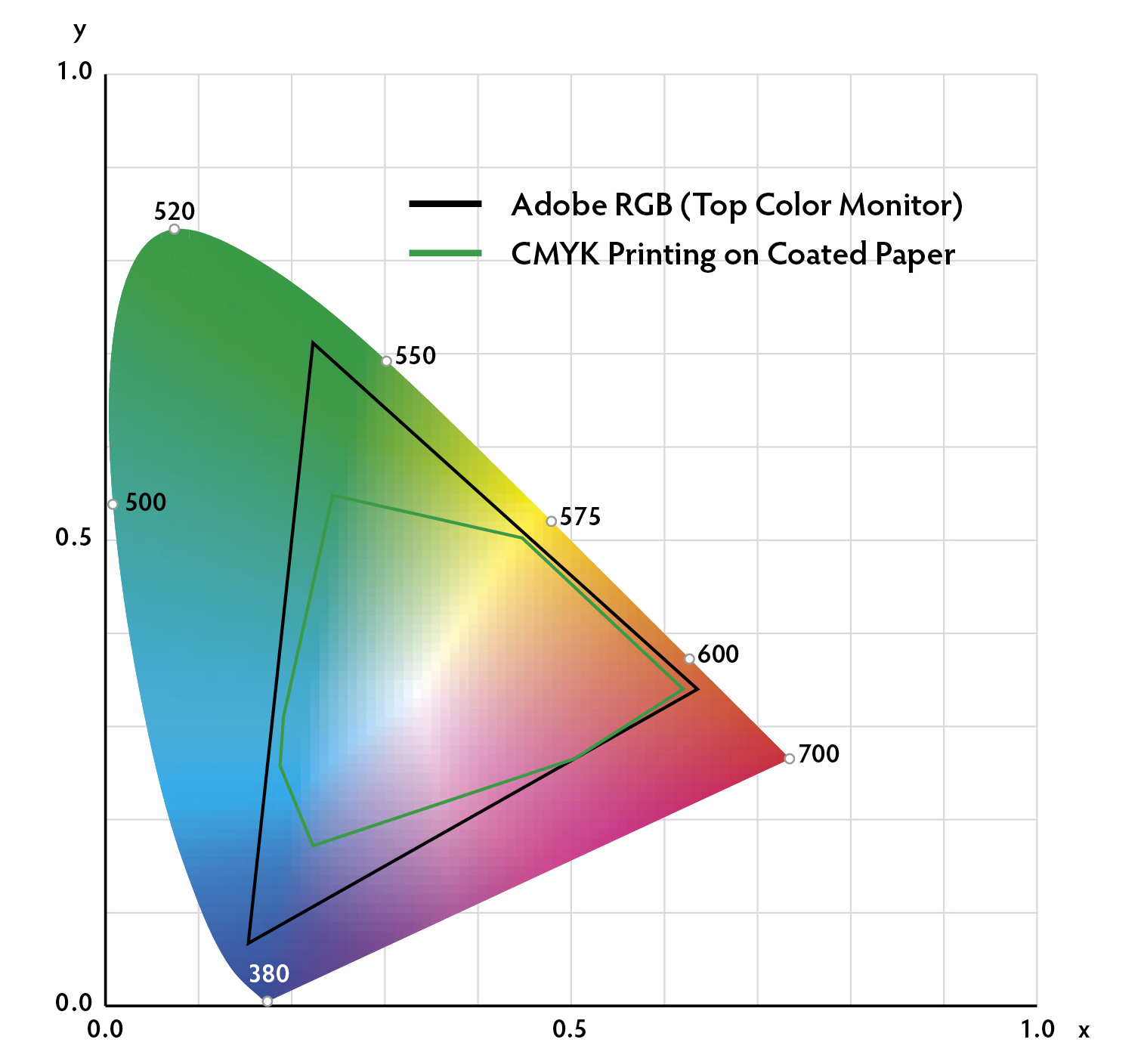

- Certain colors visible to our eyes are not reproducible either in print or on screen. These are termed "out of gamut" colors.

- All colors are affected by the spectral output distribution (SPD) of the light source used to view them.

Lotus Gemology's ruby and sapphire color types.

Lotus Gemology's ruby and sapphire color types.

Ruby & Pink Sapphire

The dividing line between pink sapphire and ruby has long been a point of dispute. For a full discussion of the topic, see Ruby, Pink Sapphire & Padparadscha • Walking the Line.

Pigeon's Blood

According to the most recent research, this color type first appeared in Chinese in an account of the Qing-Burmese gem trade by Liu Kun in 1680 (Sun, 2011). It is said to be either of Chinese or Indian origin, but all agree that it is traditionally the term used to describe the finest colors of ruby. The vast majority of Mogok rubies tend towards purple. It is quite rare to have a stone that is a straight red. This is a glowing color, not unlike that of a red traffic light. The pigeon's blood color is not unique to Mogok; stones of this color are also found at Mong Hsu (Burma), Vietnam, Mozambique, Tanzania and other localities. For more on pigeon's blood, see Red Rain: Mozambique ruby pours into the market.

The pigeon's blood color is sometimes compared to the color of a live pigeon's eye.

The pigeon's blood color is sometimes compared to the color of a live pigeon's eye.

Pigeon's blood ruby.

Pigeon's blood ruby.

Royal Red

A shade darker than pigeon's blood, this color in Burma was traditionally called "rabbit's blood." These rubies tend to have a bit more iron than those of the pigeon's blood type. This cuts the fluorescence and blue transmission, making the stone a darker, pure red. Royal red rubies typically come from Mozambique, Thailand/Cambodia, Kenya and Madagascar.

The royal red color is exemplified by the pillow above. It is a shade darker than pigeon's blood.

The royal red color is exemplified by the pillow above. It is a shade darker than pigeon's blood.

Royal red ruby.

Royal red ruby.

Hot Pink

Depending on one's opinion, this color can fall into the pink sapphire or ruby category. What makes hot pink "hot" is the fact that these gems transmit more of the blue to violet wavelengths. This is due to a relatively low iron content relative to chromium. The result is a bit more bluish red and lots of fluorescence in the red. Gems displaying this color typically come from low iron deposits. Virtually all of the Himalayan deposits (Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nepal, Burma, Vietnam, Yunnan (China) can produce this color, as can some in East Africa (Mozambique, Tanzania).

Hot pink sapphire.

Hot pink sapphire.

Fuchsia

Named after the fuchsia flower, this is an intense purplish red, more red than hot pink. Gems of this color come from a variety of sources, including Burma, Sri Lanka, Mozambique, Vietnam, Afghanistan and Tanzania.

A fuchsia-colored ruby.

A fuchsia-colored ruby.

Blue Sapphire

Cornflower

Fine blue sapphires are often compared to the color of the cornflower, which is shown below. Cornflower blues are found typically found in the same places as pastel sapphires. In terms of tone and saturation, this color lies between the lighter pastel blues and the deeper, more intense peacock and royal blues.

The lovely blue of the cornflower is often used as a reference for fine blue sapphires.

The lovely blue of the cornflower is often used as a reference for fine blue sapphires.

Another shade of cornflower blue, showing that color types cover a range, not just one specific color.

Another shade of cornflower blue, showing that color types cover a range, not just one specific color.

Cornflower blue sapphire.

Cornflower blue sapphire.

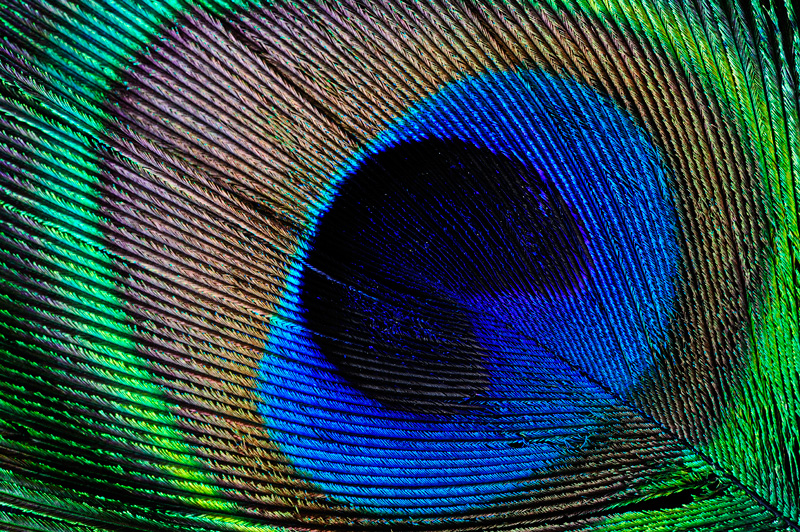

Peacock

In Sri Lanka, some of the finest blue sapphires have been compared with the color of the neck or tail feathers of the peacock. This is an electric blue and can be quite spectacular.

Fine blue sapphires from Sri Lanka are often compared to the color of the peacock's neck or tail feathers.

Fine blue sapphires from Sri Lanka are often compared to the color of the peacock's neck or tail feathers.

Peacock blue sapphire.

Peacock blue sapphire.

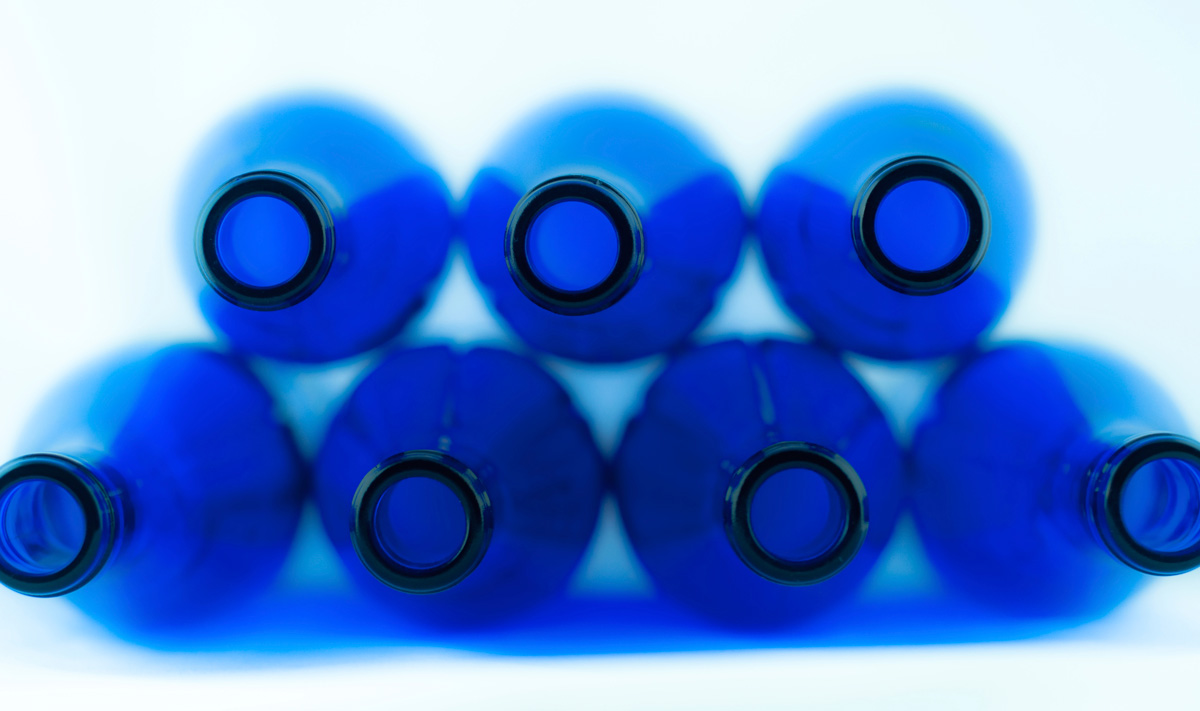

Velvet

Velvet blue sapphires are among the most highly sought after by connoisseurs. Possessing a blue that is almost cobaltian in appearance, these sapphires hail mainly from Kashmir (India), Sri Lanka and Madagascar.

"Milk of Magnesia" blue bottles are often compared with the color of fine "velvet blue" type blue sapphires.

"Milk of Magnesia" blue bottles are often compared with the color of fine "velvet blue" type blue sapphires.

Velvet blue sapphire.

Velvet blue sapphire.

Royal

Of all the colors of ruby and sapphire, the royal blue is the most difficult to show onscreen or in print, as the color is out-of-gamut for both printing and most computer monitors. This is a vivid blue-violet with a deep tone and is epitomized by the fine sapphires from Burma's Mogok Stone Tract. In addition to Myanmar, royal blue sapphires are also found in Madagascar, Tanzania's Tunduru district, and in the smaller sizes, occasionally from Pailin (Cambodia) and Nigeria. Many large tanzanites display a royal blue color.

A fine royal blue sapphire from Myanmar's Mogok Stone Tract. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul.

A fine royal blue sapphire from Myanmar's Mogok Stone Tract. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul.

Indigo

Indigo is a dye traditionally made from the indigo family of plants and is of ancient origin. Today it is seen most often as the blue color of blue jeans. This color type differs from the pure blues of cornflower, peacock, velvet and royal in that it is both deep in tone but slightly lower in saturation. Indigo sapphires are found in many places, particularly deposits derived from basalts. This includes Thailand, Madagascar, Australia, China and Nigeria, to name but a few.

Indigo sapphire.

Indigo sapphire.

Twilight

Resembling the deep blue color of the sky a few minutes after sunset, twilight blue sapphires come from mainly basaltic sources, including Australia, Thailand, Cambodia, Nigeria, China and Vietnam.

Twilight at Australia's Queensland sapphire mines near Rubyvale. Photo: Richard W. Hughes. Click on the image for a larger photo.

Twilight at Australia's Queensland sapphire mines near Rubyvale. Photo: Richard W. Hughes. Click on the image for a larger photo.

Twilight blue sapphire.

Twilight blue sapphire.

Fancy Sapphire

Padparadscha

A sapphire with a color said to be a mixture of a lotus flower and sunset, the lovely padparadscha is the most valuable sapphire next to blue. The original source was Sri Lanka, but fine stones are also found in Madagascar, Tanzania and Vietnam. For more on this topic, see Padparadscha Sapphire & the Ownership of Words.

The padparadscha sapphire displays colors similar to this Sri Lankan sunset. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul.

The padparadscha sapphire displays colors similar to this Sri Lankan sunset. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul.

Padparadscha sapphire.

Padparadscha sapphire.

Lilac

Taking their name from the lilac flower, these sapphires feature a color that varies from pastel lavender through rich violets. Lilac sapphires come to us mainly from Sri Lanka, Burma, Tanzania and Madagascar.

Lilac sapphire.

Lilac sapphire.

Mekong Whisky

This color of yellow sapphire is in high demand in the Thai market and takes its name from the local Mekong Whisky. These gems come mainly from Chanthaburi, Thailand. Heat-treated gems of a similar color come from Sri Lanka.

Whisky-colored yellow sapphires are in great demand in the Thai market.

Whisky-colored yellow sapphires are in great demand in the Thai market.

Mekong whisky yellow sapphire.

Mekong whisky yellow sapphire.

Pastel

Sapphire does not just occur in high saturations, but also delicate pastel shades. Pastel blues come from Sri Lanka, Burma, Kashmir, Madagascar, Tanzania and Montana (USA).

The pastel color range. These colors are characterized by low saturations and light tones.

The pastel color range. These colors are characterized by low saturations and light tones.

Teal

An unusual variety of sapphire is the blue-green teal sapphire, taking its name from the teal duck. These generally come from basalt deposits, such as Australia, Ethiopia, Madagascar, and Thailand.

The vibrant blue-green feathers around the eye of the teak duck are the origin of the teal color.

The vibrant blue-green feathers around the eye of the teak duck are the origin of the teal color.

Teal sapphire.

Teal sapphire.

Understanding color

Understandably, color is the single most important factor when evaluating colored gems. Generally, the more attractive a gem’s color, the higher the value. Bright, rich and intense colors are generally coveted more than those that are too dark or too light. However, there are exceptions, such as the lovely padparadscha sapphire, which is valued for its delicate pastel hues.

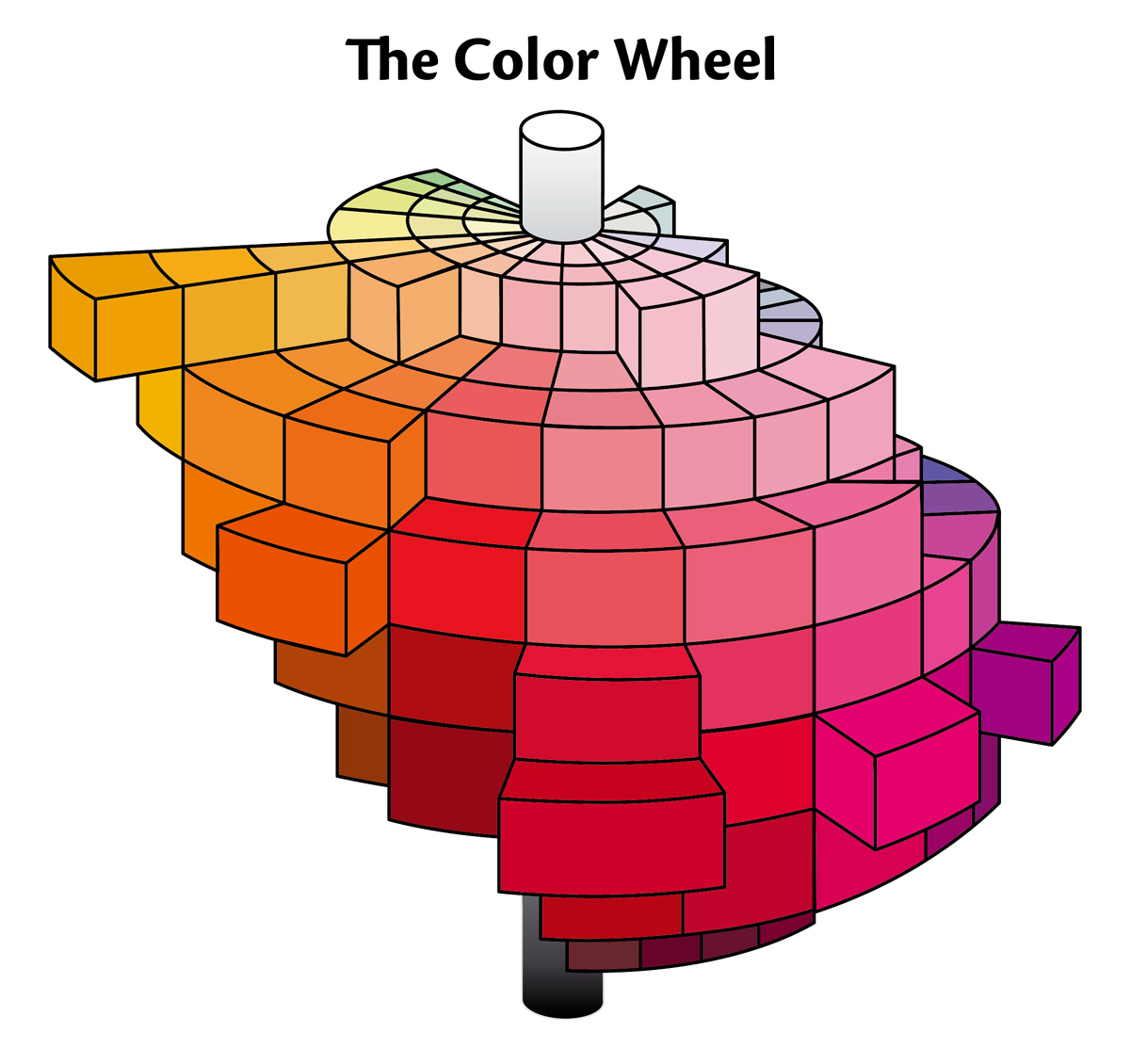

Color is typically described in three dimensions: hue, tone and saturation.

The three dimensions of color. Hues lie around a circle in the horizontal plane. Saturation lies in the horizonal plane, from zero in the center, to maximum at the outside edge. Tone varies in the vertical plane, from the lightest at the top to the darkest at the bottom.

The three dimensions of color. Hues lie around a circle in the horizontal plane. Saturation lies in the horizonal plane, from zero in the center, to maximum at the outside edge. Tone varies in the vertical plane, from the lightest at the top to the darkest at the bottom.

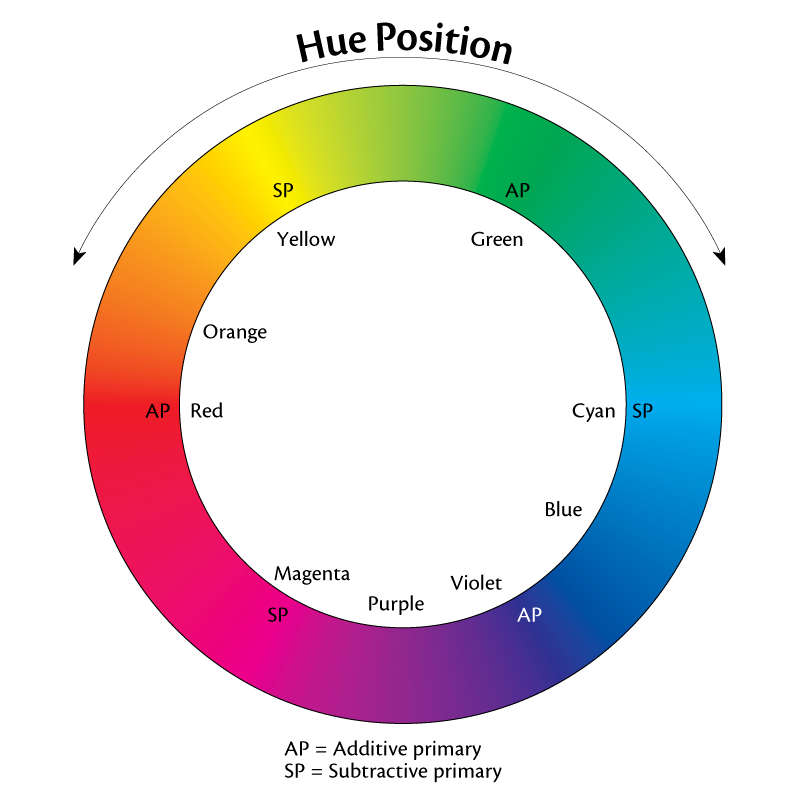

Hue position

The position of a color on a color wheel, i.e., red, orange, yellow, green, blue and violet. Purple is intermediate between red and violet. White and black are totally lacking in hue, and thus achromatic (‘without color’). Brown is not a hue in itself, but covers a range of hues of low saturation (and often high tone). Classic browns fall in the yellow to orange hues.

Generally speaking, gems with hues that most closely resemble the red, green and blue (RGB) sensors in our eyes are most popular. Thus the colored gem trinity, ruby, emerald and sapphire. But there is much about hue that is a personal preference and will depend upon an individual’s particular taste.

The color wheel, showing the various hues arranged around the circle.

The color wheel, showing the various hues arranged around the circle.

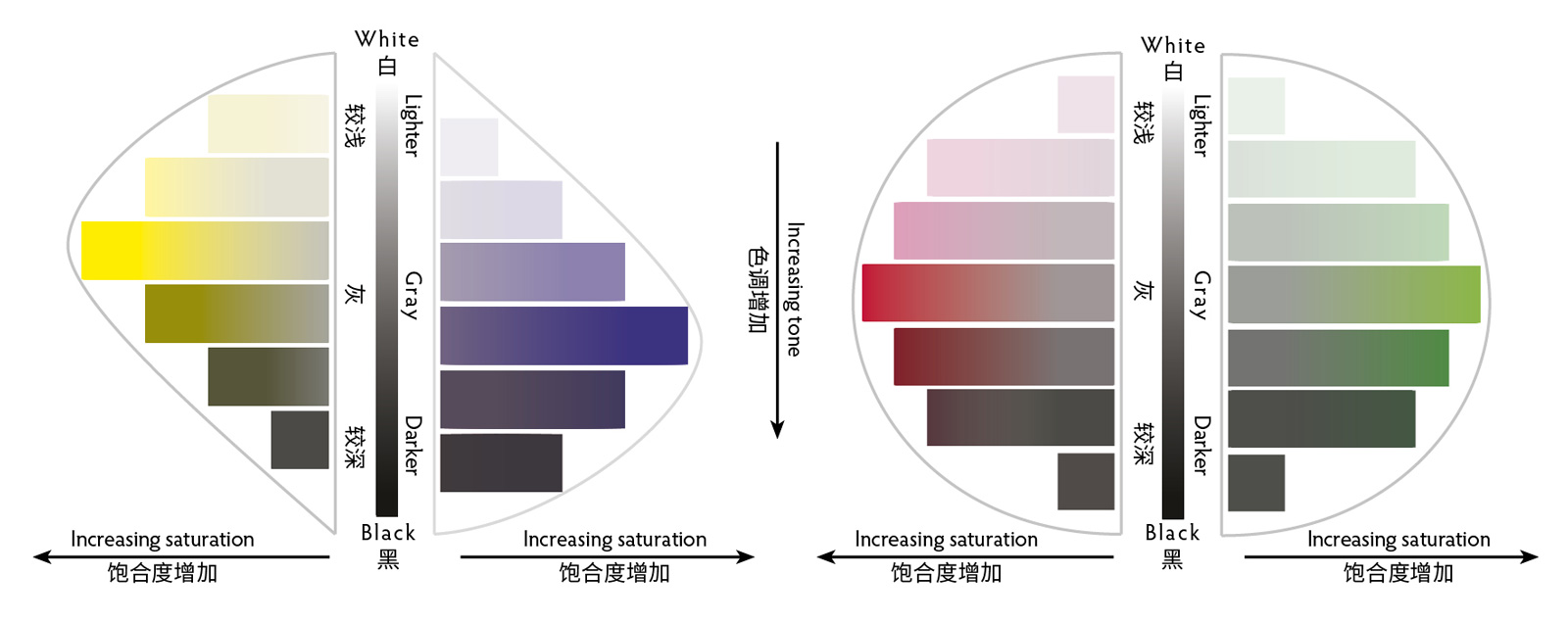

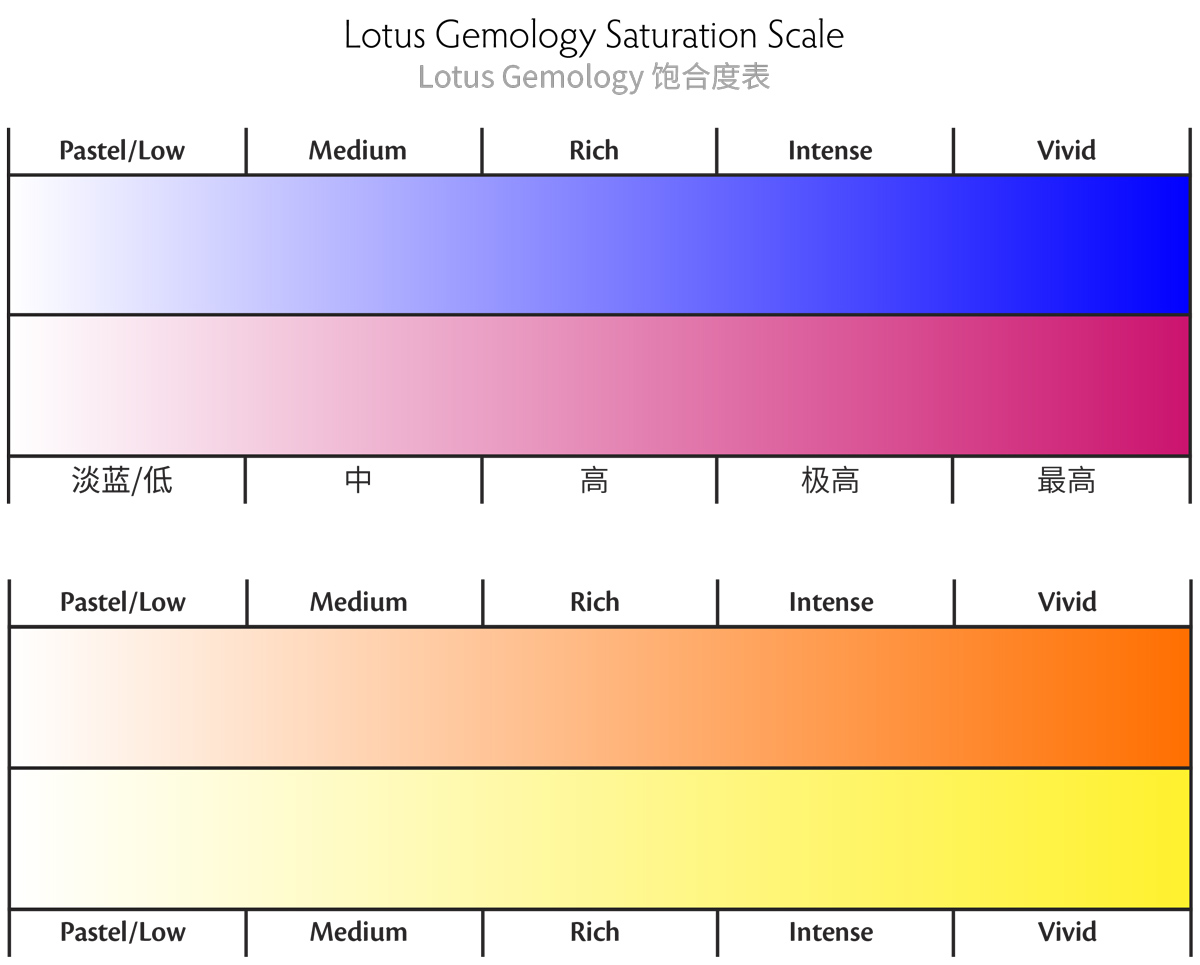

Saturation (intensity)

The richness of a color, or the degree to which a color varies from achromaticity (white and black are the two achromatic colors, each totally lacking in hue). When dealing with gems of the same basic hue position (i.e., rubies, which are all basically red in hue), differences in color quality are mainly related to differences in saturation, because people tend to be more attracted to highly saturate colors. The strong red fluorescence of most rubies is an added boost to saturation, supercharging it past other gems that lack the effect.

Vertical slices through the color sphere demonstrate the relationship between tone and saturation. Yellow at its highest saturation is lighter in tone than violet, while the highest saturations of red and green are equal in tone. Click on the image for a larger version.

Vertical slices through the color sphere demonstrate the relationship between tone and saturation. Yellow at its highest saturation is lighter in tone than violet, while the highest saturations of red and green are equal in tone. Click on the image for a larger version.

On Lotus gemology reports, saturation is broken into five different steps ranging from pastel to vivid.

On Lotus gemology reports, saturation is broken into five different steps ranging from pastel to vivid.

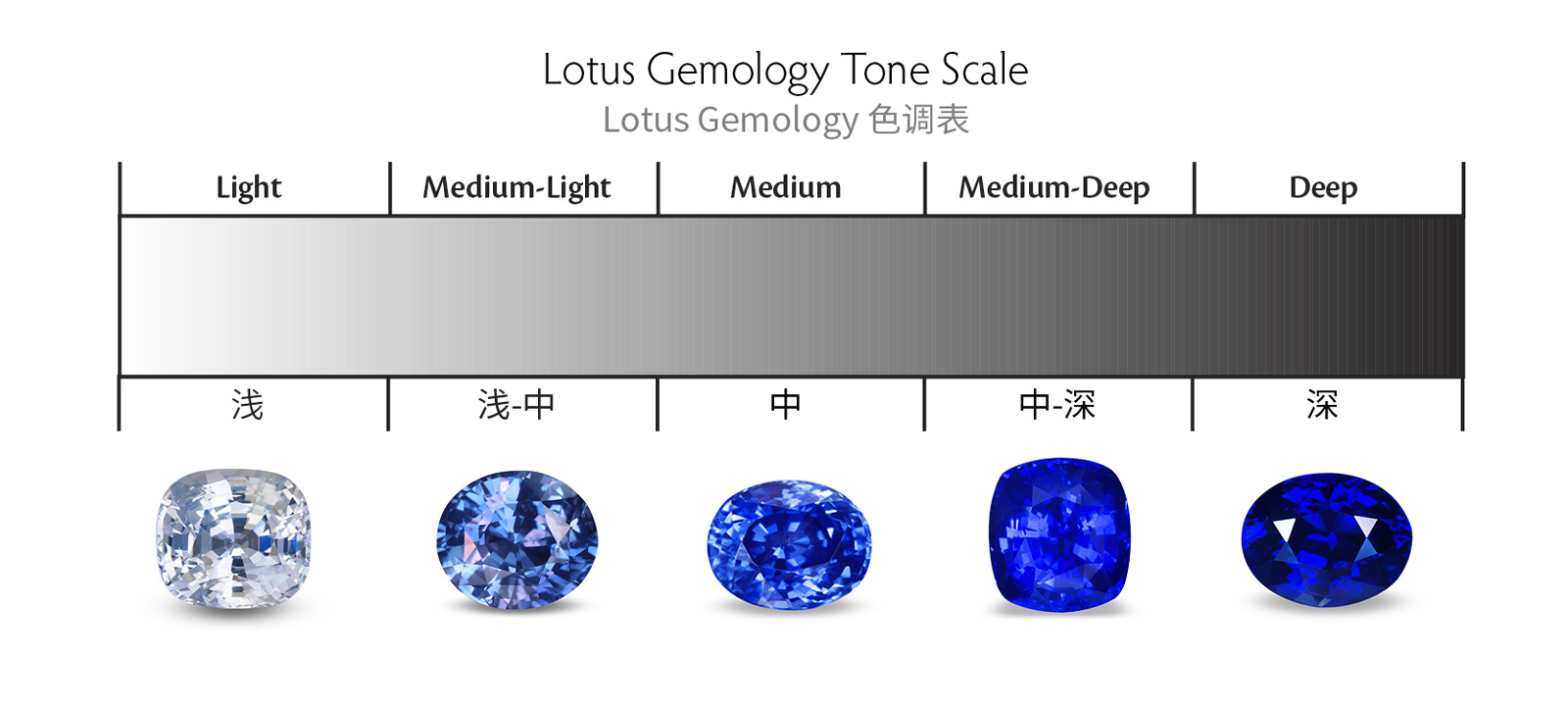

Tone

Tone describes a color's degree of lightness or darkness, as a function of the amount of light absorbed. White would have 0% tone and black would be 100%. At their maximum saturation, some colors are naturally darker than others. For example, a rich violet is darker than even the most highly saturated yellow, while the highest saturations of red and green tend to be of similar tone. Note that as saturation increases, so too does tone (since more light is being absorbed). However, there reaches a point where increases in tone may result in a decrease in saturation, as a color blackens.

When judging the quality of a colored gem, tone is an important consideration. Before buying, it’s always a good idea to consider the lighting conditions under which it will be worn. Look for stones that look good even under the low lighting conditions you find in the evening or in a restaurant, for these are typically the conditions under which fine gems are worn and viewed. Also view gems at arm’s length and look for those that are attractive even at a distance. Exceptional gems tend to look great under all lighting conditions and viewing distances.

Although specific colors are more popular than others, personal preferences are also important. The colors seen should ideally remain attractive regardless of prevailing light conditions, whether viewed indoors, outdoors, by day or by night.

Lotus Gemology reports use a five-step tonal scale. Click on the image for a larger version.

Lotus Gemology reports use a five-step tonal scale. Click on the image for a larger version.

The C.I.E. chromaticity diagram is used to specify the exact position of all colors visible to the human eye. Note that a computer monitor (represented by Adobe RGB) can only display some of these colors. The colors that can be printed using the standard CMYK printing process is even further restricted. Many rubies and sapphires feature colors outside of both of these “gamuts.” Thus judgment must be made by personal examination, rather than via photos. Click on the image for a larger version.

The C.I.E. chromaticity diagram is used to specify the exact position of all colors visible to the human eye. Note that a computer monitor (represented by Adobe RGB) can only display some of these colors. The colors that can be printed using the standard CMYK printing process is even further restricted. Many rubies and sapphires feature colors outside of both of these “gamuts.” Thus judgment must be made by personal examination, rather than via photos. Click on the image for a larger version.

|

Traditional Burmese Color and Texture Terms (after Maung Tun Oo, 2010) Traditional Burmese color terms

Burmese ruby texture terms

|

Acknowledgements

We thank Hpone-Phyo Kan-Nyunt and U Maung Tun Oo for help with the traditional Burmese color and texture terms.

References & further reading

- Brown, J.C. (1936) India’s Mineral Wealth. Calcutta, Oxford University Press, 1st ed., 335 pp.; RWHL.

- Halford-Watkins, J.F. (2012) The Book of Ruby and Sapphire. Hong Kong, RWH Publishing, [edited by Richard W. Hughes from a 1934 manuscript], 434 pp.; RWHL*.

- Hertz, B. (1839) A Catalogue of the Collection of Pearls and Precious Stones Formed by Henry Philip Hope, Esq. London, William Clowes and Sons, 112 pp., 42 plates; RWHL*.

- Hughes, R.W. (1987) Ruby or pink sapphire? A lesson from the past. Gemological Digest, Vol. 1, No. 1, p. 3, RWHL*.

- Hughes, R.W. (1990) Corundum. Butterworths Gem Books, Northants, UK, Butterworth-Heinemann, 314 pp., RWHL*.

- Hughes, R.W. (1996) Pigeon’s blood. Momentum, Vol. 4, No. 13, Dec. 1996-Feb. 1997, pp. 18–21; RWHL*

- Hughes, R.W. (1997) Ruby & Sapphire. Boulder, CO, RWH Publishing, 512 pp.; RWHL*.

- Hughes, R.W. (2002) Walking the line in ruby & sapphire. The Guide, Vol. 21, Issue 4, Part 1, July–Aug., pp. 4–8; RWHL*.

- Hughes, R.W. (2015) Red Rain: Mozmabique ruby pours into the market.

- Maung Tun Oo (2010) World Famous Ruby Land. Yangon, [in Burmese and English], RWHL*.

- Prinsep, J. and Kalíkishen, R. (1832) Oriental accounts of the precious minerals. Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Vol. 1, pp. 353–363; RWHL*.

- Rees, A. (1819) Gems. In The Cyclopædia; or Universal Disctionary of Arts, Sciences, and Literature, London, Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, & Brown, 39 Vols., Vol. 15, see Gems; RWHL.

- Shastri, J.L., ed. (1978) Garuda Purana. English translation 1978, Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass, Vol. 12, Part 1, see pp. 224–246; RWHL*.

- Smith, H.G. (1896) Gems and Precious Stones. Sydney, Charles Potter, 87 pp.; RWHL.

- Streeter, E.W. (1892) Precious Stones and Gems. London, Bell, 5th edition, 355 pp.; RWHL*.

- Sun, L. (2011) From baoshi to feicui: Qing-Burmese gem trade, C. 1644–1800 In Chinese Circulations: Capital, Commodities, and Networks in Southeast Asia, Edited by Tagliacozzo, E. and Chang, W.-C., Duke University Press, pp. 203–221; RWHL*.

- Tagore, S.M. (1879, 1881) Mani-Málá, or a Treatise on Gems. Calcutta, I.C. Bose & Co., 2 Vols., 1046 pp.; RWHL*.

- Tennent, J.E. (1859) Ceylon: An Account of the Island, Physical, Historical and Topographical. London, Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts, 2 Vols., 702 pp.; RWHL.