The world sapphire market has changed dramatically in the past 40 years. The authors review the famous sources of the past and look at the current situation in sapphire around the globe.

World Sapphire Market Update • 2020

Among colored stones, blue sapphire has always been the most important in terms of sales. We provide this review to help jewelers, traders and appraisers to better understand this classic precious stone.

Classic sources (low-iron metamorphic)

During most of the 20th century, fine sapphire came from only three sources, Kashmir (India), Myanmar (Burma) and Sri Lanka (Ceylon). Thus, we will begin our essay with a discussion of these three.

Kashmir (India)

Sometime about 1881, a landslip high in the Indian Himalayas revealed blue sapphires of extraordinary quality. Ever since, the gem trade has salivated at the mere "ding" of the Kashmir bell. But by the late 1880s, the source had already gone dark. Beset with challenges of elevation, bad access and even worse politics, all subsequent attempts to work this storied deposit have been unsuccessful.

As of 2020, we don't really know exactly what a Kashmir sapphire is because the data pool is so badly polluted. While the stones of yore were evenly colored, nothing like that has been found at the mine since the original find. What are now sold and certified as "Kashmir" sapphires are based on "provenance," at a time when anything with the velvety blue "Kashmir" look, de facto became Kashmir. Thus 21st century "Kashmir" sapphires with bulletproof heritages from a century ago could actually be from Sri Lanka, which has occasionally produced stones of similar appearance. And in the modern era, many "Kashmir" sapphires first saw the light of day on the Red Island off the coast of East Africa. This fact has not stopped the market demand and, as we pen these words, stones with Kashmir walking papers from major labs can fetch as much as ten times the price of an identical stone from Madagascar.

So what does a fine Kashmir sapphire look like? It has a vivid blue with a slightly milky ('velvety') texture that holds the color under any light. This is the ideal against which all other sapphires are compared. Heated stones are seen on occasion, but usually of low quality.

Myanmar (Burma)

Burmese sapphires come from the Mogok Stone Tract and are famous for their "royal blue" color, which tends to be deeper/darker than the ideal blues from Kashmir. Unlike Kashmir, Mogok blues do contain rutile silk, and thus star sapphires are possible. Lighter blues are also found, as well as fancy colors, such as yellow, greenish blue, and violet/purple. Many Burmese sapphires are indistinguishable from sapphires from Sri Lanka, even with the most sophisticated testing. As of 2020, production from Mogok is diminishing, but still significant. Heated blues are seen, but rather rare compared with Sri Lanka.

Superb sapphire from Myanmar's Mogok Stone Tract, showing the classic "royal blue" color. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul/Lotus Gemology; specimen: Crown Color; click on a photo for a larger image

Superb sapphire from Myanmar's Mogok Stone Tract, showing the classic "royal blue" color. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul/Lotus Gemology; specimen: Crown Color; click on a photo for a larger image

Sri Lanka (Ceylon)

Ceylon is not just the oldest source of sapphire, with continuous production over 2000 years, but also has produced most of the large fine sapphires ever seen, with top stones ranging up to 500+ carats. As with Mogok stones, rutile silk is often present, resulting in star sapphires. Indeed, Sri Lanka and Burma are the only sources of high-quality star sapphires.

Sri Lankan blues tend to be a bit lighter and brighter in color than their Burmese brethren, but there is still much overlap between the sources. In many cases, labs cannot accurately separate blue sapphires from Sri Lanka and Burma. Additionally, it is extremely difficult to separate some Sri Lankan stones from those of Kashmir and Madagascar.

Top Sri Lankan blues are often compared to the color of the neck or tail feather of the peacock and are known in the trade as "peacock blues." They have what we call "snap," a slightly electric appearance (think cobalt blue spinel here). Medium to light colors are often termed "cornflower" blues, due to their resemblance to that flower. Many Ceylon sapphire are heat treated, but the trend today is definitely towards completely natural stones.

New sources

Madagascar

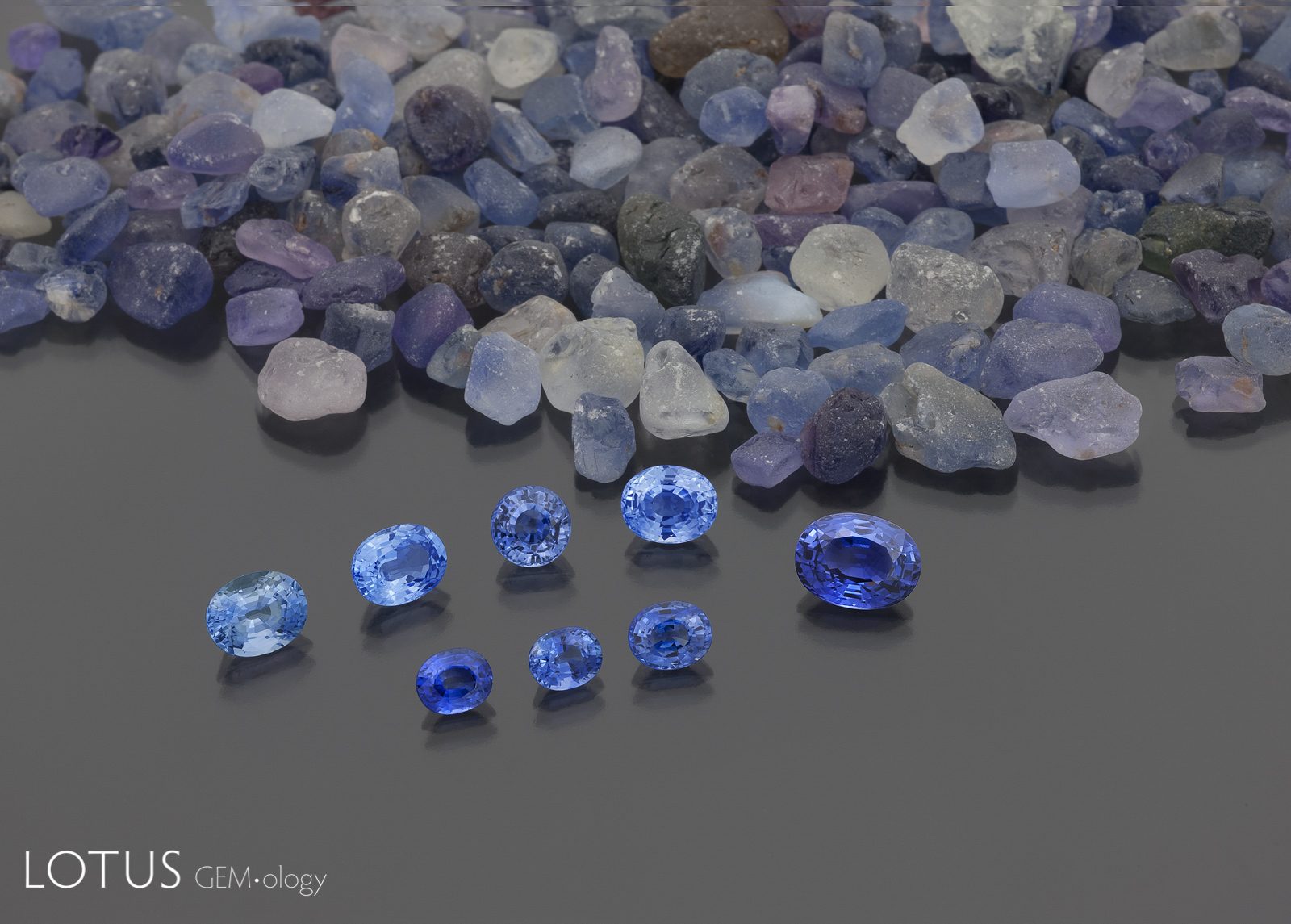

Beginning in the 1990s, fine sapphire first started to appear from Madagascar. It began in the deep south at Andranondambo, spread north to Ilakaka, and then moved further north to Didy and, in 2017, Bemainty. In some cases, Madagascar gems have velvet blues indistinguishable from Kashmir, while other cornflower and peacock blues resemble stones from Sri Lanka or even Burma. Rutile silk is only found in a small percentage of Madagascar blue sapphires. Thus star stones are generally not found.

As of 2020, Madagascar's production of fine blues is probably greater than both Sri Lanka and Burma combined. Most of the buying in Madagascar is done by Sri Lankan buyers and as the stones are taken to Sri Lanka for cutting and treatment, many of the blues now sold in Sri Lanka are actually from Madagascar. This misrepresentation of Madagascar origin is one of the major causes of disagreement between labs and their customers. That said, as the quality of Madagascar sapphire becomes better recognized, we are starting to see market prices move towards those from Ceylon.

Kashmir sapphire? Yes, the rough stones are from Kashmir. But the center 16-ct "velvet blue" stone is from Madagascar and shows just why Madagascar sapphire can blow with any blues on the bandstand. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul/Lotus Gemology; click on a photo for a larger image

Kashmir sapphire? Yes, the rough stones are from Kashmir. But the center 16-ct "velvet blue" stone is from Madagascar and shows just why Madagascar sapphire can blow with any blues on the bandstand. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul/Lotus Gemology; click on a photo for a larger image

Tanzania

While blue sapphires are found at Umba, Tanzania's major source of fine sapphire comes from the deep south in the Tunduru region, where world-class blues have been unearthed since 1994. Many of these are virtually indistinguishable from the gems from Sri Lanka, Burma and Madagascar.

Sapphire from Tanzania's Tunduru region showing the classic "cornflower blue" color range. Despite the high quality, you will almost never see a lab origin report stating the origin to be Tunduru. This is because the stones are virtually indistinguishable from Sri Lanka/Burma/Madagascar and, as a result, are almost always sold as being from one of the more famous sources. Virtually no lab has the resources obtain samples from all sources around the world and then characterize the different materials to the degree needed to produce accurate origin reports. Perhaps it is time for the trade to reexamine the entire premise of origin reports. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul/Lotus Gemology; specimens: World Sapphire; click on a photo for a larger image

Sapphire from Tanzania's Tunduru region showing the classic "cornflower blue" color range. Despite the high quality, you will almost never see a lab origin report stating the origin to be Tunduru. This is because the stones are virtually indistinguishable from Sri Lanka/Burma/Madagascar and, as a result, are almost always sold as being from one of the more famous sources. Virtually no lab has the resources obtain samples from all sources around the world and then characterize the different materials to the degree needed to produce accurate origin reports. Perhaps it is time for the trade to reexamine the entire premise of origin reports. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul/Lotus Gemology; specimens: World Sapphire; click on a photo for a larger image

Basalt-related sources

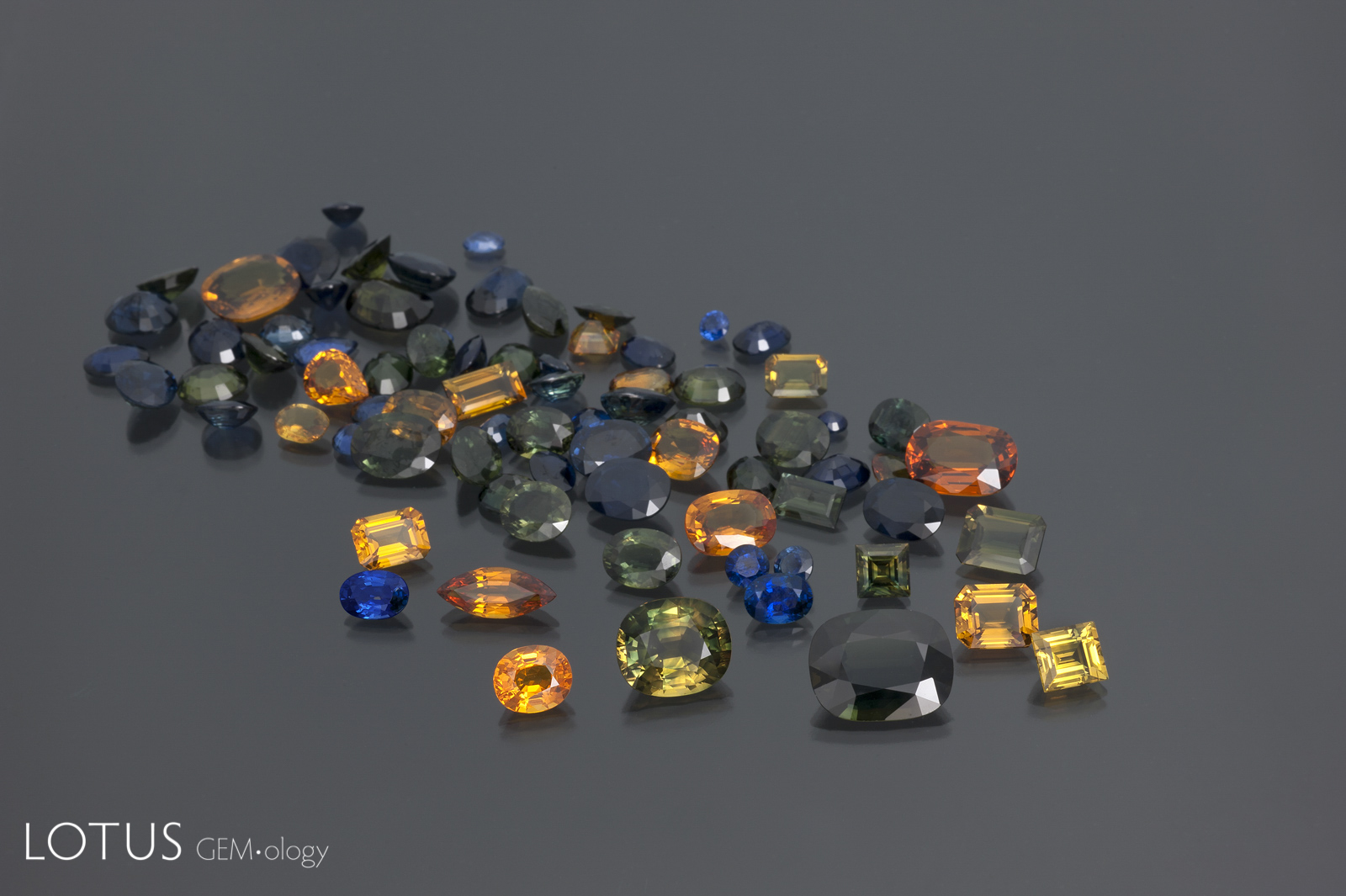

There are a number of sapphire sources around the world where sapphire is found associated with alkali basalts. These include Australia, Cambodia, Cameroon, China, Ethiopia, Laos, Madagascar (far north), Nigeria, Rwanda, Thailand and Vietnam. In such stones, the sapphires formed within the earth, but were brought to the surface by volcanic eruptions. During these volcanic events, the already-formed crystals underwent a natural heating process. The result is that basalt-related sapphires often show features associated with sapphires that have undergone artificial heat treatment. Due to this fact, it is often impossible for labs to know if a basalt-related stone has been artificially heat treated.

The vast majority of basalt-related sapphires occur in blue, green and yellow (BGY) colors. Stones tend to have much higher iron contents when compared with fine blue sapphires from Kashmir, Burma, Sri Lanka, Madagascar and Tanzania. But again, overlap is possible. Most major labs today will refuse to issue country of origin reports on basalt-related sapphires, declaring the origin to be "basalt related." This is because the various sources show so much overlap in their features.

Among basaltic sapphire deposits, Australia once reigned supreme, but production today is a tiny fraction of what it was in the 1970s. Thailand's production is way down, the Cambodian mines at Pailin are finished and China's once-large production of very dark sapphire at Shandong is also now zero. In the current market, basalt sapphire comes mainly from Nigeria/Cameroon, Ethiopia and the far north of Madagascar.

Sapphire from Bang Kha Cha/Khao Ploi Waen, near Chanthaburi, Thailand. This shows the typical blue-green-yellow (BGY) color range of basalt-related sapphire. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul/Lotus Gemology; specimens: World Sapphire; click on a photo for a larger image

Sapphire from Bang Kha Cha/Khao Ploi Waen, near Chanthaburi, Thailand. This shows the typical blue-green-yellow (BGY) color range of basalt-related sapphire. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul/Lotus Gemology; specimens: World Sapphire; click on a photo for a larger image

Montana sapphire

While not really of consequence in the world sapphire market, there is strong demand for Montana sapphire in the US. It comes in two distinctive flavors, Yogo and non-Yogo (meaning Rock Creek/Gem Mountain, Missouri River and Dry Cottonwood Creek).

Yogo sapphires have been mined on and off since the late 19th century. With beautiful blue to lilac colors, high clarity and no color zoning, the only thing that has stopped them from being world class is the size. Most crystals are flat and it is a rare stone that can cut a one-carat piece. Two-carat stones are extraordinarily rare. Yogo sapphires fetch prices in the US far above what would be paid in the rest of the world.

Stones from the other Montana mines come in fancy colors and blues tend to be a bit grayish. Rock Creek/Gem Mountain produces prodigious quantities, but virtually all require heat treatment.

Age dating of sapphire

It should now be clear that labs have tremendous difficulty in separating fine sapphires from Kashmir, Burma, Sri Lanka, Madagascar and Tanzania. Indeed, such origin separations are probably the most challenging in the fine sapphire market. Not only have inclusion studies reached a brick wall, but advanced chemical fingerprinting has also not provided clear separation.

But there are significant differences in age. The Sri Lanka, Madagascar and Tanzania deposits formed some 750–450 million years ago as a result of the Pan-African orogeny, while the Kashmir and Burma deposits were created by the Himalayan orogeny about 45–5 million years ago. If one could age date sapphire, then it would be possible to clearly separate these two groups of sources from one another. Attempts at age-dating zircon crystals in sapphire have shown some promise, but this requires such crystals to be not just present, but also at or near the surface. In most sapphires, this is not the case. But if a way of age dating sapphire becomes possible, a bit more accuracy in determining the origin of sapphire might be possible.

For the curious, the volcanic eruptions that brought basalt-related sapphires to the surface formed 16–2 million years ago, but age dating of their zircon inclusions suggests that the sapphires could have formed even earlier in some cases (Giuliani et al., 2014)

China • Enter the Dragon

Probably the biggest change that has come to the world sapphire market has had nothing to do with the supply side, but instead is related to the re-emergence of China as a world economic powerhouse. Those who do not travel or who get their news mainly from US-based sources may be unaware, but what has happened in China over the past three decades is nothing short of astonishing. China's economy is poised to surpass the US as the world's largest as early as 2020. But putting numbers aside, China has undergone many other changes.

Those raised on Pearl Buck's The Good Earth will be shocked to see many parts of modern China. With over a billion internet users, the country today is virtually a cashless society, where even small payments to street vendors are handled electronically. This is an end run around the US-dominated banking/credit card system and signals the possible beginning of the end of the US dollar as the world's reserve currency. The latter is hugely important, as the dollar as the reserve currency allows the US to print money out of thin air and support ever-rising deficits.

But unlike diamond, a reserve currency is not forever. It was once the Byzantine solidus, later the Venetian ducat and much later, the British pound (Black, 2014). In each case, those were dropped as the currency was debased from within, causing investors to lose confidence.

A customer uses her cell phone to pay for a drink from a street vendor at the Shifosizhen jade market in China's Henan province. China today is virtually a cashless society. Photo: Richard W. Hughes, November 2019; click on a photo for a larger image

A customer uses her cell phone to pay for a drink from a street vendor at the Shifosizhen jade market in China's Henan province. China today is virtually a cashless society. Photo: Richard W. Hughes, November 2019; click on a photo for a larger image

China also leads the way in 5G technology and, most importantly, was the first to market with quantum encryption, which destroys a signal if any form of tampering or modification is detected. This deeply undercuts the US National Security Agency's ability to spy on communications and possibly explains the real reason why Huawei's CFO was arrested in Canada in 2018. In what can only be called a stroke of geopolitical genius, China has also made the quantum encryption code "open source" (Goldman, 2019), allowing the world to adopt the technology and modify it for free.

While US infrastructure is crumbling, China has invested in its own nation, building a vast network of new roads, high-speed trains and airports. Alibaba's CEO Jack Ma summed it up best when he said the U.S. has wasted over $14 trillion in fighting wars over the past 30 years, rather than investing in infrastructure at home (Yarrow, 2017).

But we are writing about sapphire, not global geopolitics. How has the rise of China affected the sapphire trade? First, in buying. Today in Thailand, Chinese buyers outnumber US buyers by at least 10:1. What this means for the US is higher prices and fewer stones coming their way. But there are other factors, as discussed in Chapter 6 of our Ruby & Sapphire: A Gemologist's Guide:

With the Communist revolution in 1948, China turned inward, cutting off the economy of the planet's most populous nation from the rest of the world.

Following the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, that began to change. By the 1990s, when Chinese gem buyers reappeared in quantity on the world gem stage, the entire gem treatment era had passed them by. They effectively reentered the market with pre-1949 ideas about gems. And one of those ideas was that natural gems should be entirely natural. A decade later, when the world economic crisis hit in 2008, Chinese buyers were dominant. Because they were relatively inexperienced, for protection they demanded that lab reports accompany virtually every gem they purchased.

And when some lab reports showed that what they were being told was completely natural was anything but, they rejected the stones, demanding completely untreated gems. The result was not just a rise in the demand for skilled lab services, but also an unprecedented increase in the price of natural gems. Suddenly stones that previously would have been treated, were more valuable when kept in their pristine natural state. It was a revolution.

"Disclosure: A Revolution Rebottles the Treatment Genie"

Richard Hughes, Wimon Manorotkul & E. Billie Hughes

Ruby & Sapphire: A Gemologist's Guide, 2017, p. 240

China has also made huge investments in education and this spills over into the gemological world. Today China has more university level gemology programs than the rest of the world combined. If this trend continues, it is entirely possible that a half a century from now, a working knowledge of Chinese may be integral to keep up with the latest in gemological developments.

One final note about how China is transforming the ideas of trade. While most nations have television home shopping networks that involve such exorbitant costs that sales are measured in dollars per minute of airtime, dealers in China have created an entirely new paradigm of gem trading. Visit any major gem market in China (and there are hundreds that dwarf anything in the rest of the world) and you will see independent traders using their cell phones and the internet to create tens of thousands of mini home shopping networks, any of which can be followed by customers. Like a modern remix of Chinese opera, hosts joust with vendors for the "best" deal for their customers. The glue that holds the drama together is a vast network of guaranteed next-day delivery to virtually any point in China via a cargo jet fleet twice as large as FedEx, along with the option for customers to return any purchase within a few days if they are not happy with what they receive. This is certainly not your grandparents' "communist" China.

All that Chinese need to start their own home shopping network is a cell phone, an internet connection, a good personality and hard work. Despite the myth of China in the West as a monolithic communist society, today the country is a hotbed of individual entrepreneurship. Photo: Richard W. Hughes, Guangdong province, China, 2018; click on a photo for a larger image

All that Chinese need to start their own home shopping network is a cell phone, an internet connection, a good personality and hard work. Despite the myth of China in the West as a monolithic communist society, today the country is a hotbed of individual entrepreneurship. Photo: Richard W. Hughes, Guangdong province, China, 2018; click on a photo for a larger image

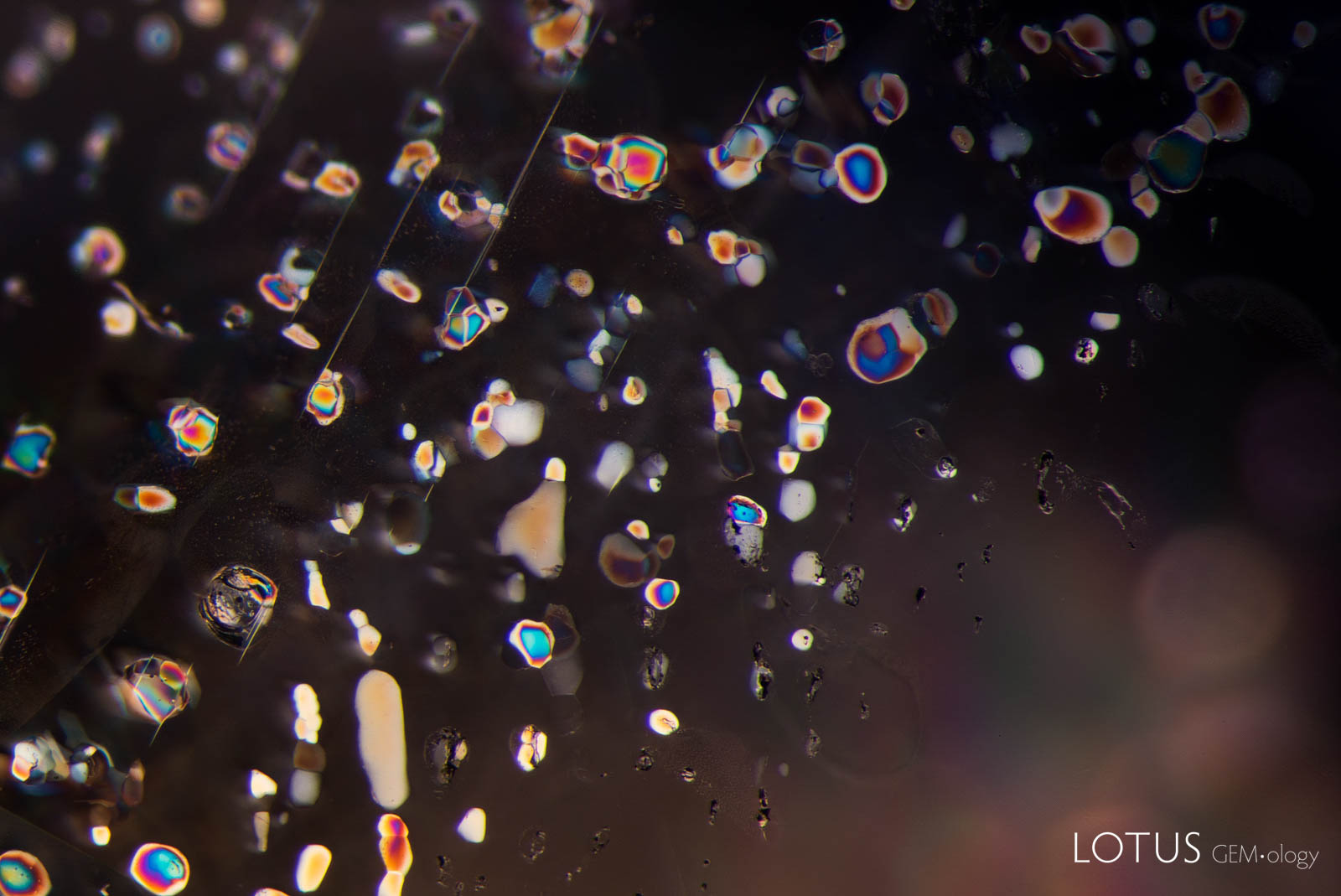

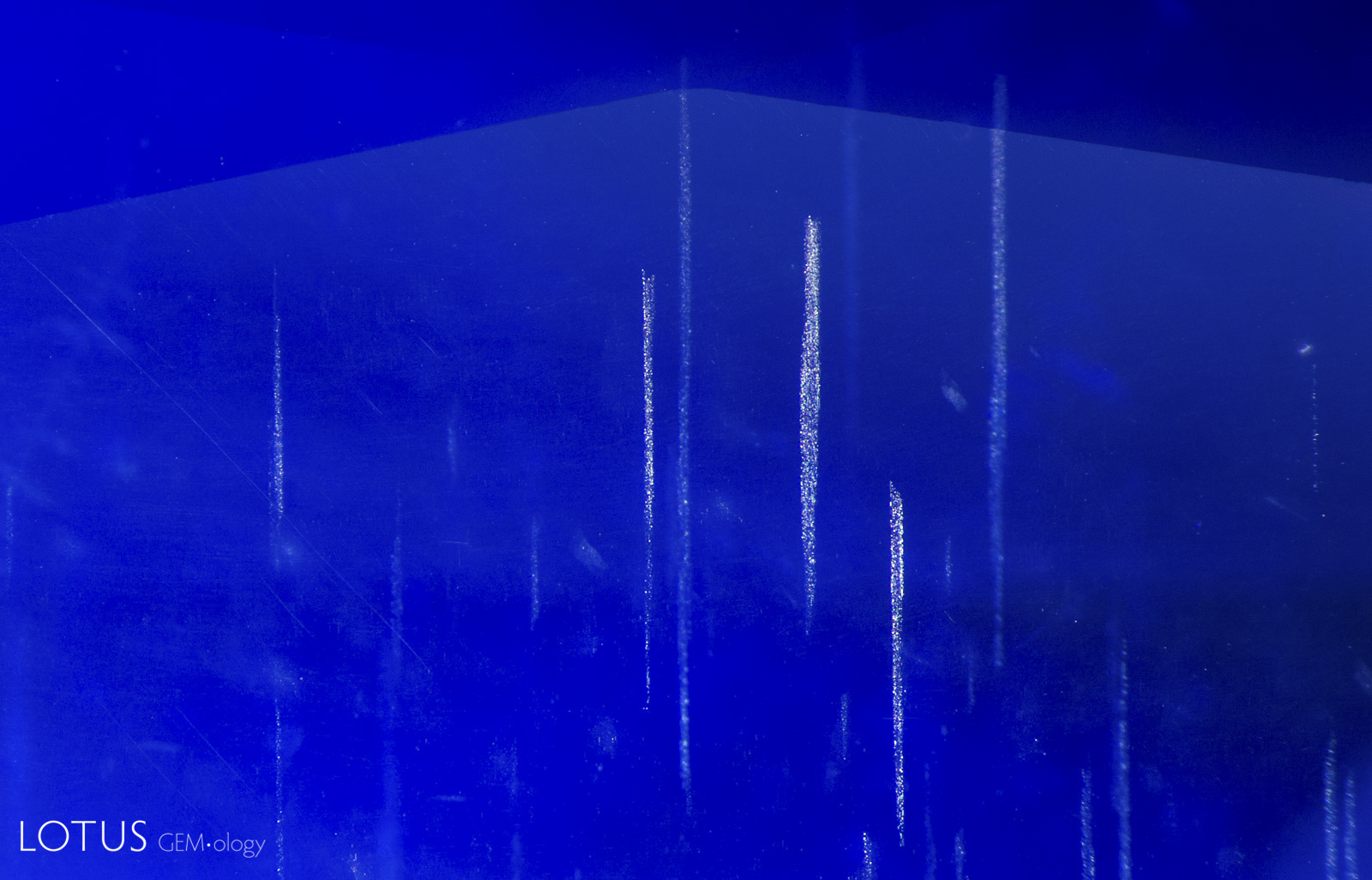

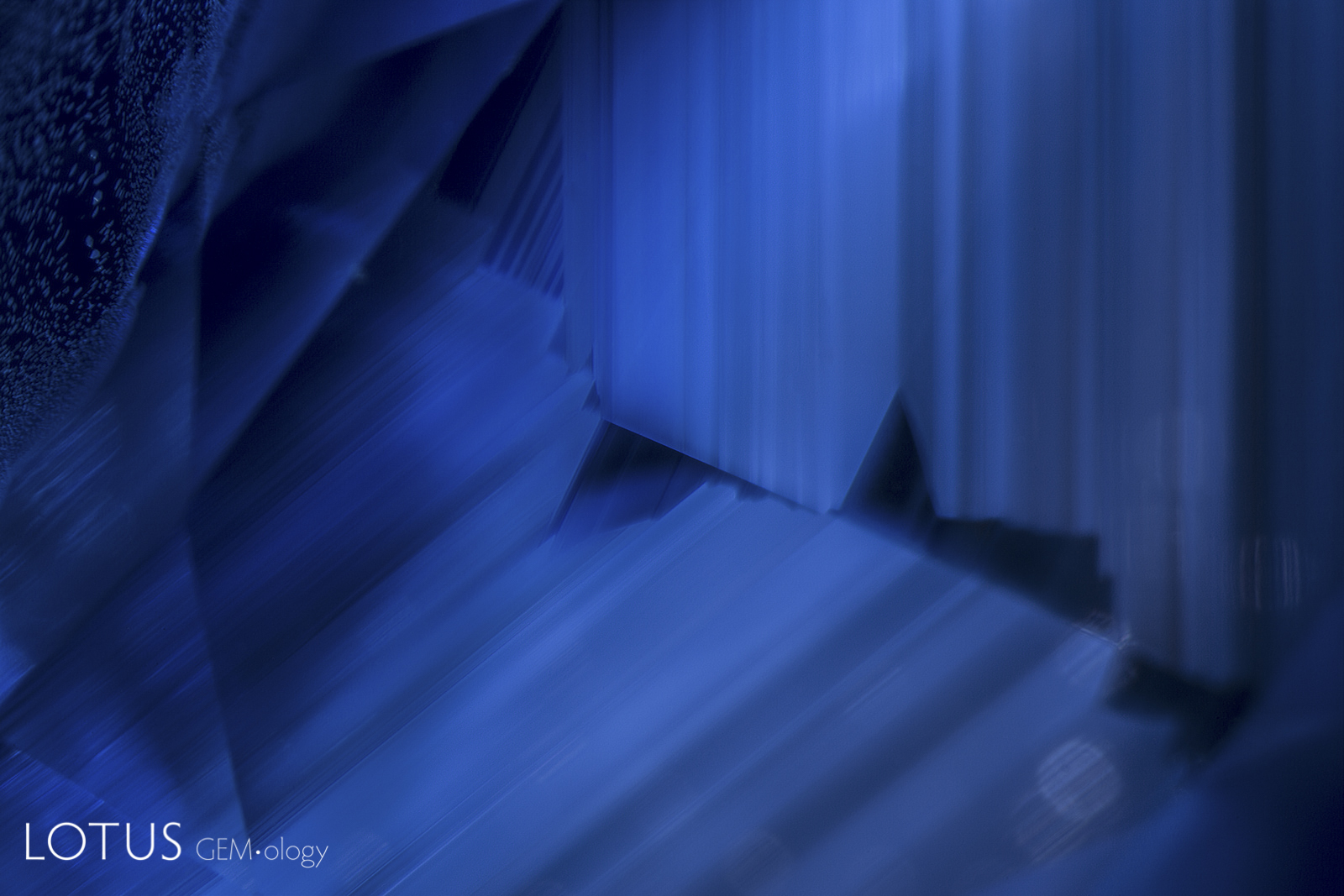

A note on treatments

Virtually all readers are aware that many sapphires are heat treated to improve their value. This ranges from relatively low-temperature (800–1200°C) treatments on basalt-derived sapphires to lighten their color, through high-temperature (1400–1800°C) treatments on low-iron metamorphic sapphires to dissolve rutile silk and produce a blue color (geuda sapphire), to extremely high-temperature (1700–1900°C) treatments to diffuse titanium or beryllium into the stones to alter their color. A further recent development is the high-temperature heating of sapphire under pressure (HT+P) (Various labs, 2019).

In the market, the highest prices are paid for sapphires that are completely untreated. Over the past decade, the demand and price for these stones has greatly appreciated. The higher the quality and larger the size, the greater the price gap between natural and heated. For example, on a one-carat stone, the premium might be 100%, but that could grow to 500% or more on a ten-carat stone.

In addition to heat treatment, common treatments seen in corundum including fissure filling with colorless oil or, more rarely, with colored oils/dyes. Oiling is a particular problem with Burmese sapphire but can be found in any sapphire with the requisite fissures. Rarely seen treatments include surface coatings.

Glass-filled sapphires using a high refractive index glass, sometimes doped with cobalt, are also commonly seen at the extreme low end of the market. And then there are synthetics, imitations and assembled stones to watch out for.

With padparadscha sapphires, irradiation treatments are on the rise again. Thus any stone in this color range requires a fade test to make sure the color is stable.

Treatments are like vampires—they come back from the dead to bite you. In the early 1980s, Sri Lankan pink sapphires were sometimes irradiated to create padparadscha-like colors. The resulting color was unstable, and would fade within an hour if the stone was placed within a centimeter of a 150-watt incandescent spotlight. When labs starting doing such fade tests, the irradiated stones quickly disappeared. However, as the above shows, they are back. The photos show a stone sent to Lotus Gemology for testing, before (left) and after (right) a 1-hour fade test. Photos: Sora-at Manorotkul/Lotus Gemology.

Treatments are like vampires—they come back from the dead to bite you. In the early 1980s, Sri Lankan pink sapphires were sometimes irradiated to create padparadscha-like colors. The resulting color was unstable, and would fade within an hour if the stone was placed within a centimeter of a 150-watt incandescent spotlight. When labs starting doing such fade tests, the irradiated stones quickly disappeared. However, as the above shows, they are back. The photos show a stone sent to Lotus Gemology for testing, before (left) and after (right) a 1-hour fade test. Photos: Sora-at Manorotkul/Lotus Gemology.

Final thoughts

It is beyond the scope of this article to fully describe how to separate sapphires of different origins and/or how to separate untreated from treated gems. That would require an entire book. Fortunately we have written it, the aforementioned Ruby & Sapphire: A Gemologist's Guide. It is an essential text to explore the subject further.

Because of the high technology that has been brought to bear on treating stones, and because origin determination is so problematic, the days of an average gemologist/appraiser making such decisions are long gone. We must get used to the idea that anything of consequence today requires testing in a major lab.

References

- Black, S. (2014) These guys used to issue the world’s reserve currency too. Sovereign Man, 13 Aug. <https://www.sovereignman.com/trends/these-guys-used-to-issue-the-worlds-reserve-currency-too-14845/>, accessed 7 Dec. 2019.

- Giuliani, G., Ohnenstetter, D., Fallick, A.E., Groat, L. and Fagan, A.J. (2014) The geology and genesis of gem corundum deposits. In Geology of Gem Deposits, Groat, L.A., ed., 2nd ed., Quebec, Canada, Mineralogical Association of Canada, Short Course Series, Vol. 44, pp. 29–112.

- Goldman, D.P. (a.k.a 'Spengler') (2019) US-China tech war and the US intelligence community. Asia Times, 4 Nov. <https://www.asiatimes.com/2019/07/article/us-china-tech-war-and-the-us-intelligence-community/>, accessed 7 Dec. 2019.

- Hughes, R.W. (1990) A question of origin. Gemological Digest, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 16–32.

- Hughes, R.W., Manorotkul, W. & Hughes, E.B. (2017) Ruby & Sapphire: A Gemologist's Guide. Lotus Publishing, Bangkok, 816 pp.

- Hughes, R.W. and Zajicek, R. (1997) Catfights—Enhancement Codes and Trade Wars. ICA Gazette, June, pp. 7–9; RWHL.

- Link, K. (2015) Age determination of zircon inclusions in faceted sapphires. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 34, No. 8, October, pp. 692–700; RWHL.

- [various labs] (2019) Squeezing sapphire: Pressure-heated sapphire.

- Yarrow, J. (2017) Chinese billionaire Jack Ma says the US wasted trillions on warfare instead of investing in infrastructure. CNBC, 18 Jan. <https://www.cnbc.com/2017/01/18/chinese-billionaire-jack-ma-says-the-us-wasted-trillions-on-warfare-instead-of-investing-in-infrastructure.html>, accessed 10 Dec. 2019.

About the authors

Richard W. Hughes is one of the world’s foremost experts on ruby and sapphire. The author of several books and over 170 articles, his writings and photographs have appeared in a diverse range of publications, and he has received numerous industry awards. Co-winner of the 2004 Edward J. Gübelin Most Valuable Article Award from Gems & Gemology magazine, the following year he was awarded a Richard T. Liddicoat Journalism Award from the American Gem Society. In 2010, he received the Antonio C. Bonanno Award for Excellence in Gemology from the Accredited Gemologists Association. The Association Française de Gemmologie (AFG) in 2013 named Richard as one of the Fifty most important figures that have shaped the history of gems since antiquity. In 2016, Richard was awarded a visiting professorship at Shanghai's Tongji University. 2017 saw the publication of Richard and his wife and daughter's Ruby & Sapphire • A Gemologist's Guide, arguably the most complete book ever published on a single gem species and the culmination of nearly four decades of work in gemology. In 2018, Richard was named Photographer of the Year by the Gem-A, recognizing his photo of a jade-trading market in China, while in 2020, he was elected to the board of directors of the Accredited Gemologists Association and was appointed to the editorial review board of Gems & Gemology and The Australian Gemmologist magazine. Richard's latest book, Jade • A Gemologist's Guide, was published in 2022.

E. Billie Hughes visited her first gem mine (in Thailand) at age two and by age four had visited three major sapphire localities in Montana. A 2011 graduate of UCLA, she qualified as a Fellow of the Gemmological Association of Great Britain (FGA) in 2013. An award winning photographer and photomicrographer, she has won prizes in the Nikon Small World and Gem-A competitions, among others. Her writing and images have been featured in books, magazines, and online by Forbes, Vogue, National Geographic, and more. In 2019 the Accredited Gemologists Association awarded her their Gemological Research Grant. Billie is a sought-after lecturer and has spoken around the world to groups including Cartier and Van Cleef & Arpels. In 2020 Van Cleef & Arpels’ L’École School of Jewellery Arts staged exhibitions of her photomicrographs in Paris and Hong Kong.

Notes

First published in the GemGuide, January/February 2020, Vol. 39, No. 1, pp. 4–10.