An essay on buying gems at the source in Asia, with a discussion of how con men play on the greed of those who believe gems will be cheaper at the mines.

There are many humorous things in the world; among them the white man's notion that he is less savage than the other savages. Mark Twain, Following the Equator, p. 213

Go East young man

From the times of Alexander and before, the East has been considered the major repository of gems and Europeans traveling to the Orient quickly come in contact with precious stones. Of sorts.

Like Tavernier, my career in gems began with a journey from Europe to Asia. Having been offered various and sundry "jewels and priceless relics" from all points east of Istanbul, my friend and I decided to take the plunge in Jaipur. Throwing caution to the wind, we would purchase a small parcel of Indian star rubies for resale. Our search began in a small jewelry shop near Jaipur's Hawa Mahal (Hall of Winds).

Clever chaps that we were, Peter and I concluded we needed a good ruse. Deep in the core of our being, we just knew that the vulpine Oriental venders would hold back the finest goods. Thus we demanded the seller "bring out the good stuff" after each parcel was displayed. Peter, playing the best Abbott to my Costello, would pass a packet across the table for my look-see. Upon poring over a single $1/ct ruby for ten minutes, holding both stone and loupe at arm's length, and checking the star from all directions, I then pronounced judgment: "My good man, this will just not do! We are big dealers, with no time to waste! Show us the good stuff!"

Not even a single paise descended from heaven. Instead, following several parcels and rejections, the seller looked us straight in the eye and, in the vernacular, told us we were full of that which emanates from the rear of a Hindu holy animal. He then proceeded to scold us, explaining that, from the moment we stepped into his shop, it was obvious we were simple tourists, not dealers. Such was apparent merely by the way we handled the loupe and stone papers, not to mention the fact that I had failed to notice the star on one stone because it was upside down. We beat a hasty retreat and, regrouping outside, decided our hiking boots must have given us away.

This was my introduction to the gem business. The year was 1976; I had just brushed past 19.

Long con

In 1978, on my second visit East, a friend and I found ourselves touring Bangkok's Grand Palace. While admiring the superb handiwork of Thai craftsmen, we were approached by a well-dressed man who spoke excellent English. He was a teacher on his day off and offered to show us around the palace grounds. Following a wonderful tour, my friend and I mentioned we'd like to tour Bangkok's famous klongs. No problem, he'd help arrange it. Some three hours later, after having visited both Grand Palace and klongs, and having acted the perfect guide, he casually rolled out the come-on. Today was a special day, where Thailand's government generously allowed foreigners to purchase gems duty free. If we had a bit of time, he knew a shop where we could get a steal.

We were impressed. My sweet lord, where else would a teacher agree to spend hours showing us around without pay, and with a smile, to boot! It was only the fact that my friend and I had another appointment that stopped us from becoming instant millionaires.

Selling short

Ignorance was certainly bliss. Unaware of what might have befallen me, I later hailed a taxi in front of my humble hotel to take me to an embassy for a visa (a distant and expensive ride in Bangkok's then traffic-choked streets). The cabbie had a different proposition. If I would agree to spend the morning visiting shops, he'd give me a free ride to the embassy and more. Here's how it worked:

For every jewelry store I visited, he'd be paid 100 baht, whether I bought or not. All I needed was to go in, pretend interest, sip a Coke, look at various and sundry rings, pendants, etc., sip a Coke, then leave.

Several hours later he spit me out in front of my hotel, my back teeth floating from all the Cokes I had drunk. Completely put me off that beverage for months. But it was worth it. Along with the free taxi, I was several hundred baht richer.

Years later, when I was managing the Asian Institute of Gemological Sciences in Bangkok, I would watch the freshly shorn marks walk in our front door. Not unlike my hiking boots in Jaipur, their world traveler outfits instantly gave them away. As they opened their mouths to speak, I gently interjected: "Don't tell me, you were at the [Grand Palace/Floating Market/Malaysia Hotel] and you met a [teacher/policeman/student/businessman/housewife] on their day off and they told you today was a [holiday/special day/tax-free day]." After dusting off their tongues and rolling them back into place, I explained how the scam operated, letting them know they were not alone. It was unpleasant work, but someone had to do it.

The scam works like this:

Camera huggers are approached outside hotels or at tourist spots. Catchers invariably pose as teachers, students, police or others of respectable occupation on their day off. After showing the marks around a bit, the line is played out, with various ruses used to convince marks that what the catchers say is true. This can include letters of recommendation, other "innocent" Thais explaining what a good deal it is, even other foreigners in on the game. The grifters' happy ending is when tourists part with beaucoup coin in return for overpriced gems. Because gems are not something with a fixed price, many scam artists don't even bother with selling synthetics or glass. All that is needed to do the deal is for the mark to buy low quality natural gems at an inflated price.

|

Taxi Driver Now it is not good for the Christian's health to hustle the Aryan brown, – Solo from Li'bretto of Naulahka Living in Bangkok, one quickly becomes inured to the tourist scams, shams and various rip-offs. But one I'll never forget is the day I stepped into a taxi on my way to work. Now understand that a Bangkok taxi ride provides much fuel for thought, conversation and otherwise, since, due to traffic, most time is spent going absolutely nowhere. One particular morn, as I sat contemplating the possibility of life elsewhere on the planet, the driver leaned back and handed me a stone paper. "Excuse me, but my last passenger dropped this. Do you know what it is?" Obviously he did not realize he was speaking to one of the world's preeminent gemologists. Raising loupe to eye, the gems were quickly identified as Verneuil synthetics. Arriving at my destination, I stepped out, informing him that the pieces were synthetic, of little value, and that he should discard them. Several days later, in another idling cab, I was asked to evaluate yet another parcel of synthetic sapphires, left behind by yet another passenger. Who? You talking to me? Seems they all had holes for pockets. Only later, upon reflection in my morning coffee (and with a discreet whisper from my future wife), did the coin finally drop. Guess I'm a slow learner. – Richard W. Hughes, 1997, Ruby & Sapphire |

To the mines!

All of us who venture East suffer from the same delusions, principally that we are a rare breed, among the first since Marco Polo to make the journey. And this delusion is the sharp point of the hook, because delusions are what the grifter counts on. Without delusions (and a healthy dollop of greed), there is no sale.

But rest assured, the Bangkok gem scam is not a recent invention. Way back in 1934, J.F. Halford-Watkins wrote of gem trading in Chanthaburi (Thailand):

In the early days there was a sect of wild country workers known as Kamin who, when they wished to sell their sapphires, would not let a prospective purchaser examine them, but would place the stones in a closed hollow bamboo tube which the buyer was allowed to shake and, from the sound emitted, to estimate the value of the contained stones. It is needless to say that the prices realised by such fantastic sale methods were always very low.

It is necessary to exercise very great care when buying parcels of uncut stones in Siam, as many of them will be found to contain quite a considerable admixture of synthetic corundum faked to represent waterworn stones, and even natural crystals. Cut synthetic stones are also to be found in plenty as traps for the unwary, while pale blue synthetic corundum is frequently offered as cut blue zircon.

– J.F. Halford-Watkins, 1934, The Book of Ruby and Sapphire

I clearly remember my first journey to Chanthaburi's gem mines. The year was 1979. Hiring an old Chevrolet taxi at the market, I gave the driver a simple instruction: "to the mines!" And so it was that we set off, through rubber plantation and jungle lair, shortly arriving at what I now know to be Khao Ploi Waen. There, a handful of miners were found sinking pits into the red lateritic soil in search of gems.

Wow! The mines, at last! Ten thousand miles from home, we were the only "foreigners" in the area [re: no others seen in our 15-minute survey of Chanthaburi's market], and I, with my four weeks of gemological training, was ready to do some major fleecing of the naïve natives who—while they might be driving Chevys and had been digging sapphire for centuries—were obviously clueless regarding big questions like the price of fine blues in New York.

OK, dammit, I admit I had never actually been to New York, let alone its gem district, but I was American, and this superior designation on my passport conferred upon me many privileges, including the rightenty of certitude.

Where was I? The mines, of course. We watched with fascination as bucket after bucket of rich gem-bearing earth was hoisted, and already knew what each contained, having seen the glittering gems displayed in the small lozenge boxes that ladies along the road had shown us the moment we had exited our cab.

Wow, doing it now! Alex, Polo, Tav, Ralph-effin-Fitch—you rank amateurs got nothing on me, baby! Whipping out my newly acquired loupe, I ventured a gander at one particularly beautific bauble. Georg--gorgeous. Picking up another, again, outstanding.

Somewhere between calculating how I would spend my third and tenth billion, the coin caught in the slot. A mere glitch, a momentary loss of fiduciary coordination. Not disturbing (now buying second Benz...), but enough to look again. What? UUUUVVVV gotta be kiddddnnn meeeeeeee. Just a crease, a seam, a slip of the bra (my baby's skin shows that mark all the time)... noooooooo. Yesssssssss. Though I'd spent plenty of time with ladies in the night and could spot silicon from a thousand paces, I nearly missed these falsies in the bare noonday light. Bra back on, back in the Chevy, back on the bus, hang head in back of bus, back to Bangkok. No billions, no Benz. What I had found was a serious girdle crease. The gems were doublets. Looking back, I had to admit that a few of them natives were not so "naïve" after all. I was such a tender blossom; although the game was as old as time, I very nearly missed the pea.

Pit miners at Khao Ploi Waen, ca. 1980. While the mine was real, the cut stones being sold just off camera were anything but, consisting of doublets made of thin slices of natural green sapphire on top of Verneuil synthetic corundum. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Pit miners at Khao Ploi Waen, ca. 1980. While the mine was real, the cut stones being sold just off camera were anything but, consisting of doublets made of thin slices of natural green sapphire on top of Verneuil synthetic corundum. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Cutting remarks

Of course, by no means was Thailand (then Siam) the only source of gem scams, as Halford-Watkins noted again in 1934:

In 1914, the annual output for synthetic corundum was, as far as could be ascertained, about four million carats, which was even then regarded with alarm as being enormous. It grew to be such a menace to the trade in genuine rubies that in 1923 the writer had to take up the matter of its importation into India with the Government, and his investigations then led him to estimate that the consumption in Southern India alone must have been in excess of twenty million carats a year. In Trichinopoly there was a long narrow street entirely given over to the ruby cutting industry in which some five hundred cutters alone daily laboured, in addition to polishers and other assistants. In 1921, these men were all engaged in working genuine third- and fourth-grade rubies, and it was almost impossible to find a synthetic stone in the city. Two years later, these men were cutting nothing but synthetic material and it was very hard indeed to find a genuine ruby or sapphire in Trichi. Synthetic stones could be freely purchased for the equivalent of two pence a carat in the rough, and from four to eight pence a carat for the other centres. The majority of this cut stuff was disposed of locally in India, but a great deal of it was eventually shipped to Rangoon, Colombo, Singapore, and Java. The raw material entered India by post to Calcutta, Bombay, and Madras, but the majority came through Pondicherry. The following year, about two-thirds of the workmen had returned to cutting genuine stones, and the synthetic material, although still plentiful, was not nearly so prominent. Far less people are employed in this trade today, but of the total cutting done, about thirty percent of it is still synthetic material.

– J.F. Halford-Watkins, 1934, The Book of Ruby and Sapphire

|

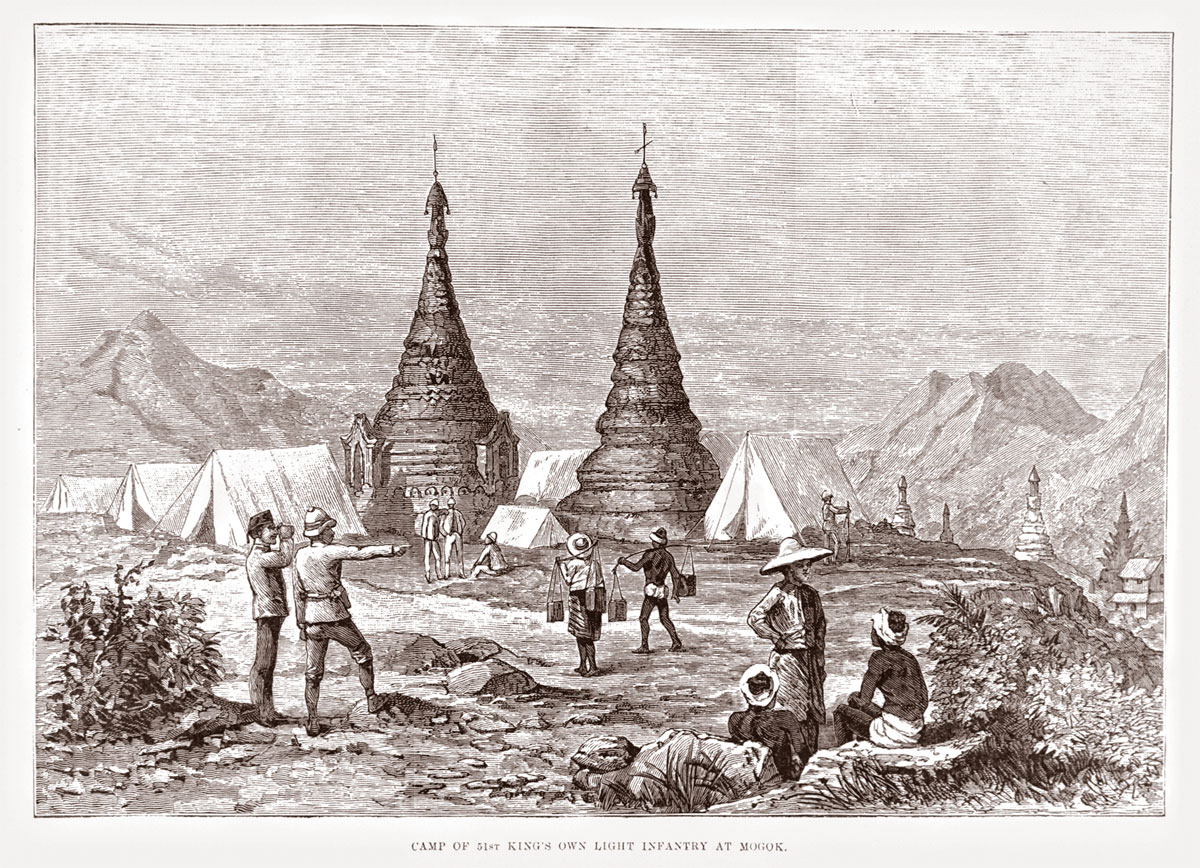

Imperial Order of the Boot While it was often the white man being taken, it cannot be said that the arrival of the white man precipitated the problem. Witness the following from Captain W.N. Lloyd, who along with G.S. Streeter (son of famed London jeweler, Edwin Streeter), was on the first British expedition to Mogok in 1886–87: As regards the Ruby Mines themselves, they have not as yet passed into the hands of Mr. Streeter, but terms will soon be agreed upon between that gentleman and the government. Meanwhile the Shans can work the mines by obtaining a licence from our political officer, who imposes a tax of 25 per cent. on all stones sold. The Ruby mines are of four kinds: the most valuable and productive being gullies formed by the action of the water on the sides of the hills; next to these come the mines formed by shafts sunk into the hill side, and lastly, wells which are sunk in the valley, and are of two descriptions, namely, the deep (20 feet) and the shallow (4 feet), where the first ruby-bearing stratum is found. Few, if any, good rubies have been shown to us since our arrival; stones of value are, I fancy, sent direct to the Mandalay market; but rubies and stones of sorts are offered for sale ad infinitum, and you will scarcely believe it, that here, at the very mines themselves, glass is palmed off on the unwary! I hear on the best authority, that our Post Office officials opened a large packet addressed to the Ruby Mines, expecting to find percussion caps, but to their astonishment the contents proved to be rubies from Birmingham! It is stated that a Shan merchant having disposed of £5000 worth of rubies in England, at once invested £2000 in glass. Only last week two beautiful looking rubies (?) were handed to me for sale, but with Mr. Streeter's assistance I was not only able to pronounce them as glass, but at the same time invested the wily Shan, who presented them, with the Imperial order of "the boot!" Captain W.N. Lloyd Note that prior to this British expedition, only a tiny handful of Europeans had ever ventured into the Mogok region. No, the red glass that Mogok natives tried to off on the British was not there waiting for the white man, but had been put into practice long before, fleecing those of color, too. |

British camp at Mogok. (From the Illustrated London News, 19 Feb., 1887). Click on the image for a larger version.

British camp at Mogok. (From the Illustrated London News, 19 Feb., 1887). Click on the image for a larger version.

|

Down the drain – Mining Bangkok's alluvials For much of Asia's population, life is a constant battle for survival. But few have it tougher than those Bangkok residents whose job it is to climb down into sewers and drains and cleanse them of society's offal and castaways.

Work begins at dawn, with the removal of the first grating. Down someone goes, a blackened rope the only lifeline to the world above. Even at street level, the stench makes one wince. But he is beyond smell, beyond light. Slowly he moles into the dark, tugging the rope. Eventually, the charcoal form slowly emerges from another drain a few paces away. One hand still clutches the rope, but the other's fingers wrap even more tightly around a different buoy – a small bag of debris collected along the way. He has been mining the city's alluvials and, like those upcountry, the heavies are the most valuable. So it goes, until the sun's last rays force their way into Bangkok's acetylene sunset. Then the day's production is laid out on a soiled blanket. A few swipes with a blackened toothbrush bring forth life, luster. Here a fragment of silver, there a bit of gold and, if it has been a particularly good day, a scrap of jewelry. Passersby bend down to examine the finds. One pays particular attention to a silver coin. With the toothbrush, he slowly works away the years of grime and, as he does so, his mind's eye smiles. It is a rare coin from the colonial days, much sought-after by local collectors. Quickly mixing it into a pile of common coins, the haggling begins. They finally settle on 900 baht – a fraction of the actual value. No matter how low the drain cleaner's caste, in the end, he manages some dignity. That, and a few more baht, a bit of sweet relief, a bit of light at the end of the tunnel, until the next day's descent. As the customer walks away, the drain cleaner also smiles inside. He thinks he'll get a few more of those coins from that Chinatown workshop where they are made. They seem to be popular. – Richard W. Hughes, 1997, Ruby & Sapphire |

Dick's Law

I think by now it is clear that many tender blossoms, newly initiated into the gem trade, are under the impression that the peasant natives of Southeast Asia are, in the main, fools. The natives are thought to wander the jungles with pockets bulging from the weight of valuable rubies, in search of foreigners whom might be willing to lighten their load in exchange for colored beads or, perhaps, a digital wristwatch. Reality sets in when, back home, the purchases prove to be cleverly-disguised Verneuil synthetics. This brings us to the main purpose of this essay—Dick's Law—which reads as follows:

Basic Statement

The closer you get to the mines, the more fakes you find.

Postulate No. 1

The quality of said fakes (ease of deception) varies inversely with the distance from the mines, being expressed by the following formula, where d = distance from the mines, q1 = ease of deception, and k1 = Dick's constant.

q1 = k1/d

Postulate No. 2

Quantity of fakes also varies inversely with d, as expressed by the following formula where q2 = quantity.

q2 = k2/d

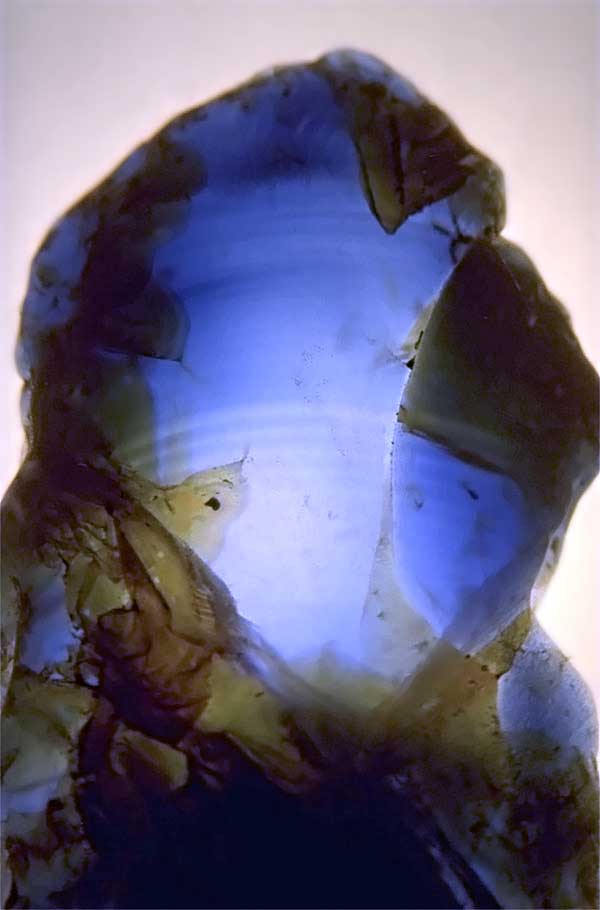

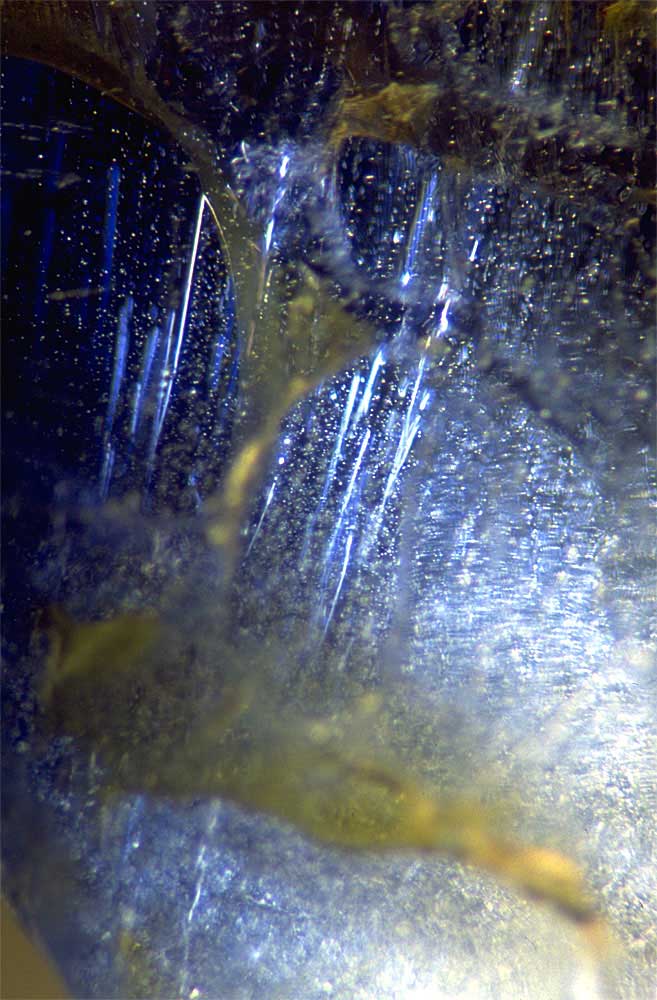

One need look no further for proof of Dick's Law than the images below. Southeast Asian con artists know that, unlike many natural blue sapphires, no Verneuil synthetic product exists where both blue and yellow are found in the same stone. They also know that, if you are an experienced dealer worth your sapphire, you know that, too. Thus in order to give us interesting stories to tell our children, those clever people take fragments of Verneuil synthetic rough and, after a good tumbling to give the appearance of alluvial wear, apply yellow stains to the outside and into fractures. When you hold that sucker up to the light to check color distribution, you're rewarded with the sight of yellow and blue banding in the same crystal—obviously natural.

Top: Verneuil synthetic blue sapphire rough which has been tumbled, fractured and stained yellow to resemble natural rough.

Lower left: Curved color banding is clearly visible with immersion.

Lower right: Yellow stains in the cracks are clearly visible, as are the multitudes of gas bubbles.

Photos: Tony Laughter. Click on the images for larger versions.

The above stone was found in Bangkok, but for the really good fakes, you've got to go to the mines. Witness the following tale from GIA Field Gemologist, Vincent Pardieu. On a May 2009 trip to the Luc Yen deposits of Vietnam, he asked if anyone had deep blue spinel for sale. After a day spent shooting blanks, Pardieu had just bought a nice specimen from a local dealer at the mines and, to his surprise, she said she still had two tiny pieces of the best blue spinel from a parcel she had bought a few years prior from a miner. While she was keeping them as color samples, since he was a really swell guy, she would consent to sell them to him for study if he was interested. Several minutes later, she was back and two small cobalt-blue beauties winked up at him. Perfect research specimens! They agreed on a price ($5) and each parted with a smile on their face.

Returning to Bangkok, Pardieu analyzed one piece, which was a classic natural cobalt-colored spinel. But when the results came back on the second, he got a shock: it was synthetic!

These two blue spinels were purchased by the GIA's Vincent Pardieu in Vietnam's Luc Yen mining district. Price paid was $5. While one turned out to be a rare natural cobalt-colored spinel, the other proved to be synthetic. Photo: Vincent Pardieu/Fieldgemology.org

These two blue spinels were purchased by the GIA's Vincent Pardieu in Vietnam's Luc Yen mining district. Price paid was $5. While one turned out to be a rare natural cobalt-colored spinel, the other proved to be synthetic. Photo: Vincent Pardieu/Fieldgemology.org

Monkey see, monkey do

There we have it, both empirical and mathematical proof of Dick's Law. Thus the next time you find yourself in some dusty Third-World backwater, about to take that poor naïve native for a ride, remember one thing: q2 = k2/d. And also remember the [naîve/dirty/unsophisticated/ignorant/infidel] native commonly has the same low [naîve/dirty/ unsophisticated/ignorant/infidel] opinion of you.

In the end, I think we will all do well to remember the following. Synthetic gems were not invented in the East, and when it comes to many treatments, we have a similar trail of evidence that leads not to the Orient, but to the more technologically advanced West. After all, it was Pliny who said two thousand years ago:

…Moreover, I have in my library certain books by authors now living, whom I would under no circumstances name… containing, for example, information on how to make a sardonychus [sardonyx] from a sarda [carnelian, in part sard]: in other words, how to transform one stone into another. To tell the truth, there is no fraud or deceit in the world that yields greater gain and profit than that of counterfeiting gems.

– Pliny [23–79 AD]

The point is not East is East and West is West and never the twain shall meet. From Africa to Europe, South America to Asia, indeed from all points of the compass, identical motivations are at play.

Recently I found myself at a Hindu temple in Darjeeling (India), surrounded by monkeys who displayed behavior not unlike that of members of my own race. The strong bullied the weak, the old were teased by the young. And mothers cared for and protected their children.

Life is thus. So it always has been. So it will probably always be. When it comes down to it, we are but a strange tribe of monkeys fighting over bananas.

References & further reading

- Halford-Watkins, J.F. (1934) The Book of Ruby and Sapphire. London, unpublished manuscript, 256 pp.

- Hughes, R.W. (1997) Ruby & Sapphire. Boulder, CO, RWH Publishing, 512 pp.

- Illustrated London News (1886–1887) [The ruby mines of Burmah]. Illustrated London News, London, 1886: Jan. 16, p. 1; 1887: Jan. 22, p. 89; Feb. 19, pp. 205–206; Feb. 26, p. 227; Aug. 6, pp. 149–150; Aug. 27, p. 246; Sept. 3, p. 270; Oct. 15, pp. 453–454; Nov. 19, p. 713.

- Kipling, R. and Balestier, C.W. (1892) The Naulahka: A Story of West and East. New York, MacMillan and Co.

- Lloyd, W.N. (1888) The expedition to the ruby mines of Upper Burma (a short sketch). Minutes of Proceedings of the Royal Artillery Institution, Vol. XV, pp. 435–441.

- Twain, M. (1897) Following the Equator. Hartford, CT, American Publishing Co., 720 pp.

- Wikipedia (n.d.) Thai gem scam.

About the author

Richard W. Hughes is one of the world’s foremost experts on ruby and sapphire. The author of many books and over 170 articles, his writings and photographs have appeared in a diverse range of publications, and he has received numerous industry awards. Co-winner of the 2004 Edward J. Gübelin Most Valuable Article Award from Gems & Gemology magazine, the following year he was awarded a Richard T. Liddicoat Journalism Award from the American Gem Society. In 2010, he received the Antonio C. Bonanno Award for Excellence in Gemology from the Accredited Gemologists Association. The Association Française de Gemmologie (AFG) in 2013 named Richard as one of the Fifty most important figures that have shaped the history of gems since antiquity. In 2016, Richard was awarded a visiting professorship at Shanghai's Tongji University. 2017 saw the publication of Richard and his wife and daughter's Ruby & Sapphire • A Gemologist's Guide, arguably the most complete book ever published on a single gem species and the culmination of four decades of work in gemology. In 2018, Richard was named Photographer of the Year by the Gem-A, recognizing his photo of a jade-trading market in China, while in 2020, he was elected to the board of directors of the Accredited Gemologists Association and was appointed to the editorial review board of Gems & Gemology and The Australian Gemmologist magazine. In 2022, Richard published Jade • A Gemologist's Guide, while 2024 brought Broken Bangle • The Blunder-Besmirched History of Jade Nomenclature. His jade trilogy was completed in 2025 with his translation of Heinrich Fischer's Nephrite and Jadeite.

Notes

Penned and posted in May, 2010.