A 2006 mission to remote ruby and spinel localities in Tajikistan.

Seek knowledge, even unto China. Islamic maxim

In our business, travel should be de rigueur. But the headlines frighten so many away. Boo! Earth is one giant pool of war, disease and pestilence. Boo! International travel is undertaken only by the clinically insane or those with Special Ops experience. Boo! If the pox or pollution don't gettcha, al Qaeda is close behind. As Lou Reed sang: "You've got a black .38 and a gravity knife. You still have to ride the train."

Lou was singing about the New York subways. Having braved Manhattan's dangerous tunnels, we feel qualified to discuss what some might regard as an even greater peril: travel to Tajikistan.

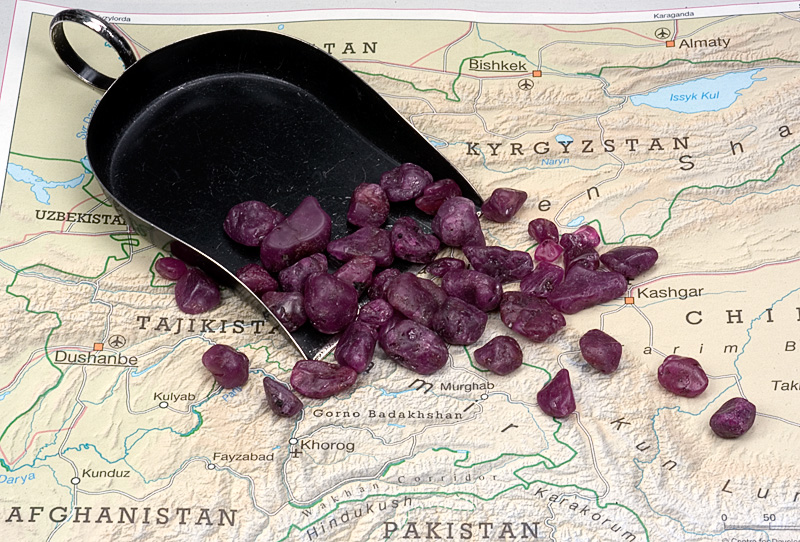

Rough ruby reputed to be from Tajikistan. It was this material which set the authors off on their quest for the source.

Rough ruby reputed to be from Tajikistan. It was this material which set the authors off on their quest for the source.

Photo © Wimon Manorotkul/Pala International

We know what you're thinking. Tajiki-where?

Tajikistan.

But Tajiki-why?

Simple. For well over a millennium, this land has held one of the most important gemological secrets, that of the balas ruby. When one of the authors (RH) began researching his first book, he became intrigued by the accounts of these mines which, despite being the alleged source of the Black Prince's Ruby and Timur Ruby, had completely slipped off the gemological radar. How could such a famous locality go so utterly MIA?

The answer is one of bad politics and worse geography. Early accounts put the locality in Badakhshan and many writers (including Hughes), assumed this meant it lay in Afghanistan. In reality, the Badakhshan region straddles both NE Afghanistan and eastern Tajikistan. And since Tsarist times, what is now Tajikistan was a strategic border region of Russia, verboten to all foreigners.

That changed with the Soviet collapse in 1989. Several of the Soviet republics demanded and were granted independence, including Tajikistan. But the newly-independent Tajikistan almost immediately entered a period of civil war, one where the eastern Gorno-Badakhshan region became both a rebel stronghold and a war zone.

Despite the war, the gemological detective work continued. By the mid-1990s, Richard Hughes and Afghan gem specialist Gary Bowersox were comparing notes. Both had independently concluded that these mines lay right along the Afghan-Tajik border, somewhere in the vicinity of Ishkashim. But where? This town was literally bisected by the Panj (Pamir) River which formed the border between the two nations.

Map of Tajikistan, showing the location of the spinel mines at Kuh-i-Lal and the ruby mines at Snezhny. Map: Richard W. Hughes

Map of Tajikistan, showing the location of the spinel mines at Kuh-i-Lal and the ruby mines at Snezhny. Map: Richard W. Hughes

It was left to Bowersox to put together the final pieces of this puzzle. On one of his annual visits to Afghanistan's hinterlands, he was able to photograph the historic mines, at a place called Kuh-i-Lal. But they lay one bridge too far, across the border in Tajikistan. Following several aborted stabs, and with the end of the civil war, Bowersox was finally able to visit the mines in the summer of 2005. In addition, that same trip he journeyed to the relatively new ruby deposits in eastern Tajikistan near the Chinese border.

Flash forward to early 2006. Sitting in Bangkok, Vincent Pardieu began to see rubies from Tajikistan. Meanwhile, Schorr and Hughes were busy planning a gem-hunting trip to the Congo, where a close friend had an in with the Minister of Corruption. Suddenly, Hughes received a chance e-mail from Tashkent offering Tajik ruby. Hmmm… By Spring, Pardieu, Hughes and Schorr were comparing notes, thinking Tajiki-why-not?

Do you know the way to Dushanbe?

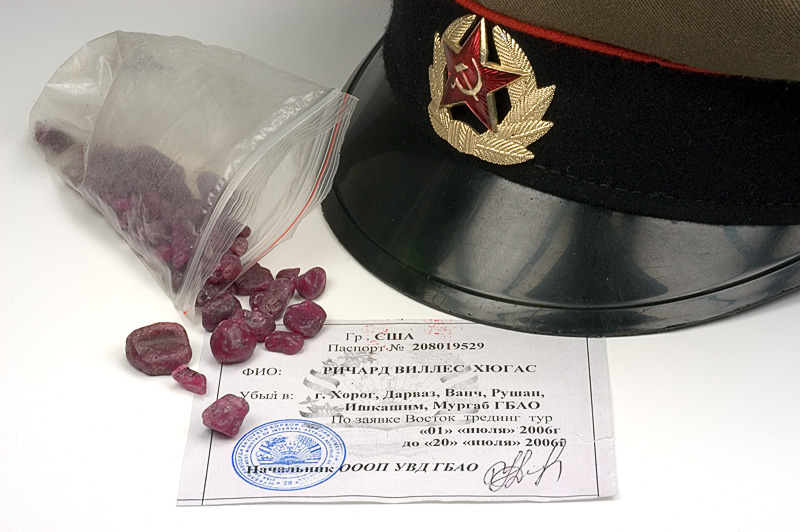

But how the Hun does one get there? First comes the visa. Like Russia and all other ex-Soviet republics, you need a letter-of-invitation (LOI). Which is asking a bit much of people who have never visited a place, but it does serve to keep the riffraff out. Such LOIs function simply as an entry tax. Wanna go to the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast (GBAO)? You'll need an entirely separate permit for that. Give yourself a minimum of one month to get fully stampified.

Tajikistan's Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast (GBAO), where both the ruby and spinel mines are found, is a restricted area, requiring a special permit, as shown above. Photo © Wimon Manorotkul/Pala International

Tajikistan's Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast (GBAO), where both the ruby and spinel mines are found, is a restricted area, requiring a special permit, as shown above. Photo © Wimon Manorotkul/Pala International

Now comes the real fun. Getting there. With but few exceptions, no matter where you might be, Dushanbe is out-of-reach. Air connections appear to be based on the poppy principle, existing mainly between Istanbul (Turkey), Kabul (Afghanistan), Almaty (Kazakhstan), and Russia. Frankly, we were a bit surprised there were no direct flights from Burma.

Wanna go by land? Sweet. The Taliban stand ready with roadside assistance. And the nearest other nation of note, Uzbekistan, maintains such sterling relations with the Tajiks that on our flight we met an Uzbek who preferred to travel to Dushanbe via Almaty, rather than brave the drive from Tashkent to the Tajik capital. Understand one thing: Dushanbe is miles from nowhere; somewhere is even further afield.

So what are the options? Two members of our party chose the "pansy path," crossing the Khyber Pass from Peshawar (Pakistan) to Kabul (Afghanistan), then a short air hop into Dushanbe. Those of us wanting a bit more adventure opted for the more circuitous Frankfurt-to-Almaty route, then on to Dushanbe via Tajikistan Airlines.

Happiness is…

Happiness is…

A flying carpet painting in a Dushanbe gallery. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Air Quirkistan

This is one carrier US airlines could learn from. Dump the expensive services. Tajikistan Airlines takes reservations only two weeks out. Customer inquiries? Our repeated e-mails elicited not even a single reply. On-time percentage? Arrive early – the printed schedule is just a rumor.

On the flight from Almaty, the entire rear third was filled with baggage. Boarding, a quick look round revealed cabin decor à la Cream, circa Disraeli Gears. All of it, ceilings, walls, seats, carpet, the whole shebong done up in psychedelic paisley patterns. Thanks god they weren't serving inebriants or things could have gotten quickly out-of-hand.

Hughes found himself wedged into anorexemy class. The metal tray table (yes, metal) had a notch ripped through where the peg was supposed to hold it against the seat back, leaving a jagged dagger just inches from his chest. Upon landing, he could only whisper "thanks god" that the seat in front was occupied by someone who understood his frantic slashing gestures, for even the slightest recline would have sawn him in two, a trick with no magician's happy ending.

Arriving at Dushanbe's airport, we taxied to the sight of a series of Soviet-era jets identical to ours, except for the various states of cannibalization. Comforting, we thought. Our plane had a full complement of gear. Of course, there's always the return flight…

Big Brother is still listening

Big Brother is still listening

A public phone in Dushanbe. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Satellites of Love

The good news is that Tajikistan is no longer part of the Soviet Union. The bad news is that nobody who matters really gives a damn. Following independence, Tajikistan simply incorporated all appendages of the previous regime into the new government. Including the KGB. Think about it. If you've invested close to a century building a worst-class bureaucracy, why let regime change rain on the charade? Understand, this ain't Spain. No plains, and even if it did rain, the KGB has a lock on the umbrella concession. This is particularly true in the GBAO where – whodda guessed it – the gems are found.

Okay, perhaps that's a bit harsh. There are other reasons for the restrictions. Some of them involve the mining of stuff used to build things that go boom boom, while others involve simple "strategery." As one Cold War veteran told me: "I've never been to Tajikistan, but back in the day, if anybody in Dushanbe ever dropped a penny, I'd have a photo of it before it hit the pavement."

Dushanbe is a Central Asian city with a European flair. Photo: Vincent Pardieu/fieldgemology.org

Dushanbe is a Central Asian city with a European flair. Photo: Vincent Pardieu/fieldgemology.org

Dushanbe

How does one describe a place? It often comes down to set and setting – mindset and surroundings. Those of us who had spent the previous month in Pakistan and Afghanistan discovered in Dushanbe a bygone world appearing before our eyes. Or half a world anyway – the female half. This was quite a set, amidst a lovely setting.

Dushanbe is nothing if not sublime, a beguiling blend of Central Asia and Russia – wide tree-lined boulevards where Islam walks in lazy tranquility with the more-permissive habits of a European city. We were left with a feeling of tolerance, such a rare commodity in today's polarized world.

Our arrival in Dushanbe was made all the more pleasant by Surat Toimastov, one of Tajikistan's top photographers, who has spent much of his life hiking, hunting and climbing throughout the Pamirs. In addition to Surat, we were joined by his son, Habib, and our driver, Valera. Together, they would shepard us across the remote eastern half of Tajikistan that is Gorno-Badakshan.

Dana Schorr, Richard Hughes and Vincent Pardieu examine the route to Badakhshan's ruby and spinel mines. Photo: Surat Toimastov

Dana Schorr, Richard Hughes and Vincent Pardieu examine the route to Badakhshan's ruby and spinel mines. Photo: Surat Toimastov

Pamir Highway

At the outset, let us say this: the road to the mines does not always lead to lands of milk and honey. During our three-week journey, we watched one travel companion retch out a car window (giardia?); days earlier another passed out on the floor of a yurt (malaria?), while a third rushed into the Murghab governor's mansion with a panic-stricken grimace that suggested breakfast was near detonation (liquid bomb?). Getting there is not always half the fun.

But perhaps we are getting ahead of ourselves. The journey to the mines was by road, with the initial destination being Khorog, capital of the GBAO. This gigantic province encompasses virtually the entire eastern half of the nation, including the famous Pamir mountain range. While making up 45% of the country's landmass, GBAO has just 3% of Tajikistan's population. Traveling through it, one is carried on a song, leaping from one magnificent stanza to another. It is certainly among the most photogenic places we have ever visited.

Guillaume "Guji" Soubiraa points out a drowned tank, reminder of the civil war that raged across Tajikistan for several years following independence from the Soviet Union. Photo: Vincent Pardieu/fieldgemology.org

Guillaume "Guji" Soubiraa points out a drowned tank, reminder of the civil war that raged across Tajikistan for several years following independence from the Soviet Union. Photo: Vincent Pardieu/fieldgemology.org

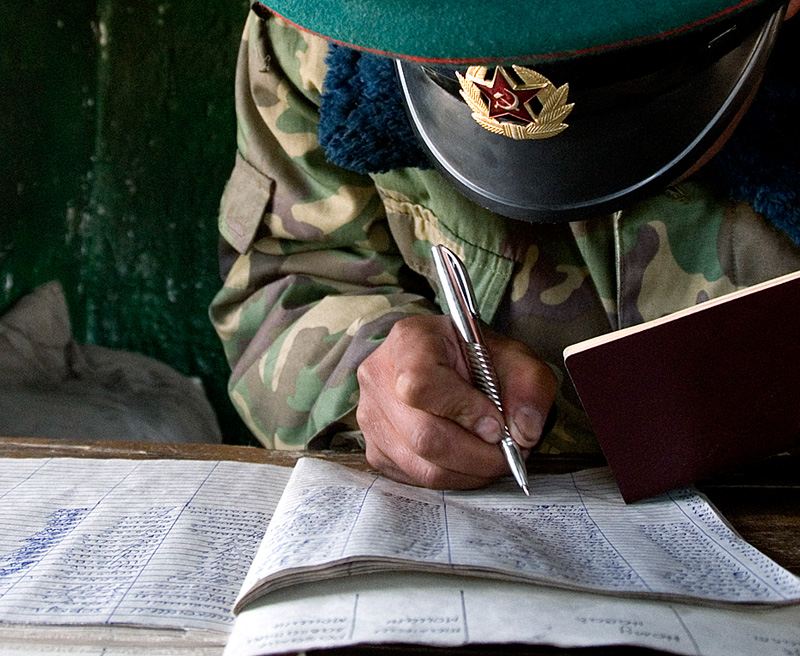

Exiting Dushanbe, one passes first through rolling hills which quickly turn to craggy outcrops and scalloped canyons, hinting at the higher elevations to come. The initial night found us bedding down at a wonderful homestay arranged by Surat, our introduction to traditional Tajiki life. Early on the second day, we entered the GBAO and its extensive series of Tajik KGB checkpoints. This area was the scene of the fiercest fighting during the civil war. All along the road reminders are seen of the conflict that raged just a few years before, with burned-out tanks and mine fields littering the roadsides.

Gorno-Badakhshan (GBAO) is a restricted area riddled with KGB and police checkpoints. Our final day's travel included no less than six such halts. Why the English sign? We know not, since only a handful of foreigners visit this region each year. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Gorno-Badakhshan (GBAO) is a restricted area riddled with KGB and police checkpoints. Our final day's travel included no less than six such halts. Why the English sign? We know not, since only a handful of foreigners visit this region each year. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Down and nearly out in Khorog

Following a two-day drive through ever-changing landscapes we arrived at Khorog, district headquarters of the GBAO. Our main task there was to finalize permits for visiting the spinel mines at Kuh-i-Lal, just two hours south, along with the ruby mines near Murghab, located in eastern Badakhshan, near the Chinese border.

Did we mention that Tajikistan has quite a bit of red tape? It took us five days in Khorog before the size of our "gift" became large enough to pry open the doors of Badakhshan official obstruction. And none too soon, for, while Khorog is a pleasant enough town, serious boredom had set in. Another day and we might have found ourselves swimming the river to join the Taliban. Anything for a bit of action…

Thankfully, we were spared that fate. With a brief letter of introduction from the Deputy Governor of Badakhshan asking for "cooperation," we left Khorog to explore the places each of us had traveled so far to see.

Russia and the former Soviet Republics may no longer be communist, but old habits die hard. KGB security checkpoints, such as that above in the Wakhan corridor, are a fixture across much of Tajikistan's Badakhshan region. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Russia and the former Soviet Republics may no longer be communist, but old habits die hard. KGB security checkpoints, such as that above in the Wakhan corridor, are a fixture across much of Tajikistan's Badakhshan region. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Kuh-i-Lal

Kuh-i-Lal's "balas ruby" (spinel) mines are among the oldest in the world, with the first recorded mention being that of the famous Central Asian polymath, al Biruni (973–1048):

The Badakhshani Ruby

Ruby mines are situated near the village of Warzqanj which is situated in the direction of Kharukhan while going from Badakhshan at three days' journey. It is a part of an emperor's domain, the capital of which is Shakasim, which is close to the mines producing this stone. The approach to the mines via this route is easier, and it passes between Shakkasmi and Shaknan. This is why the governor of Wakhan keeps the most precious jewels for himself, and precious jewels pass this way clandestinely. Jewels weighing beyond a certain size are prohibited from being carried outside the mine, and only stones weighing up to the sizes he has fixed or specified are permitted to be taken out.

It is said that the mine was located when there was an earthquake in the area and the mountain was cloven. Big rocks fell down and everything was destroyed. Rubies were disgorged in the process. Women thought the stone was something with which clothes could be dyed. They ground the stones, but no colour came out. Women showed the rubies to men and the matter was publicised. The king ordered the miners to locate the mine. When they found it they began to excavate it.

– al Biruni, 11th century

The story above is virtually identical to what local miners told us during our visit. They also informed us that in 1970, Ms. Mira Alekseyevna Bubnova of the A. Donish Institute of History, Archaeology and Ethnography (Tajik Academy of Sciences) found evidence the mine was operating as early as the seventh century AD.

Stories of the Kuh-i-Lal mines are legendary, and are detailed in Hughes (1994, The rubies and spinels of Afghanistan: A brief history). Kuh-i-Lal is thought to have produced many of the most famous spinels in the world, including the Black Prince's Ruby and the Timur Ruby. But because similar stones from these mines have not been documented in the modern era, the question of whether these famous stones came from Kuh-i-Lal, or perhaps another locality such as Mogok, Burma, is still debated in gemological circles (see 'Balas Rubies: Myth or Reality' at the end of this article).

A miner at Kuh-i-Lal holds up a piece of impure spinel. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

A miner at Kuh-i-Lal holds up a piece of impure spinel. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

The Kuh-i-Lal spinel mines are almost halfway between Khorog and Ishkashim, high on a cliff overlooking the beautiful village of the same name. This is directly next to the Panj (Pamir) River, which forms the natural border between Tajikistan and Afghanistan. From the mines themselves the views into Afghanistan and the Hindu Kush range are stunning.

Our first visit to Kuh-i-Lal was difficult, as we had not yet obtained formal permission. As a result, we were only permitted to enter the ancient galleries, which are no longer being actively worked.

Richard Hughes at the storied Kuh-i-Lal spinel mines, which lie high on a mountain above the Panj (Pamir) River, which separates Afghanistan (left) from Tajikistan (right). Photo: Dana Schorr

Richard Hughes at the storied Kuh-i-Lal spinel mines, which lie high on a mountain above the Panj (Pamir) River, which separates Afghanistan (left) from Tajikistan (right). Photo: Dana Schorr

The historic mines are located at 37°10'71"N, 71°28'47"E; elev. 2900 m (9514 ft). They were reached after a stiff 45-minute climb up a goat track. Donning hard hats and head lamps, we entered the mines. The tunnels quickly narrowed, twisting and turning in what was obviously an attempt to follow gem-bearing veins. We soon became lost in a mountain honeycombed with passages, some so narrow that access was only by crawling on hands and knees or slithering like snakes on our bellies. And yet in places the tunnels opened up into substantial rooms as much as 20 m in length and 8 m in height, suggesting the removal of rich pockets of gems.

Dana Schorr inside one of the ancient galleries at the storied Kuh-i-Lal spinel mines. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Dana Schorr inside one of the ancient galleries at the storied Kuh-i-Lal spinel mines. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Inspecting the tunnel walls, we did not locate any fine crystals in the marble matrix, not surprising since these tunnels were long ago abandoned, but we were shown two tiny pinkish crystal fragments. Sadly, due to bureaucratic restrictions we were unable to bring these home for further study.

Miners informed us that approximately 10,000 cubic meters of rock had been taken out of these ancient galleries over the ages, creating an incredible catacomb of meandering passages. It was clear that without a guide one could quickly become lost. At Kuh-i-Lal, there are said to be nine major tunnels, but only two currently in operation. One of these penetrates 800 m into the mountain, while the other is said to be 500 m deep.

A miner with Vincent Pardieu inside the ancient galleries at Kuh-i-Lal spinel mines. Photo: Dana Schorr

A miner with Vincent Pardieu inside the ancient galleries at Kuh-i-Lal spinel mines. Photo: Dana Schorr

Inquiring after production, miners told us that all stones were sent to Dushanbe, to the state-run Gubjemast Company, which had a monopoly over gem production in Tajikistan. In terms of color, we were told that over the past three years, spinels from the current workings were approximately 50% red and 50% pink. But when we examined production back in Dushanbe, we were not shown even a single low-quality red spinel. In Dushanbe, we were given various stories, everything from 10–50% red. Later, when we were actually afforded an opportunity to view stones at Gubjemast, we were told that red spinels are found just once every ten years. Perhaps red spinels are found, but don't know the way to Dushanbe?

Rough spinel from Kuh-i-Lal. Photo: Vincent Pardieu/fieldgemology.org

Rough spinel from Kuh-i-Lal. Photo: Vincent Pardieu/fieldgemology.org

The fact is that, while we know companies in Bangkok that sell Pamir spinel, they've never shown us a red stone. Instead, these firms sell pink and purplish stones, similar to those we saw at the mines and at the Gubjemast mining office in Dushanbe. Thus the mystery continues.

In addition to spinel, clinohumite is also recovered at Kuh-i-Lal. Cut stones can be lovely and are locally termed "sunflower stone." Such stones have also been mentioned in the ancient accounts of the mines. Colorless forsterite (not pictured) is also found. Photo: Vincent Pardieu/fieldgemology.org

In addition to spinel, clinohumite is also recovered at Kuh-i-Lal. Cut stones can be lovely and are locally termed "sunflower stone." Such stones have also been mentioned in the ancient accounts of the mines. Colorless forsterite (not pictured) is also found. Photo: Vincent Pardieu/fieldgemology.org

This 6.76-ct clinohumite is a fine example of the "sunflower stone" from Kuh-i-Lal. Stone courtesy of Pala International; Photo: Wimon Manorotkul/Pala International

This 6.76-ct clinohumite is a fine example of the "sunflower stone" from Kuh-i-Lal. Stone courtesy of Pala International; Photo: Wimon Manorotkul/Pala International

Following our visit to the ruby mines, we again returned to Kuh-i-Lal, but were once more thwarted in our attempts to enter the modern tunnels. While we did have a letter of authorization from the Deputy Governor of Badakhshan, we were told we would also need a KGB permit. On the farm, all animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others…

Welcome to Yurtistan

Welcome to Yurtistan

A solitary yurt stands on the plain south of Murghab, in Tajikistan's far eastern region. Photo: Vincent Pardieu/fieldgemology.org

Welcome to Yurtistan

Having visited Kuh-i-Lal, we next traveled east along the Pamir Highway, passing through ever-more spectacular mountain landscapes. Several hours of driving brought us to a pass. Crossing it, we dropped into an arid high-altitude region that, excepting the the grasslands along the valley floors, resembled nothing so much as the moon. Periodically the desolation was broken by small herds of yaks and the occasional yurt. This region was the home not of Tajiks (who are ethnically related to the Persians), but to Kyrgyz, a people thought to have originated from Siberia, but later pushed south by invading Mongols. We enjoyed several meals and one night in "Yurtistan." Our time in these comfortable dwellings amidst these hospitable people was an experience none of us will ever forget.

Vincent bin Laden enjoying a bit of downtime in Yurtistan. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Vincent bin Laden enjoying a bit of downtime in Yurtistan. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Murghab – Fly me to the moon

Murghab was reached following a ten-hour drive from Khorog. This regional capital is located on a swampy plain at 3576 m (11,732 ft). Its population of about 6500 people makes Murghab the largest outpost in sparsely-settled eastern Badakhshan.

Great things are planned for Murghab. Located near the border of western China's Xinjiang province, with the recent completion of a new bridge and road, it is now hoped it will become the eastern gateway to the Pamirs. Indeed, we were told that the Aga Khan Foundation, which has performed marvelous humanitarian work in Badakhshan, once brought in a European planning expert to see about sprucing the place up for the planned tourist onslaught. Taking a look at Murghab, he said that, regrettably, he would be unable to help, for, while he had over thirty years' experience in city planning, none of it was on the moon.

The lunar scenery surrounding Tajikistan's ruby mines is just beyond spectacular. Click on the photo for a larger image. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

The lunar scenery surrounding Tajikistan's ruby mines is just beyond spectacular. Click on the photo for a larger image. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Upon our arrival we visited the local governor's office and found a warm welcome, with the red carpet rolled out. Unlike at Kuh-i-Lal, where suspicion was the watchword, officials in Murghab were most helpful. Indeed, the following day we left for the mines with an official provided by the local governor, along with M. Ramsy, the mine director. The one-and-a-half hour drive northeast was through a wonderful semi-desert landscape.

Vincent Pardieu and Richard Hughes with the Snezhny ruby mines in the distance. Photo: Guillaume Soubiraa

Vincent Pardieu and Richard Hughes with the Snezhny ruby mines in the distance. Photo: Guillaume Soubiraa

Discovered in 1979, a handful of stones reached foreign markets in the 1990s (Bank, 1990). We saw our first Tajik rubies during the first half of 2006, when stones reputed to be from this source suddenly reached the international markets through dealers from Tashkent, Peshawar, Bangkok, Hong Kong and Dubai (inclusion photos of some of these rubies can be found at Pardieu, 2006).

Richard Hughes showing his book Ruby & Sapphire to a group of miners at Snezhny. Photo: Dana Schorr

Richard Hughes showing his book Ruby & Sapphire to a group of miners at Snezhny. Photo: Dana Schorr

Initially, some traders represented these attractive pink-to-vivid-red rubies as being from a new mine in Burma, but others suggested they were actually from the Murghab region in eastern Badakhshan, near the Chinese border. Indeed, their inclusions and color closely matched published descriptions of Tajik rubies (Smith, 1998). Their arrival convinced us that a visit to Tajikistan was in order.

A miner rests during lunch at Tajikistan's ruby mines near the Chinese border. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

A miner rests during lunch at Tajikistan's ruby mines near the Chinese border. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Tajikistan's ruby mines are located in a place called Kukurt. The Kukurt (a.k.a. Turakulominsky) ruby deposit contains a number of outcrops, including Snezhny, Trika, Nizhny, and Gloria). We visited the site at Snezhny (a.k.a. Snijnie, Snagnyi or Snezhnoye) ( 38°15'72"N, 74°23'37"E, elev. 4090 m; 13,418 ft). Snezhny is a Russian word for "snowy," a not-inappropriate name since it snowed a bit on the day of our visit. In July.

The Snezhny mining camp, consisting of about 15 rustic houses, lies about 42 km by road east-northeast of Murghab on a gentle slope at the end of an arid high-altitude valley. As one can see, the scenery surrounding the mines is just beyond spectacular.

Lunar landscape near the Snezhny ruby mines in eastern Tajikistan. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Lunar landscape near the Snezhny ruby mines in eastern Tajikistan. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

The deposit was discovered in 1979 by Russian geologists. According to the miners, the present location has been worked since 2003. From the 1970s to 2003 another location at Kirkut, some 10 km to the north was worked, but due to time constraints we were unable to visit that area. It seems that the Snezhny and Kirkut mines represent a ruby-bearing marble zone measuring some 50 km by 200 km, extending all the way to the Chinese border.

A bulldozer works the vein, while miners look on from above at the Snezhny ruby mines in eastern Badakhshan. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

A bulldozer works the vein, while miners look on from above at the Snezhny ruby mines in eastern Badakhshan. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

At the time of our visit, mining consisted of digging trenches in places where the ruby-rich marble layers were exposed or close to the surface. This is not unlike the Jegdalek ruby deposit in Afghanistan. To our surprise, we witnessed no alluvial or eluvial mining. When asked about this, miners told us that, while they had prospected the valley floor below the marble outcrops, lack of water made such work difficult. This we could understand. Beyond snow melt, water appeared to be in short supply throughout the Murghab region.

Flecks of red ruby and green fuchsite mica are seen in the marble matrix at the Snezhny ruby mines in eastern Badakhshan. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Flecks of red ruby and green fuchsite mica are seen in the marble matrix at the Snezhny ruby mines in eastern Badakhshan. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Close examination of the walls of the mining trenches revealed bits of ruby and green fuchsite mica peeking out from the marble, which was found in a gneiss country rock. In discussions with workers and geologists at the mine, we were told that the closer the rubies are to the gneiss, the richer is the rubies' color.

Central Asia is a beguiling mixture of cultures, a true crossroads of humanity. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Central Asia is a beguiling mixture of cultures, a true crossroads of humanity. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

At the time of our visit, roughly ten miners were working. Dynamite was used to break up the country rock in order to reach the ruby-rich zones, with a bulldozer later brought in to further expose the veins. Ruby is then extracted from the marble by hand, a laborious process. Production is then sent to the Gubjemast office in Dushanbe. Miners told us that the largest fine crystal found was around 200 grams.

Three lots of "ruby" reputed to be from Tajikistan and obtained from a source in Tashkent, Uzbekistan. While the lower two are indeed ruby, the top lot proved to be dark red garnet. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul/Pala International

Three lots of "ruby" reputed to be from Tajikistan and obtained from a source in Tashkent, Uzbekistan. While the lower two are indeed ruby, the top lot proved to be dark red garnet. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul/Pala International

On the short walk to the mines, garnet and kyanite were seen in the brief periods where our eyes were not focused on the stunning beauty of the surrounding landscape. In addition, at Rangkul next to Kukurt Lake near Murghab are found topaz, amethyst, polychrome tourmaline, amazonite, scapolite, schorl and jeremejevite.

During Soviet times, many Russian geologists worked in the Murghab area and the remains of a large geologist's base camp can be seen on the edge of town. We were told that numerous surveys were undertaken in pegmatite-rich areas. Both Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan were the source of major uranium and rare-metal deposits. This is one possible reason why, to this day, Tajikistan's gemstone mines are still seen as "strategic areas."

Eastern Badakhshan is one of the last strongholds of the Marco Polo sheep. This photo was taken near Jarty Gumbez. At that camp, hunting is strictly controlled, with a cull of just 50 rams per year, allowing the preservation of this endangered species. Only about 10,000 of these sheep remain. Trophy hunters spend $25,000 and up to bag this largest of all sheep. Photo: Surat Toimastov

Eastern Badakhshan is one of the last strongholds of the Marco Polo sheep. This photo was taken near Jarty Gumbez. At that camp, hunting is strictly controlled, with a cull of just 50 rams per year, allowing the preservation of this endangered species. Only about 10,000 of these sheep remain. Trophy hunters spend $25,000 and up to bag this largest of all sheep. Photo: Surat Toimastov

Following our visit to the Murghab area, we continued our trip south to a hunter's camp at Jarty Gumbez, then through the Tajik portion of the Wakhan corridor to Ishkashim. From there, after another aborted stab at Kuh-i-Lal, it was back to Dushanbe, via an Afghan-border hugging route dotted with KGB checkpoints.

A handful of sapphire and garnet crystals offered to us in the Wakhan Corridor, including one on matrix. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

A handful of sapphire and garnet crystals offered to us in the Wakhan Corridor, including one on matrix. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Downtempo in Dushanbe: A visit to Gubjemast

Have we mentioned Tajikistan's bureaucracy? In Tajikistan, gem production and the gem trade are strictly regulated. The precious stone business as it exists in most other countries is, in Tajikistan, illegal. Both the ruby and spinel mines are considered strategic resources. Thus even the most mundane procedure becomes a knot of Gordian proportions, one which even the tiniest of Persian fingers cannot unravel.

During our visits to the ruby and spinel mines, we learned that gemstone mining in Tajikistan is controlled by the Gubjemast company (meaning 'amethyst' in Tajik), headquartered in Dushanbe. Whenever we would inquire about viewing or purchasing samples, the answer would always be the same: "You must contact Gubjemast." Thus our first order of business upon returning to Dushanbe was to "contact Gubjemast."

Boxes of rough ruby from the Snezhny mines are unsealed at the Gubjemast office in Dushanbe. Photo © Vincent Pardieu/fieldgemology.org

Boxes of rough ruby from the Snezhny mines are unsealed at the Gubjemast office in Dushanbe. Photo © Vincent Pardieu/fieldgemology.org

But locating Gubjemast proved almost as daunting as gaining entry to the mines. This was clearly not a high-profile operation. After thirty minutes of hunting for an office that was smack-dabski in front of where the taxi dropped us, we finally ascended the stairs of a building that makes "nondescript" look like a Vegas casino. Gubjemast was clearly a company that was not – how shall we say this – "customer focused."

Our visit did not begin on an auspicious note. As we nudged open the door, a gentleman stepped out. We asked if this was the Gubjemast company and he answered in the affirmative. Indeed, he was the Managing Director, at least until the previous day when, after more than twenty years of service, he was sacked. Seems that Tajikistan's President preferred someone who was a party loyalist, albeit one with little experience in either minerals or gems.

We quickly explained our mission and the gentleman graciously invited us into his office, patiently answering all manner of questions regarding the mines and Tajikistan's gem business. But as he was now on the way out, he could not show us any samples. For this we would have to ascend yet another rung on Tajikistan's ladder of leadership.

Rough Tajik ruby in the Gubjemast office in Dushanbe. Photo: Vincent Pardieu/fieldgemology.org

Rough Tajik ruby in the Gubjemast office in Dushanbe. Photo: Vincent Pardieu/fieldgemology.org

Did we mention that bureaucracy is serious business in Tajikistan? In order to even view a single stone, we had to organize a meeting with the Deputy Minister of Industry. Through the good efforts of two of our local contacts, this was accomplished. Taking two hours of time of the number two man at the Ministry of Industry just to see some small gem lots might seem a bit bizarre, but – let's just come right out and say it – it was totally bizarre. Akin to having to meet the Postmaster General to purchase a few stamps. Thankfully, the Deputy Minister proved to be most cordial and, in addition to arranging permission for us to view samples, gave his blessing so we could examine documents regarding the mines.

Rough spinel at Gubjemast's Dushanbe office. Photo: Vincent Pardieu/fieldgemology.org

Rough spinel at Gubjemast's Dushanbe office. Photo: Vincent Pardieu/fieldgemology.org

Did we mention that bureaucracy is serious business in Tajikistan? Despite support from the Ministry of Industry, we discovered that buying gemstones in Tajikistan is not an easy task, at least if you try to do it legally. During our second visit to Gubjemast we attempted to buy rough samples for scientific research, but the process proved to be as complex the rest of the journey. The regulations are something like this:

- Foreigners are only allowed to purchase gems at special sales.

- Such special sales take place only in December.

Since it was July, and since we had misplaced our LOI from the Minister of Corruption, we were facing some serious downtime in Dushanbe.

Vincent Pardieu talking turkey in Gubjemast's Dushanbe office. Photo: Guillaume Soubiraa

Vincent Pardieu talking turkey in Gubjemast's Dushanbe office. Photo: Guillaume Soubiraa

Seeing the obvious disappointment on our faces, we were then told it might be possible to buy just a few samples during our visit.

GOAL!

Hopes now raised to the stratosphere, we confidently selected ten small pieces of rough worth perhaps $20 and requested a price. After a bit of hushed talk, the answer came back that these would lighten our wallets by $200. Huh? Perhaps an extra zero had mistakenly found its way into the equation?

No. $200.

Okay, an obvious rip-off, but for the sake of science and the brotherhood of man, we agreed.

Hmmm… Following further whispered discussions, we were then informed that the paperwork necessary to export the gems would cost us $600. And the export process would take a month. Did we mention that paperwork was important in Tajikistan?

This called for a bit of hushed discussions of our own. Hmmm… no. Put away the shears. These sheep would be leaving no wool behind in Dushanbe. No goal.

Jerry Springer moment

It is clear that some serious reconfiguration in the bureaucratic arena needs to be done before Tajikistan can develop a strong gem industry. Remarkably, the easiest legal way to purchase Tajik rough is to invest in the mining operations with Gubjemast. Companies from China, Ukraine and Bishkek (Kyrgyzstan) are said to operate under this type of arrangement. But for most, a serious investment in a remote mine is out of the question. Thus, for the time being, foreign dealers will simply purchase stones abroad. You see, most Tajik gemstones do not know the way to Dushanbe.

Photomaniacs

Photomaniacs

Richard Hughes, Guillaume Soubiraa and Surat Toimastov gettin' some along the Pamir Highway. Photo © Vincent Pardieu/fieldgemology.org

Bringin' it on home

Like I explained to you before, I'm a people worshiper. I think people should worship people. I really do.

I went out looking for God the other day and I couldn't pin him. So I figured if I couldn't find him, I'd look for his stash, his Great Lake of Love that holds the whole world in gear. And when I finally found it, I had the great pleasure of finding that people were the guardians of it. Dig that.

So with my two-times-two is four, I figured that, if people were guarding the stash of love known as God, then when people swing in beauty, they become little gods and goddesses. Lord Buckley, Religion

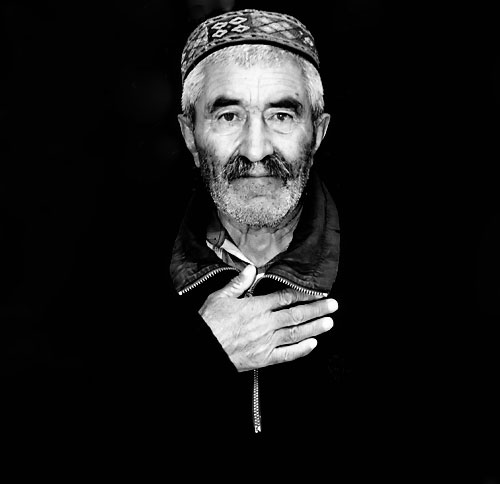

Let us clue you in on a secret. The most important reason to visit far-flung locales has absolutely nothing to do with stones. Watch the world via the evening news and you're bound to come away with a negative impression. Everyday kindness rarely makes the cut. And yet we have experienced it no matter where on this earth our feet have landed.

Witness the photograph below. As we were traveling through Badakhshan, our party paused on the roadside. This Tajik girl appeared, armed with a bottle of fresh fermented milk. Approaching, she smiled shyly, extended it to us and then walked away. Could this be a plot? The Afghan border was less than a kilometer away and Chitral (Pakistan), where Osama was thought to be hiding, just a turban's throw from that. Tossing caution aside, we drank deeply, and survived.

Got milk. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Got milk. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Days later, after a tough descent from Kuh-i-Lal, two Wakhi girls skipped past carrying an urn. Stopping, they offered us generous helpings of their fresh goat cheese. In one of the poorest regions of the world, these goddesses thought nothing of sharing what they had with visitors from abroad. When was the last time we treated foreigners with similar grace and decency?

Hate and distrust are easy at a distance, but more difficult up close, when people are not abstractions, but something real, something you can see, something you can feel, something you can touch.

Why travel? Let us answer that riddle with a picture. The gem is a piece of ordinary red glass, worth perhaps a dollar. But gaze into this Kyrgyz' girl's eyes and you will find discover priceless treasure. Gems are accessories. Life and living is about people. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Why travel? Let us answer that riddle with a picture. The gem is a piece of ordinary red glass, worth perhaps a dollar. But gaze into this Kyrgyz' girl's eyes and you will find discover priceless treasure. Gems are accessories. Life and living is about people. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Moonwalking

All who walk this earth are born under the same moon. Our shared humanity is far greater than differences in language, culture or religion. This lesson is the true mother lode of travel, more precious than any stone we might bring home. Grasp this simple concept and wherever your feet touch down, it will always be a land of milk and honey.

And what of those New York subways? Despite their dangerous reputation, they too contain unexplored mysteries. Indeed, when Manhattan's tunnels were excavated in the 19th century, gem garnets were found.

So fear not. Go forth and explore this magical planet. Seek knowledge, even unto Manhattan!

|

Appendix: Balas Rubies – Myth or Reality? by R.W. Hughes From the historical record, it is clear that the Badakhshan mines were of great importance during the period from 1000–1900 AD. While some might argue otherwise, it is safe to say that, based on the numerous historical accounts, the Badakhshan mines were the source of many of the finest early red spinels in gem collections around the world, such as those in Iran's Bank Markazi, Istanbul's Topkapi, Russia's Kremlin, and England's Tower of London. Unfortunately, such mines are largely overlooked, with some gemologists even suggesting that the only historic source of big red spinels is Burma. This is not based upon any particular evidence, such as comprehensive inclusion studies, for these studies do not exist, either for Burma or Sri Lankan spinels, nor for those from Badakhshan. Instead, it simply rests upon the belief that what is today, has always been. But history is replete with examples that demonstrate otherwise. Witness the famous Kashmir sapphire mines, where within a brief blink-of-the-eye period (1881–1887), the "old mine" produced such a quantity of fine stones that they achieved a reputation second to none. So fine was their quality that, today, they remain the standard against which all other sapphires are measured. And yet in the more than 120 years that have since passed, few stones of the original quality have been unearthed. Utterly incredible, but absolutely true. Would any gemologist argue that the famous Kashmir sapphires came from another locale because the current mine does not produce stones of the original quality? Ditto Golconda diamonds. While evidence for the existence of the Badakhshan mines is not direct, it is substantial. As proof, we have the name balas ruby, which is apparently derived from an ancient word for Badakhshan, we have numerous detailed accounts of the mining, we have spinels with Arabic inscriptions and we have historical names, such as the Timur ruby. Circumstantial? Indeed. But if circumstantial evidence was of no value, the world's jails would be empty.

In summing up the evidence for a Badakhshan origin for these stones, we will close with this from a Christie's catalog on Indian jewelry: The habit of inscribing objects and gems in order to personalize them was a Timurid fashion. The Timurids, a dynasty founded by Timur (Tamerlane) ruled over Afghanistan, large parts of Iran and Central Asia from the late 14th to the late 15th centuries. It was to the Timurids that the Mughals ultimately owed many debts in the development of their particular imperial style. A very large red spinel, known as the "Timur Ruby" now in the British Crown Jewels [actually in Queen Elizabeth's private collection], was once in the possession of Jahangir. The stone was presumably once inscribed with Tamerlane's name and thus may have set a precedence for the habit of inscribing precious stones. Several objects made of semi-precious stones and inscribed with his name are known. In the case of gemstones, every new royal owner had his own inscription added as a mark of ownership, often having the old erradicated. One of the spinels in the present necklace is inscribed with the name of Jahangir, along with the title sahib-i-qiran-i sani ("Second Lord of the Conjunction") referring to Shah Jahan, and another later owner, suggesting too that these stones were handed down as prized possessions. – Christie's, 1999, Important Indian Jewellery

|

References & further reading

- Aziz, A. (1942) The Imperial Treasury of the Indian Mughuls. Lahore, privately published, reprinted 1972 by Idarah-I Adabiyat-I Delli, Delhi, 572 pp.; RWHL*.

- Bala Krishnan, U.R. (2001) Jewels of the Nizams. New Delhi, Dept. of Culture, Govt. of India in association with India Book House, Mumbai, 240 pp.; RWHL*.

- Ball, V. (1893) A description of two large spinel rubies, with Persian characters engraved upon them. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 381-401, reprinted in Gemological Digest, 1990, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 57-68; RWHL*.

- Bancroft, P. (1989) Record Russian spinels. Lapidary Journal, Vol. 43, No. 4, p. 41; RWHL.

- Bancroft, P. (1990) Spectacular spinel. Lapidary Journal, Vol. 43, No. 11, February, p. 25; RWHL.

- Bank, H. and Henn, U. (1990) New sources for tourmaline, emerald, ruby, and spinel. ICA Gazette, April, p. 7; RWHL.

- Barthoux, J. (1933) Lapis-lazuli et rubis balais des cipolins afghans. Comptes Rendus de l'Academie des Sciences de France, Vol. 196, 10 avril, pp. 1131–1134; RWHL.

- Barot, N.R. and Kremkow, C. (1991) 1991 ICA world gemstone mining report. ICA Gazette, August, pp. 12–15; RWHL.

- Beach, M.C. and Koch, E. (1997) King of the World: The Padshahnama, an Imperial Mughal Manuscript from the Royal Library, Windsor Castle. London, Azimuth Editions, 248 pp.; not seen.

- Bernard, J.H. and Hyrsl, J. (2004) Minerals and Their Localities. Prague, Granit SRO, 808 pp.; not seen.

- Beruni, M.i.A., al- (1989) The Book Most Comprehensive in Knowledge on Precious Stones: al-Beruni's Book on Mineralogy [Kitab al-jamahir fi marifat al-jawahir]. One Hundred Great Books of Islamic Civilization, Natural Sciences No. 66, Islamabad, Pakistan Hijra Council, edited by Hakim Mohammad Said, 355 pp.; RWHL*.

- Blair, C., Bury, S. et al. (1998) The Crown Jewels: The History of the Coronation Regalia in the Jewel House of the Tower of London. London, The Stationery Office, 2 Vols., 812, 630 pp.; seen*.

- Bowersox, G.W. and Chamberlin, B. (1995) Gemstones of Afghanistan. Tucson, AZ, Geoscience Press, xx, 172 pp.

- Bowersox, G. (2005) July–August, 2005 Hindu Kush/Pamir Mountains Expedition. Gems-afghan.com.

- Burnes, A. (1835) Travels into Bokhara. London, 2 Vols., see pp. 177–178; not seen.

- Christie's (1999) Important Indian Jewels. London, Christie's, 6 October 1999, 96 pp.; RWHL.

- Fersman, A.E. (1954–61) Ocherki Po Istorii Kamnya [Gems of Russia]. Moskva, Izdatelstvo Akademii Nauk SSSR, 2 Vols., In Russian, 370, 370 pp.; not seen*.

- Hauser, M. (2004) The Pamirs – 1:500 000: A Tourist Map of Gorno Badakhshan-Tajikistan and Background Information on the Region. Hinteregg, Switzerland, Pamir Archive, RWHL*.

- Henn, U., Bank, H. et al. (1990) Rubine aus dem Pamir-Gebirge, UdSSR. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Gemmologischen Gesellschaft, Vol. 39, No. 4, pp. 201–205; RWHL*.

- Henn, U. and Hyrsl, J. (2001) Gem-quality clinohumite from Tajikistan and the Taymyr region, northern Siberia. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 27, No. 6, pp. 335–339; RWHL.

- Hughes, R.W. (1994) The rubies and spinels of Afghanistan: A brief history. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 24, No. 4, October, pp. 256–267; RWHL*.

- Hughes, R.W. (1997) Ruby & Sapphire. Boulder, CO, RWH Publishing, 512 pp.; RWHL*.

- Kammerling, R.C., Scarratt, K. et al. (1994) Myanmar and its gems—An update. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 24, No. 1, pp. 3–40; RWHL*.

- Keene, M. and Kaoukji, S. (2001) Treasury of the World: Jeweled Arts of India in the Age of the Mughals. New York, Thames & Hudson, 160 pp.; RWHL*.

- Kievlenko, E.Y. (2003) Geology of Gems. Trans. by Soregaroli, A., Vancouver, Ocean Pictures Ltd., 432 pp. + xxxii; RWHL*.

- Koivula, J.I. and Kammerling, R.C. (1989) Examination of a gem spinel crystal from the Pamir Mountains. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Gemmologischen Gesellschaft, Vol. 38, No. 2/3, pp. 85–88; RWHL.

- Kammerling, R.C., Koivula, J.I. et al. (1995) Gem News: Large spinel from Tajikistan. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 31, No. 3, Fall, p. 212; RWHL.

- Laurs, B.M. and Quinn, E.P. (2004) Clinohumite from the Pamir Mountains, Tajikistan. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 40, No. 4, Winter, pp. 337–338; RWHL.

- Markham, C.R. (1859) Narrative of the Embassy of Ruy Gonzalez de Clavijo to the Court of Timour, at Samarcand, A.D. 1403–6. London, Hakluyt Society, Burt Franklin reprint, 200 pp.; see pp. 163; RWHL.

- Mayhew, B., Clammer, P. et al. (2004) Central Asia. Footscray, Australia, Lonely Planet Publications, 3rd Edition, 512 pp.; RWHL*.

- Meen, V.B. and Tushingham, A.D. (1968) The Crown Jewels of Iran. Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 159 pp.

- Pardieu, V. (2006) Rubies from Tajikistan. Asian Institute of Gemological Sciences.

- Pardieu, V. and Soubiraa, G. (2006) From Kashmir to Pamir: An update on Ruby, Emerald and Spinel mining in Central Asia. Tajikistan: Gems from the Pamirs. fieldgemology.org.

- Peretyazhko, L.S., Zagorsky, V.E. et al. (1999) Miarolitic pegmatites of the Kurkurt Group of gemstone deposits, central Pamirs: The evolution of physical conditions in the Amazonitovaya vein. Geochemistry International, Vol. 37, No. 2, pp. 108–127; not seen.

- Phillips (1994) A Singular Private Collection of Mughal and Later Indian Jewellery and Other Properties. Geneva, Phillips, Tuesday, 17 May, 51 pp.; RWHL.

- Prior, K. and Adamson, J. (2000) Maharajas' Jewels. New York, Vendome Press, 205 pp.; RWHL*.

- Rossovsky, L.N. and Konovalenko, S.I. (1980) [Gemstones in the pegmatites of Hindu Kush, southern Pamirs and western Himalayas] in Russian. In Gem Minerals (Proceedings of the XI General Meeting of IMA, Novosibirsk), ed. by V.V. Bukanov et al., pp. 52–62; not seen.

- Samsonov, J.P. and Turingue, A.P. (1985) Gems of the USSR. Mockba, seen.

- Smith, C.P. (1998) Rubies and pink sapphires from the Pamir Range in Tajikistan, former USSR. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 26, No. 2, pp. 103–109; RWHL.

- Stronge, S. (1996) The myth of the Timur ruby. Jewellery Studies, Vol. 7, pp. 5–12; RWHL*

- USSR Diamond Fund (1972) USSR Diamond Fund Exhibition. Moscow, 54 pp. + 66 color plates; RWHL*.

- Wood, J. (1841) A Journey to the Source of River Oxus. London, John Murray, 2nd ed., 1872, reprinted 1976, Oxford Univ. Press, 280 pp.; RWHL.

- Yevdokimov, D. (1991) A ruby from Badakhshan. Soviet Soldier, No. 12, Dec., pp. 71–73; RWHL.

- Younghusband, G. and Davenport, C. (1919) The Crown Jewels of England. London, Cassell and Co., Ltd., 84 pp.; RWHL.

- Yule, H. and Burnell, A.C. (1903) Hobson-Jobson. London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1st ed., 1886; 2nd ed. 1903 by William Crooke, reprinted 1995, AES, New Delhi, 1021 pp. (see Balass, p. 52); RWHL.

- Yule, H. (1872) Papers connected with the upper Oxus regions. Journal of the Royal Geographical Society, Vol. 42, pp. 438–513, 2 maps; RWHL.

- Yule, H. and Cordier, H. (1920) The Book of Ser Marco Polo. London, Murray, 3 Vols., 3rd edition, 1929, 462, 662, 161 pp.; RWHL*.

- Zolotarev, A.A., Dzhuraev, Z.T. et al. (2000) Jeremejevite from pegmatite veins in the Eastern Pamirs [in Russian with English abstract]. Proceedings of the Russian Mineralogical Society, No. 2, pp. 64–70; not seen.

Reference key

RWHL = References in the personal library of Richard W. Hughes

seen = References seen by RWH

not seen = references not seen by RWH, but possibly of interest

* = Denotes works of particular merit

A Wakhi man gives the traditional Tajik greeting. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

A Wakhi man gives the traditional Tajik greeting. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all those who assisted their journey. First, the following individuals deserve special mention:

We extend gracious thanks to our guide, Surat Toimastov, whose knowledge of and love for Badakhshan are truly second-to-none. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

We extend gracious thanks to our guide, Surat Toimastov, whose knowledge of and love for Badakhshan are truly second-to-none. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

We extend gracious thanks to Surat's son, Habib ('now I've been to Jarty Gumbez') Toimastov. Habib was a wonderful traveling companion, always quick with a smile and never complaining. Photo: Surat Toimastov

We extend gracious thanks to Surat's son, Habib ('now I've been to Jarty Gumbez') Toimastov. Habib was a wonderful traveling companion, always quick with a smile and never complaining. Photo: Surat Toimastov

We extend gracious thanks to our driver, Valera Yakubov, who kept us on the proper path and constantly made sure our cups had at least a "leetle leetle." Photo: Richard W. Hughes

We extend gracious thanks to our driver, Valera Yakubov, who kept us on the proper path and constantly made sure our cups had at least a "leetle leetle." Photo: Richard W. Hughes

We extend gracious thanks to the lovely Nargiz Sahibova, who was our guide in Dushanbe, showing us the sites and using her contacts to help with important meetings. Good luck with your studies in China. Photo: Dana Schorr

We extend gracious thanks to the lovely Nargiz Sahibova, who was our guide in Dushanbe, showing us the sites and using her contacts to help with important meetings. Good luck with your studies in China. Photo: Dana Schorr

We also extend our gratitude to Swiss cartographer, Markus Hauser, whose map of Gorno-Badakhshan was our constant companion, and who introduced us to Surat. We thank Gulov Mamadali, Deputy Minister of Industry, who arranged permission for us to visit Gubjemast and Nureddin Azizi for his constant support. And also Gary Bowersox and Guy Clutterbuck, who over the years have been fountains of knowledge on all things Afghan and Central Asian. We thank the people from Gubjemast, Kuh-i-Lal and Murghab and the government of Badakhshan who supported us during this expedition. We thank Wimon Manorotkul of Pala International for her lovely photos, and Bill Larson for making her available for this work. Finally, we thank the friendly people we met from Dushanbe to Murghab and back again. Your generosity, hospitality and smiles were the best treasures we could ever find. May all your dreams come true.

About the authors

Richard W. Hughes is one of the world’s foremost experts on ruby and sapphire. The author of several books and over 170 articles, his writings and photographs have appeared in a diverse range of publications, and he has received numerous industry awards. Co-winner of the 2004 Edward J. Gübelin Most Valuable Article Award from Gems & Gemology magazine, the following year he was awarded a Richard T. Liddicoat Journalism Award from the American Gem Society. In 2010, he received the Antonio C. Bonanno Award for Excellence in Gemology from the Accredited Gemologists Association. The Association Française de Gemmologie (AFG) in 2013 named Richard as one of the Fifty most important figures that have shaped the history of gems since antiquity. In 2016, Richard was awarded a visiting professorship at Shanghai's Tongji University. 2017 saw the publication of Richard and his wife and daughter's Ruby & Sapphire • A Gemologist's Guide, arguably the most complete book ever published on a single gem species and the culmination of nearly four decades of work in gemology. In 2018, Richard was named Photographer of the Year by the Gem-A, recognizing his photo of a jade-trading market in China, while in 2020, he was elected to the board of directors of the Accredited Gemologists Association and was appointed to the editorial review board of Gems & Gemology and The Australian Gemmologist magazine. Richard's latest book, Jade • A Gemologist's Guide, was published in 2022.

Vincent Pardieu was Lab Director at Bangkok's Asian Institute of Gemological Sciences. He then moved to Gübelin, and was later Field Gemologist at the GIA Laboratory, Bangkok. His prolific writings and research can be found at www.fieldgemology.org and at the GIA's website. Today he is an independent field gemologist, and, more than any other person, has been responsible for establishing field gemology as a vital portion of research gemology.

Guillaume Soubiraa first became interested in precious stones when he lived in Madagascar as a teenager. His interest was rekindled upon meeting the authors there in 2005. Soon he was studying gemology at AIGS in Bangkok and the rest, as they say, is history. Today he resides in Ilakaka, Madagascar, where he is involved in the trading of precious stones.

Dana Schorr of Schorr Marketing was a Santa Barbara (CA)-based gem dealer and gold trader with three decades of experience in the business. He sat on the Board of Oregon's Desert Sun Mining & Gems, which owns the Ponderosa sunstone mine, and passed away in August 2015.

Notes

Penned in September 2006, following a July 2006 visit to Tajikistan.