A discussion of the definition of padparadscha sapphire, from early to modern times, along with the difficulty in standardizing such definitions.

Om mani padme hum – Hail the jewel in the heart of the lotus Buddhist mantra

Padparadscha Sapphire & the Ownership of Words

Padparadscha sapphire is a special variety of gem corundum, featuring an often delicate color that is a mixture of red and yellow – a marriage between ruby and yellow sapphire. The question of just what qualifies for the princely kiss of “padparadscha” is a matter of hot debate, even among experts.

The original locality for padparadscha was Sri Lanka (Ceylon) and many purists today believe the term should be restricted only to stones from Ceylon. However, fine stones have also been found in Vietnam’s Quy Chau district, Tanzania’s Tunduru district, and Madagascar. Stones from each of these areas are often heat-treated and this is done at fairly low temperatures (1200°C and below) and such heat treatment is not always detectable.

Padparadscha sapphires are considered among the most beautiful and valuable of the corundum gems. Prices for padparadschas vary greatly according to size and quality. At the top end, they may reach as much as US$50,000 per carat or more.

For many years now, padparadscha has been narrowly defined by Western gemologists as a Sri Lankan sapphire of delicate pinkish orange color. The term padparadscha is actually a corruption of the Sanskrit/Singhalese padmaraga (padma = lotus; raga = color), a color akin to the lotus flower (Nelumbo Nucifera ‘Speciosa’).

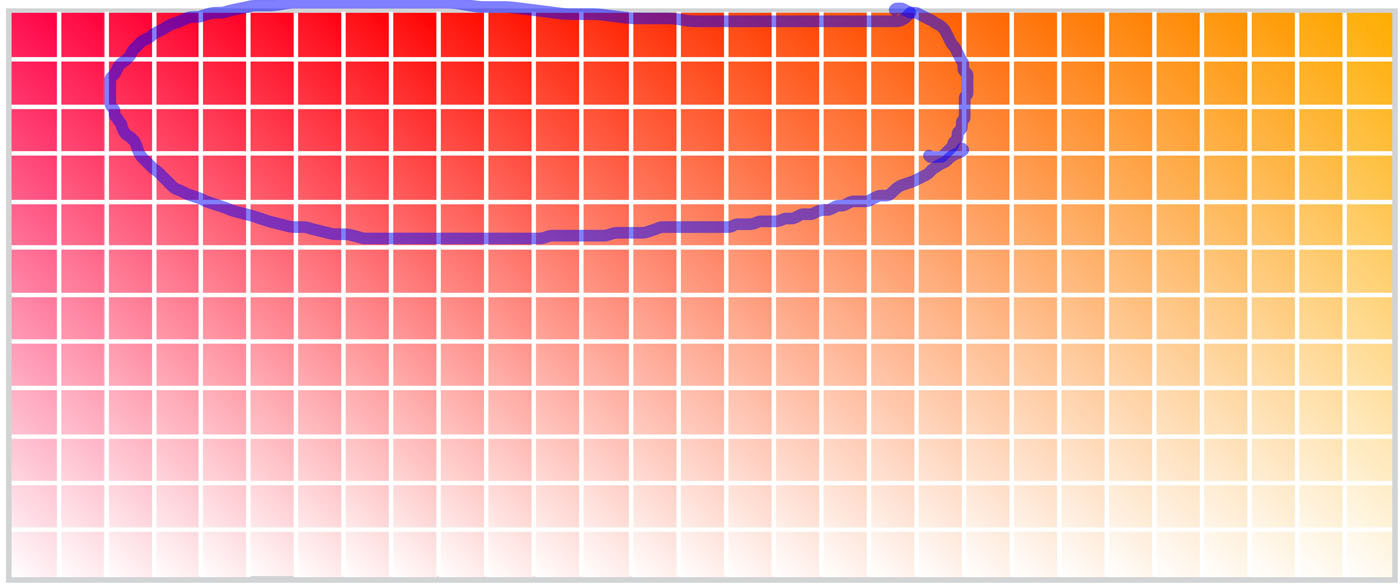

Figure 1. A marriage made in heaven

Figure 1. A marriage made in heaven

The ideal color of a padparadscha has been described by some as the marriage between a lotus flower and a sunset, each shown above in Sri Lanka. Photos © Wimon Manorotkul (left) & Richard W. Hughes (right).

Wojtilla provides the following from a Sanskrit source under his description of ruby:

Arthasastra [an ancient Sanskrit book] knows the following names: saugandhika (lotus-coloured), padmaraga (the same)…

– G.Y. Wojtilla, 1973

Ever look at a lotus? I’ve stuffed my snout into blossoms all the way from Beruwala to Badulla and have come up with only one conclusion – they are far more red than orange. Indeed, in ancient times padma raga was a sub-variety of ruby, as indicated by the Garuda Purana:

10. Some of the rubies have the colour of vermillion, red lotus and Saffron; some have the colour of Laksa juice; although the red colour is uniform throughout; their centre has a special manifest brilliance; the rubies are self-luminous.

32. He who is mentally and bodily pure and wears Padmaraga whose crimson colour is heightened by its good qualities is never sullied by any sort of evil.

– J.L. Shastri (ed.), The Garuda Purana (400–1000 AD)

While virtually every writer on the subject makes the lotus comparison, certain others also add the concept of fire or sunset, almost an aurora (sunrise) red-orange. Here is an early definition from the Indian subcontinent, dating from about 1200–1300 AD:

Varieties of Ruby

That which spreads its rays like the sun, is glossy, soft to the touch (komala?), resembling the fire, like molten gold and not worn off is paümaraya [padmaraga].

– Sarma, 1984, Thakkura Pheru’s Rayanaparikkha – A Medieval Prakit text on Gemmology

Molten gold? That sounds nothing like a lotus color.

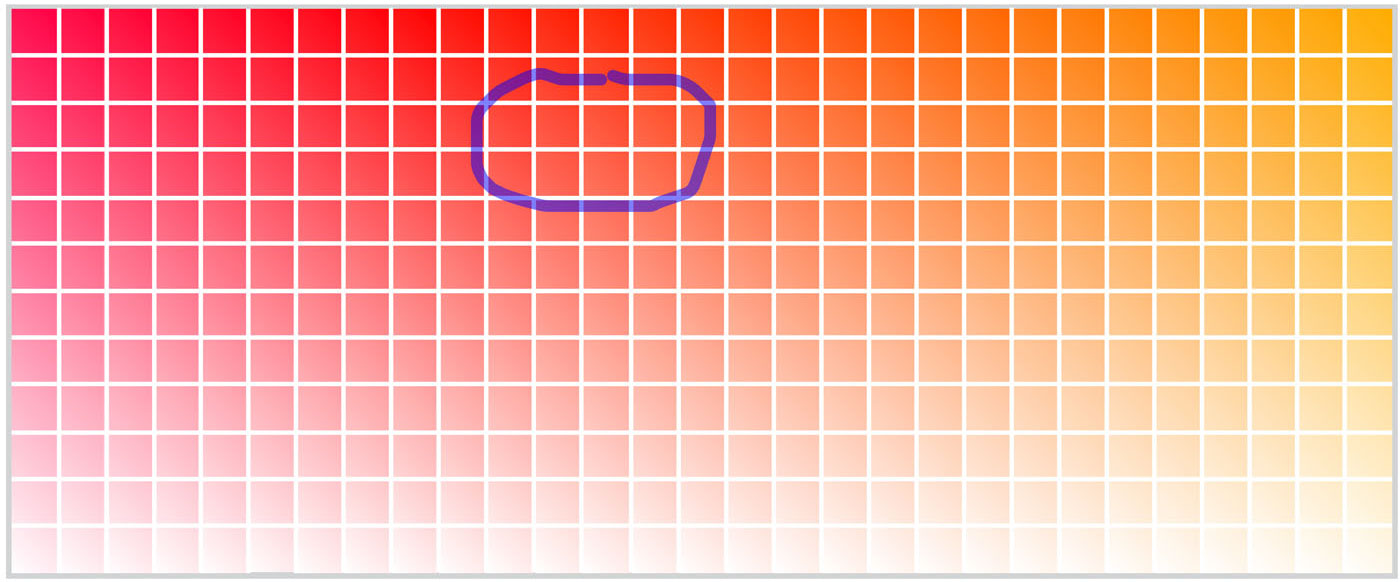

Figure 2. Vermilion and saffron

Figure 2. Vermilion and saffron

Some early definitions of padmaraga include references to vermilion (above; Pushkar, India) and saffron (inset; ‘Ispanya Saffron’). Photos: Wikipedia.

A number of important Arab accounts of gems from the Indian subcontinent exist, but perhaps none are better than that of al-Beruni, who had this to say in regard to ruby:

Al-Kindi has described the wardi (rose-colored) variety first. It is rose-colored with a little whiteness, but he has accorded preference to the khayri (Hollyhock-hued), kind over the wardi. Above this is the ahmar ‘usfuri (red-saffron-coloured) kind which has the colour of bright saffron with a tinge of yellow. Then there is the bahramani ‘usfuri kind which is pure, and is devoid of any starchy colour. The yellow kind becomes progressively precious as the red colour becomes dominant until it reaches full redness.

– al-Beruni, ca. 11th century (Beruni, 1989)

The range of padparadscha here definitely includes everything from yellow-orange through red-orange into red.

Moving on to Sri Lanka itself, we have a more modern account from 1855:

The Topaz (puspa raga, Singhalese) claims notice next. There are two varieties of it: the “ratu puspa raga” and “kaha puspa raga.” The former is of a bright yellow color, with a reddish tinge and is the more valued. The latter is pure bright yellow. The first variety is scarce, and the second is comparatively plentiful. The topaz and the sapphire seem to be species of the same stone differing only in color – it is not unfrequent to find a piece of stone partly yellow and partly blue. This stone is not much sought after by Europeans, but it is prized among the Singhalese. It is said to sell well at the Presidencies of India and in Arabia.

– J.F. Stewart, Gems and Gem Searching in Saffragam

Ceylon Observer, June 11, 1855, (from Ferguson, 1888)

And a more recent reference from Sri Lanka:

A sapphire of orange-red or pink colour, is locally referred to as padmaraga (padma – lotus flower; raga – colour). Many scholars call this variety padmarascha, which is a misnomer. The term raga means colour, attraction, desire, musical rhythm and pollen; therefore, the name for the lotus-flower coloured corundum should be padmaraga, and not padmarascha. However, lotus flowers are also found in white, but in this instance the colour referred to is the orange-red or pink lotus flower, growing in Shri Lanka.

There is also the yellow sapphire of Shri Lanka, commonly called pushparaga in Singhalese. The term pushpa means flower; as raga is colour and also means pollen, hence pushparaga is the “colour of pollen.” Although pollen can be brownish yellow or yellow in colour, the Shri Lankan gem trade from ancient times to the present, has always referred to pushparaga as a yellow variety of corundum.

The important words to consider in the latter example are flower, colour and pollen, in the origin of the name, pushparaga. However, in both examples of padmaraga and pushparaga, the term raga refers to the colour. Therefore, the word padmaraga also confirms that the correct term for the orange-red or pink sapphire should be accepted as padmaraga and not padmarascha.

– D.H. Ariyaratna, 1993

Yet still another modern Sri Lankan reference:

The term pathmaraga is applicable to a corundum of an exceptionally pleasing colour which is a result of a combination of colours producing a colour similar to a beautiful sunset red (p. 86) …. The term pathmaraga is a Singhalese term applied to a very special colour variety of corundum, so named after the lotus flower as its colour is sometimes akin to a variety of this flower…. The colour combination produces the rare and beautiful colour of a sunset red at its best as seen across a tropical sky.… The colour of pathmaraga is apparently a combination of yellow, pink and red, with mildly conspicuous flashes of orange (p. 94)….

– Gunaratne and Dissanayake, 1995

There is a reasonable continuity in the Eastern literature. Padmaraga is a blend between yellow sapphire and ruby. No where is the term defined simply in terms of pastel colors.

Figure 3.

Figure 3.

This 1126-ct. crystal was cited by Robert Crowningshield as representing the ideal color of padparadscha. Photo © Tino Hammid

Connecting the plots

So how did we get from padmaraga (a blend of yellow sapphire and ruby) to padparadscha (narrowly defined as a pastel pink-orange sapphire)?

The tightening of the padparadscha definition can be largely traced to a 1983 article by the GIA’s Robert Crowningshield. In it, Crowningshield provided an excellent summary of the origin of the term and what many considered to be ideal examples. Unfortunately, however, the GIA Library at the time did not include many Indian or Arab lapidaries.

Thus Crowningshield was forced to rely on Occidental descriptions. Of those he did quote, at least two (Keferstein, Holland) were not even listed in the references at the end of the article, bringing into question whether Crowningshield actually saw them or simply quoted via third parties. Whatever occurred, the final definition he produced was in the opinion of this author truncated, completely missing the early references to the color being a blend of a lotus flower and sunset as well as the many references to rich colors in the definition that he himself cited.

Crowningshield concluded with these words:

It is clear that the term padparadscha was applied initially to fancy sapphires of a range of colors in stones found in what is now Sri Lanka. If the term is to have merit today, it will have to be limited to those colors historically attributed to padparadscha and found as typical colors in Sri Lanka. It is the GIA’s opinion that this color range should be limited to light to medium tones of pinkish orange to orange-pink hues. Lacking delicacy, the dark brownish orange or even medium brownish orange tones of corundum from East Africa would not qualify under this definition. Deep orangy red sapphires, likewise, would not qualify as fitting the term padparadscha.

– Robert Crowningshield, 1983

In the article, a pink-orange crystal and cut stone (Figures 3 and 12) were held out as prime examples of padparadscha. And they certainly were lovely specimens. But it was a mistake to suggest that they encompassed the full range of possibilities. Excluding “deep orangy red sapphires” is in no way supported by either the historic or contemporary sources in Sri Lanka.

During my many trips to the Island of Gems, I’ve witnessed virtually any ruby/sapphire containing a mixture of red/pink and yellow described as padparadscha, regardless of tone or saturation. Clearly, locals do not limit their palette to only the pastel colors and, from the historic definitions I’ve quoted, nor did the ancients.

Enter the LMHC

On June 16–18 2005, members of the Laboratory Manual Harmonisation Committee (LMHC) met in Milan, Italy to consider a standardized definition of padparadscha. According to their website...

The goal of the Laboratory Manual Harmonisation Committee is to achieve the harmonisation of gemmological report language and thereafter the revision of this harmonised report language as used by LMHC members. The LMHC meets several times a year to update or add to the contents of a manual. When they are relevant to the trade, parts of this manual are released in the form of Information Sheets. The opinions or findings in these documents are based on the state of knowledge at the time of the latest publication and may change as new information becomes available.

The LMHC is a group of the world’s major laboratories For more than a decade, representatives of these laboratories have met to discuss the harmonization of identification procedures and wording on gemstone reports.

The core of the LMHC padparadscha definition at the time of writing (2013) is as follows:

Padparadscha sapphire is a variety of corundum from any geographical origin whose colour is a subtle mixture of pinkish orange to orangey pink with pastel tones and low to medium saturations when viewed in standard daylight.

The name 'padparadscha sapphire' shall not be applied in the following cases:

– If the stone has any colour modifier other than pink or orange.

– If the stone has major uneven colour distribution when viewed with the unaided eye and the table up +/- 30°.

– The presence of yellow or orange epigenetic material in fissure(s) affecting the overall colour of the stone.

– If the stone has been treated as described in Information Sheets #2 and #3.

– If the stone has been treated by irradiation.

– If the stone has been dyed, coated, painted, varnished or sputtered.

I believe most of these criteria are reasonable. You want the color to be from the stone itself, not a stain in a fissure; similarly, you don't want the stone to be irradiated, dyed or coated.

However where I differ is in the realm of tone and saturation. I do believe that padparadschas can and do have saturations that go well beyond "low to medium." Indeed, the finest (and most expensive) padparadschas I have seen are richly saturated. If they were diamonds, they would certainly be described as vivid.

The Christie’s padparadscha

Let’s take this definition and apply it to a major padparadscha. At Christie’s June 7 2005 New York sale, a magnificent 20.84-carat padparadscha sapphire fetched a pretty price, a stunning $374,400 ($18,000 per carat). Mounted in a ring by Henry Dunay (Figure 4), this sale is evidence of the increasing demand for high-quality untreated gemstones. Unfortunately, it is also evidence of the difficulties in defining padparadscha. It featured a 2005 report from one of the LMHC labs.

Figure 4. Simply magnificent

Figure 4. Simply magnificent

In 2005, this 20.84-carat padparadscha sapphire fetched US$18,000 per carat at auction. Photo © 2005 Christie’s Images Ltd.

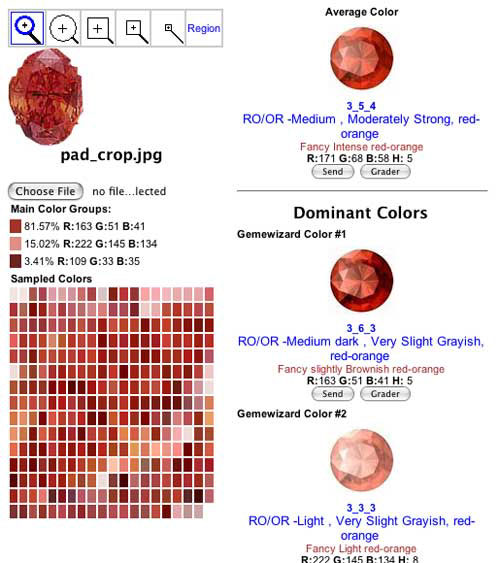

Using the image of this gem from Christie's, I analyzed the color ranges using the GemEwizard, a most interesting tool developed by Menahem Sevdermish. This tool will take any image and break it up into its component colors. In order to do this test on the above image, it was first necessary to digitally remove the mounting, which I did in Photoshop. The results are found in Figure 5 below.

Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The 20.84-ct padparadscha sold in 2005 at Christie’s, also analyzed by the GemEwizard. If the photo is an accurate representation, it is clear the gem would fall outside of the proposed LMHC color range for padparadscha (the irregular shape of the gem is because the mounting was removed in Photoshop)

One can clearly see from the images that, if the picture of the 20.84-ct. pad is representative of the appearance of the actual stone, many of its colors fall outside the range defined by the LMHC, being darker in tone and too rich in saturation. Even if the photo is not representative, I have seen gems with the color as shown. If these do not qualify under the LMHC system, my opinion is that the LMHC should revisit their definition with a view towards making it more broad on the high saturation end.

Padparadscha survey

In order to better answer the question of what dealers today think of padparadscha, the author conducted a brief survey in August–September 2012, both in Sri Lanka and Hong Kong. Nine experienced colored stone dealers took part.

Participants were asked a series of questions concerning the definition of padparadscha, starting with a single sentence that would sum up their definition of padparadscha. The responses were as follows:

- A sapphire with two colored hues, pink & orange.

- Color of the sunset is the perfect color of the padparadscha. A mix of pink & orange.

- A mix of pure orange and pink hues, creating a vivid and pure uniform color.

- A deep pink sapphire with generous orange hue.

- A true balance of pink & orange or orange & pink.

- A balance of pink and orange creating a color similar to a sunset looking west combined with the last hints of orange from the setting sun just after it settles below the horizon.

- Pinkish orange 50-50. Americans prefer a sunset color; lotus color for Japanese.

- A sapphire that is mixture of orange and pink. I prefer one that is 55% orange and 45% pink.

- Orangish pink.

From these responses it is clear that padparadscha is considered by these dealers to be a mixture of pink and orange. Notably absent was any mention of “pastel” in their definitions. Indeed the terms “deep” and “vivid” were mentioned by two of those surveyed.

Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Padparadscha survey Sri Lankan gem expert, Gamini Zoysa (left) taking the padparadscha survey as the author looks on. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul.

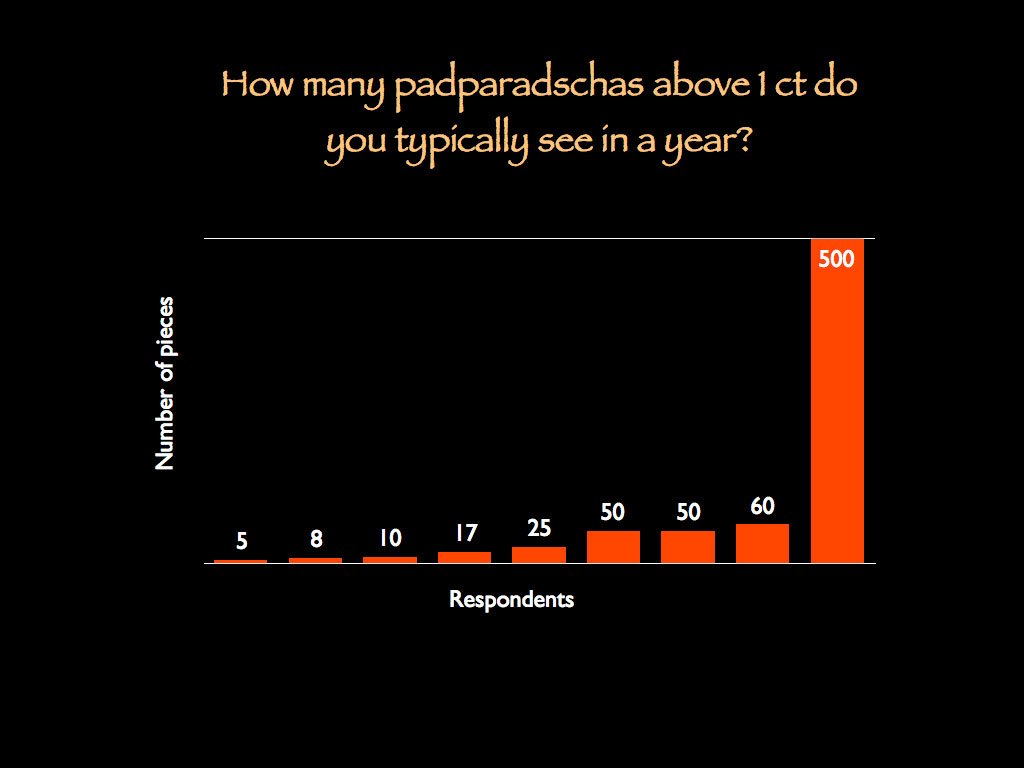

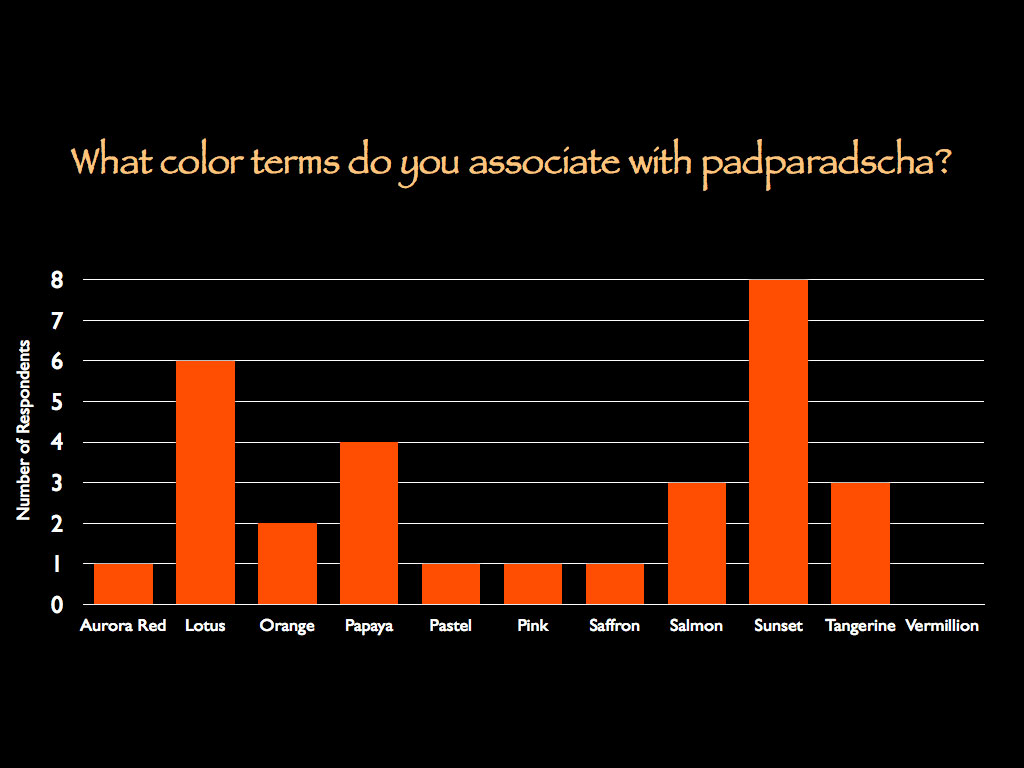

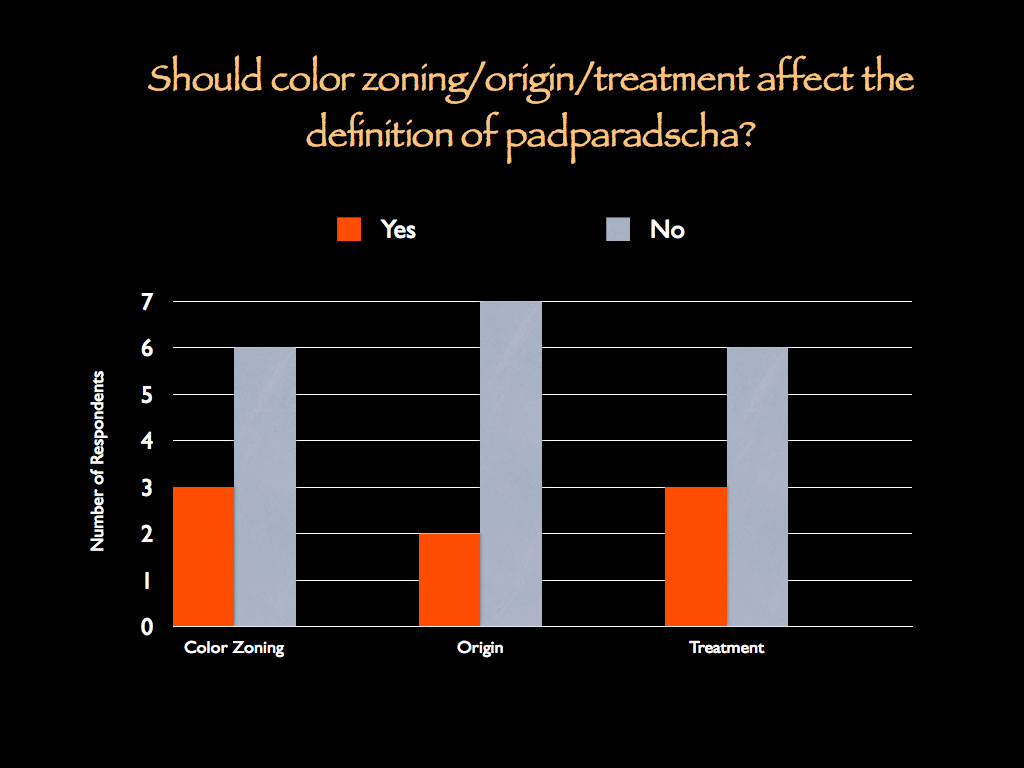

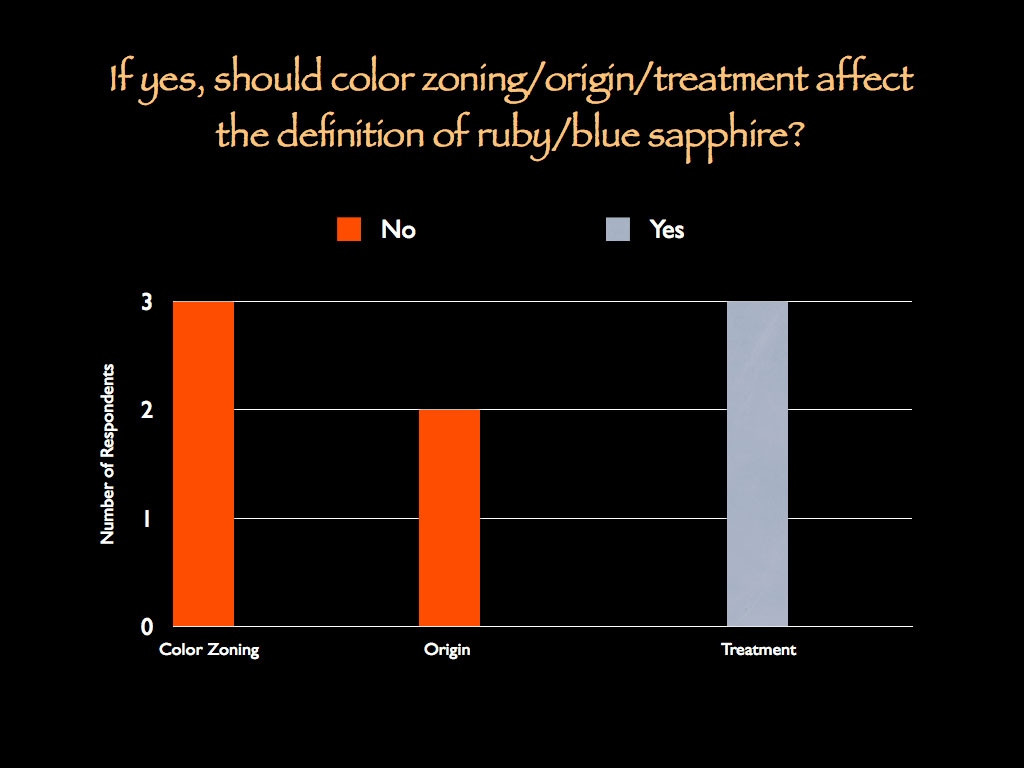

Following this, respondents were questioned regarding the numbers of pads they typically see in a year, the color terms they associate with padparadscha, whether or not color zoning, origin or treatment should affect the padparadscha definition, and if yes, whether those features should also affect the definitions of ruby and blue sapphire. The results from those questions are found in Figures 7–10.

Figure 7. Number of padparadscha

Figure 7. Number of padparadscha

sapphires seen in a year In your work, how many padparadscha sapphires above 1.00 carat do you typically encounter in a year?

Figure 8. Colors of padparadscha

Figure 8. Colors of padparadscha

Which of the following terms do you believe describe the color of a padparadscha sapphire (check all that apply)?

Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Should color zoning, origin or treatment affect the definition of padparadscha?

Figure 10.

Figure 10.

If yes, should color zoning, origin or treatment affect the definition of ruby or blue sapphire?

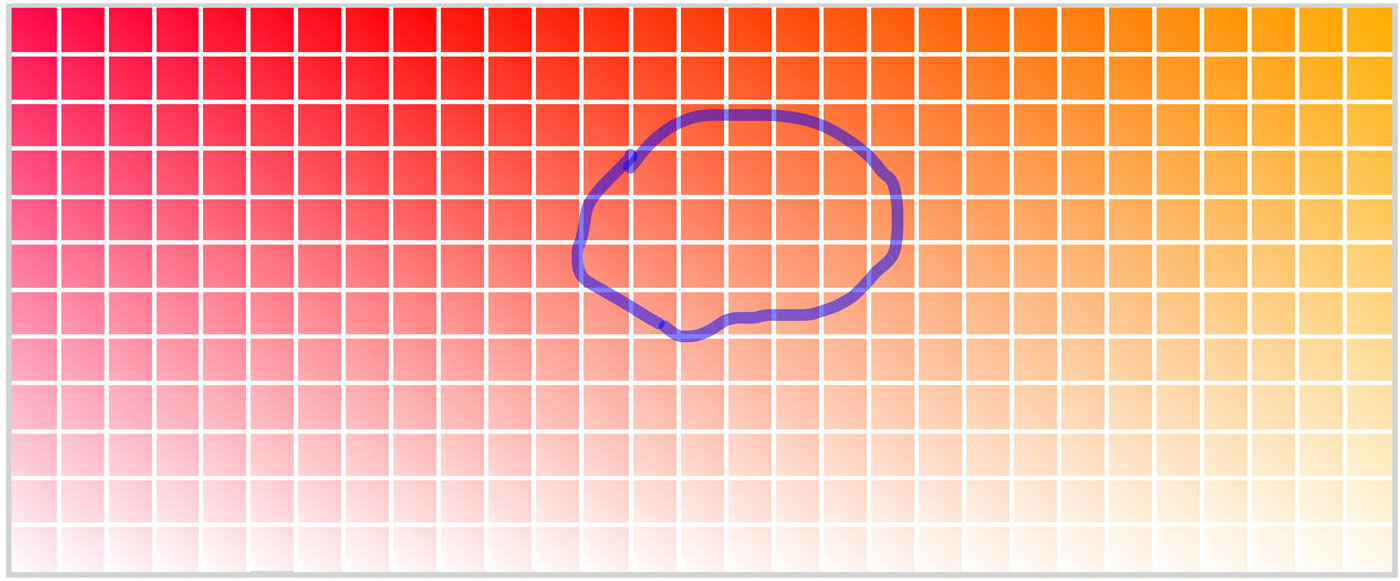

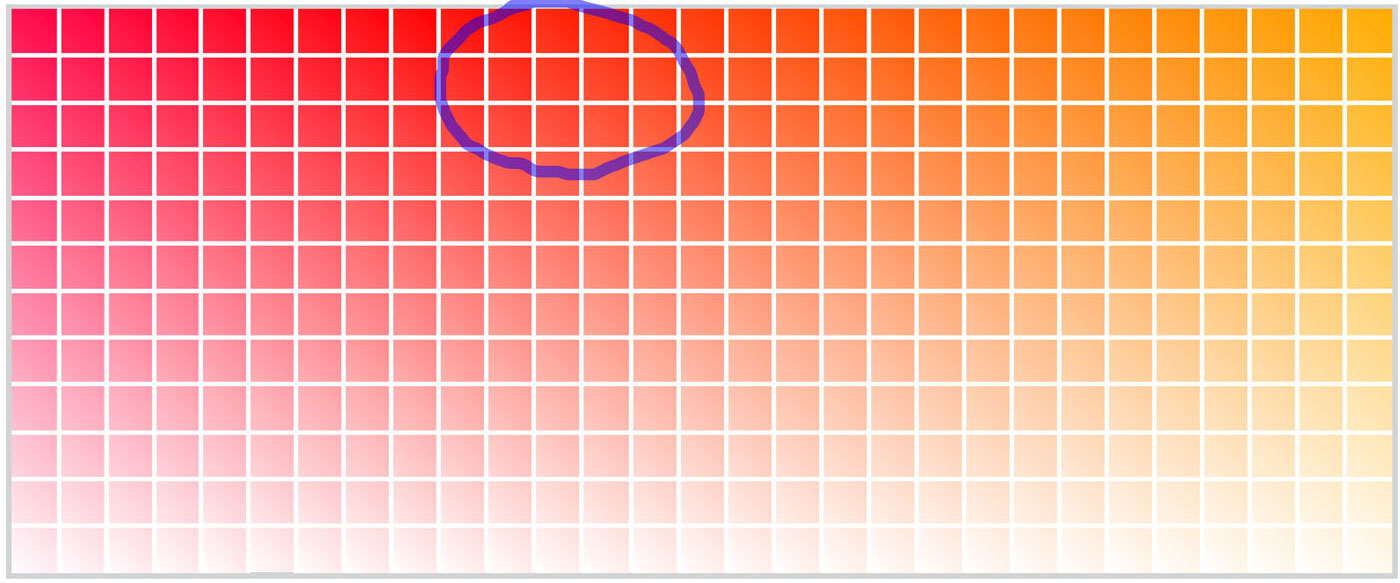

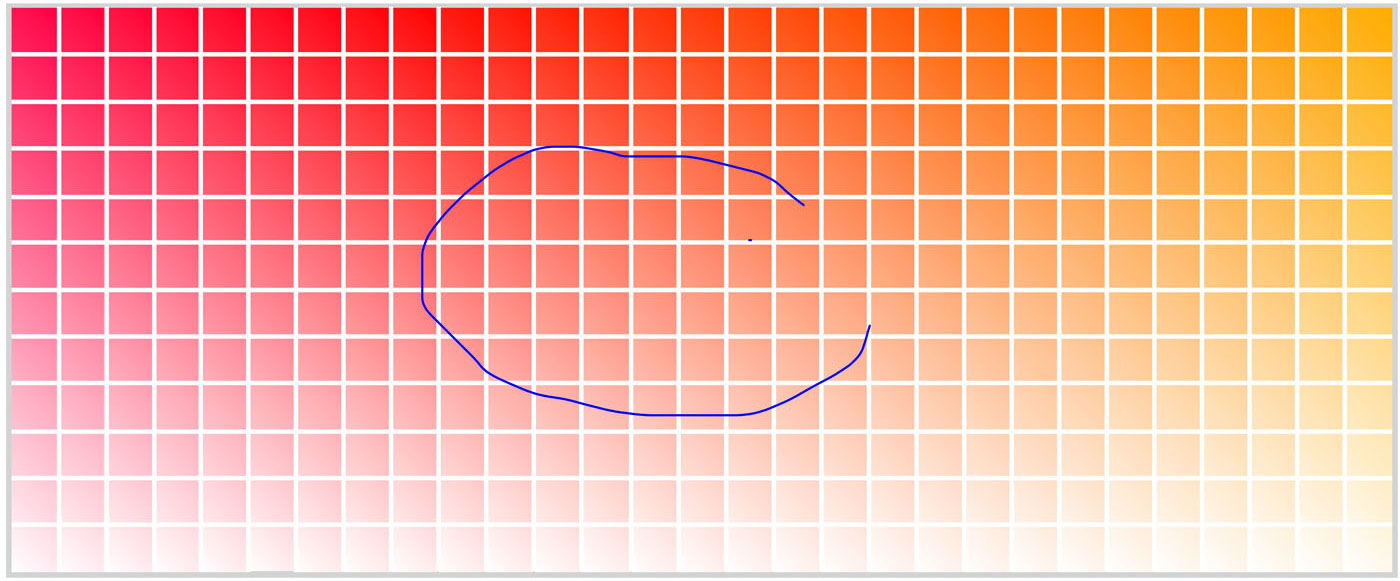

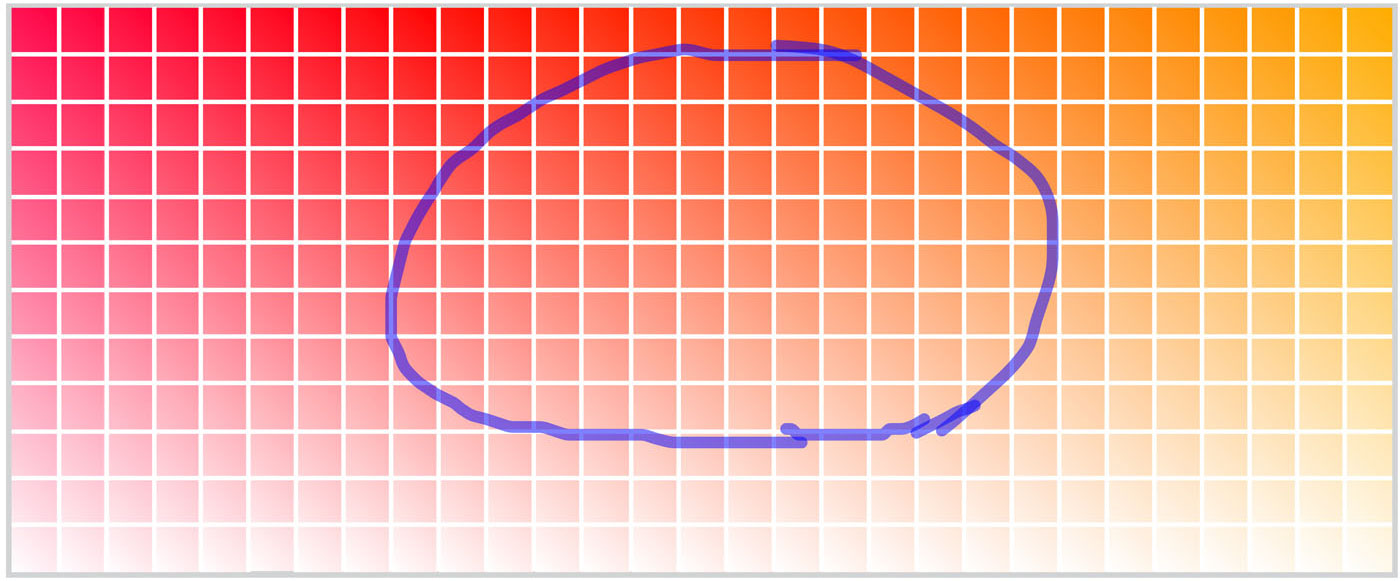

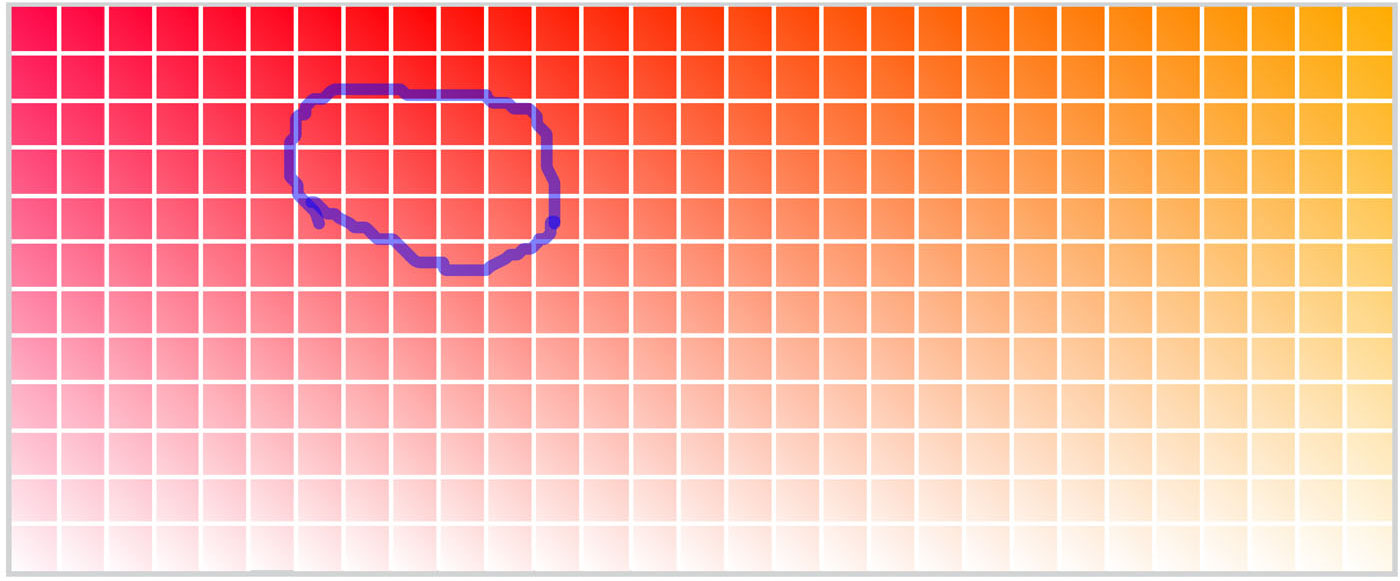

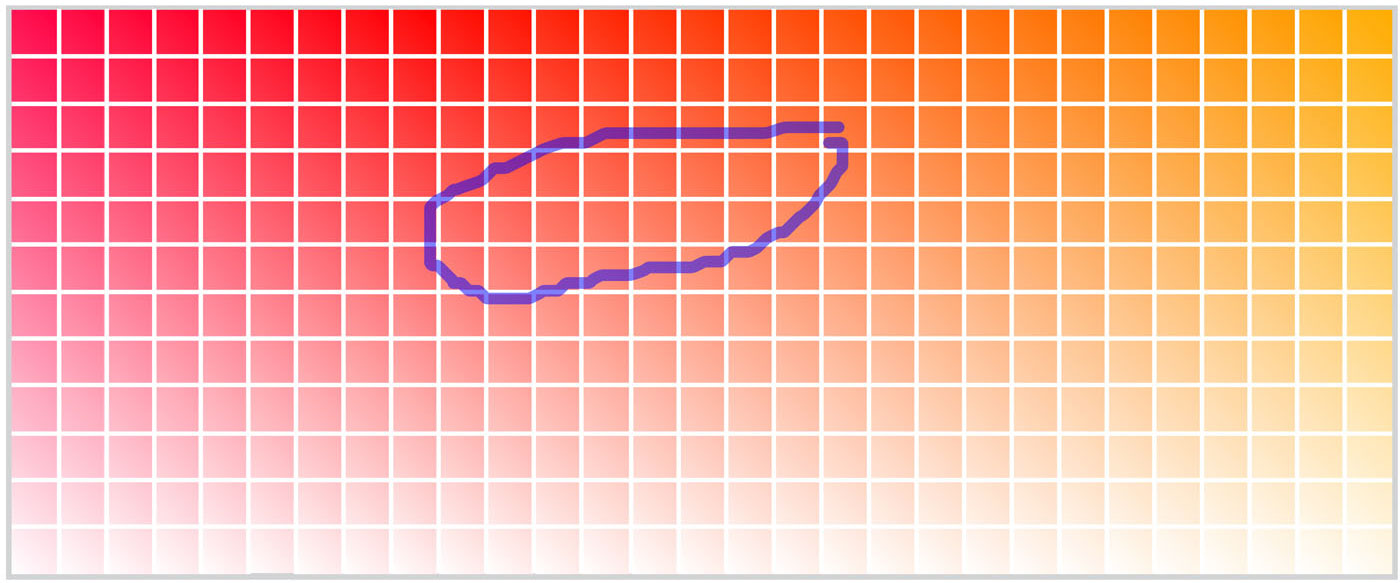

The final feature of the survey was a series of color chips ranging in the horizontal axis from reddish through orange to yellowish, with the vertical axis encompassing increasing tones/saturations. This was similar to the LMHC color chart, but encompassing a wider range of hues and saturations. Participants were asked to draw a line around the region on the chart that they felt best represented the hue and tone/saturation range of padparadscha sapphire. The results are shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11. Padparadscha color range survey results

As part of the padparadscha survey, participants were asked to circle the region which they felt best represented the padparadscha color range. Judging from the results above, it is clear that even among experienced observers there is little agreement as to the color range of this gem variety.

Admittedly this survey was far too small to be meaningful. However two things were clear from the responses. Experienced sapphire dealers do not agree on the color range of padparadscha and they do not include only pastel colors. This makes the crafting of a definition by a group such as the LMHC devilishly difficult.

The ownership of words

Daydream for a moment. Imagine if you will a meeting of international wine makers where standards are discussed. After much debate, a consensus is reached on the definition of “champagne.”

A noble goal, I think we will all agree. But also imagine the situation if that meeting did not include a voting member from France? And what if the definition agreed upon was so narrow that it excluded the finest vintages from France’s Champagne district?

We have a similar situation today with the rare and lovely sapphire variety of padparadscha, where not a single representative from Sri Lanka was present while a Sri Lankan word was being defined. This begs the question of who owns a word. Is it those from whose tongue it originates, or the collective masses around the world? Can we really define a word while not allowing a vote to those from whose language it has sprung?

Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Along with the crystal in Figure 3, this 30-ct. padparadscha from Sri Lanka was cited by Robert Crowningshield as the epitome of the variety.

Photo © Tino Hammid.

Coincidentally, as I was pondering this issue back in 2005, I chanced upon an essay in the New York Times discussing the English dictionary of Samuel Johnson published some 250 years ago. The essay’s author Jack Lynch had this to say:

Johnson approached each entry with the same overarching question: What does a word mean? You can answer this question many ways. You can turn to Latin roots, consult a committee of authoritative scholars, or follow logical principles about things like double negatives.

But Johnson’s answer was simpler: a word means whatever the best writers say it means. He was convinced that no one — no emperor, no king and certainly no dictionary writer — had the authority to rule on meanings. Our language is the common property of all who have used it, and meanings come not from fiat but from precedent.

So before writing his definitions, Johnson spent years reading the great authors of the English tradition. And it is these (mostly) men who did the real work: they told him what the words meant, and he in turn told us. They are the ones who “fixed” the language, and what is often called a tremendous act of egotism on Johnson’s part in fact becomes one of humility.

– Jack Lynch, Dr. Johnson’s Revolution, New York Times, 2 July, 2005

In the previous passages, I have cited a number of Sri Lankan and Indian sources, both historic and contemporary, giving a definition of padparadscha that differs in important respects with that developed by Robert Crowningshield (and followed today in modified form by the LMHC).

Which brings me back to the original question. Who owns a word?

Language is a vital part of any culture. While the efforts of bodies such as the LMHC are to be lauded, before they dive into the sun-kissed waters of padparadscha, I believe it would behoove them to do as Samuel Johnson. Read the great authors of the past. And consult the great minds of the present. There is a vast body of Eastern gem literature that has hardly been touched by gemology, along with a number of fine Sri Lankan scholars, gem dealers and gemologists that would be delighted to help us. Let’s dip into it.

At the same time, all of us in the gem trade, both gemologists and dealers, need to understand that words like padparadscha and pigeon's blood were never precisely defined in the past and nor is there general agreement in the present. Thus we need to ask the question: Is a consumer better served by a precise, but arbitrary definition of something as nebulous as padparadscha? Or should we do as we have already done with the definitions of ruby, blue sapphire and emerald and literally let a thousand flowers bloom? Is anyone harmed by embracing a wonderful linguistic artifact in the greatest possible way?

Think about it. The definition of blue sapphire encompasses a huge space. From the lightest of blues, through the most vivid, to stones that are effectively black. Not a single lab in the world has ever refused to call a sapphire a sapphire because of its color zoning, tone or saturation. So why is padparadscha singled out for special treatment? Has their been a rash of consumers cheated by this? We have good blue sapphires and not so good ones. Why shouldn't the gem world be allowed both good and bad padparadschas?

In examining this question, I believe we will better understand how to define words like ruby, sapphire, emerald and, dare I say it, paraíba. And in the process, we might just give the Sri Lankans back the ownership of their word. I know they will thank us.

Figure 13.

Figure 13.

The variety of nature With both lotus flowers and sunsets, there is a range of possibilities. Since padparadscha is defined by these colors, thus it seems logical that padparadscha might also cover a range of possibilities. Sunset photo at Bagan, Myanmar: Richard W. Hughes; lotus photo: iStockphoto.com

… …

|

Keferstein’s Mineralogia Polyglota b. Unser Rubin. Der Name Rubin kommt nicht im Alterthume und Orients vor; erst im Mittelalter, (um das Jahr 1300) findet sich der Name rubinsus, rubies, Robins; woher derselbe stammt, ist zweifelhaft, ob von dem persischen rutbi, der eine Art des benefch war (s. diesen), oder von der rotten Farbe (euer im Lateinischen, rudhir im Sanskrit, rhudd im Keltischen und ähnlich in den meisten Sprachen). Der Name balais, Rubinbalais stammt von balaschsch der Araber (s. balchasch), der unser Spinell gewesen sein wird. Po-ma-lo-kia im Chinesischen; moey heissen di rotten Edelsteine im Allgemeinen. manikja im Sanskrit, auch padmaraga (d. i. lotosfarbig, rosenrot), mahamulga (kostbarer Stein, patalopala (blassrother Edelstein), arunopala (dunkelroter), conitopala (Rother), lohito (der Rothe), conaratna, tanariratna (Sonnenwedelstein), kuruwilla, kuruwila, kuruwinda, lakshmipusha; alle diese — meist wohl dichterische — Namen übersetzt Wilson in seinem Wörterbuch mit Rubin, doch mögen auch hierunter andere Rothe Edelsteine begriffen seyn, die mit kuru anfangenden Namen erinnern an Korund, korundun in Indien. Im Tibetanischen finde ich im Wörterbuche von Körös keinen Namen für Rubin angeführt, obwohl man den Stein sehr wohl kennen muss; vielleicht gehört hierher mani (Edelstein), wegen des Zusammenhanges mit manik, auch mya-mena-phyena ein rother Edelstein. manik, manika, auch tokes im Hindu; — manika, manikük, manikür, auch maha mülya (d. i. von hohem Werte), padmaraga, padmaragamani im Bengalischen; — manikan, padma, padam im Malaiischen; — pata-mra im Malabarischen, auch kyaokoi (d. i. Rotstein) und eiliges chogeppi; — lankaratte im Ceylonesischen. – Christian Keferstein, Mineralogia polyglota, 1849 |

References and further reading

While doing research for my first book (Hughes, 1990), the late, great John Sinkankas gave me a valuable bit of advice, suggesting I concentrate on first-person accounts, rather than those whose knowledge of a subject came via distant sources. Since that day I have spent great effort (and more than a little coin) in locating Asian sources of information on this most Asian of precious stones – corundum. Below are a few gems of early corundum literature, along with other works of interest on padparadscha.

- Beruni, M.i.A., al- (1989) The Book most Comprehensive in Knowledge on Precious Stones: al-Beruni’s Book on Mineralogy [Kitab al-jamahir fi marifat al-jawahir]. One Hundred Great Books of Islamic Civilization, Natural Sciences No. 66, Islamabad, Pakistan Hijra Council, edited by Hakim Mohammad Said, 355 pp.

- Crowningshield, R. (1983) Padparadscha: What’s in a name? Gems & Gemology, Vol. 19, No.1, pp. 30–36.

- Dick, G. (1992) The power of padparadscha. JewelSiam, Vol. 3, No. 4.

- Emmett, J.L., Scarratt, K. et al. (2003) Beryllium diffusion of ruby and sapphire. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 39, No. 2, Summer, pp. 84–135.

- Ferguson, A.M. and Ferguson, J. (1888) All About Gold, Gems and Pearls in Ceylon and Southern India. Colombo, London, A.M. and J. Ferguson, 2nd edition, 428 pp.

- Finot, L. (1896) Les Lapidaires Indiens. Paris, Librarie Émile Bouillon, Éditeur, reprinted by Adidom, Paris, 1986, 280 pp.

- Fryer, C. (1986) Gem Trade Lab Notes: Sapphire, pinkish-orange (“Padparadscha”). Gems & Gemology, Vol. 22, No. 1, Spring, pp. 52–53.

- Gunaratne, H.S. and Dissanayake, C.B. (1995) Gems and Gem Deposits of Sri Lanka. Colombo, National Gem and Jewellery Authority of Sri Lanka, 1st ed., 203 pp.

- Henn, U. and Bank, H. (1992) On the distinction between yellow corundum/“padparadscha”/rubies. Börsen Bulletin, 3/92, p. 226.

- Holland, T.H. (1898) A Manual of the Geology of India—Economic Geology: Corundum. Calcutta, Geological Survey of India, 2nd ed., Pt. 1, 79 pp.

- Huda, S.N.A. (1998) Arab Roots of Gemology: Ahmad ibn Yusef Al Tifaschi’s Best Thoughts on the Best of Stones. Lanham, MD, Scarecrow Press, 272 pp.

- Hughes, R.W. (1990) Corundum. Butterworths Gem Books, Northants, UK, Butterworth-Heinemann, 314 pp.

- Hughes, R.W. (1997) Ruby & Sapphire. Boulder, CO, RWH Publishing, 512 pp.

- Hughes, R.W. (2002) Walking the line in ruby & sapphire. The Guide, Vol. 21, Issue 4, Part 1, July–Aug., pp. 4–8.

- Jomard, C. (1996) Le Saphir Padparadscha. Université de Nantes, Nantes, France, 64 pp.

- Johnson, M.L. and Koivula, J.I. (1997) Gems News: Orange sapphire and other gems from the Tunduru region. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 33, No. 1, Spring, p. 66.

- Keferstein, C. (1849) Mineralogia polyglotta. Halle, Gebauersche Buchdruckelrei, 248 pp.

- LMHC (2010) Padparadscha sapphire. Information Sheet #4, 1 p.

- Lynch, J. (2005) Dr. Johnson’s revolution. New York Times, July 2, 2005, p. A27.

- Murthy, S.R.N. (1990, 1993) Gemmological Studies in Sanskrit Texts: English Rendering with notes on Gemmology in Five Sanskrit Texts. Bangalore, N. Subbaiah Setty, 2 Vols., (Vol. 2: Trichur: Foundation for the Advancement of Ancient Indian Science, Technology, and Tradition), 103, 97 pp.

- Notari, F. (1996) Le saphir padparadscha. Diplôme d’Université de Gemmologie de Nantes, 95 pp.

- Notari, F. Le saphir padparadscha. Revue de Gemmologie AFG, 1997, No. 132, pp. 24–27, not seen.

- Pisutha-Arnond, V., Häger, T. et al. (2004) Yellow and brown coloration in beryllium-treated sapphires. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 29, No. 2, April, pp. 77–103.

- Sarma, S.R. (1984) Thakkura Pheru’s Rayanaparikkha: A Medieval Prakit text on Gemmology. Aligarh, India, Viveka Publications, 84 pp.

- Scarratt, K. (2002) Is it pink or is it padparadscha? Rapaport, Vol. 25, pp. 103–109; not seen.

- Schmetzer, K. and Schwarz, D. (2004) The causes of colour in untreated, heat treated and diffusion treated orange and pinkish orange sapphires – a review. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 29, No. 3, July, pp. 149–181.

- Shastri, J.L., ed. (1978) Garuda Purana. English translation 1978, Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass, Vol. 12, Part 1, see pp. 224–246.

- Shukla, M.S. (1972) A History of Gem Industry in Ancient & Medieval India (Part I—South India). Varanasi, Bharat-Bharati, 67 pp.

- Tagore, S.M. (1879, 1881) Mani-Málá, or a Treatise on Gems. Calcutta, I.C. Bose & Co., 2 Vols., 1046 pp.

- Wojtilla, G.Y. (1973) Indian precious stones in the ancient east and west. Acta Orientalia Hungaricae, Vol. 27, No. 2, pp. 211–224.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank all those who participated in the padparadscha survey. Special thanks to Bill Larson and John Emmett for discussions on the subject and review of the manuscript, along with Sheriff Rahuman for pointing out the difference between tumeric and true saffron and Gamini Zoysa for introductions in Sri Lanka. And a big thanks to my wife, Wimon Manorotkul, my daughter Billie, my niece Pin Manorotkul and my friend, Julie Poli, for putting up with the frequent lotus stops throughout our 2012 travels through Serendib. I still don't have the perfect Sri Lankan lotus photo, but I'm a lot closer than before. For images of that visit, see our Shooting Galleries. Finally, a huge thanks to Ken Scarratt of the GIA in Bangkok, for bringing me up to speed on the discussions and deliberations involved with the LMHC definition.

About the author

Richard W. Hughes is one of the world’s foremost experts on ruby and sapphire. The author of several books and over 170 articles, his writings and photographs have appeared in a diverse range of publications, and he has received numerous industry awards. Co-winner of the 2004 Edward J. Gübelin Most Valuable Article Award from Gems & Gemology magazine, the following year he was awarded a Richard T. Liddicoat Journalism Award from the American Gem Society. In 2010, he received the Antonio C. Bonanno Award for Excellence in Gemology from the Accredited Gemologists Association. The Association Française de Gemmologie (AFG) in 2013 named Richard as one of the Fifty most important figures that have shaped the history of gems since antiquity. In 2016, Richard was awarded a visiting professorship at Shanghai's Tongji University. 2017 saw the publication of Richard and his wife and daughter's Ruby & Sapphire • A Gemologist's Guide, arguably the most complete book ever published on a single gem species and the culmination of nearly four decades of work in gemology. In 2018, Richard was named Photographer of the Year by the Gem-A, recognizing his photo of a jade-trading market in China, while in 2020, he was elected to the board of directors of the Accredited Gemologists Association and was appointed to the editorial review board of Gems & Gemology and The Australian Gemmologist magazine. Richard's latest book, Jade • A Gemologist's Guide, was published in 2022.

Notes

The first draft of this article was written in 2005, while I was working at the AGTA-GTC. Finished off later with a bit of prodding from John Emmett, and still later modified following comments from Ken Scarratt. I have published it in the hope that the LMHC will revisit their definition of padparadscha.