Is the Mozambique stone the bejesus of bird's blood? Lotus Gemology's resident ruby wallah, Richard Hughes, weighs in on the state of the market and how Mozambique stacks up to historical heavyweights like Burma and Thailand/Cambodia.

You see that real ruby red and oh, it does something to you. I think those of us in this business are in love with the stones we're dealing with. It's nature's finest creation; there's just something about it. I'd like to own a fine Burmese ruby just to gaze upon it. It's not the value. If I wanted the value, I'd just buy a ton of gold.Richard Hughes to journalist Rod Nordland in 1982

Further downtown

23 March 2015—In the autumn of 2007, I spent a month in East Africa, visiting gem dealers and mines in Kenya and Tanzania. The principle aim was to explore the sapphire mines of southern Tanzania at Songea and Tunduru and the spinel mines of Mahenge (described in Downtown) for an updated edition of my book, Ruby & Sapphire, but my team also visited the tanzanite mines at Merelani (detailed in Working the Blueseam).

While in southern Tanzania's Tunduru district, we witnessed a number of miners crossing the Muhuwesi river that separates Tanzania from Mozambique. Just a few short months later, it became clear why. Ruby had been discovered in Mozambique.

Flash forward to 2009. My close friend, Vincent Pardieu, who I had asked to join me on the 2007 journey, was now working as the GIA's first field gemologist. His job? Hunt down ruby and sapphire, wherever it might be found.

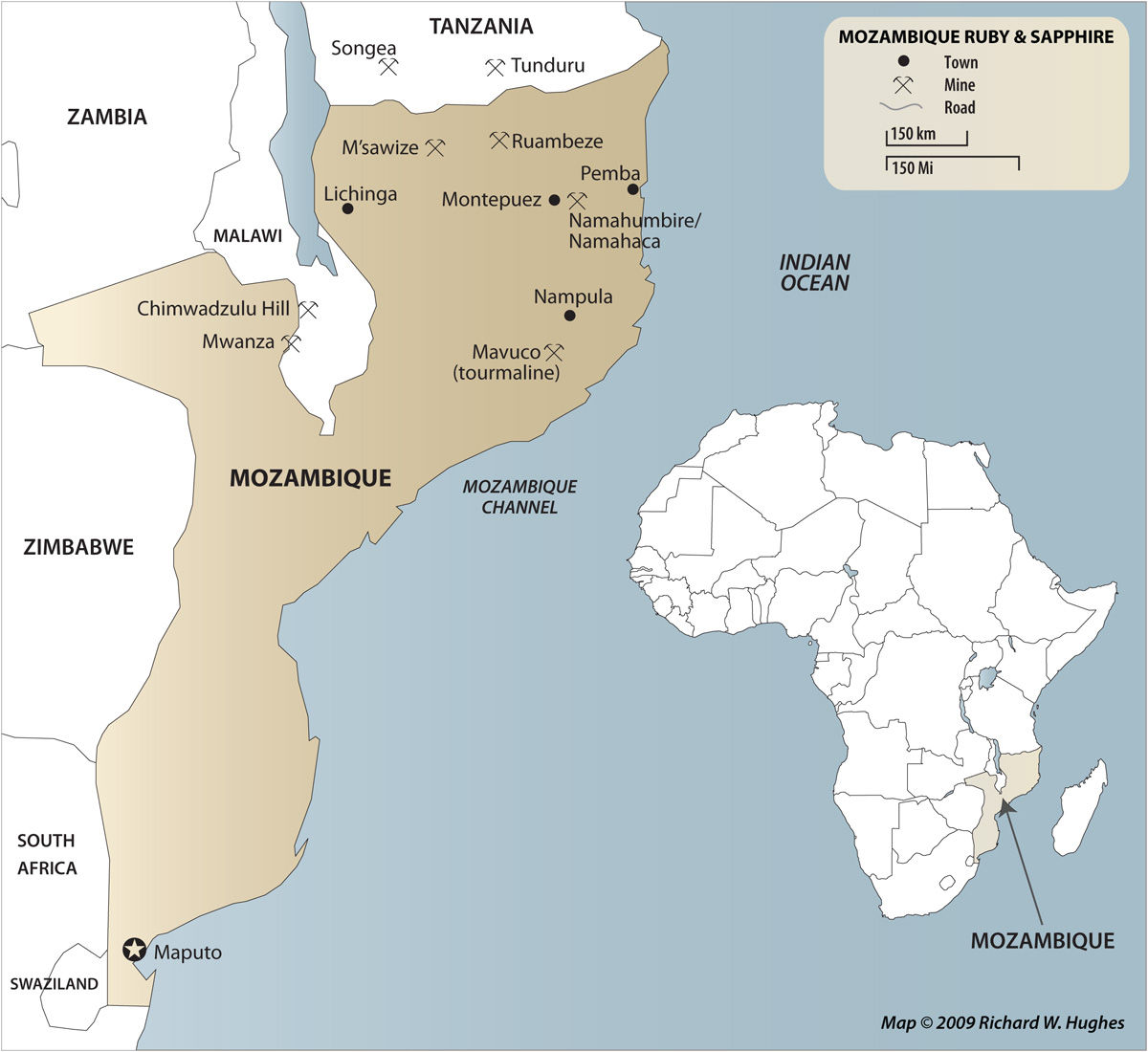

Map of Mozambique, showing the location of the ruby mines near Montepuez. Click on the map for a larger version.

Map of Mozambique, showing the location of the ruby mines near Montepuez. Click on the map for a larger version.

Gimme danger

Shortly after the discovery of ruby in Mozambique, Pardieu visited two different locales (M'sawize and Ruambeze). But the prize location, Namahumbire, just near Montepuez, remained out of reach. Vince has often said to me (with his wry smile) that he does not like "unfinished business." Thus Vince and I, with my old travel buddy, Mark Smith, found ourselves touching down at Pemba, Mozambique in December 2009, desperately seeking to scratch yet another mine off our ever-expanding bucket list.

We had no idea what lay ahead. I personally think Vince invited me along because he thought it would be an easy trip and I wouldn't complain too much. The food would be good, we would not have to hike through mud and, if I flashed a copy of my book, it might provide just the entrée needed. But more importantly, as there would be no rat-infested hovels where we slept, I could not poke fun at him regarding his rodent phobia. Similarly, because there would be no creaky bridges to cross, he could not tease me in the same way. So we would do a trip on neutral ground. These were the best laid plans involving mice, and a man with acrophobia.

Mark Smith (left) and Vincent Pardieu (center), who arrived with the author at Pemba, Mozambique in December 2009. Photo: Richard Hughes/Lotus Gemology. Click on the image for a larger view.

Mark Smith (left) and Vincent Pardieu (center), who arrived with the author at Pemba, Mozambique in December 2009. Photo: Richard Hughes/Lotus Gemology. Click on the image for a larger view.

We arrived in Pemba in good condition, but the entry was not without its quirks. Visa-on-arrival was available, but apparently returning-change-when-paying-with-large-note-for-visa-on-arrival was not. It took serious effort to recover my money before we could exit the airport.

Roughing it abroad. Vincent Pardieu enjoys a small lobster in Pemba. Photo: Richard Hughes/Lotus Gemology. Click on the image for a larger view.

Roughing it abroad. Vincent Pardieu enjoys a small lobster in Pemba. Photo: Richard Hughes/Lotus Gemology. Click on the image for a larger view.

Pemba is a wonderful place. Sitting astride the Indian Ocean, it has beautiful beaches and terrific seafood. Mark and I made the best of our downtime while Vince negotiated for access to the mines. Vince chatted with officials; Mark and I went diving. It was one of my more pleasant mining trips.

Richard Hughes discovers that even the starfish like rubies. Photo: Mark Smith. Click on the image for a larger view.

Richard Hughes discovers that even the starfish like rubies. Photo: Mark Smith. Click on the image for a larger view.

To the mines!

Following several days of negotiations in Pemba, the owner of the property consented to allow us a visit. The next day, we drove down towards Montepuez, but not without incident. Shortly before turning off the main road, a bicycle swerved directly in front of us. Having your life appear before your eyes doesn't begin to describe the scene. Our driver swerved and miraculously did not run over the bicyclist. But that set us careening directly into a local market packed with people. We ended up halting less than a meter from disaster. Getting out, our driver apologized to the stunned onlookers, and then got back on the road towards the mines, still shaking from this close encounter with death-by-mob.

Garimpeiros (independent prospectors) on the road to the ruby mines in the bush near Montepuez, Mozambique, December 2009. Photo: Richard Hughes/Lotus Gemology. Click on the image for a larger view.

Garimpeiros (independent prospectors) on the road to the ruby mines in the bush near Montepuez, Mozambique, December 2009. Photo: Richard Hughes/Lotus Gemology. Click on the image for a larger view.

Arriving at the site, we were told that the unlicensed miners had been pushed out. The cooking utensils laying about suggested their exit had been both recent and hasty. What was most remarkable was what else they had left behind. Amidst the coal-black embers we discovered red fire everywhere. That was ruby and this was about to become the world's richest ruby mine.

Upon our arrival at the site, we found ruby everywhere on the ground and were able to collect a significant number of samples in just minutes (inset photo), more so than at any other ruby mine I had ever visited. Photo: Mark Smith; inset photo: Richard Hughes/Lotus Gemology. Click on the photo for a larger view.

Upon our arrival at the site, we found ruby everywhere on the ground and were able to collect a significant number of samples in just minutes (inset photo), more so than at any other ruby mine I had ever visited. Photo: Mark Smith; inset photo: Richard Hughes/Lotus Gemology. Click on the photo for a larger view.

Upon our arrival back in Pemba that night, I put in a call to a friend in Hong Kong. When he picked up the phone, I told him I had just visited the world's richest ruby deposit and the owner was looking for an investor. He asked me where I was. Mozambique, I said. "That's Africa, isn't it?" Yes, I said. "I'm afraid to put money into a mine in Africa," he replied.

After my return to Bangkok, I called another friend, this one with experience mining gems in Africa. After listening to my tale, he took his geologist to Mozambique, surveyed the property and came to the same conclusion as me. But try as he might, he could not raise the financing.

Two up, two down. In their wake, Gemfields successfully negotiated a lease for a huge chunk of the deposit and are now into full production—and it's raining rubies.

Let me say this. Mozambique ruby is not just about Gemfields. While Gemfields has the largest concession, there are other companies with leases and hundreds, if not thousands of garimpeiros who are bringing the stone to market. When it comes to the Montepuez deposit, think big. It's like Mogok or Madagascar. Far too much for any single company. My guess is that Gemfields' production represents less than half of all the stones in the market, and it could be much less than that.

Red gold from Mozambique

Red gold from Mozambique

rough to cut Top from left: 15.79, 19.77 and 22.30 ct rough.

Middle: Preforms from the same rough (9.30 ct and right 14.29 ct).

Bottom from left: Cut stones from the same rough (8.52, 8.41 and 13.22 ct, giving 54%, 43% and 60% yields respectively).

These are extraordinarily high yields, attesting to the quality of the rough stone. Photos: Wimon Manorotkul/Lotus Gemology. Gems: Sukhadia Stones, Bangkok. Click on the images for a larger view.

Mozambique ruby: Elvis is in the building

For much of human history, the only two major producers of ruby were Sri Lanka and Mogok (Burma). In the 19th century, the now-exhausted mines along the Thai/Cambodian border also began production. Since then, East Africa and Madagascar have shown great promise, but deposits have either been quickly depleted (Winza, Vatomandry, Matombo), or have not produced enough facet quality (John Saul, Penny Lane). As for the various marble-based deposits formed from the India-Asia collision (Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Pakistan, Nepal, Vietnam & China), none have produced enough clean material over a significant period of time.

The Mozambique deposit near Montepuez has now joined an elite club. In just six years, an unprecedented quantity of fine stones has entered the market in almost unheard-of sizes. Ten years ago if you asked me to source a ten-carat ruby, I might have come up with one or two decent stones. Might. Today I can find a dozen or more.

What this means for the market is incredible. It allows ruby to be used in previously unheard of ways. If I were a designer, I would be over-the-moon ecstatic.

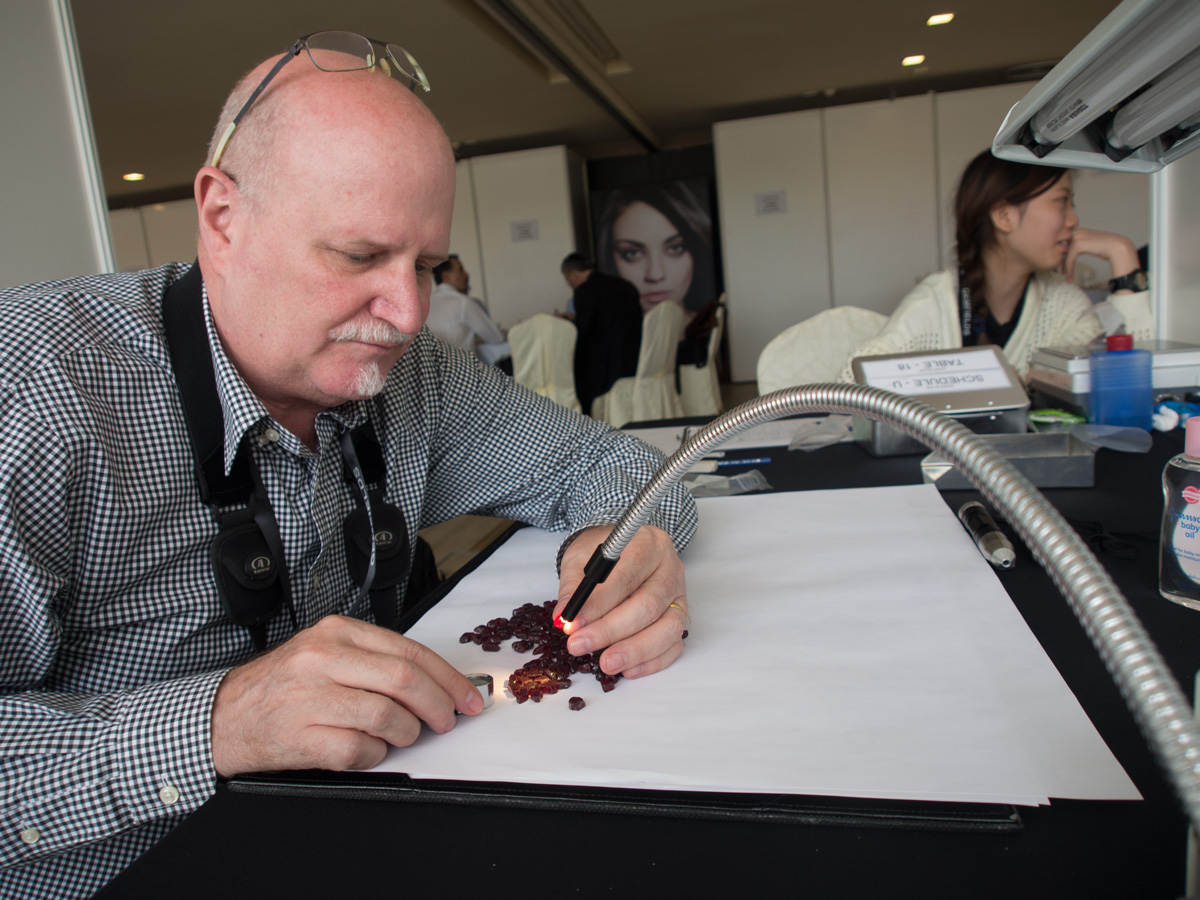

Lotus Gemology's Richard Hughes examining a lot of rough Mozambique ruby at Gemfields' December 2014 Singapore auction. Photo: E. Billie Hughes/Lotus Gemology. Click on the image for a larger view.

Lotus Gemology's Richard Hughes examining a lot of rough Mozambique ruby at Gemfields' December 2014 Singapore auction. Photo: E. Billie Hughes/Lotus Gemology. Click on the image for a larger view.

Should I buy Mozambique ruby?

Let me state the following with the utmost clarity. My crystal ball broke just prior to publication. So you are on your own. But…

…if this deposit proves to be short-lived, in a couple decade's time we will all be looking back saying "I was there during the glory days. I was so there!"

…and if Mozambique continues to produce at the same rate it has since 2009, we will all be looking back and saying "Thank god(s) for Mozambique ruby."

Why? Many believe that if a gem becomes too plentiful, prices will drop. Tell that to those who waited for sapphire prices to drop when Kashmir sapphires first entered the market in the 1880's. Tell that to those who waited on Paraíba tourmaline during the 1980's.

I'll never forget a story a close friend once told me. He made a trip to Brazil in search of alexandrite, which at that time was pouring out of Hematita, in Minas Gerais. In the park at Teófilo Otoni, where many gem dealers and brokers held court, someone showed him a stone that blew his mind. He quickly phoned his wife and asked her to wire him $100,000. She said "Oh, you found the alex?" No, honey, I'm buying tourmaline. Her reply is unpublishable. But he convinced her and eventually ended up with an oil drum full of Paraíba rough. Just guess what that's worth now.

Weighing in at a massive 40.22 ct, the "Rhino ruby" was auctioned at Gemfields' December 2014 Singapore sale. It was the largest fine ruby mined by Gemfields to date. Photo: E. Billie Hughes/Lotus Gemology. Click on the photo for a larger image.

Weighing in at a massive 40.22 ct, the "Rhino ruby" was auctioned at Gemfields' December 2014 Singapore sale. It was the largest fine ruby mined by Gemfields to date. Photo: E. Billie Hughes/Lotus Gemology. Click on the photo for a larger image.

Bangkok's Por Kuang Tang examines the Rhino ruby at Gemfields' December 2014 auction in Singapore. Photo: E. Billie Hughes/Lotus Gemology. Click on the photo for a larger image.

Bangkok's Por Kuang Tang examines the Rhino ruby at Gemfields' December 2014 auction in Singapore. Photo: E. Billie Hughes/Lotus Gemology. Click on the photo for a larger image.

Auction inaction

A number of dealers have told me that the major auction houses have resisted offering Mozambique rubies. Why? Because there is no history. They prefer to wait it out.

That's like waiting until Warhol to admit that Rembrandt knew his way around a paintbrush.

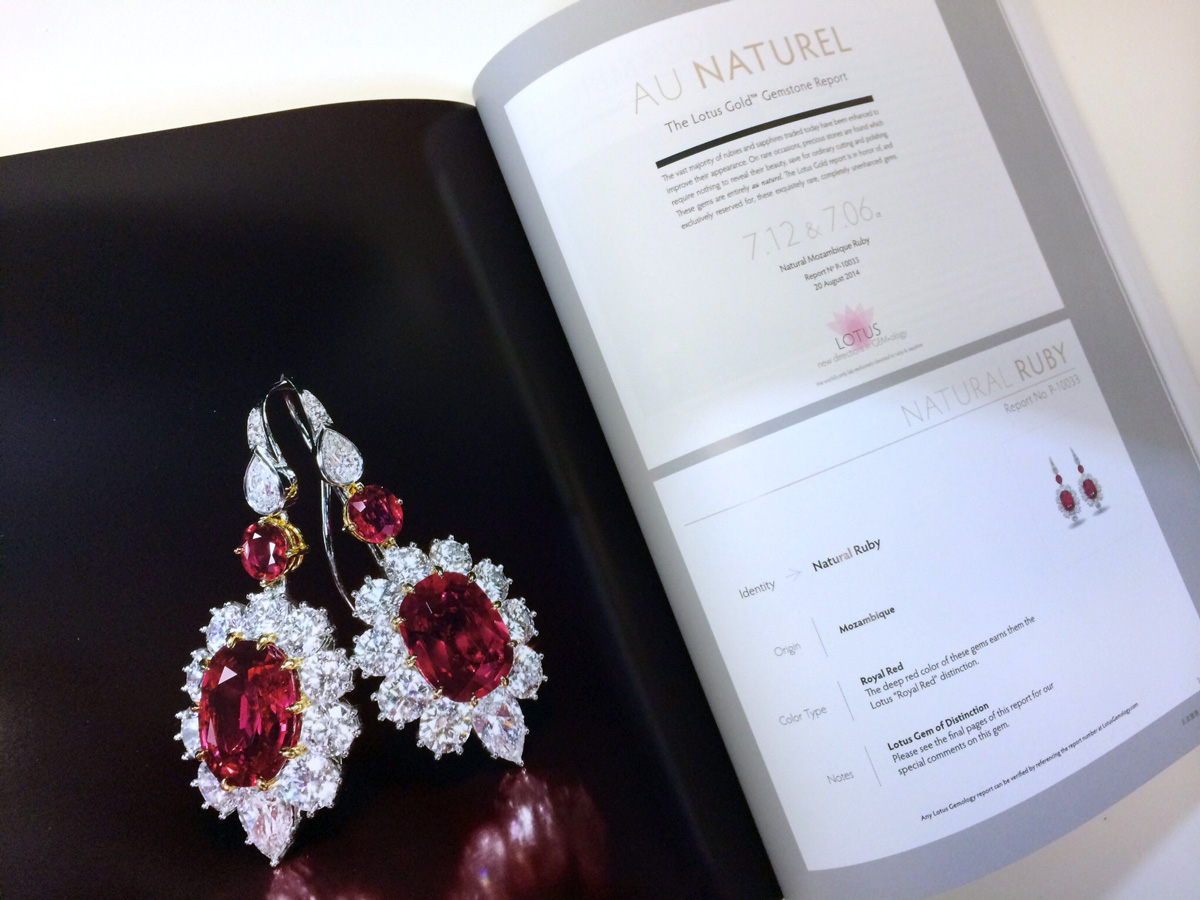

In any event, it has created opportunities for others, who are rushing to fill the void. Tiancheng International sold a matched pair of Mozambique ruby earrings featuring two 7 ct stones for US$1.7 million in December 2014.

Lotus Gemology's Gold Report featured prominently in the auction catalog for the sale of this matched pair of 7 ct Mozambique rubies by Tiencheng International. These sold for US$1.7 million in December 2014. Click on the photo for a larger image.

Lotus Gemology's Gold Report featured prominently in the auction catalog for the sale of this matched pair of 7 ct Mozambique rubies by Tiencheng International. These sold for US$1.7 million in December 2014. Click on the photo for a larger image.

Pigeon-holing pigeon's blood (Burmese: kho thwe)

I have written a lot about pigeon's blood in the past (Hughes, 1990, 1996, 1997). It is one of those glorious concepts that conjures up spectacular visions and yet is impossible to pin down. How so? Let's take a quick look at the historical record.

The first recorded appearance of the term "pigeon's blood" ruby in the English language I have located is from the 1839 catalog of the Hope collection:

A superlatively fine Oriental ruby, of an ovate octagonal form, very spread, and cut on the surface with step facets; it is of a pigeon blood-colour, and of the purest tint; free from any flaw or defect whatever; and though not of a perfect shape, it may, on account of its perfection in colour and transparency, be put among the "Pierres d'échantillon." It is set as a ring with small roses. Bram Hertz, 1839, A Catalogue of the Collection of Pearls and Precious Stones formed by Henry Philip Hope, Esq.

From this date on, references to "pigeon's blood" are frequent, and yet none of the sources describe what the actual color is. It is not until the 20th century that we find an actual definition of pigeon's blood red. And when we do find such references, guess what? They do not agree. Witness the following from two authorities writing in the 1930's:

The most prized colour in a ruby is what is commonly termed pigeon’s blood, a term of Chinese origin, the colour being likened to the two spots of blood which appear at the nostrils of a freshly killed pigeon. The descriptions of this colour as being that of fresh arterial blood, or of the centre red ray of the solar spectrum are not correct and therefore misleading; it may perhaps best be described as a deep bright carmine without the slightest trace of visible blue, and very closely resembles the colour of a good clear red currant jelly. It may be said at once that this colour is of the greatest rarity, and is only accurately known to a very few people; which accounts for the many people who regard themselves as being authoritative experts on rubies utterly failing to recognise it when they do see it. It is therefore most decidedly the work of a thoroughly experienced expert to decide what is really true pigeon’s blood colour and what is not.

Under the dichroscope, stones of this colour will show two distinct shades of red, that of the ordinary ray being the lightest. Blue or any trace of it will be entirely absent. It must, however, be noted that twin colours of red alone do not of necessity indicate that the colour of the stone is the true pigeon’s blood, as other grades of colour will also produce the same effect; but if the faintest trace of blue is detectable it is at once decisive that the colour is not true pigeon’s blood, however near to it the appearance may be.

The term pigeon’s blood is commonly stated to be of Burmese origin, but such is not the case as it has no significance to them, neither do they recognise or use it. It is of very great antiquity, and undoubtedly originated with the Chinese in the very early days when they owned the present Burmese ruby mining area.

— J.F. Halford-Watkins, 1934, The Book of Ruby & Sapphire

Yet another experienced observer, J. Coggin Brown, had a very different take:

…the clear, limpid, deep crimson red of the Mogok ruby is incomparable. The shade which is most admired is a transparent carmine-red with a suggestion of a bluish tinge which gives the famous 'pigeon's blood' stone. (The term is derived from the Hindustani, the Indian lapidaries comparing a faultless ruby with the blood-red colour of a living pigeon's eye.)

— J. Coggin Brown, 1936, India's Mineral Wealth

The Crimson Prince is a 3.32 ct Mogok ruby that displays the quintessential pigeon's blood color. As you can see from the previous photos, the finest Mozambique rubies can have colors quite similar to Burma's finest. Photo: Jeff Scovil. Gem: Jeffrey Bergman

The Crimson Prince is a 3.32 ct Mogok ruby that displays the quintessential pigeon's blood color. As you can see from the previous photos, the finest Mozambique rubies can have colors quite similar to Burma's finest. Photo: Jeff Scovil. Gem: Jeffrey Bergman

Does the new Mozambique ruby have a pigeon's blood red color? Given the above, I think that's the wrong question. We should be asking if Mozambique ruby can resemble the best from Burma. In my opinion, that's a qualified yes.

The recently deceased trader, W.K. Ho, once told me that the best Burma ruby was one that looked like a Thai ruby and the best Thai ruby was one that looked Burmese. What he meant was that it was rare to find a Mogok stone that was pure red. Most tend towards purple. Similarly, it was hard to find a Thai ruby that looked Burmese, as they were missing the silk and strong red fluorescence of the Mogok stone.

Mozambique ruby has silk. It also has more iron than the Burma stone, which shifts the color away from purple to more of a straight red. That iron does quench the fluorescence a bit, but there is not as much as we find in Thai/Cambodian rubies. So the Mozambique stone is somewhere in between a mixture of the best features of each, a Thai ruby that appears Burmese, a Burmese ruby that appears Thai.

One major difference between Burma and Mozambique is the strength of color. The color of Mogok stones tends to improve with size, whereas the Moz ruby's sweet spot is in the smaller end of the range, with stones of ten carats or more tending to go a bit dark. Of course Mogok rubies of large size are practically impossible to find as most are full of cracks.

In the end, when it comes to pigeon's blood, I like what the rebel Shan State Army's ruby broker told journalist Rod Nordland back in 1982:

We asked to see a stone the color of pigeon blood, the most valued of Burmese reds, the epitome of the great Mogok ruby. No one had one. "Asking to see the pigeon blood," said Khun Cha with a shrug, "is like asking to see the face of God." Rod Nordland, 1982, On the Treacherous Trail to the Rare Ruby Red

While color type terms can serve as a useful guide for newcomers, providing a crude map through the wilderness, experienced buyers understand that such terms are subjective. As they buy and sell more, they learn to trust their own judgment. This is normal. In any market, one will find a variety of participants. Some are new and still learning, while others have more experience and sophistication in their judgment. A colored gemstone's appearance is dependent on many factors, not just the color. The idea that one could craft a single "correct" definition for a subjective term such as pigeon's blood is not supported by the historical record, nor should it be, since what one person decides is beautiful is heavily influenced by that person's history and experience.

In my experience, the most important lesson here is thus: Beauty and attraction are personal choices absolutely apart from grading systems or definitions. Pardon me for saying so, but these emotions cannot be "pigeon-holed."

Honestly, I can cite numerous references, both old and new, in support of what my opinion is on the definition of pigeon's blood. But that would be silly, as so few of the historical definitions agree with one another. Which brings us back to what I believe is the best position for a buyer. Don't fear emotion. Buy what your own eyes find attractive. Buy with your head and your heart.

Red rain

It's common for people to speak about things they have never seen. No one can have personal experience about everything, because no one can possibly visit every place and even if they could, their experiences would only represent their impressions at the exact time and location of their visit. Similarly, no one can look at every stone or read every book.

Experience is not just a function of places or gems seen, but also the perspective derived from those experiences, filtered through a lifetime's previous experiences and perspectives. We are all a product of our past. The following is my opinion, based on my lifetime's experiences and perspectives.

Over the previous three and a half decades I have visited almost every single major ruby mine on the planet. This includes many visits to the classic deposits of Burma, Sri Lanka and Thailand/Cambodia, along with others in Africa and Madagascar.

My entire adult life I've been involved with ruby. And as I write these words, I've never seen as much fine ruby as is now available, thanks to Mozambique.

Hand on heart, I've probably done more research on the history of ruby than not just anyone alive, but anyone who has ever lived. Based on my study of the historical record, when it comes to production of large, fine gems, there has never been a find of ruby as significant as what was discovered in Mozambique in 2009. Right now, it's raining ruby.

I stand outside, let the red rain splash me, let the rain fall on my skin. I'm bathing in red rain. Sell the gold, let the red rain splash you, let the rain fall on your skin…

Come out with me, defenses down, with the trust of a child.

References & further reading

- Brown, J.C. (1936) India’s Mineral Wealth. Calcutta, Oxford University Press, 1st ed., 335 pp.; RWHL.

- Halford-Watkins, J.F. (2012) The Book of Ruby and Sapphire. Hong Kong, RWH Publishing, [edited by Richard W. Hughes from a 1934 manuscript], 434 pp.; RWHL*.

- Hertz, B. (1839) A Catalogue of the Collection of Pearls and Precious Stones Formed by Henry Philip Hope, Esq. London, William Clowes and Sons, 112 pp., 42 plates; RWHL*.

- Hughes, R.W. (1990) Corundum. Butterworths Gem Books, Northants, UK, Butterworth-Heinemann, 314 pp., RWHL*.

- Hughes, R.W. (1996) Pigeon’s blood. Momentum, Vol. 4, No. 13, Dec. 1996-Feb. 1997, pp. 18–21; RWHL*

- Hughes, R.W. (1997) Ruby & Sapphire. Boulder, CO, RWH Publishing, 512 pp.; RWHL*.

- Nordland, R. (1982) On the treacherous trail to the rare ruby red. Asia, No. 3, September/October, pp. 34–41, 54–55; RWHL*.

- Prinsep, J. and Kalíkishen, R. (1832) Oriental accounts of the precious minerals. Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Vol. 1, pp. 353–363; RWHL*.

- Rees, A. (1819) Gems. In The Cyclopædia; or Universal Disctionary of Arts, Sciences, and Literature, London, Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, & Brown, 39 Vols., Vol. 15, see Gems; RWHL.

- Shastri, J.L., ed. (1978) Garuda Purana. English translation 1978, Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass, Vol. 12, Part 1, see pp. 224–246; RWHL*.

- Smith, H.G. (1896) Gems and Precious Stones. Sydney, Charles Potter, 87 pp.; RWHL.

- Streeter, E.W. (1892) Precious Stones and Gems. London, Bell, 5th edition, 355 pp.; RWHL*.

- Tagore, S.M. (1879, 1881) Mani-Málá, or a Treatise on Gems. Calcutta, I.C. Bose & Co., 2 Vols., 1046 pp.; RWHL*.

- Tennent, J.E. (1859) Ceylon: An Account of the Island, Physical, Historical and Topographical. London, Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts, 2 Vols., 702 pp.; RWHL.

About the author

Richard W. Hughes is one of the world’s foremost experts on ruby and sapphire. The author of several books and over 170 articles, his writings and photographs have appeared in a diverse range of publications, and he has received numerous industry awards. Co-winner of the 2004 Edward J. Gübelin Most Valuable Article Award from Gems & Gemology magazine, the following year he was awarded a Richard T. Liddicoat Journalism Award from the American Gem Society. In 2010, he received the Antonio C. Bonanno Award for Excellence in Gemology from the Accredited Gemologists Association. The Association Française de Gemmologie (AFG) in 2013 named Richard as one of the Fifty most important figures that have shaped the history of gems since antiquity. In 2016, Richard was awarded a visiting professorship at Shanghai's Tongji University. 2017 saw the publication of Richard and his wife and daughter's Ruby & Sapphire • A Gemologist's Guide, arguably the most complete book ever published on a single gem species and the culmination of nearly four decades of work in gemology. In 2018, Richard was named Photographer of the Year by the Gem-A, recognizing his photo of a jade-trading market in China, while in 2020, he was elected to the board of directors of the Accredited Gemologists Association and was appointed to the editorial review board of Gems & Gemology and The Australian Gemmologist magazine. Richard's latest book, Jade • A Gemologist's Guide, was published in 2022.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank all those who assisted in the research for this article (in alphabetical order): Paul Allan, Andrian Banks, Jeffery Bergman, Tony Brooke, Frankie Fong & Preeyamon Charoenrattanakhun, Jan Goodman, Puran Gurjar, Ian Harebottle, Gabriella Harvey, Hpone-Phyo Kan-Nyunt, Phuket Khunaprapakorn, Pichit Nilprapaporn, Vincent Pardieu, Julie Poli, Philippe Ressigeac, Dana Schorr, Santpal Sinchawla, Joginda Singh, Mark Smith, Chiku & Kaimesh Sukhadia, Por Kuang Tang, Veerasak & Tanyaporn Trirotanan. And finally, a nod to Peter Gabriel's "Red Rain."