A brief history of Burmese (Myanmar) sapphires, along with details of some of the major pieces of yore.

Introduction to Burmese Sapphires

Although it is rubies for which Burma (Myanmar) is famous, some of the world's finest blue sapphires are also mined in the Mogok area. Today the world gem trade recognizes the quality of Burmese sapphires, but this was not always the case.

Edwin Streeter (1892) described Burmese sapphires as being overly dark. Unfortunately this error was later repeated by Max Bauer and others. G.F. Herbert Smith wrote…

While the Burma ruby is famed throughout the world as the finest of its kind the Burma sapphire has been ignominiously, but unjustly, dismissed as of poor quality. In actual fact nowhere in the world are such superb sapphires produced as in Burma.

— G.F. Herbert Smith, Gemstones, 1972

While this statement must be qualified by adding that the finest Kashmir sapphires are in a class by themselves, those from Burma are also magnificent. Former head of the Geological Survey of India, J. Coggin Brown (1955), said this:

It has been stated that Burmese sapphires as a whole are usually too dark for general approval, but this is quite incorrect; next to the Kashmir sapphires they are unsurpassed. Speaking generally, Ceylon sapphires are too light and Siamese sapphires too dark, and it is more than probable that many of the best 'Ceylon' stones first saw the light of day from the mountainsides of the Mogok Stone Tract.

— J. Coggin Brown, India's Mineral Wealth, 1955

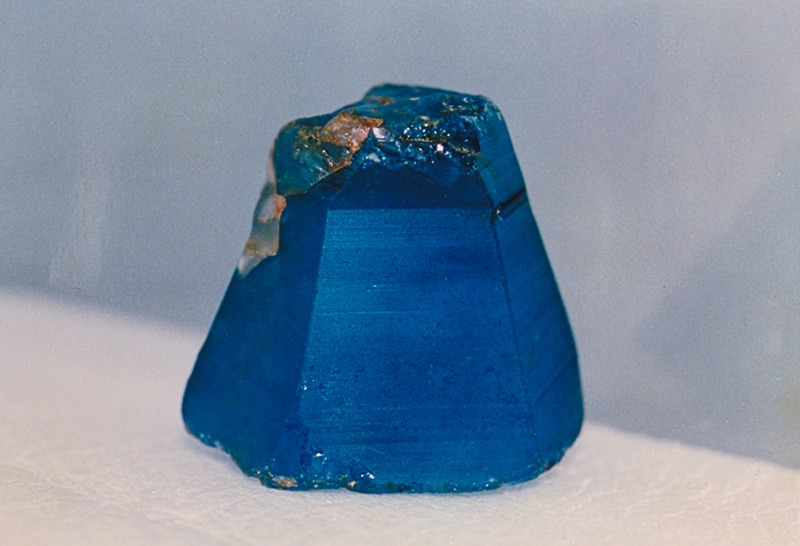

21.42 carats of Burmese true-blue mystery. This stone is an example of Mogok's finest product.

21.42 carats of Burmese true-blue mystery. This stone is an example of Mogok's finest product.

Not all Burma sapphires are deep in color. The best display a rich, intense, slightly violetish blue, but some are quite light, similar to those from Sri Lanka. The key difference between Burma and Ceylon sapphires is saturation, with those from Burma possessing much more color in the stone. Color banding, so prominent in Ceylon stones, may be entirely absent in Burma sapphires.

Burmese Sapphires

Although rubies are found with much greater frequency at Mogok (rubies form about 80–90% of the total output), sapphires may reach larger sizes. Cut gems of over 100 carats are not unknown. Large fine star sapphires are also found at Mogok, in addition to star rubies. Near Kabaing (Khabine), at Kin, is located a mine famous for star sapphires.

The sapphires of Burma occur in intimate association with rubies in virtually all alluvial deposits throughout the Mogok area, but are found in quantity at only a few localities, particularly 8 miles (13 km) west of Mogok, near Kathé (Kathe). At Kyaungdwin, near Kathé, in 1926 a small pocket was discovered that yielded "many thousand pounds' [sterling] worth of magnificent sapphires within a few weeks." (Halford-Watkins, 1935b)

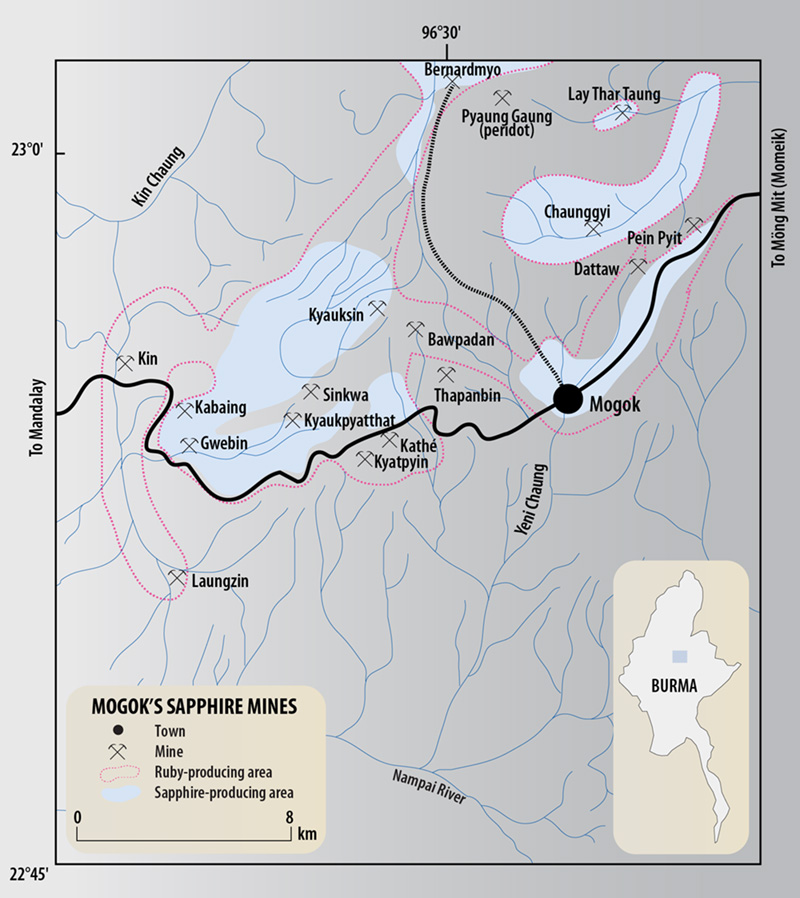

According to Halford-Watkins (1935b), the majority of fine sapphires were derived from the area between Ingaung and Gwebin. Sapphires have also been found near Bernardmyo: [1]

Bernardmyo itself at one time produced large quantities of sapphires, many of which were of magnificent colour and quality, though a number were of a peculiar indigo shade, which appeared either very dark or an objectionable greenish tint by artificial light. During an extensive native mining rush to Bernardmyo in 1913 a number of these stones were placed on the London market.

Many of the stones found in this area were coated with a thin skin of almost opaque indigo colour which, on being ground off, revealed a centre sometimes of a fine gem quality, but in many cases of greenish shade. The method of occurrence was different from that anywhere else as the majority of stones were taken from a hard black iron-cemented conglomerate, which was found layers a few inches thick, often only a few feet below the surface. This area now appears to be exhausted, and little mining is carried on there to-day except for peridots, which are abundant.

Another isolated local deposit which has produced some fine sapphires occurs at Chaungyi, four miles north of Mogok, and about a thousand feet higher.

— J.F. Halford-Watkins, 1935b

Map of the sapphire-producing regions of Burma's Mogok Stone Tract.

Map of the sapphire-producing regions of Burma's Mogok Stone Tract.

Other than blue, sapphires also occur in violet, purple, colorless and yellow colors at Mogok. The violet and purple stones may be fine; yellows tend to be on the light side and are not common. Green sapphires are known, but rare.

Sapphire mine of U Mya Mg at Khabine, near Gwebin, Mogok, Burma. In February of 1994, this mine yielded the 502-ct sapphire crystal in Figure 6.

Sapphire mine of U Mya Mg at Khabine, near Gwebin, Mogok, Burma. In February of 1994, this mine yielded the 502-ct sapphire crystal in Figure 6.

Rough Orientation

Orientation of sapphires from Mogok is important. While stones from localities such as Kyauk Pyat That retain their rich blue hue in various orientations, those from Chaunggyi and Painpyit take on a greenish tint when the c axis is not exactly perpendicular to the table. Many Mogok dealers attribute this phenomena to "invisible black silk," and pay strict attention to locality when buying sapphire rough (U Hla Win, pers. comm., 2 Sept., 1994).

Famous Burmese Sapphires

SM Tagore in his classic work, Mani-Málá (1879, 1881), describes several celebrated sapphires. One of these was a fabulous stone of 951 cts, and was seen by an English ambassador to the Court of Ava (Burma). Tagore also mentions a curious custom among the Hindus of India. They were said to have a prejudice against sapphires, believing the blue gem to be the bringer of misfortune:

In consequence of this notion, some of them would invariably keep a stone on trial for several days before they would make final settlement with the sellers. Hence, perhaps, the paucity in the numbers of Sapphires in their possession.

— SM Tagore, Mani-Málá, 1879

One magnificent Gwebin gem was scratched up just below the grass in 1929 by miners preparing a site for digging. Found by U Kyauk Lon (U Hla Win, pers. comm., May 2, 1994), it was a water-worn, doubly-truncated pyramid weighing an incredible 958 cts. Purchased for $13,000 by Albert Ramsay, who dubbed it the "Gem of the Jungle," the rough produced nine fine cut stones, weighing 66.53, 20.11, 19.19, 13.15, 12.29, 11.39, 11.18, 5.57, and 4.39 cts. All stones were personally cut by Ramsay and were said to be of exceptional color. A marvelous account of the purchase and cutting of the Gem of the Jungle was published in the Saturday Evening Post in 1934 (Ramsay and Sparkes, 1934).

|

|

| Left: U Tun, one of the most prominent sapphire dealers in Mogok in colonial times. Right: U Thein, one of the brothers who mined sapphires at Lay Thar Taung. (Photos: U Khin Mg Win, Mogok) |

|

About 1967, a 12.6-kg (63,000 ct) crystal surfaced at Mogok. Today this sapphire colossus is on display at the Myanma Gems Enterprise (MGE) museum in Yangon. Like virtually all giant specimens, it is far from gem quality. In order to see if something of gem quality might be lurking within, MGE staff disemboweled it with drill and saw. Alas, the interior was just as opaque as the skin (see Figure 6). While this piece is billed by MGE as the "world's largest sapphire crystal," in fact a number of much larger specimens are known, including a 40.3 kg crystal from Sri Lanka which contains gemmy portions (see Table 2).

The 12.6-kg sapphire giant owned by Myanma Gems Enterprise. Note the large central piece which was removed in an attempt to see if gem material might lie within. (Photos: U Khin Mg Win)

The 12.6-kg sapphire giant owned by Myanma Gems Enterprise. Note the large central piece which was removed in an attempt to see if gem material might lie within. (Photos: U Khin Mg Win)

On Feb. 22, 1994, a large sapphire of 502 cts was unearthed at Khabine, about 2.4 kms from Gwebin. The crystal is a single pyramid of rich blue color, and slightly silky (see Figure 7).

Top: 502-ct Burmese sapphire crystal. This was unearthed on Feb. 22, 1994, at Khabine, near Gwebin, in Burma's Mogok Stone Tract.

Top: 502-ct Burmese sapphire crystal. This was unearthed on Feb. 22, 1994, at Khabine, near Gwebin, in Burma's Mogok Stone Tract.

Below: The base of the crystal, showing concentrations of silk. (Photos: U Khin Mg Win)

Table 1 is an admittedly weak attempt to catalog some of the more famous Burmese sapphires. Criteria for being listed includes titled specimens, specimens large or fine enough to merit mention in newspaper/magazine articles, and those which have set auction records. Unfortunately, due to the secretive nature of the gem business, many fine specimens have never been publicly described. The authors would love to hear from readers with additional information.

| Name, weight, description and sale price* | Source & date found | Current location | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ruspoli’s Sapphire (“Wooden Spoon Seller’s Sapphire” or “Great Sapphire of Louis XIV”) 135.8 cts; faceted; rhomb shaped (only six facets); said to have been found by a wooden spoon seller in Bengal; sold by the House of Ruspoli (Rospoli?) of Rome to a German prince (salesman?), who in turn sold it to the French jeweler Perret for 170,000 francs. Later purchased by Louis XIV. |

Said to be Bengal; probably from Burma or Sri Lanka Date unknown |

Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris Valued at £100,000 in 1791 |

Tagore, 1879, 1881 Streeter, 1892 Bank, 1973 H.-J. Schubnel (pers. comm., 16 Dec. 1994; 5 Jan. 1995) |

| Unnamed 951 cts; rough or cut unknown; seen in 1827 in the treasury of the king of Ava |

Unknown (Burma?) Date unknown |

Unknown | Smith, 1913 |

| Unnamed Rough, weight unknown; sold for Rs 28,000 (£1,870) |

Redhill Mine Mogok, Burma 1917 |

Unknown | Times of London, 11 Jul 1917 |

| Unnamed 113 cts; rough; sold for Rs 45,000 |

Bernardmyo, Mogok, Burma 10 May 1919 |

Unknown | Times of London, 15 Jul 1919 |

| Unnamed Weight unknown; rough; sold for Rs 40,000 |

Mogok, Burma 1919 |

Unknown | Times of London, 15 Jul 1919 |

| Unnamed 437 cts; not stated whether rough or cut; valued at over £11,000 |

Mogok, Burma 1928 |

Unknown | Mineral Industry, 1929 |

| Gem of the Jungle 958 cts rough; cut stones of 66.50 (66.53?), 20.25, 20.00, 13.11, 12.25, 11.33, 11.11, 5.50 and 4.33 cts; purchased by Albert Ramsay for over £13,000 |

Gwebin, Mogok, Burma Aug 1929 (or Jul 1930) |

Unknown | Mineral Industry, 1930 Mineral Industry, 1931 Ramsay et al., 1934 Halford-Watkins, 1935a |

| Star of Asia 330 cts; cabochon cut; blue-violet star sapphire; acquired in 1961 from Martin Ehrmann; once said to belong to the Maharaja of Jodhpur |

Burma Date unknown |

Smithsonian | Desautels, 1972 White, 1991 |

| Unnamed 630 cts rough (upon breaking up for cutting, it proved less valuable than expected) |

Kathé Mogok, Burma May 1930 |

Unknown | Times of London, 31 May 1930 Mineral Industry, 1930, 1932 Brown, 1933 |

| Unnamed 293 cts rough |

Kathé Mogok, Burma 1930 |

Unknown | Brown, 1933 |

| Unnamed nearly 1000 cts rough |

Gwebin, Mogok, Burma 12 Aug 1932 |

Unknown | Brown, 1933 |

| Unnamed 514 cts; rough |

Mogok, Burma Dec 1932 |

Unknown | Brown, 1933 |

| Unnamed star sapphire 435 cts; not known whether rough or cut |

Kathé, Mogok, Burma 1932 |

Unknown | Mineral Industry, 1934 |

| Unnamed 390 cts; rough; sold for over £3,000 |

Mogok, Burma 1930s |

Unknown | Halford-Watkins, 1935b |

| Unnamed ~99 cts; faceted; round; offered for sale in Bangkok in early 1980s for $10,000/ct |

Burma Date unknown |

Unknown | Author (RWH) |

| Unnamed 41.04 cts; faceted; emerald cut; sold at Sotheby’s New York, Oct 1986 for $924,000 ($22,515/ct) |

Burma Date unknown |

Purchased by American retailer | Anonymous, 1986 |

| Rockefeller Sapphire 62.02 cts; faceted, rectangular step cut; mounted in diamond ring; sold at Sotheby’s St. Moritz, 20 Feb 1988, for $2,828,546 ($45,607/ct). Former per-carat and total price world record for a single blue sapphire. |

Burma Date unknown |

Unknown | Hughes et al., 1988 Matthews, 1993 |

| Unnamed 4145 cts; rough; offered for sale at 1993 Myanma Gems Enterprise Emporium (Lot 95; reserve price $300,000) |

Burma Date unknown |

Unknown | U Hla Win, pers. comm., 2 Sept 1994 |

| Unnamed 14,387 cts; rough; offered for sale at 1993 Myanma Gems Enterprise Emporium (Lot 96; reserve price $50,000) |

Burma Date unknown |

Unknown | U Hla Win, pers. comm., 2 Sept 1994 |

| Unnamed 502 cts; rough, pyramid-shaped crystal, silky, of good color |

Kabaing, Mogok, Burma 22 Feb 1994 |

Unknown | U Hla Win, pers. comm., 22 Jun 1994 |

| * On 1 April 1914, the carat was standardized as 200 milligrams. Weights before that date are approximate only. All prices are in US dollars unless stated otherwise. [ return to top of table ] | |||

| Name, weight, description and sale price* | Source & date found | Current location | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unnamed 312 lb (141.5 kg; 707,500 cts); opaque, red and blue crystal |

Franklin, NC Before 1882 |

Shepard Collection Amherst College, USA |

Kunz, 1892 |

| Unnamed Over 10 lb (4.5 kg); sapphire crystal |

Mogok, Burma 1928 |

Unknown | Mineral Industry, 1929 |

| Unnamed 335 lb (152 kg); hexagonal bipyramid crystal (not gem quality); 2 ft, 3 in (68.58 cm) in width. This is the largest known corundum crystal on record. |

Leydsdorp, Northern Transvaal, South Africa Date unknown |

Geological Survey Museum, Pretoria, South Africa | Spencer, 1933 Anonymous, 1951 |

| Unnamed 42 lb (19 kg); crystal said to be in the shape of the island of Sri Lanka |

Sri Lanka Date unknown |

American Museum of Natural History? | Anonymous, 1936 Wijesekera, 1980 |

| Unnamed 34 lb (15.42 kg); crystal |

Source unknown Date unknown |

British Museum | Anonymous, 1951 |

| Unnamed 63,000 cts (12.6 kg; 27.783 lb); rough crystal, bluish gray pyramid (not gem quality); 27 × 14.25 × 6.75 in (68.58 × 36.195 × 17.145 cm) |

Mogok, Burma ca. 1967 |

Myanma Gems Enterprise, Burma | Anonymous, 1967 |

| Unnamed 40.3 kg; rough, doubly-terminated bipyramid crystal |

Rakwana, Sri Lanka Date unknown |

Unknown | Koivula and Kammerling, 1989 |

| Unnamed 4,230 cts; rough; bluish bipyramidal crystal; not gemmy |

Lokekhet (“Kadegadar”) Mogok, Burma Sept. 1990 |

Myanma Gems Enterprise, Burma | Working People’s Daily, 5 Feb 1991 Clark, 1991, p. 68 |

| * On 1 April 1914, the carat was standardized as 200 milligrams. Weights before that date are approximate only. All prices are in US dollars unless stated otherwise. [ return to top of table ] | |||

About the author

Richard W. Hughes is one of the world’s foremost experts on ruby and sapphire. The author of many books and over 170 articles, his writings and photographs have appeared in a diverse range of publications, and he has received numerous industry awards. Co-winner of the 2004 Edward J. Gübelin Most Valuable Article Award from Gems & Gemology magazine, the following year he was awarded a Richard T. Liddicoat Journalism Award from the American Gem Society. In 2010, he received the Antonio C. Bonanno Award for Excellence in Gemology from the Accredited Gemologists Association. The Association Française de Gemmologie (AFG) in 2013 named Richard as one of the Fifty most important figures that have shaped the history of gems since antiquity. In 2016, Richard was awarded a visiting professorship at Shanghai's Tongji University. 2017 saw the publication of Richard and his wife and daughter's Ruby & Sapphire • A Gemologist's Guide, arguably the most complete book ever published on a single gem species and the culmination of four decades of work in gemology. In 2018, Richard was named Photographer of the Year by the Gem-A, recognizing his photo of a jade-trading market in China, while in 2020, he was elected to the board of directors of the Accredited Gemologists Association and was appointed to the editorial review board of Gems & Gemology and The Australian Gemmologist magazine. In 2022, Richard published Jade • A Gemologist's Guide, while 2024 brought Broken Bangle • The Blunder-Besmirched History of Jade Nomenclature. His jade trilogy was completed in 2025 with his translation of Heinrich Fischer's Nephrite and Jadeite.

U Hla Win is a Yangon-based gem dealer and writer.

Acknowledgments

U Hla Win would like to give thanks to U Thu Daw for educating him about Burmese sapphires, and to U Khin Mg Win for the photographs.

Richard Hughes would like to thank Bob Frey, expert in various things Chinese and founding member of HAW HAW, who has gone above and beyond the call of duty in both editing and locating obscure references.

Footnotes

1. The plateau of Bernardmyo was chosen by the first British expedition to Mogok as a suitable place for a sanitarium for British troops. It was thought that the climate was more suitable for Europeans and that eventually the place would develop into the Simla of Burma. Bernardmyo was christened after the first British Chief Commissioner of Upper Burma, Sir Charles Bernard (GS Streeter, 1887, 1889). [return to article]

Notes

This article was based in part on an excerpt from my 1997 book, Ruby & Sapphire. It was published in 1995 in the Journal of Gemmology (Vol. 24, No. 8, October, pp. 551–561). I was able to meet U Thu Daw during my first visit to Mogok in 1996. Sadly, he passed away shortly thereafter. This web version is altered slightly from the print version.

References

- Anonymous (1936) Largest sapphire to be cut. The Gemmologist, Vol. 5, No. 58, p. 247; RWHL.

- Anonymous (1937) Cutting the Great Burma Sapphire. The Keystone, September, pp. 130–131; RWHL*.

- Anonymous (1951) Famous sapphires. The Gemmologist, Vol. 20, No. 240, p. 165; RWHL*.

- Anonymous (1967) Gemological Digests: World's largest star sapphire. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 12, No. 5, Spring, p. 158; RWHL.

- Anonymous (1986) Sotheby's sets records with ruby and diamond. Jewelers' Circular-Keystone, December, p. 75; RWHL*.

- Bank, H. (1973) From the World of Gemstones. Trans. by E.H. Rutland, Innsbruck, Pinguin-Verlag, 178 pp.; RWHL.

- Brown, J.C. (1933) Ruby mining in Upper Burma. Mining Magazine, June, pp. 329–340, RWHL*.

- Brown, J.C. and Dey, A.K. (1955) India's Mineral Wealth. 2nd ed., Bombay, Oxford University Press, 761 pp., RWHL*.

- Clark, C. (1991) Burma Emporium: The ultimate treasure hunt. JewelSiam, No. 2, April-May, April/May, pp. 58–71; RWHL.

- Desautels, P.E. (1972) Gems in the Smithsonian. Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution Press, 63 pp.; RWHL.

- Halford-Watkins, J.F. (1935a) Burma sapphires – in defense of a much-abused name. The Gemmologist, Vol. 5, No. 50, September, pp. 39–43, RWHL*.

- Halford-Watkins, J.F. (1935b) Burma sapphires – locations and characteristics. The Gemmologist, Vol. 5, No. 52, November, pp. 89–98, RWHL*.

- Hughes, R.W. and Sersen, W.J. (1988) Bangkok Gem Market Review. Gemological Digest, Vol. 2, Nos. 1 & 2, pp. 20–22, RWHL.

- Koivula, J.I. and Kammerling, R.C. (1989) Gem News: Huge, doubly-terminated sapphire crystal. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 25, No. 4, Winter, p. 247; RWHL.

- Kunz, G.F. (1892) Gems and Precious Stones of North America. Reprinted by Dover, 1968 (367 pp.), New York, The Scientific Publishing Co., 336 pp., RWHL*.

- Matthews, P., ed. (1993) The Guinness Book of Records 1993. New York, Bantam Books, 847 pp.; RWHL.

- Mineral Industry (1893–1942) Precious and semi-precious stones [famous gems]. In The Mineral Industry, its Statistics, Technology and Trade During…, Ed. by G.F. Kunz and G.A. Roush, New York, McGraw-Hill, 1924: pp. 579–582; 1929: pp. 532–534; 1930: pp. 549–550; 1931: pp. 524–525; 1932: pp. 478–479; 1934; pp. 508–509; 1935: p. 508; 1942: p. 483; RWHL.

- Ramsay, A. and Sparkes, B. (1934) Bright jewels of the mine, parts 1–3. Saturday Evening Post, Parts 1–3, 15 Sept.: pp. 10–11, 65–66, 69; 29 Sept.: p. 26, 28, 34, 36, 39; 20 Oct.: pp. 26–27, 76, 78, 80; RWHL*.

- Smith, G.F.H. (1913) Gem-Stones and their Distinctive Characters. London, Methuen & Co., 2nd edition (1st ed. 1912), 312 pp.; RWHL*.

- Smith, G.F.H. (1972) Gemstones. 14th edition, revised by F.C. Phillips, London, Chapman and Hall, 580 pp.; RWHL.

- Spencer, L.J. (1933) Nation acquires large ruby. The Gemmologist, Vol. 2, No. 18, pp. 176–178, RWHL.

- Streeter, G.S. (1887) The ruby mines of Burma. Journal of the Manchester Geographic Society, No. 3, pp. 216–220, map; RWHL*.

- Streeter, G.S. (1889) The ruby mines of Burma. Journal of the Society of Arts, No. 37, February 22, pp. 266–275; RWHL*.

- Streeter, E.W. (1892) Precious Stones and Gems. 5th edition, London, Bell, 355 pp., RWHL*.

- Tagore, S.M. (1879, 1881) Mani-Málá, or a Treatise on Gems. Calcutta, I.C. Bose & Co., 2 vols., 1046 pp., RWHL*.

- Times of London (1878–1933) [Important rubies and sapphires]. The Times, London, 1878, Dec. 20, p. 6d; 1880, March 5, p. 7d; March 6, p. 5e; June 22, p. 10f; Oct. 11, p. 5b; 1885, Dec. 5, p. 5; 1886, March 17, p. 5; 1889, 1917, July 11, p. 13c; 1918, July 10, 12e; 1919, July 15, p. 20a; Aug. 25, p. 9f; 1920, July 12, p. 22f; July 20, p. 20e; 1921, June 23, p. 12c; 1924, Nov. 12, p. 11b, 11g, 3*, 4*; 1930, May 31, p. 12e; 1931, June 4, p. 13g; 1932, April 27, p. 13g; 1933, Feb. 3, RWHL.

- White, J.S. (1991) The Smithsonian Treasury: Minerals and Gems. Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution Press, 96 pp.; RWHL

- Wijesekera, N. (1980) Gemstones of Sri Lanka. Lapidary Journal, October, pp. 1616–1618; RWHL.

- Working People's Daily (1991) SLORC Chairman Senior General Saw Maung inspects world's largest sapphire. Working People's Daily, Rangoon, 5 February, seen.

RWHL = References contained in the personal library of Richard W. Hughes

* = References of particular merit