The history of glass-infilling in blue sapphire, along with a description of the latest treatment generation developed in Chanthaburi, Thailand.

| To download a PDF copy of this paper, click on the icon at right |  |

Introduction

In September of 2007, five faceted stones and a few rough samples were submitted to the Bangkok lab of the Gem and Jewelry Institute of Thailand (GIT) by a gem treater who informed the lab that they represented a new type of treatment. The name applied to this treatment at the time was Super Diffusion Tanusorn, named after Tanusorn Lethaisong, the Chanthaburi, Thailand treater who developed it (GIT, 2007). In reality this treatment did not involve diffusion, but was simply an infilling of cobalt-colored glass into a highly fractured corundum, dying it blue. The starting material for this treatment was said to be low-grade near-colorless corundum from Madagascar or Sri Lanka (Abduriyim, 2007). Initial finished samples were of low quality, being semi-translucent.

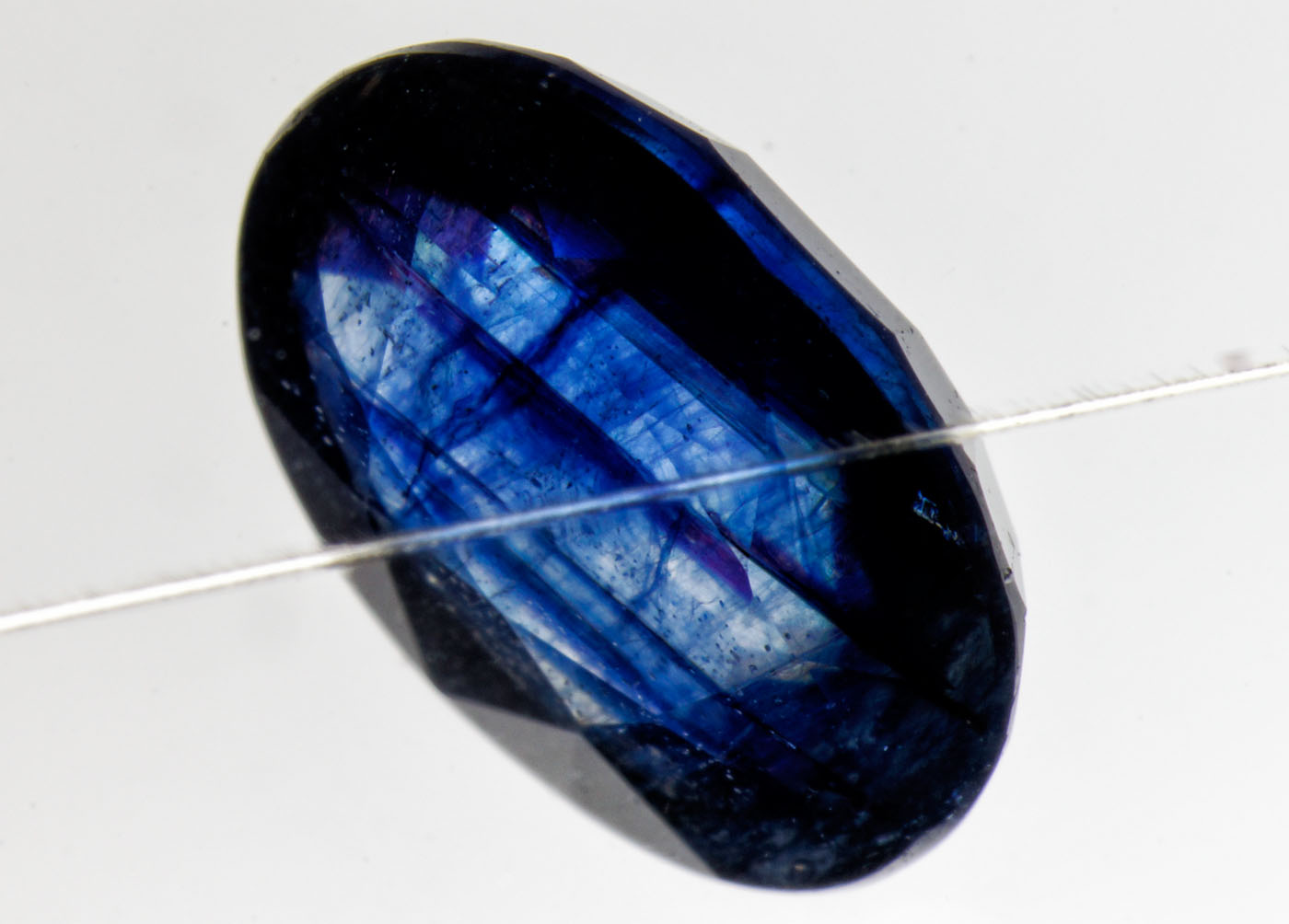

Five years later, in May of 2012, GIT’s lab received two unusual blue stones for identification (Leelawatanasuk, 2012). One was a 6.62-ct cabochon, with the other being a 7.57-ct stone that was faceted on the crown and cabochon cut on the pavilion (Figure 1). It was said that the stones were blue sapphires heated in the conventional fashion.

Figure 1. Two blue stones weighing 7.57 ct (left) and 6.62 ct (right) submitted to GIT for testing in May 2012.

Figure 1. Two blue stones weighing 7.57 ct (left) and 6.62 ct (right) submitted to GIT for testing in May 2012.

Photo: Warinthip Krajae-Jan

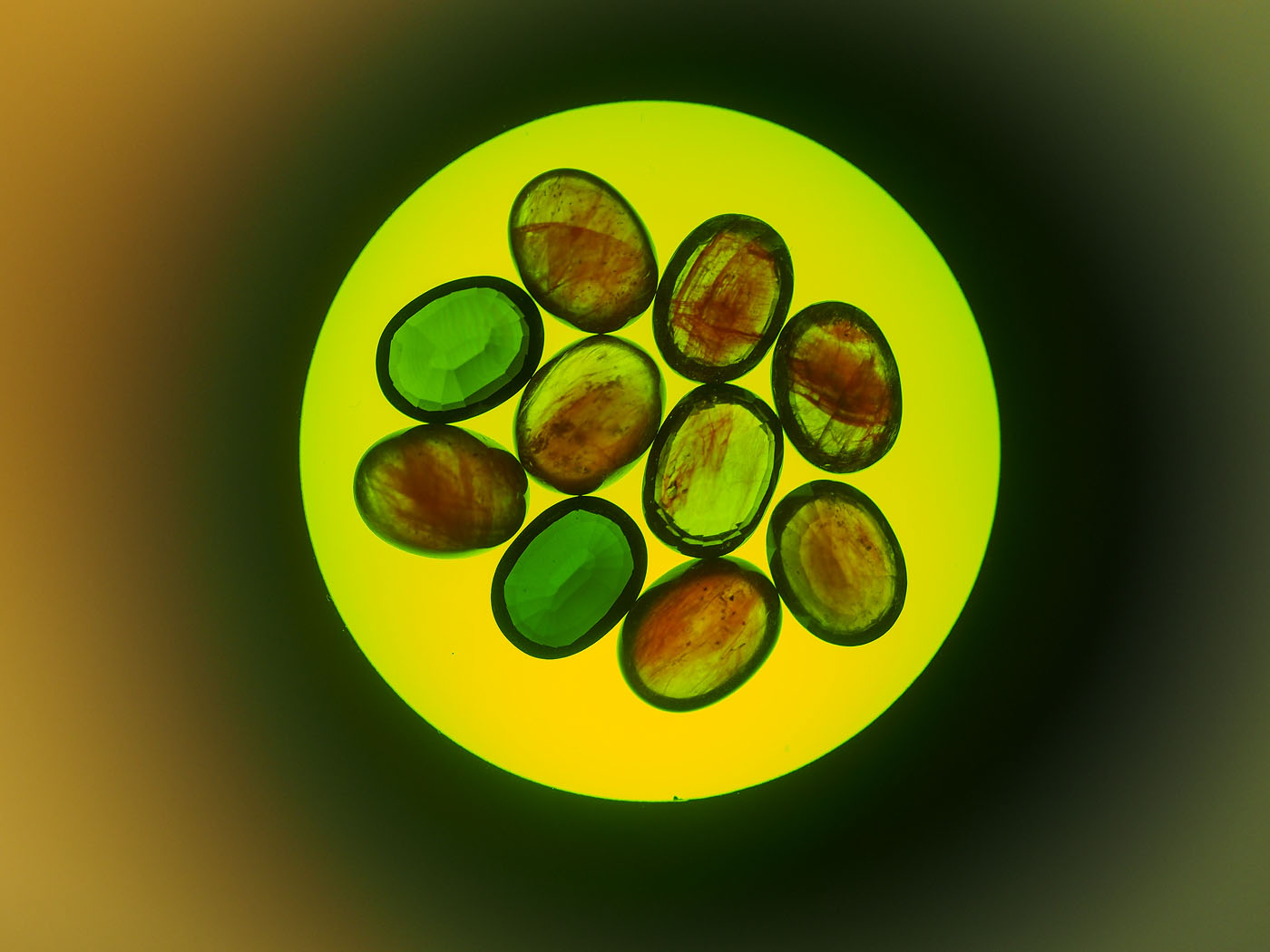

Figure 2. Two first-generation cobalt-doped glass-filled sapphires (top row; 3.49 & 3.37 ct), along with eight latest-generation cobalt-doped glass-filled sapphires ranging from 1.50–2.25 ct each that were tested as part of this study. Note the far lower clarity of the first-generation stones. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Figure 2. Two first-generation cobalt-doped glass-filled sapphires (top row; 3.49 & 3.37 ct), along with eight latest-generation cobalt-doped glass-filled sapphires ranging from 1.50–2.25 ct each that were tested as part of this study. Note the far lower clarity of the first-generation stones. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Refractive index and specific gravity values were typical for sapphire within the degree of error. However microscopic examination revealed features that were decidedly not natural. While some features (included crystals, lamellar twinning) were typical of natural sapphire, the stones were riddled with fissures filled with a rich blue substance that stood out strongly against the otherwise near colorless sapphire. Indeed, so strong was the blue substance in the fissures that it strongly colored what would otherwise be near colorless sapphires. In effect, the stones were dyed blue.

Since that time, a number of additional pieces have been examined. Effectively these stones represent a refinement of the original Tanusorn treatment.

What follows is a discussion of the general properties and key identifying features of this new type of treated sapphire.

General Properties

The gemological properties for these stones are generally consistent with natural sapphire, with a few important exceptions. Specific gravity values were slightly elevated in some specimens. But more importantly, all of the stones tested showed a strong red to orange-red when viewed with the Chelsea filter. Both natural and synthetic blue sapphires show no red.

In addition, examination with the dichroscope revealed a lack of pleochroism. This is because the rich color of the stones comes from the cobalt colorant in the glass, rather than from the sapphire structure itself.

Together, the Chelsea filter reaction and lack of pleochroism allow easy separation from both natural and synthetic sapphire, including sapphire enhanced by both standard heating and titanium bulk diffusion.

Figure 3. When viewed through the Chelsea filter, the new-generation cobalt-glass filled sapphires showed a strong red reaction. As the above photo demonstrates, the red color is concentrated in the fissures filled with the cobalt-colored glass. Natural, heat-treated, Ti-diffusion treated and synthetic sapphires will not show red through the Chelsea filter. The two stones in the above photo without red are Verneuil synthetic sapphires. Photo: Richard Hughes

Figure 3. When viewed through the Chelsea filter, the new-generation cobalt-glass filled sapphires showed a strong red reaction. As the above photo demonstrates, the red color is concentrated in the fissures filled with the cobalt-colored glass. Natural, heat-treated, Ti-diffusion treated and synthetic sapphires will not show red through the Chelsea filter. The two stones in the above photo without red are Verneuil synthetic sapphires. Photo: Richard Hughes

Figure 4. Testing with a London dichroscope revealed no pleochroism when inclined to the c-axis, as shown in the photo above. Natural, heat-treated, Ti-diffusion treated and synthetic sapphires will show obvious pleochroism in stones with this depth of color. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Figure 4. Testing with a London dichroscope revealed no pleochroism when inclined to the c-axis, as shown in the photo above. Natural, heat-treated, Ti-diffusion treated and synthetic sapphires will show obvious pleochroism in stones with this depth of color. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

| Property | Results: Old generation1 | Results: New generation2 |

|---|---|---|

| Refractive Index | 1.762–1.770 (0.008); uniaxial (–) | 1.762–1.770 (0.008); uniaxial (–) |

| Polariscope Reaction | None; semi-translucent | Doubly refractive; most stones too heavily twinned to resolve uniaxial figure |

| Specific Gravity (Hydrostatic) | 3.95–3.96 ±0.063 | 4.05 ±0.123 |

| UV Fluorescence | Weak red-orange in LW | Inert to weak red-orange in both LW & SW; red-orange fluorescence concentrated in the fissures |

| Visible Spectrum | Weak Fe spectrum from the sapphire, with lines at 450, 460, 471 nm; Co-glass spectrum from the glass, with broad absorption in the yellow at 591 and less at 530 and 625 nm | Weak Fe spectrum from the sapphire, with lines at 450, 460, 471 nm; Co-glass spectrum from the glass, with broad absorption in the yellow at 591 and less at 530 and 625 nm |

| Pleochroism | None visible; this is because the underlying sapphire has little color and thus makes an excellent field-test | None visible; this is because the underlying sapphire has little color and thus makes an excellent field-test |

| Chelsea Filter | Strong red to orange red; this test can be used to easily separate cobalt-doped glass-filled sapphires from both natural and synthetic sapphires | Strong red to orange-red; this test can be used to easily separate cobalt-doped glass-filled sapphires from both natural and synthetic sapphires |

| Inclusions | Natural inclusions such as crystals, healed fissures and polysynthetic twinning in the sapphire portion; pools of deep blue glass in surface-reaching cavities and fissures | Natural inclusions such as crystals and polysynthetic twinning in the sapphire portion; flash effect in the fissures from the glass filler; color concentrations in the glass filler; undercutting of the glass filler at the surface; flattened gas bubbles trapped in the glass filler |

| 1 Based on the testing of two stones weighing 3.49 and 3.36 ct, purchased by GIT in 2007. 2 Based on the testing of eight stones ranging from 1.50–2.25 ct, purchased by RWH in Chanthaburi in December 2012. 3 Based on a potential error of ±0.01 ct in both the air and water weighing. |

||

Microscopic Features

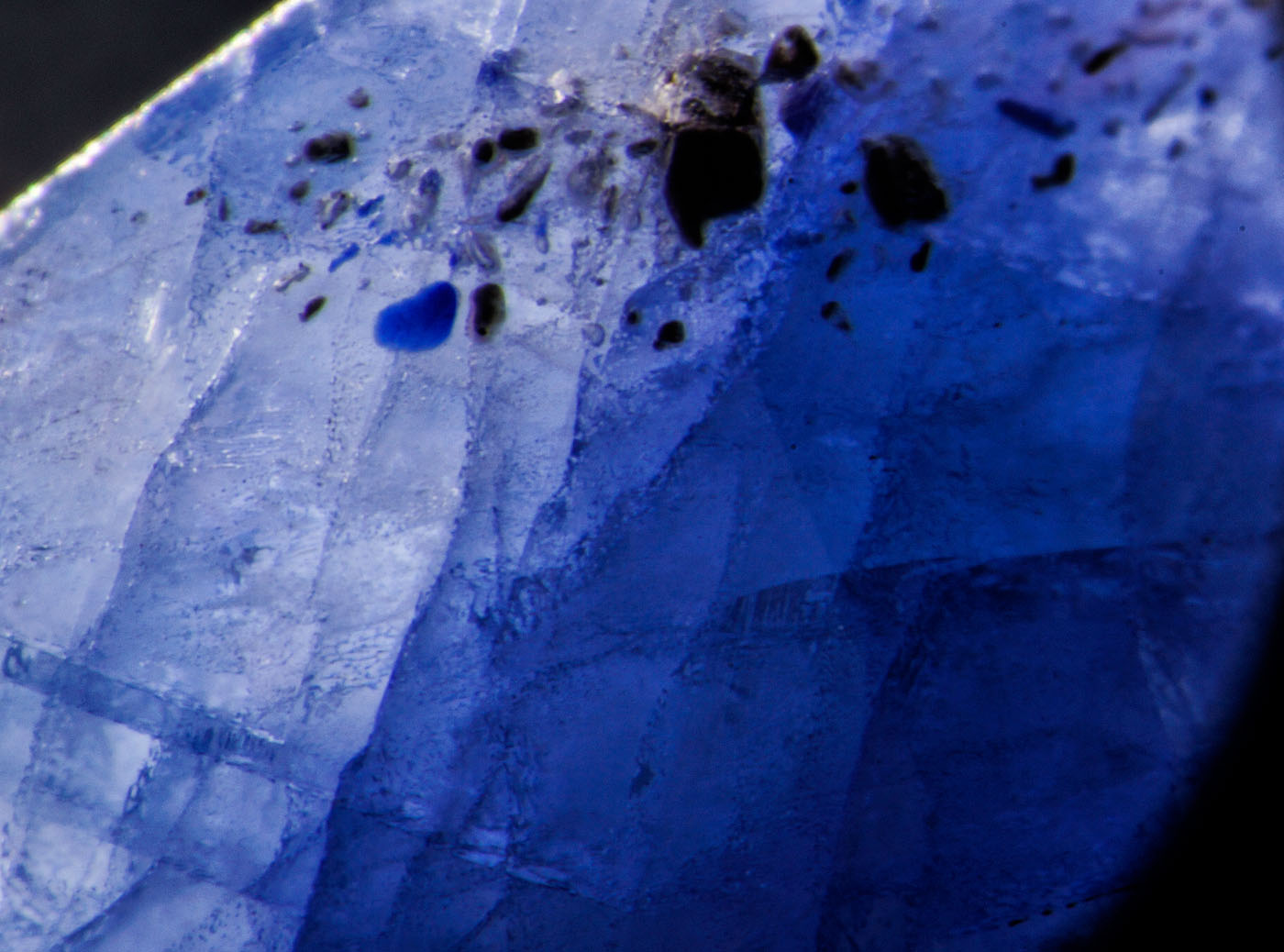

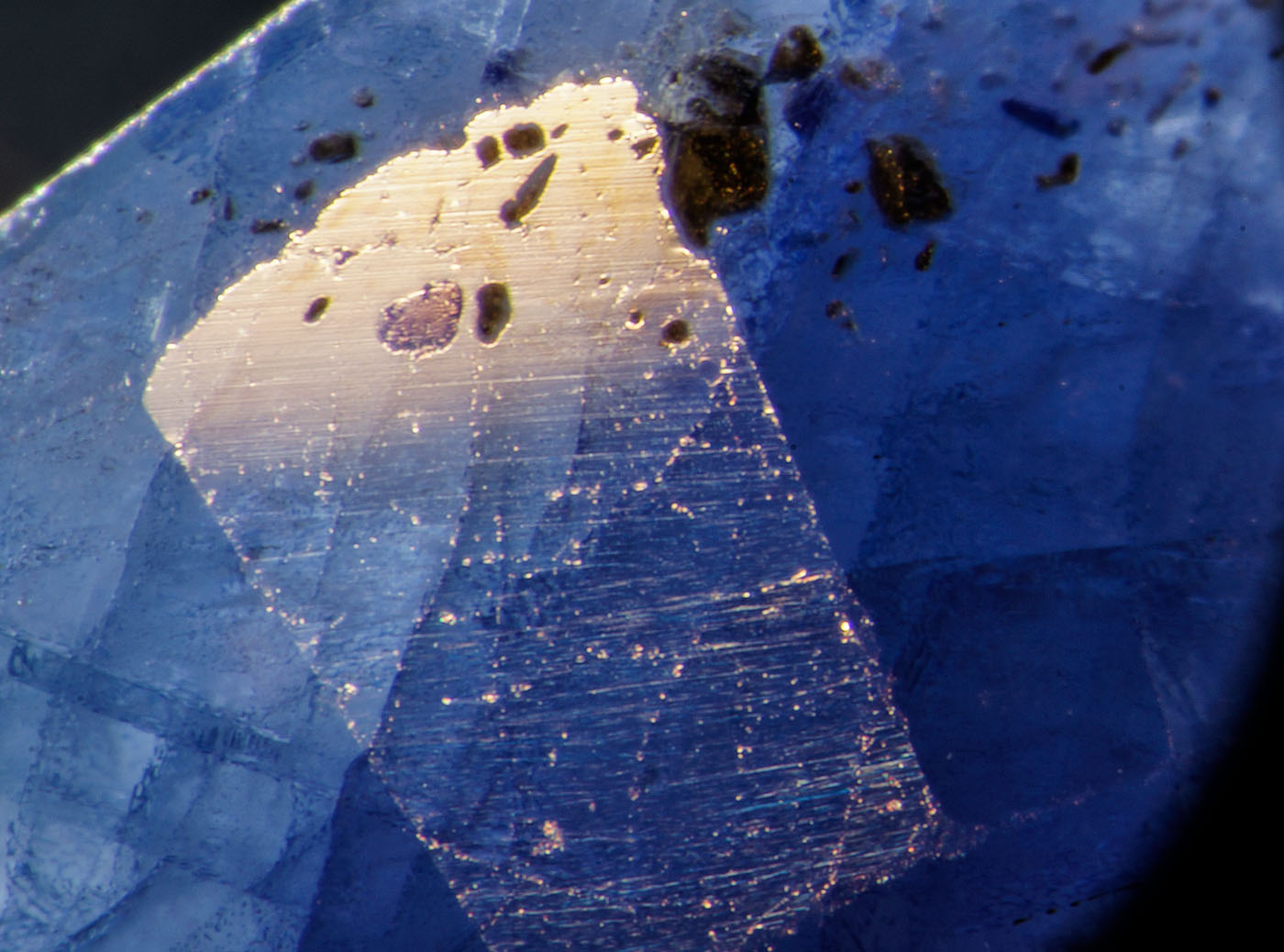

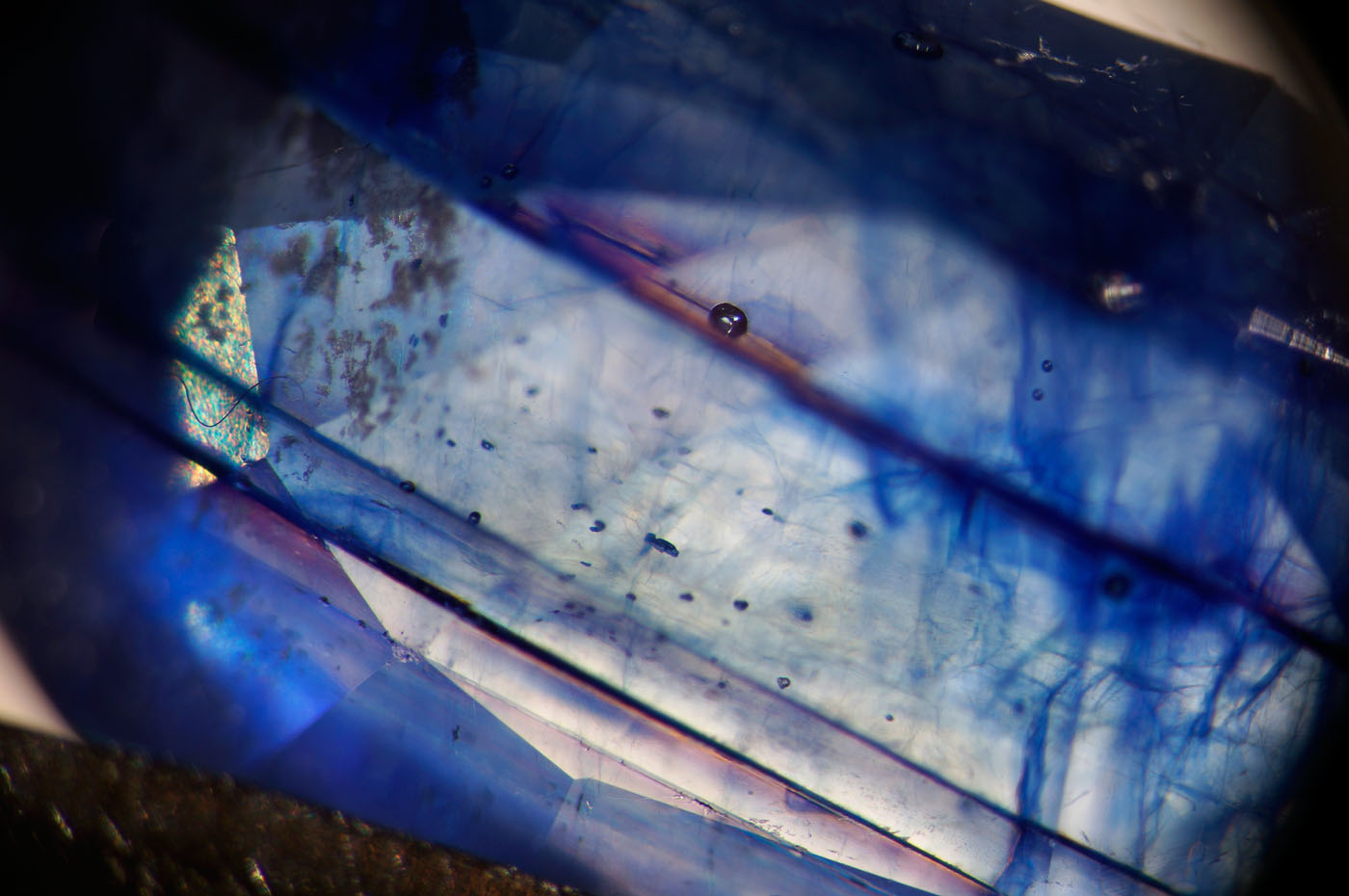

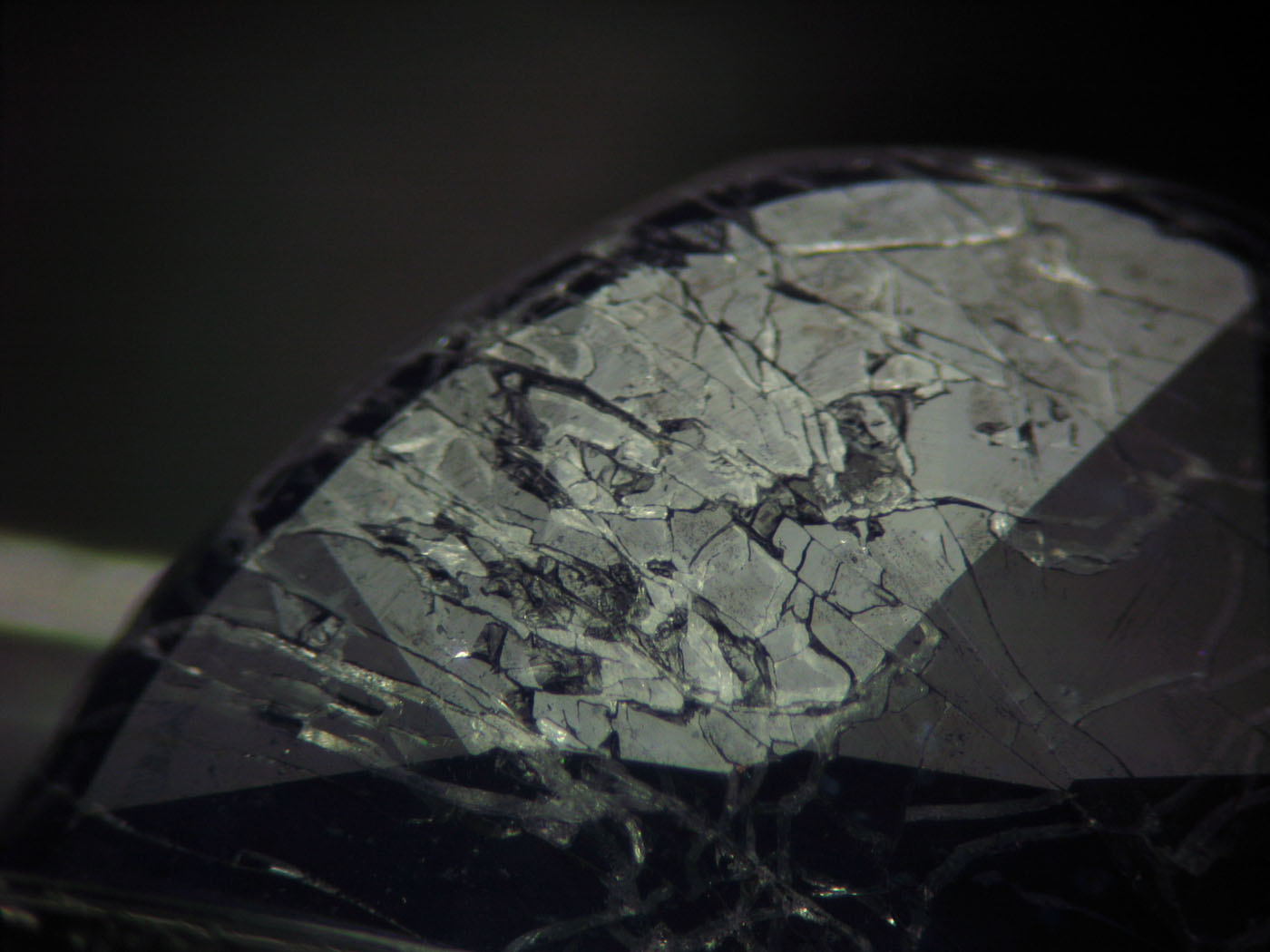

Microscopic examination is also important for the identification of this treatment (Figures 5–12). The first generation Tanusorn stones (Figures 5–6) were heavily included, so much so that they were only semi-translucent. Stones were riddled with polysynthetic twinning and secondary healed fissures. Near the surface, cavities were filled with a rich blue cobalt-doped glass, while in other places the blue glass penetrated surface openings, such as fingerprints.

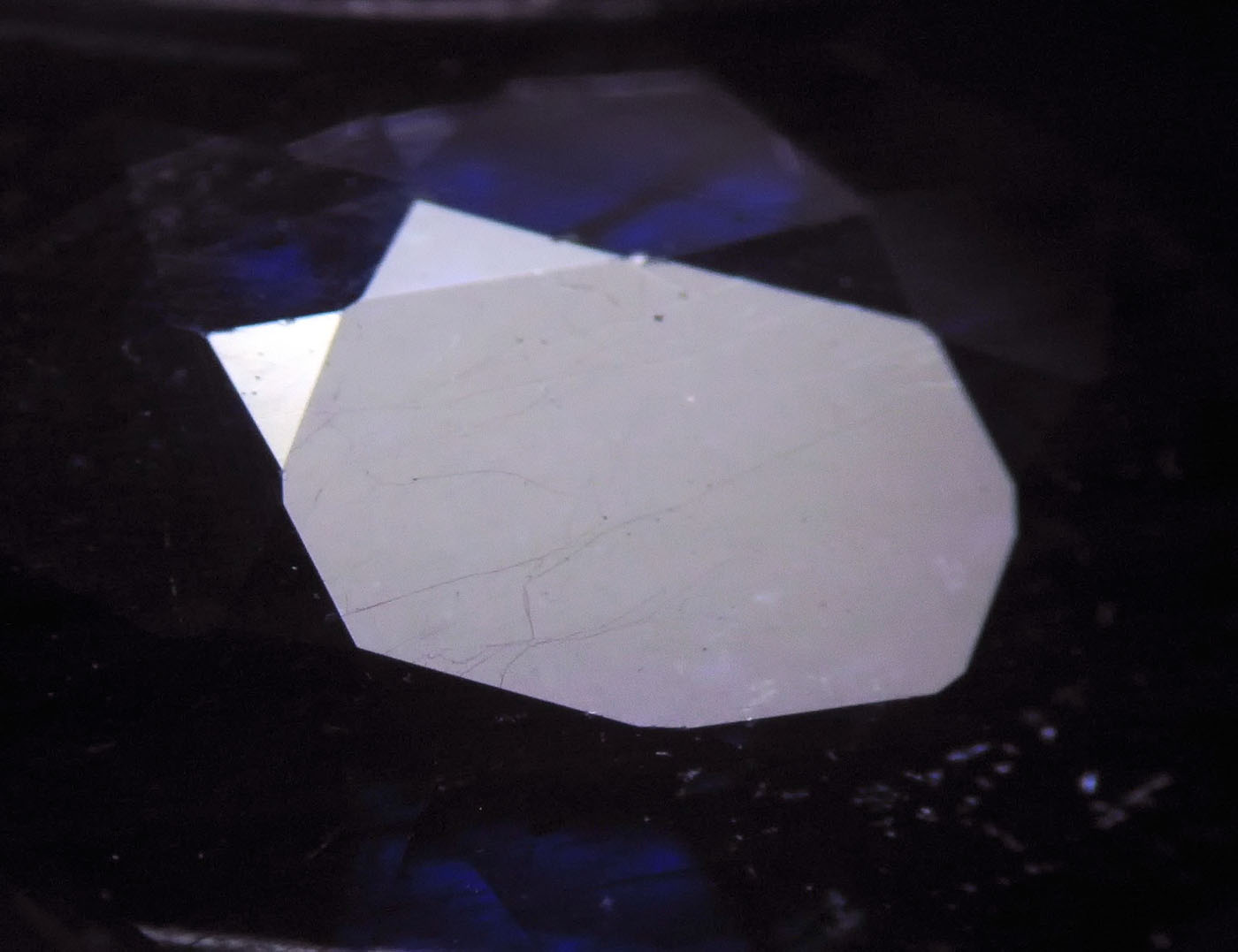

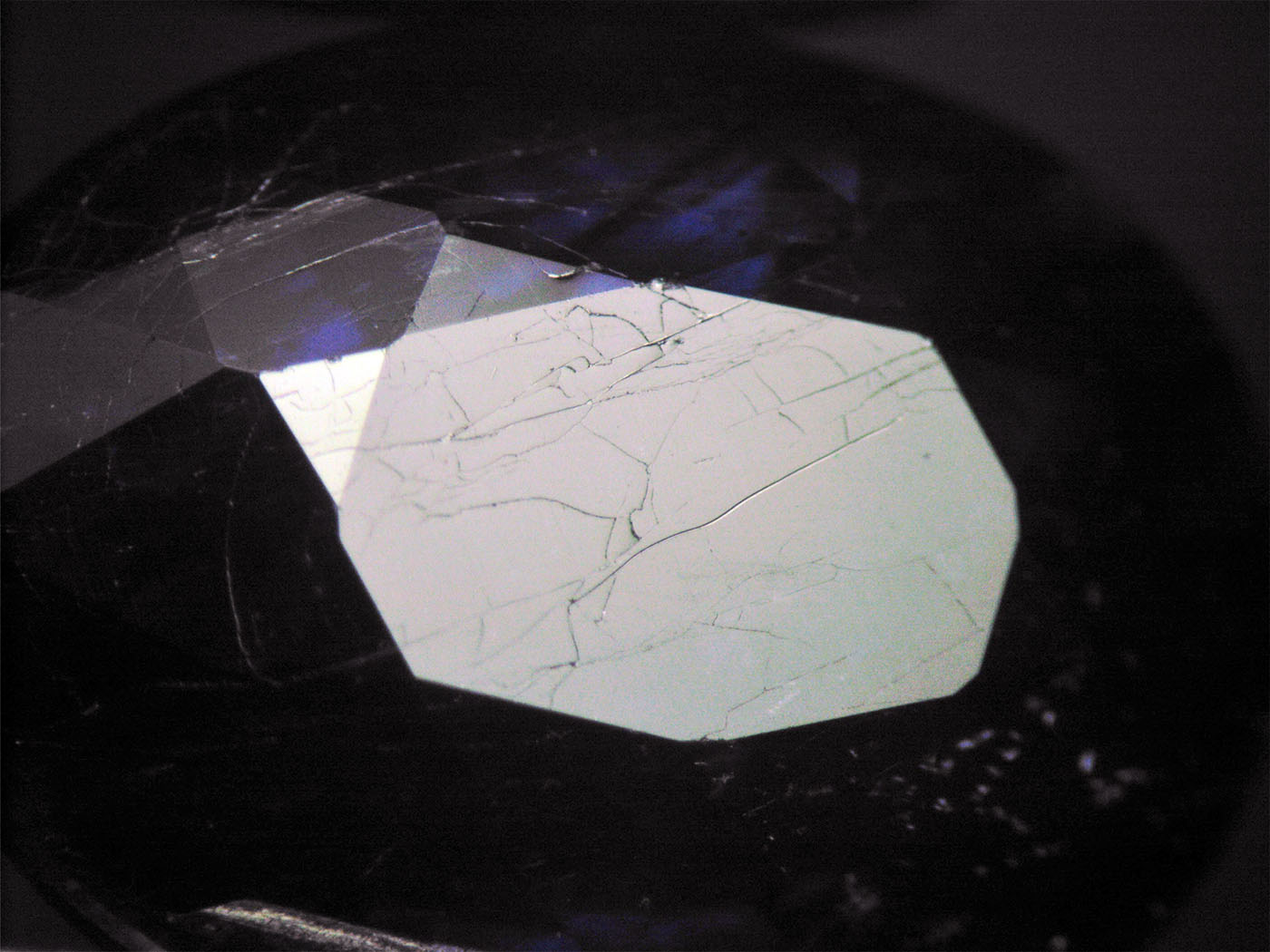

The new generation of stones (Figures 7–12) reveals features that are typical of glass-filled rubies. Fissure fillings show a luster much lower than the surrounding sapphire, and also showed serious undercutting, suggesting it was of far lower hardness. In addition, the fissures contained what appeared to be flattened gas bubbles that stood out in high relief from the surrounding glass filler.

The glass filler itself showed a deep blue color, particularly if the gem was examined in diffused light-field illumination. When using oblique or dark-field illumination, a yellow/blue/pink flash effect from the fissures was seen, similar to what one encounters in glass-filled rubies.

|

|

|

Figure 5. |

|

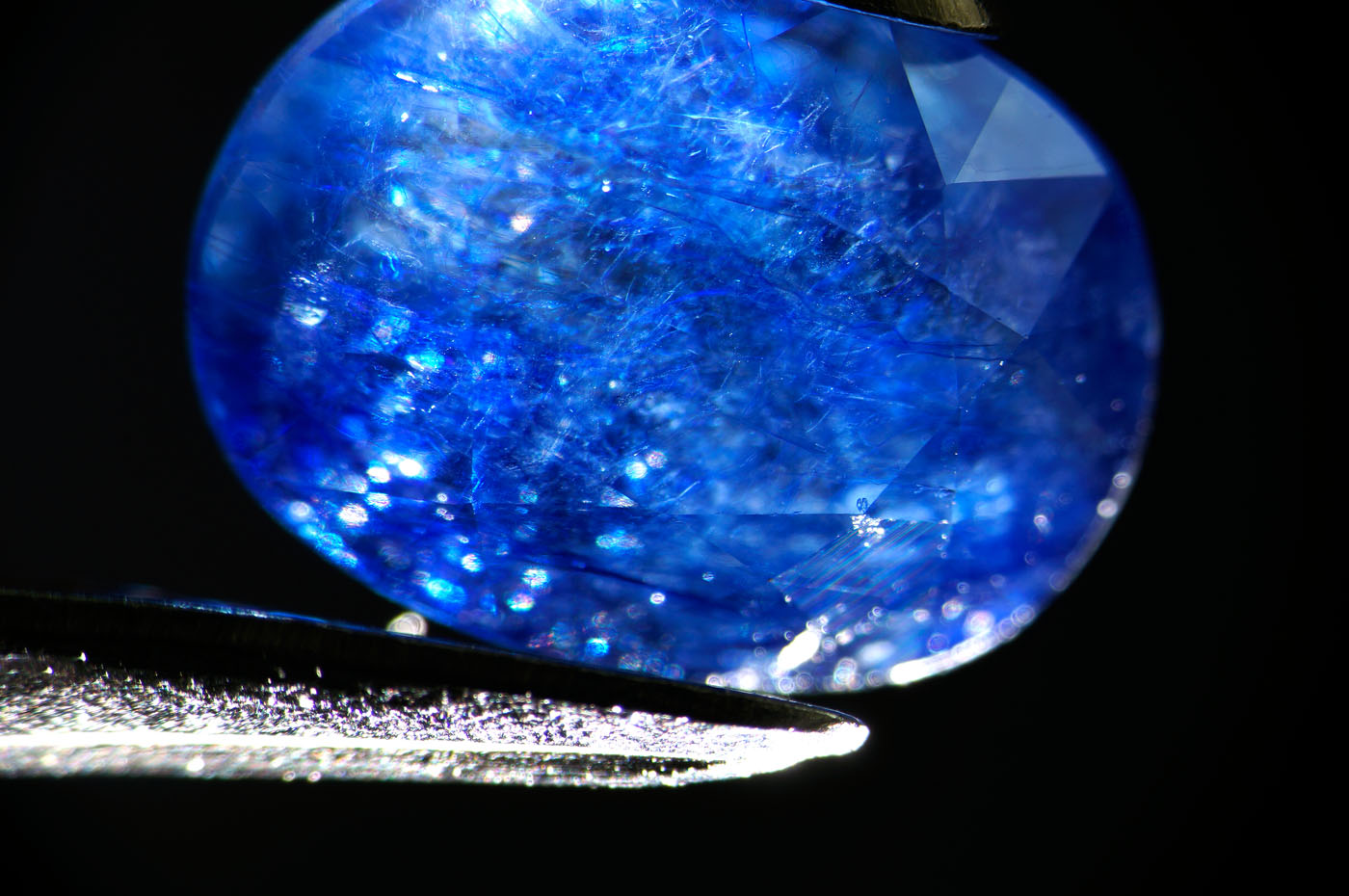

Figure 7. At low magnification the new generation stones display a roiled appearance caused by the network of glass-filled fissures. Dark-field illumination. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Figure 7. At low magnification the new generation stones display a roiled appearance caused by the network of glass-filled fissures. Dark-field illumination. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

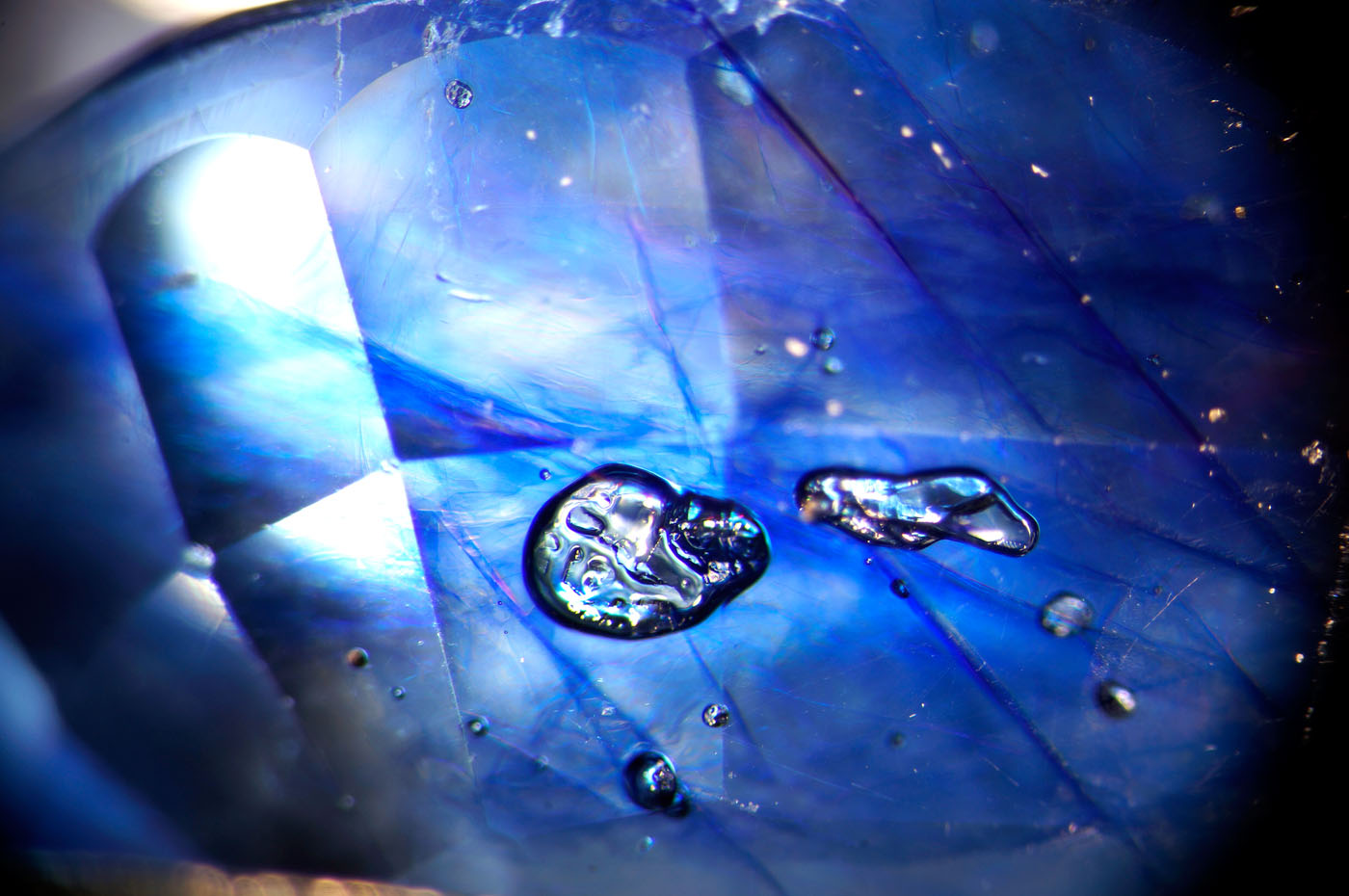

Figure 8. Flattened gas bubbles stand out in high relief in the glass filler of this cobalt-glass filled sapphire. Oblique fiber-optic illumination. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Figure 8. Flattened gas bubbles stand out in high relief in the glass filler of this cobalt-glass filled sapphire. Oblique fiber-optic illumination. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

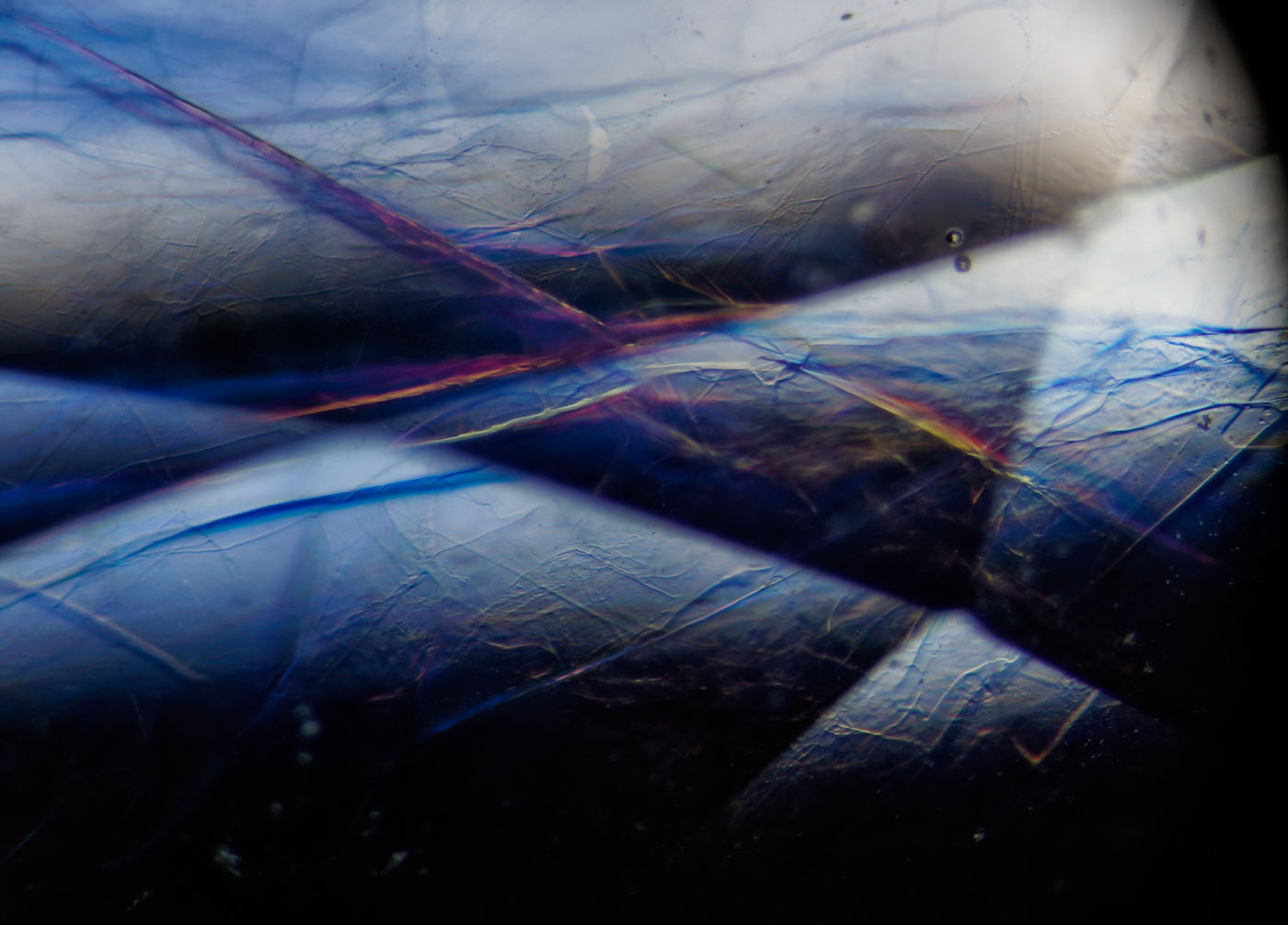

Figure 9. The lead-glass filler often produced a yellow/blue/pink flash effect as the stone was rotated in the microscope. Oblique fiber-optic illumination. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Figure 9. The lead-glass filler often produced a yellow/blue/pink flash effect as the stone was rotated in the microscope. Oblique fiber-optic illumination. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

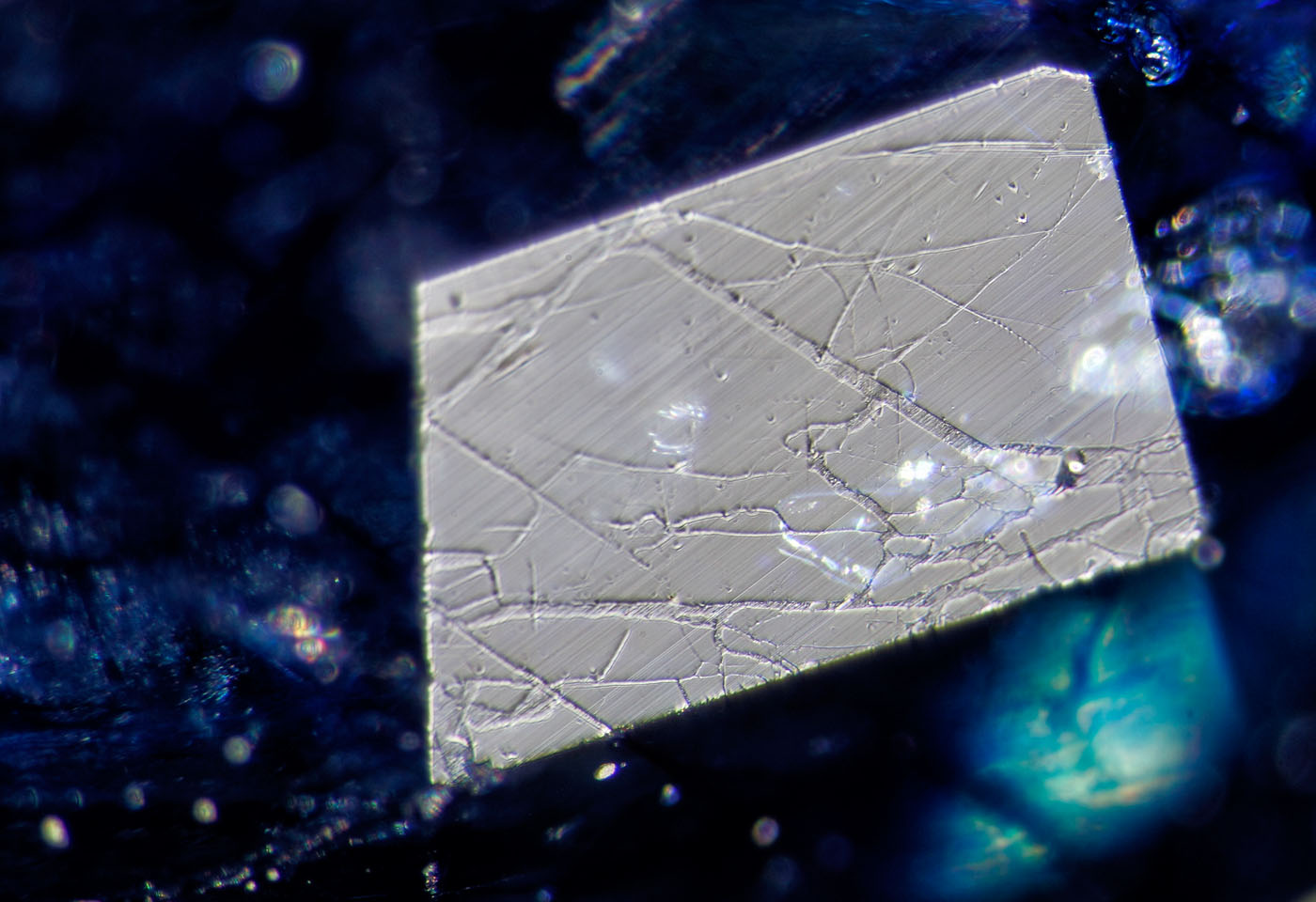

Figure 10. A small facet viewed in reflected light reveals a network of fissures filled with glass. The low hardness of the glass shows serious undercutting compared with the surrounding sapphire. Surface-incident fiber-optic illumination.

Figure 10. A small facet viewed in reflected light reveals a network of fissures filled with glass. The low hardness of the glass shows serious undercutting compared with the surrounding sapphire. Surface-incident fiber-optic illumination.

Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Figure 11. When viewed with transmitted light field illumination, rich blue color concentrations are found in the fissures.

Figure 11. When viewed with transmitted light field illumination, rich blue color concentrations are found in the fissures.

Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

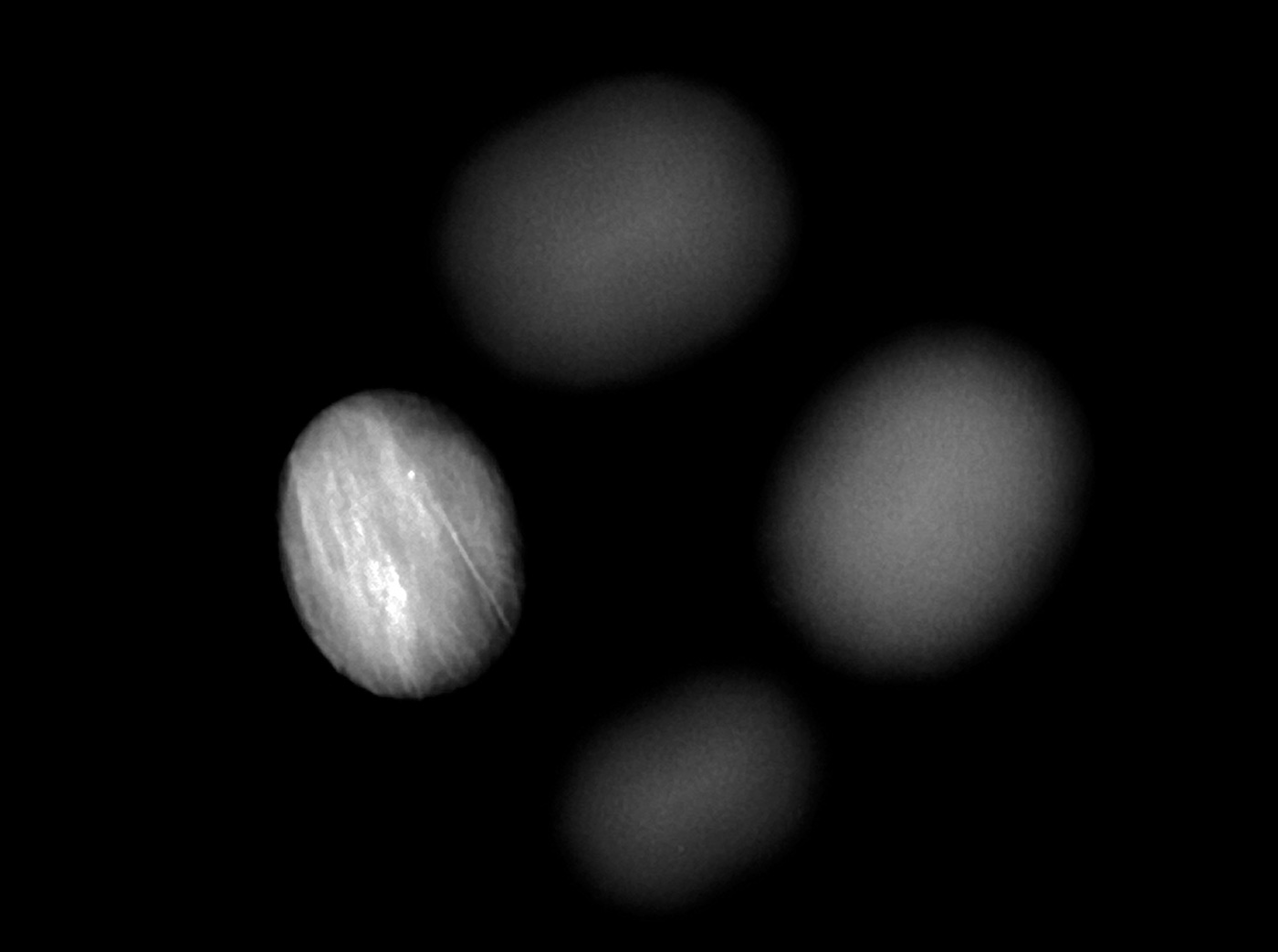

Figure 12. Immersion in di-iodomethane (methylene iodide) in diffuse light-field illumination quickly reveals the blue color concentrations in the cobalt-glass filled sapphires (top two stones), whereas natural sapphires show angular color zoning (lower two stones). Image corrected to remove yellow color of liquid. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Figure 12. Immersion in di-iodomethane (methylene iodide) in diffuse light-field illumination quickly reveals the blue color concentrations in the cobalt-glass filled sapphires (top two stones), whereas natural sapphires show angular color zoning (lower two stones). Image corrected to remove yellow color of liquid. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Advanced testing

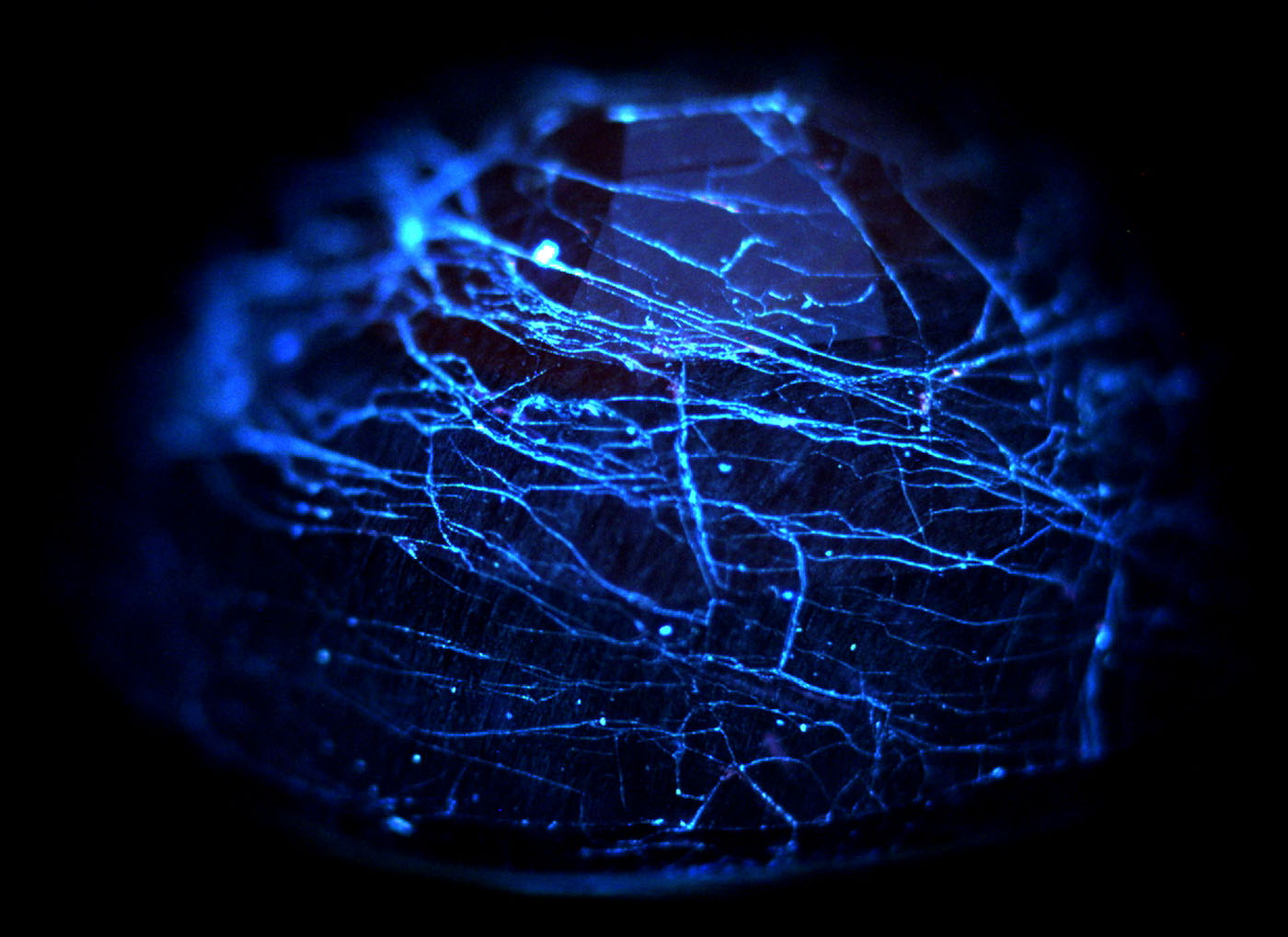

DiamondView™

Two cobalt-doped glass-filled sapphires were examined with the De Beers DiamondView™. This is essentially a powerful short-wave UV light source. Both stones showed a strong chalky blue fluorescence concentrated in a spider-web like pattern of tiny fissures, corresponding to the areas of glass infilling (Figure 13).

Figure 13. DiamondView™ image of a cobalt-doped glass-filled sapphire, showing chalky blue fluorescence from the glass-filled fissures. Image: GIT

Figure 13. DiamondView™ image of a cobalt-doped glass-filled sapphire, showing chalky blue fluorescence from the glass-filled fissures. Image: GIT

Chemistry

In order to determine the identity of the filler, energy dispersive x-ray fluorescence (ED-XRF) analysis was carried out. As expected, cobalt (Co) and lead (Pb) in the blue glass filler were detected. Further analysis by X-radiography also revealed opaque areas in the X-ray images; these coincided with the positions of glass-filled fractures and cavities (Figure 14).

Figure 14. X-ray image of the new generation cobalt-doped glass-filled sapphire (left), showing opaque areas along the fractures. In contrast, a natural sapphire (top), an original Tanusorn-treated sapphire (right) and a Verneuil synthetic sapphire show no such x-ray opacity in the fissures. Image: GIT

Figure 14. X-ray image of the new generation cobalt-doped glass-filled sapphire (left), showing opaque areas along the fractures. In contrast, a natural sapphire (top), an original Tanusorn-treated sapphire (right) and a Verneuil synthetic sapphire show no such x-ray opacity in the fissures. Image: GIT

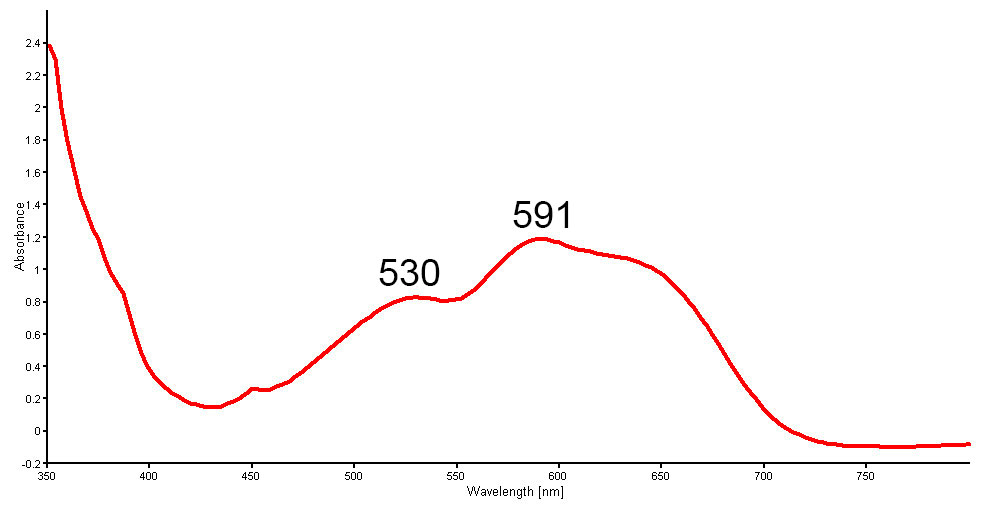

Spectra

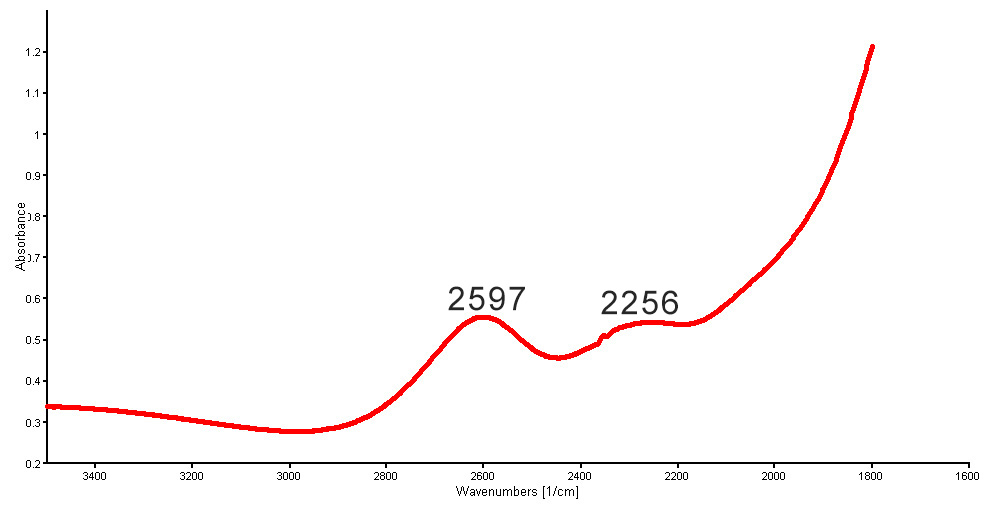

The UV-Vis-NIR spectra shows clear cobalt-related absorption bands peaked at 530, 591 and 625 nm (Figure 15) that perfectly matched our reference spectra for “cobalt-blue glass”. The Mid-IR spectra also show absorption humps at around 3500, 2597 and 2256 cm-1 (Figure 16), which are commonly found in the normal glass-filled ruby.

Figure 15. Non-polarized UV-Vis-NIR spectra of a new generation Tanusorn-treated sapphire showing cobalt-related absorption bands peaked at 530 and 591 nm. An additional peak at 625 nm is sometimes seen. Spectrum: GIT

Figure 15. Non-polarized UV-Vis-NIR spectra of a new generation Tanusorn-treated sapphire showing cobalt-related absorption bands peaked at 530 and 591 nm. An additional peak at 625 nm is sometimes seen. Spectrum: GIT

Figure 16. Mid-IR spectrum of a new generation Tanusorn-treated sapphire showing absorption bands at 2,597 and 2,256 cm-1; these bands are often present in glass-filled stones. Spectrum: GIT

Figure 16. Mid-IR spectrum of a new generation Tanusorn-treated sapphire showing absorption bands at 2,597 and 2,256 cm-1; these bands are often present in glass-filled stones. Spectrum: GIT

Stability Testing

Because glass-filled rubies are known to be extremely unstable (Scarratt, 2012; LMHC, 2012), the authors conducted stability testing on some of the stones. These tests included ultrasonic cleaning, heating with a jeweler’s torch and immersion in strongly basic and strongly acidic solutions. The results are contained in Table 2.

| Tools and Reagents | Time/Temperature | Results | Conclusion | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasonic cleaner for 10 minutes | 10 minutes in water at room temperature | No change | Possibly safe; needs further testing | – |

| Exposure to flame of jeweler’s torch for one minute | 1 minute at approx. 1000 °C | Glass filler showed obvious decay | Avoid heat of any kind | – |

| Immersion in strongly acidic solution (sulfuric acid H2SO4 at 98% concentration) | 30 minutes at room temperature | Glass filler slightly dissolved | Avoid any and all contact with strong acids particularly hydrofluoric acid, which is known to quickly dissolve silica-based glasses | This acid in dilute form (20%) is commonly used to clean jewelry surfaces before plating |

| Immersion in strongly basic solution (sodium hydroxide – NaOH) | 10 minutes/boiling | Glass filler strongly dissolved; open fractures clearly observed | Avoid any and all contact with strong bases | Test performed by treater in Chanthaburi |

Figure 17. Boiling in a strongly basic solution (sodium hydroxide) for ten minutes caused the glass filler to quickly deteriorate. Photo: Thanong Leelawatanasuk

Figure 17. Boiling in a strongly basic solution (sodium hydroxide) for ten minutes caused the glass filler to quickly deteriorate. Photo: Thanong Leelawatanasuk

Figure 18. Table facet of one cobalt-doped glass-filled sapphire before (left) and after (right) heating with a jeweler’s torch. (Photos: Thanong Leelawatanasuk).

Figure 18. Table facet of one cobalt-doped glass-filled sapphire before (left) and after (right) heating with a jeweler’s torch. (Photos: Thanong Leelawatanasuk).

Conclusions

Glass-filled (a.k.a. ‘composite) rubies have become ubiquitous since their appearance in late 2004 (Pardieu, 2005; GIT, 2008). It is very possible that this scenario will be repeated with cobalt-doped glass-filled sapphires, since the treatment allows a near-colorless sapphire of poor clarity to mimic the appearance of a blue sapphire of higher value. Thus it is important for traders, jewelers and gemologists to be familiar with the material and the methods of identification.

A simple Chelsea filter screening test can easily separate the latest generation of stones seen thus far from both natural, heated (including titanium diffused) and synthetic sapphires. This preliminary identification can be confirmed by the lack of pleochroism and particularly the distinctive internal and surface features visible under magnification. Advanced testing can also be used, but is not necessary in most cases.

About the Authors

Leelawatanasuk, T.,

Atichat, W.,

Pisutha-Arnond, V.,

Wattanakul, P.,

Ounorn, P.,

Manorotkul, W.

Hughes, R.W.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mr. Tanusorn Lethaisong and Ms. Sasitorn Boongkawong for supplying the samples used in this study and information on the treatment. In a world where treaters are often reluctant to share information with gemologists, we were extremely pleased by this cooperation.

Notes

First published in the Australian Gemmologist (2013, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp. 14–20). The visible spectrum peak that was labelled as 544 nm in the original version of this article has been corrected to 530 nm.

References & Further Reading

- Abduriyim, A. (2007) Treatment in blue sapphire "Super Diffusion Tanusorn"–filling treatment with cobalt-coloured lead glass. GAAJ-Zenhokyo Online Report; accessed 26 March, 2013.

- GIT (2007) New blue treated sapphire. Gem & Jewelry Institute of Thailand Online Report; accessed 26 March, 2013.

- GIT (2008) Update on an uncommon lead-glass treated ruby. Gem & Jewelry Institute of Thailand Online Report; accessed 26 March, 2013, Bangkok.

- Leelawatanasuk, T. (2012) Urgent lab info: “Blue dyed and clarity modified sapphire with cobalt + lead-glass filler in fractures and cavities”. Gem & Jewelry Institute of Thailand Online Report; accessed 14 March, 2013, 4 pp.

- LMHC (2012) Corundum: with glass filled fissures, with glass filled cavities, with/and glass (manufactured product). Laboratory Manual Harmonization Committee Information Sheet, No. 3, Version 9, last updated December 2012; accessed 27 March, 2013, 3 pp.

- Pardieu, V. (2005) Lead glass filled/repaired rubies. Asian Institute of Gemological Sciences Gem Testing Laboratory Online Report; accessed 14 March, 2013, 16 pp.

- Scarratt, K. (2012) A discussion on ruby-glass composites & their potential impact on the nomenclature in use for fracture-filled or clarity enhanced stones in general. Gemological Institute of America Online Report; accessed 26 March 2013, 23 pp.

- Smith, C.P. (2013) Cobalt-colored composite sapphires now entering the market. American Gemological Laboratories Press Release; accessed 27 March, 2013, 5 pp.