A discussion of rutile silk in corundum and its use in detecting artificial heat treatment. Careful examination of these "silk" inclusions can provide vital clues to unmask heated gems.

If I'd only seen through the silky veils of ardor…. Joni Mitchell

What follows is a love story. We admit it. Our heart is on our sleeves. We are smitten, head-over-heels in love with the exotic and beguiling internal lattice that gemologists call "silk."

How do we love thee? Let us count the ways. You are the one that lets some of our rubies and sapphires sparkle like the night sky, your asterism such a wonder of nature. Not to mention your beauty as you wink up at us when the light is just so. And finally, you are our guardian, our coalmine canary, a tiny thermometer in our gems, willing to sacrifice your own life to let us know when Man’s ego has grown so large that he thinks he can play God. For this alone, we sing your praises.

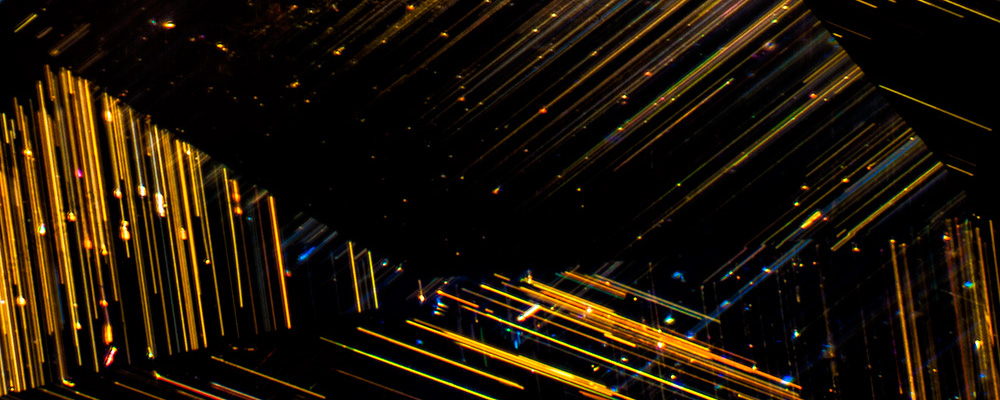

Figure 1. A secret silken world. Daggers of rutile lance their way through the interior of this untreated Mogok sapphire. The presence of such perfectly formed rutile needles are proof that this sapphire has not been heated to a high temperature. Photo: John I. Koivula/microWorld of Gems

Figure 1. A secret silken world. Daggers of rutile lance their way through the interior of this untreated Mogok sapphire. The presence of such perfectly formed rutile needles are proof that this sapphire has not been heated to a high temperature. Photo: John I. Koivula/microWorld of Gems

Just what is this inclusion we call silk? It is actually composed of tiny crystals formed through a process called exsolution, the "unmixing" of a solid solution. At high temperatures, crystals have more defects and a more-expanded lattice, and thus are better able to absorb impurities. As the crystal cools, defects are reduced. This may force impurities to crystallize out. But because of the constraints placed on their movement by the solid host, impurity atoms are unable to travel large distances. Therefore, rather than forming large crystals, they migrate short distances to form multitudes of tiny needles, plates and particles, along the directions in the host where space permits.

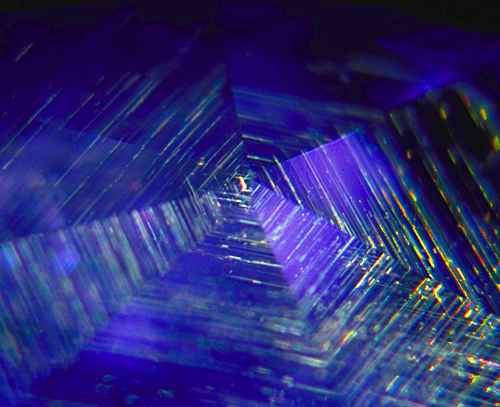

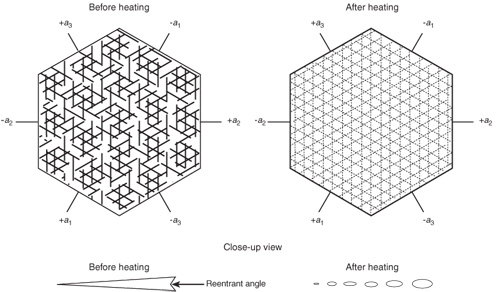

Figure 2. Exaggerated and simplified atomic view of exsolution in corundum. During exsolution, solute atoms migrate together to form their own crystals within the host. The orientation of these crystals is governed by the host structure. As a result, they are exsolved in a specific pattern. Within corundum, rutile (TiO2) unmixes in the basal plane, parallel to the faces of the second-order hexagonal prism {1120}. Illustration: Richard W. Hughes

Figure 2. Exaggerated and simplified atomic view of exsolution in corundum. During exsolution, solute atoms migrate together to form their own crystals within the host. The orientation of these crystals is governed by the host structure. As a result, they are exsolved in a specific pattern. Within corundum, rutile (TiO2) unmixes in the basal plane, parallel to the faces of the second-order hexagonal prism {1120}. Illustration: Richard W. Hughes

One of the keys to recognizing exsolved inclusions is that they always form in a specific pattern within the host. That pattern may be different for differnt minerals crystallizing within the same host material (for example, rutile is exsolved in corundum in three directions crossing at 60/120° in the basal plane). Virtually all tiny, oriented needle, particle and platelike inclusions found in minerals are formed via exsolution. These inclusions give rise to asterism and cat's eye phenomena. The best manifestation of this is the concentrations of rutile and hematite-ilmenite silk and needles in corundum.

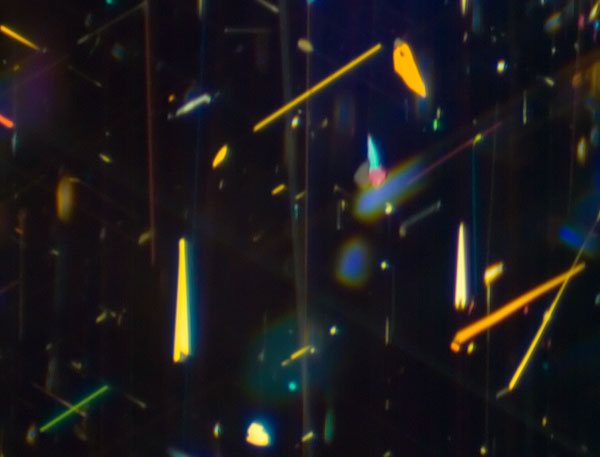

Figure 3. Gossamer…

Figure 3. Gossamer…

A rutile silk spider’s web spun beneath the facets of an untreated Sri Lankan sapphire. Photo: Richard W. Hughes, Lotus Gemology.

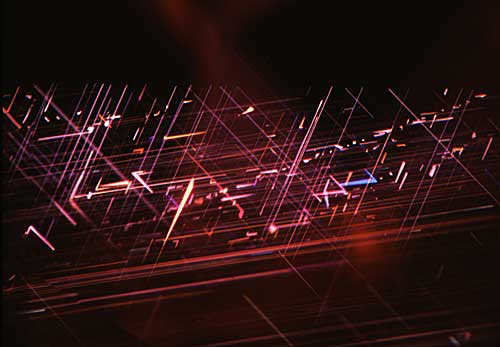

Among the most diagnostic features of corundum is the white clouds of exsolved rutile (TiO2). According to Edward Gübelin, Gustav von Tschermak was the first to identify rutile in corundum in 1878. Such clouds vary from dense concentrations, which follow, and distort, the crystals’ color zoning, to thinly-woven tapestries. At times, only slender threads or particles are visible, while in other cases knife or dart shapes appear (see Figure 1). Closer examination reveals many of these to be twin crystals with tiny v-shaped re-entrant angles visible at the broad end. They are flattened so thin in the basal plane that, when illuminated with a fiber-optic light guide from above, bursts of iridescent colors are seen, due to the interference of light from these microscopically-thin mineral lances.

The needle clouds just described are termed silk, in analogy to their threadlike pattern and are responsible for the asterism, or star effect. Not only rutile may form silk in corundum; hematite (Fe2O3), ilmenite (FeTiO3) or hematite-ilmenite mixtures have been reported. Rutile in corundum tends to unmix parallel to the faces of the second-order hexagonal prism {1120}, intersecting in three directions at 60/120° in the basal plane. Hematite-ilmenite exsolves in the basal plane parallel to the first-order hexagonal prism {1010}. Thus when both rutile and hematite-ilmenite are present in the same crystal, a 12-rayed star is possible.

Figure 4. Effects of high-temperature heat treatment on rutile silk in corundum.

Figure 4. Effects of high-temperature heat treatment on rutile silk in corundum.

Left: In corundum, rutile exsolves in three directions in the basal plane, parallel to the faces of the second-order hexagonal prism {1120}. Before heating, rutile silk consists of needles which, when highly magnified, are often tiny arrow- or dart-shaped twins with small reentrant angles at the wide end. The rutile needles are extremely thin in cross-section and are generally flattened in the basal plane. Overhead fiber-optic illumination with the microscope will reveal such details.

Right: High-temperature heat treatment causes rutile to be partially dissolved into the corundum, but traces often remain behind, visible with fiber-optic lighting. Each needle, rather than coalescing into one globule, instead dissolves into a series of tiny droplets arranged in the same pattern as before heating. This partially-dissolved silk may be indicative of heat treatment. However, minute exsolved particles, which can occur naturally, may be confused with the partially-dissolved silk of heated gems. The presence of long needles and dart- and arrow-shaped rutile is a strong indication that the gem has not undergone high-temperature heat treatment. Illustration: Richard W. Hughes

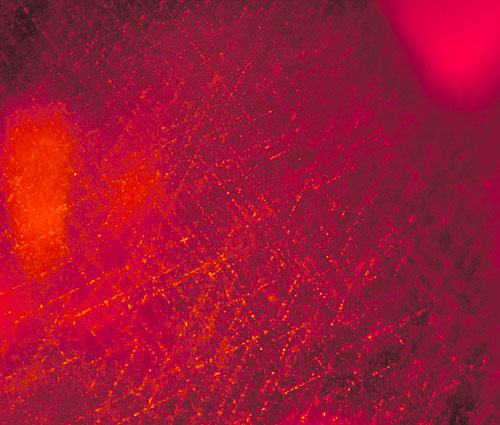

Figure 5. Canary in a cinnebar mine

Figure 5. Canary in a cinnebar mine

When a ruby or sapphire is heat treated at a high temperature, rutile silk is partially resorbed into the crystal, thus clarifying it. But rutile is rarely completely pure. The more impurities present, the more visible the silk "skeletons" following treatment, as shown above. Thus rutile acts as an internal thermometer in the gem, letting us know when Man is trying to play God. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Figure 6. Arrows of love

Figure 6. Arrows of love

Dart-shaped silken arrows of love. Can anyone not be smitten with such stunning displays? Untreated Sri Lankan ruby. Photo: John I. Koivula/microWorld of Gems

If I'd only seen through the silky veils of ardor…

What a killing crime this love can be… Joni Mitchell

Some shirk battle, afraid of missiles sent their way. Not us. Like Tibetans rounding Mount Kailash, we will gladly prove our devotion on our hands and knees. We are willing pilgrims along the Silk Road. We fear no slings; we relish these god-sent daggers. Let them penetrate our hearts, infect our souls.

What is love? We have gazed at and through the silky veils of ardor. And having journeyed to the other side, we wish for nothing less than to die a sweet slow silken death. We promised you a love story. Oh what a killing crime this love can be…

|

Secrets in Sapphire: Mystery Inclusions in Rutile Silk From the beginning of my gemological studies in 1979, I have been intrigued by inclusions and none have provided greater fascination than rutile silk. I never tire of gazing at these gossamer-like strands in untreated ruby and sapphire. Initially, I was attracted to the brilliant colors; later, I learned to appreciate their structural details, noting that what I first regarded as single crystals were actually microscopic twins with tiny re-entrant angles at the broad ends. Over the past few years, I've noticed a further hidden detail. Virtually all exsolved rutile needles large enough to be clearly resolved with my microscope (up to 70x magnification) show tiny daughter crystals at the broad end, implanted directly in the re-entrants. What are these hidden mysteries? Mostly likely, they are impurity phases forced out of solution with the rutile, probably something like hematite (trigonal Fe2O3) or ilmenite (trigonal FeTiO3). I am in search of a specimen where these daughter crystals are both large enough and close enough to the surface for analysis. – Richard W. Hughes

|

About the Authors

John I. Koivula, B.A., B.Sc., G.G., F.G.A., Fellow Royal Microscopical Society is the co-author of the magnificent Photoatlas of Inclusions in Gemstones, Vols. 1–3 and the author of the MicroWorld of Diamonds, along with several other books and numerous articles. He is currently Analytical Microscopist at the Gemological Institute of America and is the world's foremost gem photomicrographer and inclusionist. John’s images have graced the covers and contents of numerous books and journals. In addition, he won 1st Place and others in Nikon’s Small World photomicrographic competitions. Koivula is an honorary life member of both the Finnish Gemmological Society and the Gemmological Association of Great Britain, and was named as one of the 64 most influential people of the 20th century in the jewelry industry by Jewelers' Circular Keystone magazine and one of the 50 most important figures that have shaped the history of gems since antiquity by the Association Française de Gemmologie (AFG). John was bestowed The Richard T. Liddicoat Award from GIA in 2009. He also has been awarded the Robert M. Shipley Award by the American Gem Society, the Scholarship Foundation Award by the American Federation and California Federation of Mineralogical Societies, the Antonio C. Bonanno Award for excellence in gemology by the Accredited Gemologists Association, and Koivula was the first recipient of the Richard T. Liddicoat Journalism Award from the American Gem Society. John was also the technical and scientific advisor to the famous MacGyver television series from 1986–1993. Many of his books can be seen at www.microworldofgems.com, and are available from the GIA and Gem-A bookstores.

Richard W. Hughes is one of the world’s foremost experts on ruby and sapphire. The author of many books and over 170 articles, his writings and photographs have appeared in a diverse range of publications, and he has received numerous industry awards. Co-winner of the 2004 Edward J. Gübelin Most Valuable Article Award from Gems & Gemology magazine, the following year he was awarded a Richard T. Liddicoat Journalism Award from the American Gem Society. In 2010, he received the Antonio C. Bonanno Award for Excellence in Gemology from the Accredited Gemologists Association. The Association Française de Gemmologie (AFG) in 2013 named Richard as one of the Fifty most important figures that have shaped the history of gems since antiquity. In 2016, Richard was awarded a visiting professorship at Shanghai's Tongji University. 2017 saw the publication of Richard and his wife and daughter's Ruby & Sapphire • A Gemologist's Guide, arguably the most complete book ever published on a single gem species and the culmination of four decades of work in gemology. In 2018, Richard was named Photographer of the Year by the Gem-A, recognizing his photo of a jade-trading market in China, while in 2020, he was elected to the board of directors of the Accredited Gemologists Association and was appointed to the editorial review board of Gems & Gemology and The Australian Gemmologist magazine. In 2022, Richard published Jade • A Gemologist's Guide, while 2024 brought Broken Bangle • The Blunder-Besmirched History of Jade Nomenclature. His jade trilogy was completed in 2025 with his translation of Heinrich Fischer's Nephrite and Jadeite.

Notes

First published in May 2005, while John and I were at the AGTA GTC. Working with John was one of the greatest pleasures of my life, sadly far too brief. Looking back, I can only wonder what might have been…